REPRESENTATIONS of MARIE- ANTOINETTE in 19Th

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2013 Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880 Heather Marlene Bennett University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Bennett, Heather Marlene, "Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880" (2013). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 734. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/734 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/734 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880 Abstract The traumatic legacies of the Paris Commune and its harsh suppression in 1871 had a significant impact on the identities and voter outreach efforts of each of the chief political blocs of the 1870s. The political and cultural developments of this phenomenal decade, which is frequently mislabeled as calm and stable, established the Republic's longevity and set its character. Yet the Commune's legacies have never been comprehensively examined in a way that synthesizes their political and cultural effects. This dissertation offers a compelling perspective of the 1870s through qualitative and quantitative analyses of the influence of these legacies, using sources as diverse as parliamentary debates, visual media, and scribbled sedition on city walls, to explicate the decade's most important political and cultural moments, their origins, and their impact. -

Marie Antoinette

THE DIAMOND NECKLACE AFFAIR 0. THE DIAMOND NECKLACE AFFAIR - Story Preface 1. A ROYAL CHILDHOOD 2. THE YOUNG ANTOINETTE 3. WEDDING at the PALACE of VERSAILLES 4. DEATH of LOUIS XV 5. A GROWING RESENTMENT 6. CHILDREN of MARIE ANTOINETTE 7. THE DIAMOND NECKLACE AFFAIR 8. THE FRENCH REVOLUTION 9. EXECUTION of LOUIS XVI 10. THE GUILLOTINE 11. TRIAL of MARIE ANTOINETTE 12. MARIE ANTOINETTE and the GUILLOTINE 13. Louis XVII - CHILD PRISONER 14. DNA EVIDENCE and LOUIS XVII This illustration is cropped from a larger image, published in 1856, depicting Marie Antoinette wearing a necklace. It was originally published in Le collier de la Reine ("The Queen's Necklace") by Alexandre Dumas (author of The Count of Monte Cristo and other adventure novels). The furor, against the Queen, was about a necklace. Not just any necklace. A 2,800-carat (647 brilliants) diamond necklace which the court’s jewelers (Charles Boehmer and Paul Bassenge) had fashioned and hoped the queen would purchase. Marie Antoinette, however, did not want it. Though she had previously spent a great deal of her own money on diamonds, she no longer desired to purchase extravagant jewelry. How could the queen spend money on baubles when people in the country did not have enough to eat? In fact, the queen had previously told Boehmer, the jeweler, that she did not want to buy anything more from him. Thinking he could persuade the king to buy the necklace, Boehmer convinced one of Louis’ assistants to show him the piece. Not realizing Antoinette had already rejected it, the king - who thought it would look wonderful on his wife - sent it to Antoinette. -

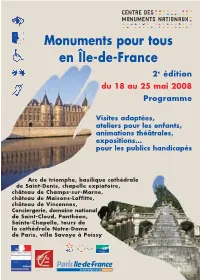

Monuments Pour Tous 2008 7/04/08 16:40 Page 1

monuments pour tous 2008 7/04/08 16:40 Page 1 Monuments pour tous en Île-de-France 2e édition du 18 au 25 mai 2008 Programme Visites adaptées, ateliers pour les enfants, animations théâtrales, expositions... pour les publics handicapés Arc de triomphe, basilique cathédrale de Saint-Denis, chapelle expiatoire, château de Champs-sur-Marne, château de Maisons-Laffitte, château de Vincennes, Conciergerie, domaine national de Saint-Cloud, Panthéon, Sainte-Chapelle, tours de la cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris, villa Savoye à Poissy monuments pour tous 2008 7/04/08 16:40 Page 2 Le Comité régional du tourisme Paris Île-de-France est un partenaire naturel de l’opération « Monuments pour tous en Île-de-France ». Depuis 2002, le CRT participe à l’amélioration de l’accueil des personnes handicapées dans les établissements touristiques et culturels franciliens, notamment en développant le label national « Tourisme & Handicap ». Cette démarche participe de la volonté de rendre Paris et sa région accessibles à tous. Démarche partenariale, la labellisation Tourisme & Handicap est menée avec les Comités départementaux du tourisme et les Associations représentatives de personnes handicapées. Démarche volontaire, elle concerne l’ensemble des prestataires touristiques et traduit un véritable esprit d’intégration. Tout en apportant une information fiable car vérifiée, homogène et objective sur l’accessibilité des sites et équipements touristiques aux personnes handicapées, le label doit en effet permettre de développer une offre touristique adaptée et intégrée à l’offre généraliste, engageant de manière pérenne les professionnels du tourisme dans une démarche d’accueil, d’accessibilité et d’information en direction des visiteurs handicapés. -

The RAMPART JOURNAL of Individualist Thought Is Published Quarterly (Maj'ch, June, September and December) by Rampart College

The Wisdom of "Hindsight" by Read Bain I On the Importance of Revisionism for Our Time by Murray N. Rothbard 3 Revisionism: A Key to Peace by llarry Elmer Barnes 8 Rising Germanophohia: The Chief Oh~~tacle to Current World War II Revisionism by Michael F. Connors 75 Revisionism and the Cold War, 1946-1~)66: Some Comments on Its Origins and Consequences by James J. Martin 91 Departments: Onthe Other Hand by Robert Lf.~Fevre 114 V01. II, No. 1 SPRING., 1966 RAMPART JOURNAL of Individualist Thought Editor .. _. __ . .__ _ __ .. __ _. Ruth Dazey Director of Publications - ---.- .. J. Dohn Lewis Published by Pine Tree Press for RAMPART COLLEGE Box 158 Larkspur, Colorado 80118 President -----------------.------------------ William J. Froh Dean . .. .__ ._ Robert LeFevre Board of Academic Advisers Robert L. Cunningham, Ph.D. Bruno Leoni, Ph.D. University of San Francisco University of Pavia San Francisco, California Turin, Italy Arthur A. Ekirch, Ph.D~ James J. Martin, Ph.D. State University of New York Rampart College Graduate School Albany, New York Larkspur, Colorado Georg. Frostenson, Ph.D. Ludwig von Mises, Ph.D. Sollentuna, Sweden New York University New York, New York J. P. Hamilius, Jr., Ph.D. Toshio Murata, M.B.A. College of Esch-sur-Alzette Luxembourg Kanto Gakuin University Yokohama, Japan F. A. Harper, Ph.D. Wm. A. Paton, Ph.D. Institute for Humane Studies University of Michigan Stanford, California Ann Arbor, Michigan F. A. von Hayek, Ph.D. Sylvester Petro, Ll.M. University of Freiburg New York University Freiburg, Germany New York, New York W. -

Kings and Courtesans: a Study of the Pictorial Representation of French Royal Mistresses

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2008 Kings and Courtesans: A Study of the Pictorial Representation of French Royal Mistresses Shandy April Lemperle The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Lemperle, Shandy April, "Kings and Courtesans: A Study of the Pictorial Representation of French Royal Mistresses" (2008). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 1258. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1258 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. KINGS AND COURTESANS: A STUDY OF THE PICTORIAL REPRESENTATION OF FRENCH ROYAL MISTRESSES By Shandy April Lemperlé B.A. The American University of Paris, Paris, France, 2006 Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Fine Arts, Art History Option The University of Montana Missoula, MT Spring 2008 Approved by: Dr. David A. Strobel, Dean Graduate School H. Rafael Chacón, Ph.D., Committee Chair Department of Art Valerie Hedquist, Ph.D., Committee Member Department of Art Ione Crummy, Ph.D., Committee Member Department of Modern and Classical Languages and Literatures Lemperlé, Shandy, M.A., Spring 2008 Art History Kings and Courtesans: A Study of the Pictorial Representation of French Royal Mistresses Chairperson: H. -

Géraldine Crahay a Thesis Submitted in Fulfilments of the Requirements For

‘ON AURAIT PENSÉ QUE LA NATURE S’ÉTAIT TROMPÉE EN LEUR DONNANT LEURS SEXES’: MASCULINE MALAISE, GENDER INDETERMINACY AND SEXUAL AMBIGUITY IN JULY MONARCHY NARRATIVES Géraldine Crahay A thesis submitted in fulfilments of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy in French Studies Bangor University, School of Modern Languages and Cultures June 2015 i TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract .................................................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................... ix Declaration and Consent ........................................................................................................... xi Introduction: Masculine Ambiguities during the July Monarchy (1830‒48) ............................ 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Theoretical Framework: Masculinities Studies and the ‘Crisis’ of Masculinity ............................. 4 Literature Overview: Masculinity in the Nineteenth Century ......................................................... 9 Differences between Masculinité and Virilité ............................................................................... 13 Masculinity during the July Monarchy ......................................................................................... 16 A Model of Masculinity: -

One and Indivisible? Federation, Federalism, and Colonialism in the Early French and Haitian Revolutions

One and Indivisible? Federation, Federalism, and Colonialism in the Early French and Haitian Revolutions MANUEL COVO abstract Histories of the French Revolution usually locate the origins of the “one and indivisible Republic” in a strictly metropolitan context. In contrast, this article argues that the French Revolution’s debates surrounding federation, federalism, and the (re)foundation of the French nation-state were interwoven with colonial and transimperial matters. Between 1776 and 1792 federalism in a French imperial context went from an element of an academic conversation among bureaucrats and economists to a matter of violent struggle in Saint- Domingue that generated new agendas in the metropole. Going beyond the binary language of union and secession, the article examines the contest over federation and federalism in Saint-Domingue between free people of color and white planters who, taking inspiration from both metropolitan and non-French experiences with federalism, sought to alter the col- ony’s relationship with the metropole while also maintaining the institution of slavery. Revo- lutionaries on both sides of the Atlantic, unsure which direction to take and without the ben- efit of hindsight, used the language of federalism to pursue rival interests despite a seemingly common vocabulary. This entangled history of conflicts, compromises, and misunderstand- ings blurred ideological delineations but decisively shaped the genesis of the French imperial republic. keywords French Revolution, Haitian Revolution, federalism, French -

Louis Philippe II, Duke of Orléans - Wikipedia

Louis Philippe II, Duke of Orléans - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louis_Philippe_II,_Duke_of_Orléans Louis Philippe II, Duke of Orléans Louis Philippe Joseph d'Orléans (13 April 1747 – 6 November 1793), commonly known as Louis Philippe Joseph Philippe, was a major French noble who supported the French Revolution. d'Orléans He was born at the Château de Saint-Cloud. He received the title of Duke of Montpensier at birth, then that of Duke of Chartres at the death of his grandfather, Louis d'Orléans, in 1752. At the death of his father, Louis Philippe d'Orléans, in 1785, he inherited the title of Duke of Orléans and also became the Premier prince du sang, title attributed to the Prince of the Blood closest to the throne after the Sons and Grandsons of France. He was addressed as Son Altesse Sérénissime (S.A.S.). In 1792, during the Revolution, he changed his name to Philippe Égalité. Louis Philippe d'Orléans was a cousin of Louis XVI and one of the wealthiest men in France. He actively supported the Revolution of 1789, and was a strong advocate for the elimination of the present absolute monarchy in favor of a constitutional monarchy. He voted for the death of King Louis XVI; however, he was himself guillotined in November 1793 during the Reign of Terror. His son Louis Philippe d'Orléans became King of the French after the July Revolution of 1830. After him, the term Orléanist came to be attached to the movement in France that favored a constitutional monarchy. Contents Early life Duke of Orléans Succession First Prince of the -

LM Findlay in the French Revolution: a History

L. M. Findlay "Maternity must forth": The Poetics and Politics of Gender in Carlyle's French Revolution In The French Revolution: A History ( 1837), Thomas Carlyle made a remarkable contribution to the history of discourse and to the legiti mation and dissemination of the idea of history qua discourse.' This work, born from the ashes of his own earlier manuscript, an irrecover able Ur-text leading us back to its equally irrecoverable 'origins' in French society at the end of the eighteenth century, represents a radical departure from the traditions of historical narrative.2 The enigmas of continuity I discontinuity conveyed so powerfully by the events of the Revolution and its aftermath are explored by Carlyle in ways that re-constitute political convulsion as the rending and repair of language as cultural fabric, or. to use terms more post-structuralist than Carlyl ean, as the process of rupture/suture in the rhetoric of temporality.3 The French Revolution, at once parodic and poetic, provisional and peremptory, announces itself as intertextual, epigraphic play, before paying tribute to the dialogic imagination in a series of dramatic and reflective periods which resonate throughout the poetry and prose of the Victorian period. In writing what Francis Jeffrey considered "undoubtedly the most poetical history the world has ever seen- and the most moral also,"4 Carlyle created an incurably reflexive idiom of astonishing modernity. And an important feature of this modernity indeed, a feature that provides a salutary reminder of the inevitably relative, historically mediated modernity of the discourse of periods earlier than our own - is the employment of countless versions of human gender to characterize and to contain the phenomenon of revolution. -

Pretty Tgirls Magazine Is a Production of the Pretty Tgirls Group and Is Intended As a Free Resource for the Transgendered Community

PrettyPretty TGirlsTGirls MagazineMagazine Featuring An Interview with Melissa Honey December 2008 Issue Pretty TGirls Magazine is a production of the Pretty TGirls Group and is intended as a free resource for the Transgendered community. Articles and advertisements may be submitted for consideration to the editor, Rachel Williston, at [email protected] . It is our hope that our magazine will increase the understanding of the TG world and better acceptance of TGirls in our society. To that end, any articles are appreciated and welcomed for review ! Pretty TGirls Magazine – December 2008 page 1 PrettyPretty TGirlsTGirls MagazineMagazine December 2008 Welcome to the December 2008 issue … Take pride and joy with being a TGirl ! Table of contents: Our Miss 2008 Cover Girls ! Our Miss December 2008 Cover Girls Cover Girl Feature – Melissa Honey Editor’s Corner – Rachel Williston Ask Sarah – Sarah Cocktails With Nicole – Nicole Morgin Dear Abby L – Abby Lauren TG Crossword – Rachel Williston In The Company Of Others – Candice O. Minky TGirl Tips – Melissa Lynn Traveling As A TGirl – Mary Jane My “Non Traditional” Makeover – Barbara M. Davidson Transgender Tunes To Try – Melissa Lynn Then and Now Photo’s Recipes by Mollie – Mollie Bell Transmission: Identity vs. Identification – Nikki S. Candidly Transgender – Brianna Austin TG Conferences and Getaways Advertisements and newsy items Our 2008 Calendar! Magazine courtesy of the Pretty TGirls Group at http://groups.yahoo.com/group/prettytgirls Pretty TGirls Magazine – December 2008 page 2 Our Miss December 2008 Cover Girls ! How about joining us? We’re a tasteful, fun group of girls and we love new friends! Just go to … http://groups.yahoo.com/group/prettytgirls Pretty TGirls Magazine – December 2008 page 3 An Interview With Melissa Honey Question: When did you first start crossdressing? Melissa: Early teens, I found a pair of nylons and thought what the heck lets try them on! I was always interested in looking at women's legs and loved the look of nylons. -

Conrad Von Hötzendorf and the “Smoking Gun”: a Biographical Examination of Responsibility and Traditions of Violence Against Civilians in the Habsburg Army 55

1914: Austria-Hungary, the Origins, and the First Year of World War I Günter Bischof, Ferdinand Karlhofer (Eds.) Samuel R. Williamson, Jr. (Guest Editor) CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES | VOLUME 23 uno press innsbruck university press Copyright © 2014 by University of New Orleans Press, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to UNO Press, University of New Orleans, LA 138, 2000 Lakeshore Drive. New Orleans, LA, 70119, USA. www.unopress.org. Printed in the United States of America Design by Allison Reu Cover photo: “In enemy position on the Piave levy” (Italy), June 18, 1918 WK1/ALB079/23142, Photo Kriegsvermessung 5, K.u.k. Kriegspressequartier, Lichtbildstelle Vienna Cover photo used with permission from the Austrian National Library – Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Vienna Published in the United States by Published and distributed in Europe University of New Orleans Press by Innsbruck University Press ISBN: 9781608010264 ISBN: 9783902936356 uno press Contemporary Austrian Studies Sponsored by the University of New Orleans and Universität Innsbruck Editors Günter Bischof, CenterAustria, University of New Orleans Ferdinand Karlhofer, Universität Innsbruck Assistant Editor Markus Habermann -

The French Revolution a Volume in the DOCUMENTARY HISTORY of WESTERN CIVILIZATION - the French Revolution

The French Revolution A volume In THE DOCUMENTARY HISTORY of WESTERN CIVILIZATION - The French Revolution Edited by PAUL H. BEIK PALGRA VE MACMILLAN ISBN 978-1-349-00528-4 ISBN 978-1-349-00526-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-00526-0 THE FRENCH REVOLUTION English translation copyright © 1970 by Paul H. Beik Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1970 978-0-333-07911-9 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without permission. First published in the United States 1970 First published in the United Kingdom by The Macmillan Press Ltd. 1971 Published by THE MACMILLAN PRESS LTD Associated companies in New York Toronto Dublin Melbourne Johannesburg and Madras SBN 333 07911 6 Contents Introduction x PART I. CROWN, PARLEMENT, AND ARISTOCRACY 1. November 19, 1787: Chretien Fran~ois de Lamoignon on Principles of the French Monarchy 1 2. April 17, 1788: Louis XVI to a Deputation from the Parlement of Paris 3 3. May 4, 1788: Repeated Remonstrances of the Parlement of Paris in Response to the King's Statement of April 17 5 4. December 12,1788: Memoir of the Princes 10 PART II. THE SURGE OF OPINION 5. January, 1789: Sieyes, What Is the Third Estate? 16 6. February, 1789: Mounier on the Estates General 37 7. March 1, 1789: Parish Cahiers of Ecommoy and Mansigne 45 8. March 14, 1789: Cahier of the Nobility of Crepy 51 9. March 26,1789: Cahier of the Clergy of Troyes 56 PART III.