B33310154.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summary 7 (2017)

Japan Border Review, No.Summary 7 (2017) Summary Austria-Hungary’s Ultimatum of 23 July 1914 Reconsidered: The Background of Vienna’s Decision-Making in the Memorandum of Friedrich von Wiesner MURAKAMI Ryo The immediate cause of the First World War was the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand at Sarajevo on 28 June 1914. Gavrilo Princip, who killed Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie, was a Serbian nationalist and a member of the Black Hand Society. The Austrian government thought that Serbia was behind the affair. In its response, Vienna sought to settle its decade-long dispute with Serbia. On 23 July 1914, the Austrian government gave an ultimatum to the Serbian government. Many researchers argue that Austria deliberately made demands that it knew Serbia could not accept. Furthermore, it is often indicated that Vienna’s ultimatum was not aimed at the Black Hand Society, but at the National Defense (in Serbian, Narodna Odbrana). Many researchers have carried out research into the diplomatic crisis (the so-called July Crisis) between the assassination at Sarajevo and the British declaration of war against Germany. Although Vienna’s declaration of war caused a chain reaction in Europe, historiographic studies still do not pay sufficient attention to either the process that led to the ultimatum, or to the Austrian justification for war against Serbia. In this article, I point out the importance of Friedrich von Wiesner, adviser on international law at the Austrian foreign ministry, during the July Crisis in Vienna. He participated by drawing up the ultimatum and he wrote the document (a memorandum) detailing charges against Serbia. -

The RAMPART JOURNAL of Individualist Thought Is Published Quarterly (Maj'ch, June, September and December) by Rampart College

The Wisdom of "Hindsight" by Read Bain I On the Importance of Revisionism for Our Time by Murray N. Rothbard 3 Revisionism: A Key to Peace by llarry Elmer Barnes 8 Rising Germanophohia: The Chief Oh~~tacle to Current World War II Revisionism by Michael F. Connors 75 Revisionism and the Cold War, 1946-1~)66: Some Comments on Its Origins and Consequences by James J. Martin 91 Departments: Onthe Other Hand by Robert Lf.~Fevre 114 V01. II, No. 1 SPRING., 1966 RAMPART JOURNAL of Individualist Thought Editor .. _. __ . .__ _ __ .. __ _. Ruth Dazey Director of Publications - ---.- .. J. Dohn Lewis Published by Pine Tree Press for RAMPART COLLEGE Box 158 Larkspur, Colorado 80118 President -----------------.------------------ William J. Froh Dean . .. .__ ._ Robert LeFevre Board of Academic Advisers Robert L. Cunningham, Ph.D. Bruno Leoni, Ph.D. University of San Francisco University of Pavia San Francisco, California Turin, Italy Arthur A. Ekirch, Ph.D~ James J. Martin, Ph.D. State University of New York Rampart College Graduate School Albany, New York Larkspur, Colorado Georg. Frostenson, Ph.D. Ludwig von Mises, Ph.D. Sollentuna, Sweden New York University New York, New York J. P. Hamilius, Jr., Ph.D. Toshio Murata, M.B.A. College of Esch-sur-Alzette Luxembourg Kanto Gakuin University Yokohama, Japan F. A. Harper, Ph.D. Wm. A. Paton, Ph.D. Institute for Humane Studies University of Michigan Stanford, California Ann Arbor, Michigan F. A. von Hayek, Ph.D. Sylvester Petro, Ll.M. University of Freiburg New York University Freiburg, Germany New York, New York W. -

Conrad Von Hötzendorf and the “Smoking Gun”: a Biographical Examination of Responsibility and Traditions of Violence Against Civilians in the Habsburg Army 55

1914: Austria-Hungary, the Origins, and the First Year of World War I Günter Bischof, Ferdinand Karlhofer (Eds.) Samuel R. Williamson, Jr. (Guest Editor) CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES | VOLUME 23 uno press innsbruck university press Copyright © 2014 by University of New Orleans Press, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to UNO Press, University of New Orleans, LA 138, 2000 Lakeshore Drive. New Orleans, LA, 70119, USA. www.unopress.org. Printed in the United States of America Design by Allison Reu Cover photo: “In enemy position on the Piave levy” (Italy), June 18, 1918 WK1/ALB079/23142, Photo Kriegsvermessung 5, K.u.k. Kriegspressequartier, Lichtbildstelle Vienna Cover photo used with permission from the Austrian National Library – Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Vienna Published in the United States by Published and distributed in Europe University of New Orleans Press by Innsbruck University Press ISBN: 9781608010264 ISBN: 9783902936356 uno press Contemporary Austrian Studies Sponsored by the University of New Orleans and Universität Innsbruck Editors Günter Bischof, CenterAustria, University of New Orleans Ferdinand Karlhofer, Universität Innsbruck Assistant Editor Markus Habermann -

Grandi Battaglie

LLAA BBAATTTTAAGGLLIIAA DDII LLEEOOPPOOLLII 23 agosto – 11 settembre 1914 Dalla Sesta alla Decima Parte Premessa La città di Leopoli si trova oggi in Ucraina (ex-regione dell’URSS ed oggi Stato indipendente) sotto il nome di L’viv. Conta circa 800 mila abitanti. Fondata nel 1256 dal Principe Daniele Romanov, ricevette in dote il nome di Lev (toponimo derivante dal nome del figlio). Teatro di vari scontri, zona contesa dalle potenze continentali, fece parte dell’Impero Austriaco e quindi dell’Unione Sovietica. Vanta un centro storico di tutto rispetto (è patrimonio dell’umanità dell’UNESCO) con edifici di stile composito e fra lo stile rinascimentale e il barocco. Una panoramica di L’viv (l’antica Leopoli) 1 Il centro di L’viv Il Fronte Orientale nel 1914 2 L’Ucraina, oggi Dallo spaccato si deduce che L’viv (Leopoli) si trova nella parte occidentale dell’Ucraina, dove si svolse la celebre Battaglia dell’agosto-settembre 1914 3 Sesta Parte LA STRATEGIA D’ATTACCO AUSTROUNGARICA L’Austria-Ungheria e la Germania hanno stipulato un’alleanza solida, in cui l’Italia rappresenta se non un terzo incomodo nelle “calde nozze”, certamente un elemento infido da tenere sotto stretto controllo, soprattutto per i precedenti non remoti delle Guerre d’Indipendenza, ma anche per le rivendicazioni concernenti le regioni italiane irredente. Della dissonanza italiana all’interno della Triplice sono consapevoli sia la Germania, sia l’Austria-Ungheria. Guglielmo II non manca di lanciare strali polemici contro l’Italia, che aveva aderito all’Alleanza per sfuggire allo spettro dell’isolamento internazionale, cui l’avevano condannata una politica ambigua e le mire espansionistiche che si erano manifestate negli appetiti “colonialistici” in terra d’Africa. -

Count Albert Apponyi;

Author Title B iMfiprint. 16—47372-2 GPO Count Albert Apponyi The so-called Angel of Peace, and what he stands for in Hungary. A few pen pictures by Bjornstjerne Bjornson and others. aJHGAK^^^ Property of * 'Whatsoever ye would that men should do unto you, do ye even so to them." 6 Copy- 39 6 M 7 AUG 1953 111 r\ -^^^ s- PREFACE "Whatsoever ye would that men should do unto you, do ye even so to them." To our American Fellow-Citizens: to a few facts This booklet is issued for the purpose of presenting you you how little abovtt the record of Count Apponyi Avith a view to showing before the his conduct at home in his own country, entitles him to pose them." The world as an "angel of peace." "By their fruits ye shall know which is re- outrages against civilization, such as the Csernova massacre, in Hungary of printed in this booklet, are a part of a governmental system time of this mas- which the Count is one of the leading exponents. At the so-called Coalition sacre, Count Apponyi was minister of education in the their Cabinet. In this booklet we have cited from the works of non-Slavs witnesses to condemnation of Apponyi and all that he stands for. As our non-Magyar the truth about the persecutions and outrages to which the themselves) are people of Hungary (and in many instances the Magyars Bjornson, subjected, we refer you to the statements of the late Bjornstjerne Scot; to the grand old man of Norway; to those of R. -

Did Pope Pius XII Help the Jews?

Did Pope Pius XII Help the Jews? by Margherita Marchione 1 Contents Part I - Overview………………………3 Did Pius XII help Jews? Part II - Yad Vashem …………………6 Does Pius XII deserve this honor? Part III - Testimonials…………………11 Is Jewish testimony available? Part IV - Four Hundred Visas……….16 Did Pius XII obtain these visas? Part V - Documentation………………19 When will vilification of Pius XII end? Part VI - World Press………………...23 How has the press responded? Part VII - Jewish Survivors…………...31 Have Survivors acknowledged help? Part VIII - Bombing of Rome…………34 Did the Pope help stop bombing? Part IX - Nazis and Jews Speak Out…37 Did Nazis and Jews speak out? Part X - Conclusion…………………....42 Should Yad Vashem honor Pius XII? 2 Part I - Overview Did Pius XII help Jews? In his book Adolf Hitler (Doubleday, 1976, Volume II, p. 865), John Toland wrote: "The Church, under the Pope's guidance [Pius XII], had (by June, 1943) already saved the lives of more Jews than all other churches, religious institutions and rescue organizations combined, and was presently hiding thousands of Jews in monasteries, convents and Vatican City itself. …The British and Americans, despite lofty pronouncements, had not only avoided taking any meaningful action but gave sanctuary to few persecuted Jews." It is historically correct to say that Pope Pius XII, through his bishops, nuncios, and local priests, mobilized Catholics to assist Jews, Allied soldiers, and prisoners of war. There is a considerable body of scholarly opinion that is convinced Pius XII is responsible for having saved 500,000 to 800,000 Jewish lives. -

REPRESENTATIONS of MARIE- ANTOINETTE in 19Th

L’AUGUSTE AUTRICHIENNE: REPRESENTATIONS OF MARIE- ANTOINETTE IN 19th CENTURY FRENCH LITERATURE AND HISTORY --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- by KALYN ROCHELLE BALDRIDGE Dr. Carol Lazzaro-Weis, Dissertation Superviser MAY 2016 APPROVAL PAGE The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled L’AUGUSTE AUTRICHIENNE: REPRESENTATIONS OF MARIE-ANTOINETTE IN 19th CENTURY FRENCH LITERATURE AND HISTORY presented by Kalyn Rochelle Baldridge, a candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor Carol Lazzaro-Weis Professor Ilyana Karthas Professor Valerie Kaussen Professor Megan Moore Professor Daniel Sipe ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first of all like to acknowledge the Department of Romance Languages at the University of Missouri for having supported me throughout my dissertation writing process, allowing me to spend time in France, and welcoming me back to the campus for my final year of study. Secondly, I would like to thank the members of my committee, Dr. Valerie Kaussen, Dr. Megan Moore and Dr. Daniel Sipe, for taking the time to read my research and offer their welcome suggestions and insight. I would especially like to thank Dr. Ilyana Karthas, from the Department of History, for having spent many hours reading earlier drafts of my chapters and providing me with valuable feedback which spurred me on to new discoveries. I am most grateful to my dissertation superviser, Dr. Carol Lazzaro-Weis. -

Abbreviations

Abbreviations Austria, Austria, Stenographische Sitzungs-Protokolle der Protokolle Delegation des Reichsrathes: Neunundvierzigste Session: Budapest 1914 Berchtold Diary 'Memoiren des Grafen Leopold Berchtold' Conrad Franz Conrad von Hotzendorf, Aus meiner Dienstzeit Documents Serbie Documents sur la politique exterieure du Royaume de Serb ie, 1903-1914 [Documenti 0 spoljnoj politici Kraljevine Srbije, 1903-1914} GP Die grosse Politik der europiiischen Kabinette, 1871- 1914 HHStA Haus-, Hof- und Staatsarchiv, Vienna JMH Journal of Modem History KA Kriegsarchiv, Vienna KD Outbreak of the World War: German Documents Collected by Karl Kautsky (Kautsky Documents) KM Pras Kriegsminsterium Prasidial Series MKFF Militarkanzlei des Generalinspektors der gesamten bewaffneten Macht (Franz Ferdinand), Kriegsarchiv, Vienna MKSM Militarkanzlei Seiner Majestat des Kaisers (Franz Joseph), Kriegsarchiv, Vienna MOS Mitteilungen des Osterreichischen Staatsarchivs NFF Nachlass Franz Ferdinand, Haus-, Hof- und Staatsarchiv, Vienna PA Politisches Archiv, Haus-, Hof- und Staatsarchiv, Vienna ~UA Osterreich-Ungarns Aussenpolitik von der Bosnischen Krise 1908 bis zum Kriegsausbruch 1914 VA Verwaltungsarchiv, Vienna 217 Notes and References l. AUSTRIA-HUNGARY AND THE INTERNATIONAL SYSTEM: GREAT POWER OR DOOMED ANACHRONISM? I. The quotes are from Joachim Remak, 'The Healthy Invalid: How Doomed the Habsburg Monarchy?', Journal of Modern History [hereafter JMHJ, XLI Uune 1969) 131-2. On the history of the monarchy, these works remain standard: A. J. May, The Hapsburg Monarchy, 1867-1914 (Cam bridge, Mass., 1951); A. J. P. Taylor, The Habsburg Monarchy, 1809-1918 (London, 1948); C. A. Macartney, The Habsburg Empire, 1790-1918 (London, 1968); Robert A. Kann, A History of the Habsburg Empire, 1526- 1918 (Berkeley, Calif., 1974); J6zsef Galantai, Die Osterreichisch-Ungarische Monarchie und der Weltkrieg (Budapest, 1979); and two recent surveys, John W. -

Leering at Vienna the Slovaks, Franz Ferdinand, and the Archduke’S Reform Plans

Kristián Mennen LEERING AT VIENNA THE SLOVAKS, FRANZ FERDINAND, AND THE ARCHDUKE’S REFORM PLANS Although it is relatively uncommon in modern historiography to consider personal sympathies, the čase of the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand forms a notable exception. Discussions as to whether Franz Ferdinand “hated” or “disliked” the Magyars, or whether he “liked” the Germans or the Czechs, dominated reflections on him by both contemporaries and later historians. The question of his “likes” and “dislikes” becomes more understandable if one considers that his sympathies can not be measured by his political actions for the simple reason that he never went through with these actions. Alexandru Vaida-Voevoďs assertion that “He had clear sympa- thies for the Slovaks, that good peasant people”1 is certainly informative. It does not, however, offer any clues to practical contacts or specific plans in the political field. Until now there has been no cohesive study of Franz Ferdinanďs contacts with the Slovaks. This can be explained partly by the fact that for his many biographers, his contacts with the Slovaks were seen to be of little relevance. As I will show below, both the contacts themselves and the source materials concerning them are relative- ly limited. Centring on the politician Milan Hodža, Slovák historiography has not tended to locate his correspondence with Franz Ferdinand in the context of the latter’s political views. In her 1983 article, “Milan Hodža and the Politics of Power, 1907-1914 ”,2 the Slovák historian Susan Mikula examines Hodža’s plans and moti- vations, and links these to his ensuing contacts with Franz Ferdinand. -

Explaining the Blank Check

International Interactions, 35:106–127, 2009 Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 0305-0629 DOI: 10.1080/03050620902743960 GINI0305-06291547-7444International Interactions,InteractionsAfter Vol. 35, No. 1, Feb 2009: pp. 0–0 Sarajevo: Explaining the Blank Check AfterF. C. ZagareSarajevo: Explaining the Blank Check FRANK C. ZAGARE Department of Political Science, University at Buffalo, State University of New York, Buffalo, New York, USA This paper uses an incomplete information game model to describe and explain the so-called blank check issued to Austria by Germany in early July 1914. It asks why Germany would cede control of an important aspect of its foreign policy to another lesser power. The derived explanation is consistent not only with the actual beliefs of German and Austrian leaders but also with an equilibrium predic- tion of the game model. The issue of whether unconditional German support of Austria constituted either a necessary or a sufficient condi- tion for the outbreak of major power war the next month is also addressed. KEYWORDS World War I, alliances, crisis, deterrence, game theory “An explanation is. the assurance that an outcome must be the way it is because of antecedent conditions. This is precisely what an equilibrium provides.” William Riker (1990) Downloaded By: [Zagare, Frank] At: 15:45 11 March 2009 There are few who would take exception to George Kennan’s (1979, p. 3) characterization of World War I as “the great seminal catastrophe” of the 20th century. Yet there seems to be little else about the Great War that is commonly accepted. Almost one hundred years after the war’s outbreak, there remains a stunning lack of consensus among historians and political scientists about what brought it about, which country was most responsible for its occurrence, whether it was intended, and whether it was inevitable. -

Istvan Tisza and the Rumanian National Party, 1910-1914

The Nationality Problem in Hungary: Istvan Tisza and the Rumanian National Party, 1910-1914 Keith Hitchins University of Illinois Beginning in the last decade of the nineteenth century down to the outbreak of the First World War relations between the Hungarian government and its large Rumanian minority1 steadily deteriorated. On the one side, the leaders of the principal Magyar political parties and factions intensified their efforts to transform multinational Hun- gary into a Magyar national state. On the other side, Rumanian leaders tried to shore up their defenses by strengthening existing autonomous national institutions such as the Greek Catholic and Orthodox churches and schools and by creating new ones such as banks and agricultural cooperatives. The most perceptible result of this struggle was the continued isolation of the Rumanian population as a whole from the political and social life of Greater Hungary. Rumanian leaders had set forth their position at a series of confer- ences of the National Party, which had dominated Rumanian political activity since its founding in 1881. At the heart of successive formu- lations of a national program lay unbending opposition to the new, centralized Hungarian state created by the Austro-Hungarian Com- promise of 1867 along with the demand for wide-ranging political, cultural, and economic autonomy. Characteristic of the Magyar nationalist position in these years was the policy pursued by ~ezso"Banffy, Prime Minister from 1895 to 1899. A consistent champion of the "unitary Magyar national state" and of the forcible assimilation of the minorities, he rejected the whole idea of national equality as merely the first step in the dissolu- tion of historical Hungary. -

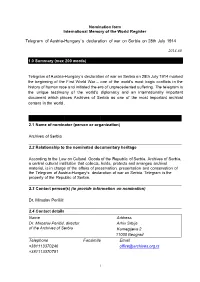

Nomination Form International Memory of the World Register

Nomination form International Memory of the World Register Telegram of Austria-Hungary`s declaration of war on Serbia on 28th July 1914 2014-60 1.0 Summary (max 200 words) Telegram of A ustria-Hungary`s declaration of war on Serbia on 28th July 1914 marked the beginning of the First World War – one of the world's most tragic conflicts i n the history of human race and initiated the era of unprecedented suffering. The telegram is the unique testimony of the world's diplomacy and an internationally important document which places Archives of Serbia as one of the most important archival centers in the world . 2.0 Nominator 2.1 Name of nominator (person or organization) Archives of Serbia 2.2 Relationship to the nominated documentary heritage According to the Law on Cultural Goods of the Republic of Serbia, Archives of Serbia, a central cultural institution that collects, holds, protects and arranges archival material, is in charge of the affairs of preservation, presentation and conservation of the Telegram of Austria-Hungary`s declaration of war on Serbia. Telegram is the property of the Republic of Serbia. 2.3 Contact person(s) (to provide information on nomination) Dr. Miroslav Perišić 2.4 Contact details Name Address Dr. Miroslav Perišić, director Arhiv Srbije of the Archives of Serbia Karnegijeva 2 11000 Beograd Telephone Facsimile Email +381113370246 [email protected] +381113370781 1 3.0 Identity and description of the documentary heritage 3.1 Name and identification details of the items being nominated If inscribed, the exact title and institution(s) to appear on the certificate should be given Telegram of Austria-Hungary`s declaration of war on Serbia, sent by Foreign Affairs Minister of Austria-Hungary, Count Leopold Berchtold on July 28, 1914.