Book Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summary 7 (2017)

Japan Border Review, No.Summary 7 (2017) Summary Austria-Hungary’s Ultimatum of 23 July 1914 Reconsidered: The Background of Vienna’s Decision-Making in the Memorandum of Friedrich von Wiesner MURAKAMI Ryo The immediate cause of the First World War was the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand at Sarajevo on 28 June 1914. Gavrilo Princip, who killed Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie, was a Serbian nationalist and a member of the Black Hand Society. The Austrian government thought that Serbia was behind the affair. In its response, Vienna sought to settle its decade-long dispute with Serbia. On 23 July 1914, the Austrian government gave an ultimatum to the Serbian government. Many researchers argue that Austria deliberately made demands that it knew Serbia could not accept. Furthermore, it is often indicated that Vienna’s ultimatum was not aimed at the Black Hand Society, but at the National Defense (in Serbian, Narodna Odbrana). Many researchers have carried out research into the diplomatic crisis (the so-called July Crisis) between the assassination at Sarajevo and the British declaration of war against Germany. Although Vienna’s declaration of war caused a chain reaction in Europe, historiographic studies still do not pay sufficient attention to either the process that led to the ultimatum, or to the Austrian justification for war against Serbia. In this article, I point out the importance of Friedrich von Wiesner, adviser on international law at the Austrian foreign ministry, during the July Crisis in Vienna. He participated by drawing up the ultimatum and he wrote the document (a memorandum) detailing charges against Serbia. -

Conrad Von Hötzendorf and the “Smoking Gun”: a Biographical Examination of Responsibility and Traditions of Violence Against Civilians in the Habsburg Army 55

1914: Austria-Hungary, the Origins, and the First Year of World War I Günter Bischof, Ferdinand Karlhofer (Eds.) Samuel R. Williamson, Jr. (Guest Editor) CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES | VOLUME 23 uno press innsbruck university press Copyright © 2014 by University of New Orleans Press, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to UNO Press, University of New Orleans, LA 138, 2000 Lakeshore Drive. New Orleans, LA, 70119, USA. www.unopress.org. Printed in the United States of America Design by Allison Reu Cover photo: “In enemy position on the Piave levy” (Italy), June 18, 1918 WK1/ALB079/23142, Photo Kriegsvermessung 5, K.u.k. Kriegspressequartier, Lichtbildstelle Vienna Cover photo used with permission from the Austrian National Library – Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Vienna Published in the United States by Published and distributed in Europe University of New Orleans Press by Innsbruck University Press ISBN: 9781608010264 ISBN: 9783902936356 uno press Contemporary Austrian Studies Sponsored by the University of New Orleans and Universität Innsbruck Editors Günter Bischof, CenterAustria, University of New Orleans Ferdinand Karlhofer, Universität Innsbruck Assistant Editor Markus Habermann -

B33310154.Pdf

L 9fc 31 PISL-14 COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA SOM S-6S DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION STATE LIBRARY HARRIS BURH In case of failure to return the books the borrower agrees to pay the original price of the same, or to replace them with other copies. The last borrower is held responsible for any mutilation. Return this book on or before the last date stamped below. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/july1400emil JULY '14 By EMIL LUDWIG Author of "Goethe," "WilheSm HoherjzolJe™," etc. Translated from the German by C. A. MACARTNEY " <5A man need not have been a "Bismarck to prevent this most idiotic of all wars." BALLIN With 16 Illustrations NEW YORK : LONDON G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS JULY '14 ^> Copyright, 1929 by G. P. Putnam's Sons First Printing, Nov., 1929 Second " Nov., 1929 Third " Jan., 1930 e in the United States of America To Our Sons—In Warning 234821 The thanks of the Translator and the Publishers are due to Dr. J. F. Muirhead for reading the translation both in typescript and in proof and for making very many valuable suggestions. FOREWORD THE war-guilt belongs to all Europe; re- searches in every country have proved this. Germany's exclusive guilt or Germany's innocence are fairy-tales for children on both sides of the Rhine. What country wanted the war? Let us put a different question: What circles in every country wanted, facilitated, or began the war? If, instead of a horizontal section through Europe, we take a vertical section through society, we find that the sum of guilt was in the Cabinets, the sum of innocence in the streets of Europe. -

Grandi Battaglie

LLAA BBAATTTTAAGGLLIIAA DDII LLEEOOPPOOLLII 23 agosto – 11 settembre 1914 Dalla Sesta alla Decima Parte Premessa La città di Leopoli si trova oggi in Ucraina (ex-regione dell’URSS ed oggi Stato indipendente) sotto il nome di L’viv. Conta circa 800 mila abitanti. Fondata nel 1256 dal Principe Daniele Romanov, ricevette in dote il nome di Lev (toponimo derivante dal nome del figlio). Teatro di vari scontri, zona contesa dalle potenze continentali, fece parte dell’Impero Austriaco e quindi dell’Unione Sovietica. Vanta un centro storico di tutto rispetto (è patrimonio dell’umanità dell’UNESCO) con edifici di stile composito e fra lo stile rinascimentale e il barocco. Una panoramica di L’viv (l’antica Leopoli) 1 Il centro di L’viv Il Fronte Orientale nel 1914 2 L’Ucraina, oggi Dallo spaccato si deduce che L’viv (Leopoli) si trova nella parte occidentale dell’Ucraina, dove si svolse la celebre Battaglia dell’agosto-settembre 1914 3 Sesta Parte LA STRATEGIA D’ATTACCO AUSTROUNGARICA L’Austria-Ungheria e la Germania hanno stipulato un’alleanza solida, in cui l’Italia rappresenta se non un terzo incomodo nelle “calde nozze”, certamente un elemento infido da tenere sotto stretto controllo, soprattutto per i precedenti non remoti delle Guerre d’Indipendenza, ma anche per le rivendicazioni concernenti le regioni italiane irredente. Della dissonanza italiana all’interno della Triplice sono consapevoli sia la Germania, sia l’Austria-Ungheria. Guglielmo II non manca di lanciare strali polemici contro l’Italia, che aveva aderito all’Alleanza per sfuggire allo spettro dell’isolamento internazionale, cui l’avevano condannata una politica ambigua e le mire espansionistiche che si erano manifestate negli appetiti “colonialistici” in terra d’Africa. -

Abbreviations

Abbreviations Austria, Austria, Stenographische Sitzungs-Protokolle der Protokolle Delegation des Reichsrathes: Neunundvierzigste Session: Budapest 1914 Berchtold Diary 'Memoiren des Grafen Leopold Berchtold' Conrad Franz Conrad von Hotzendorf, Aus meiner Dienstzeit Documents Serbie Documents sur la politique exterieure du Royaume de Serb ie, 1903-1914 [Documenti 0 spoljnoj politici Kraljevine Srbije, 1903-1914} GP Die grosse Politik der europiiischen Kabinette, 1871- 1914 HHStA Haus-, Hof- und Staatsarchiv, Vienna JMH Journal of Modem History KA Kriegsarchiv, Vienna KD Outbreak of the World War: German Documents Collected by Karl Kautsky (Kautsky Documents) KM Pras Kriegsminsterium Prasidial Series MKFF Militarkanzlei des Generalinspektors der gesamten bewaffneten Macht (Franz Ferdinand), Kriegsarchiv, Vienna MKSM Militarkanzlei Seiner Majestat des Kaisers (Franz Joseph), Kriegsarchiv, Vienna MOS Mitteilungen des Osterreichischen Staatsarchivs NFF Nachlass Franz Ferdinand, Haus-, Hof- und Staatsarchiv, Vienna PA Politisches Archiv, Haus-, Hof- und Staatsarchiv, Vienna ~UA Osterreich-Ungarns Aussenpolitik von der Bosnischen Krise 1908 bis zum Kriegsausbruch 1914 VA Verwaltungsarchiv, Vienna 217 Notes and References l. AUSTRIA-HUNGARY AND THE INTERNATIONAL SYSTEM: GREAT POWER OR DOOMED ANACHRONISM? I. The quotes are from Joachim Remak, 'The Healthy Invalid: How Doomed the Habsburg Monarchy?', Journal of Modern History [hereafter JMHJ, XLI Uune 1969) 131-2. On the history of the monarchy, these works remain standard: A. J. May, The Hapsburg Monarchy, 1867-1914 (Cam bridge, Mass., 1951); A. J. P. Taylor, The Habsburg Monarchy, 1809-1918 (London, 1948); C. A. Macartney, The Habsburg Empire, 1790-1918 (London, 1968); Robert A. Kann, A History of the Habsburg Empire, 1526- 1918 (Berkeley, Calif., 1974); J6zsef Galantai, Die Osterreichisch-Ungarische Monarchie und der Weltkrieg (Budapest, 1979); and two recent surveys, John W. -

Leering at Vienna the Slovaks, Franz Ferdinand, and the Archduke’S Reform Plans

Kristián Mennen LEERING AT VIENNA THE SLOVAKS, FRANZ FERDINAND, AND THE ARCHDUKE’S REFORM PLANS Although it is relatively uncommon in modern historiography to consider personal sympathies, the čase of the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand forms a notable exception. Discussions as to whether Franz Ferdinand “hated” or “disliked” the Magyars, or whether he “liked” the Germans or the Czechs, dominated reflections on him by both contemporaries and later historians. The question of his “likes” and “dislikes” becomes more understandable if one considers that his sympathies can not be measured by his political actions for the simple reason that he never went through with these actions. Alexandru Vaida-Voevoďs assertion that “He had clear sympa- thies for the Slovaks, that good peasant people”1 is certainly informative. It does not, however, offer any clues to practical contacts or specific plans in the political field. Until now there has been no cohesive study of Franz Ferdinanďs contacts with the Slovaks. This can be explained partly by the fact that for his many biographers, his contacts with the Slovaks were seen to be of little relevance. As I will show below, both the contacts themselves and the source materials concerning them are relative- ly limited. Centring on the politician Milan Hodža, Slovák historiography has not tended to locate his correspondence with Franz Ferdinand in the context of the latter’s political views. In her 1983 article, “Milan Hodža and the Politics of Power, 1907-1914 ”,2 the Slovák historian Susan Mikula examines Hodža’s plans and moti- vations, and links these to his ensuing contacts with Franz Ferdinand. -

Explaining the Blank Check

International Interactions, 35:106–127, 2009 Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 0305-0629 DOI: 10.1080/03050620902743960 GINI0305-06291547-7444International Interactions,InteractionsAfter Vol. 35, No. 1, Feb 2009: pp. 0–0 Sarajevo: Explaining the Blank Check AfterF. C. ZagareSarajevo: Explaining the Blank Check FRANK C. ZAGARE Department of Political Science, University at Buffalo, State University of New York, Buffalo, New York, USA This paper uses an incomplete information game model to describe and explain the so-called blank check issued to Austria by Germany in early July 1914. It asks why Germany would cede control of an important aspect of its foreign policy to another lesser power. The derived explanation is consistent not only with the actual beliefs of German and Austrian leaders but also with an equilibrium predic- tion of the game model. The issue of whether unconditional German support of Austria constituted either a necessary or a sufficient condi- tion for the outbreak of major power war the next month is also addressed. KEYWORDS World War I, alliances, crisis, deterrence, game theory “An explanation is. the assurance that an outcome must be the way it is because of antecedent conditions. This is precisely what an equilibrium provides.” William Riker (1990) Downloaded By: [Zagare, Frank] At: 15:45 11 March 2009 There are few who would take exception to George Kennan’s (1979, p. 3) characterization of World War I as “the great seminal catastrophe” of the 20th century. Yet there seems to be little else about the Great War that is commonly accepted. Almost one hundred years after the war’s outbreak, there remains a stunning lack of consensus among historians and political scientists about what brought it about, which country was most responsible for its occurrence, whether it was intended, and whether it was inevitable. -

Istvan Tisza and the Rumanian National Party, 1910-1914

The Nationality Problem in Hungary: Istvan Tisza and the Rumanian National Party, 1910-1914 Keith Hitchins University of Illinois Beginning in the last decade of the nineteenth century down to the outbreak of the First World War relations between the Hungarian government and its large Rumanian minority1 steadily deteriorated. On the one side, the leaders of the principal Magyar political parties and factions intensified their efforts to transform multinational Hun- gary into a Magyar national state. On the other side, Rumanian leaders tried to shore up their defenses by strengthening existing autonomous national institutions such as the Greek Catholic and Orthodox churches and schools and by creating new ones such as banks and agricultural cooperatives. The most perceptible result of this struggle was the continued isolation of the Rumanian population as a whole from the political and social life of Greater Hungary. Rumanian leaders had set forth their position at a series of confer- ences of the National Party, which had dominated Rumanian political activity since its founding in 1881. At the heart of successive formu- lations of a national program lay unbending opposition to the new, centralized Hungarian state created by the Austro-Hungarian Com- promise of 1867 along with the demand for wide-ranging political, cultural, and economic autonomy. Characteristic of the Magyar nationalist position in these years was the policy pursued by ~ezso"Banffy, Prime Minister from 1895 to 1899. A consistent champion of the "unitary Magyar national state" and of the forcible assimilation of the minorities, he rejected the whole idea of national equality as merely the first step in the dissolu- tion of historical Hungary. -

Nomination Form International Memory of the World Register

Nomination form International Memory of the World Register Telegram of Austria-Hungary`s declaration of war on Serbia on 28th July 1914 2014-60 1.0 Summary (max 200 words) Telegram of A ustria-Hungary`s declaration of war on Serbia on 28th July 1914 marked the beginning of the First World War – one of the world's most tragic conflicts i n the history of human race and initiated the era of unprecedented suffering. The telegram is the unique testimony of the world's diplomacy and an internationally important document which places Archives of Serbia as one of the most important archival centers in the world . 2.0 Nominator 2.1 Name of nominator (person or organization) Archives of Serbia 2.2 Relationship to the nominated documentary heritage According to the Law on Cultural Goods of the Republic of Serbia, Archives of Serbia, a central cultural institution that collects, holds, protects and arranges archival material, is in charge of the affairs of preservation, presentation and conservation of the Telegram of Austria-Hungary`s declaration of war on Serbia. Telegram is the property of the Republic of Serbia. 2.3 Contact person(s) (to provide information on nomination) Dr. Miroslav Perišić 2.4 Contact details Name Address Dr. Miroslav Perišić, director Arhiv Srbije of the Archives of Serbia Karnegijeva 2 11000 Beograd Telephone Facsimile Email +381113370246 [email protected] +381113370781 1 3.0 Identity and description of the documentary heritage 3.1 Name and identification details of the items being nominated If inscribed, the exact title and institution(s) to appear on the certificate should be given Telegram of Austria-Hungary`s declaration of war on Serbia, sent by Foreign Affairs Minister of Austria-Hungary, Count Leopold Berchtold on July 28, 1914. -

The Austro-Hungarian Empire and Its Political Allies in the Polish Kingdom 1914–1918

J ERZY G AUL The Austro-Hungarian Empire and its political allies in the Polish Kingdom 1914–1918 The Austro-Hungarian declaration of war against Serbia on July 28, 1914 caused very important but unintentional consequences. The civil und military authorities of the Empire expected the con- flict to be substantially successful and to increase their influence in the Balkan area. The situation changed radically at the beginning of August 1914 with the transformation of the local conflict into a great war in which all the European powers were involved. In the years 1914–1915 the fight on the Eastern front against the Russian armies took place mostly on the soil of Galicia and within the Polish Kingdom. This brought the Polish Cause into the limelight. The Polish Cause was determined in 1881 by the alliance of the Three Emperors, which guaranteed Austro-Hungary, Russia, and Ger- many the continuous possession of the Polish territories, which had been captured in the partitions of Poland between 1772–1795. In the years 1915–1918 the occupation of the Polish Kingdom’s southern territories by the Austro-Hungarian troops and the creation of the General Military Gov- ernorship in Poland forced the political elite of the Empire to rethink Poland’s future. This occurred because of the great pressure exercised by the representatives of the Polish nation with their politi- cal, economical, and cultural demands. It was necessary to create a political program to realize those demands and to identify its opponents as well as to find political partners within Polish society. The purpose of this paper is to examine the political situation in the Polish Kingdom after the outbreak of the First World War, the solution to the Polish Cause proposed by the authorities of the Habsburg monarchy, and to look at its potential allies. -

Burián Von Rajecz, István, Graf | International Encyclopedia of The

Version 1.0 | Last updated 08 January 2017 Burián von Rajecz, István, Graf By Marvin Benjamin Fried Burián von Rajecz, István Stephan Diplomat, Politician Born 16 January 1851 in Stampfen/Stomfa, Austrian Empire Died 20 October 1922 in Vienna, Republic of Austria István Burián was a leading Austro-Hungarian career diplomat and politician, rising to become the Monarchy’s longest-serving foreign minister during the First World War. Burián’s wartime policies included trying to pacify neighboring neutrals and expanding Austro- Hungarian power and influence, particularly in the Balkans and Poland. Table of Contents 1 Early Life 2 Diplomatic Career 3 Foreign Minister During World War I 4 Dismissal and Return 5 Conclusion Selected Bibliography Citation 1. Early Life A member of the Hungarian middle nobility, István Burián (1851-1922) was born in Stampfen/Stomfa, located northwest of Pressburg/Pozsony, in the Austrian Empire. Burián’s formative years were shaped by the instability of the 1848 revolutions and the Monarchy’s subsequent reorganization into the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1867, giving him an unusual mix of liberal and conservative Protestant values. Bu2ri.n vDoni pRaljoecmz, Isatvtni, cG raCf -a 1r91e4e-1r918-Online 1/4 2. Diplomatic Career Burián was ambitious and committed to his diplomatic career, despite a reputation for being a withdrawn and aloof intellectual. He prized the Magyar minority position within the Hungarian half of the Monarchy, while still being fiercely loyal to the imperial Crown. Trained as a diplomat and possessing a keen interest in Eastern Europe, Burián never veered from the region of his specialization. After several minor postings, his first major role was consul general in Moscow, then consul general in Sofia (1887-1895). -

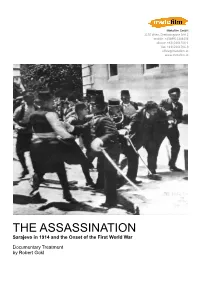

THE ASSASSINATION Sarajevo in 1914 and the Onset of the First World War

Metafilm GmbH 1150 Wien, Dreihausgasse 9/H.2 mobile: +4369911144436 phone: +4312361706-1 fax: +4312361706-9 [email protected] www.metafilm.at THE ASSASSINATION Sarajevo in 1914 and the Onset of the First World War Documentary Treatment by Robert Gokl 2 It was to be a military walk in the park, a rapid victory, and a confirmation of superiority: "Serbien muss sterbien - Serbia must die!" Austria-Hungary finally declared the war that, for many years, the European powers had been waiting and arming for, with no idea of the consequences the war would bring. It resulted in the Great War, the end of old European structures, the first catastrophe of the twentieth century, the beginning of a new era - and the foundation for a far more terrible war just two decades later. "THE ASSASSINATION - SARAJEVO IN 1914 AND THE ONSET OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR" uses elaborate re-enactments, fascinating CGI and previously unseen archive footage to examine how the assassination in Sarajevo in 1914 came about and how Austria-Hungary used the death of the heir to the throne, Franz Ferdinand, to start a war against Serbia. The film investigates how this regional conflict caused the Central Powers and the Triple Entente to enter the First World War - at the time, the biggest war in history with 17 million soldiers and civilians killed and more than 20 million injured. 3 The Countdown Austria-Hungary had annexed Bosnia- Herzegovina just a few years prior to the fateful assassination, a pyrrhic victory for the multicultural empire. Battles for power and influence in the Balkans had increased since 1903, when the Serbian king Alexander Obrenovic was assassinated.