Serbia, Sarajevo and the Outbreak of the First World War | LSEE Blog

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wwi 1914 - 1918

ABSTRACT This booklet will introduce you to the key events before and during the First World War. Taking place from 1914 – 1918, millions of people across the world lost their lives in what was supposed to be ‘the war to end all wars’. Fighting on this scale had never been seen before. The work in this booklet will help you understand why such a horrific conflict begun. Ms Marsh WWI 1914 - 1918 Year 8 History Why did the First World War begin? L.O: I can explain the causes of the First World War. 1. In what year did the war begin? 2. In what year did the war end? 3. How many years did it last? (Do now answers at end of booklet) The First World War begun in August 1914. It took the world by surprise, and seemed to happen overnight. In reality, tension between countries in Europe had been increasing for some years before. The final event that triggered war, the assassination of a young heir to the Austria – Hungary throne, demonstrates how this tension had been building. Europe in the early 20th century was a place where newly formed countries such as Italy started to challenge the dominance of countries with empires. An empire is when one country rules over others around the world. Some countries began to demand their independence and did not want to be ruled by an empire. The map opposite shows just how vast the empires of Europe were; Britain had control of Australia, New Zealand, Canada, East and South Africa and India. -

Summary 7 (2017)

Japan Border Review, No.Summary 7 (2017) Summary Austria-Hungary’s Ultimatum of 23 July 1914 Reconsidered: The Background of Vienna’s Decision-Making in the Memorandum of Friedrich von Wiesner MURAKAMI Ryo The immediate cause of the First World War was the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand at Sarajevo on 28 June 1914. Gavrilo Princip, who killed Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie, was a Serbian nationalist and a member of the Black Hand Society. The Austrian government thought that Serbia was behind the affair. In its response, Vienna sought to settle its decade-long dispute with Serbia. On 23 July 1914, the Austrian government gave an ultimatum to the Serbian government. Many researchers argue that Austria deliberately made demands that it knew Serbia could not accept. Furthermore, it is often indicated that Vienna’s ultimatum was not aimed at the Black Hand Society, but at the National Defense (in Serbian, Narodna Odbrana). Many researchers have carried out research into the diplomatic crisis (the so-called July Crisis) between the assassination at Sarajevo and the British declaration of war against Germany. Although Vienna’s declaration of war caused a chain reaction in Europe, historiographic studies still do not pay sufficient attention to either the process that led to the ultimatum, or to the Austrian justification for war against Serbia. In this article, I point out the importance of Friedrich von Wiesner, adviser on international law at the Austrian foreign ministry, during the July Crisis in Vienna. He participated by drawing up the ultimatum and he wrote the document (a memorandum) detailing charges against Serbia. -

Timeline of Start Of

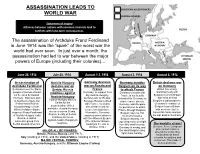

ASSASSINATION LEADS TO EUROPEAN ALLIED POWERS WORLD WAR CENTRAL POWERS Statement of Inquiry Alliances between nations with common interests lead to conflicts with long-term consequences. RUSSIA GERMANY GERMANY The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand FRANCE AUSTRIA- in June 1914 was the “spark” of the worst war the HUNGARY world had ever seen. In just over a month, the Bosnia assassination had led to war between the major OTTOMAN EMPIRE powers of Europe (including their colonies)… June 28, 1914 July 28, 1914 August 1-3, 1914 August 3, 1914 August 4, 1914 Assassination of Austria-Hungary Germany declares Germany invades Britain declares war Archduke Ferdinand declares war on war on Russia and Belgium on its way on Germany Serbia believes the Slavic Serbia; Russia France to attack France Britain has a long- people of Europe should mobilizes against Germany, to support their Germany’s border with standing treaty with Belgium in which Britain not be ruled by Austria- Austria-Hungary ally Austria-Hungary, France is too heavily Hungary. Bosnia is part declares war on Russia. defended for Germany to agreed to defend Austria-Hungary blames of Austria-Hungary, but Because Russia is allied attack France directly. Belgium’s independence. Serbia for the Serbia thinks Bosnia with France, Germany Germany asks Belgium Germany’s invasion of assassination of their should belong to them. also declares war on for permission to attack Belgium leaves Britain archduke. Austria-Hungary When Archduke (future France two days later. France through Belgium. with no choice but to declares war on Serbia. emperor) Franz-Ferdinand Meanwhile, Germany Belgium says no, but honor this treaty and join Russia, an ally of Serbia, of Austria-Hungary visits makes a secret alliance Germany invades the war against Germany. -

French Press, Public Opinion and the Murder of Franz Ferdinand In

French press, public opinion and the assassination of Franz Ferdinand (28 June-3 August 1914) How French society entered the Great war? Unlocking sources • The aim of this communication is quite simple: how new ways of getting access to digital contents (through technical process such as OCR and NER) give us the opportunity to understand how French society entered the First World War in August 1914? • Regarding this topic, I have studied both private archives and French press issues made available through the project Europeana 14-18 (chronologically from the 29 of June, the day after the assassination of Franz-Ferdinand , heir of the austro-hungarian monarchy in Sarajevo to the 3rd of August, the day of the declaration of war of Germany on France) • I have used two different technologies I will come back later on: the optical recognition of characters and the named entities recognition, a process we have developped thanks to another European project, Europeana Newspapers Unlocking sources • One of the main concern for me was also to assess the impact of the use of these automated processes applied to historical sources • This question is quite important as I strongly believe that the use of such technical process modify deeply our access and our understanding of historical sources (in other words how automated process lead to a new way of writing history) Starting point Emile Spring 1914 Starting point Letter sent to his family in law 31st of July 1914 French historiography • J-J Becker, How French entered the war, 1977) • If we consider the succession of events from the assassination of the archduke Franz-Ferdinand the 28th of June in Sarajevo to the declaration of war on France the 3rd of August, the point of view promoted by J.J. -

CAUSES of WORLD WAR I Objective: Analyze the Causes of World War I

CAUSES of WORLD WAR I Objective: Analyze the causes of World War I. Do Now: What are some holidays during which people celebrate pride in their national heritage? Causes of World War I - MANIA M ilitarism – policy of building up strong military forces to prepare for war Alliances - agreements between nations to aid and protect one another ationalism – pride in or devotion to one’s Ncountry I mperialism – when one country takes over another country economically and politically Assassination – murder of Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand Causes of WWI - Militarism Total Defense Expenditures for the Great Powers [Ger., A-H, It., Fr., Br., Rus.] in millions of £s (British pounds). 1870 1880 1890 1900 1910 1914 94 130 154 268 289 398 1910-1914 Increase in Defense Expenditures France 10% Britain 13% Russia 39% Germany 73% Causes of WWI - Alliances Triple Entente: Triple Alliance: Great Britain Germany France Austria-Hungary Russia Italy Causes of WWI - Nationalism Causes of WWI - Nationalism Pan-Germanism - movement to unify the people of all German speaking countries Germanic Countries Austria * Luxembourg Belgium Netherlands Denmark Norway Iceland Sweden Germany * Switzerland * Liechtenstein United * Kingdom * = German speaking country Causes of WWI - Nationalism Pan-Slavism - movement to unify all of the Slavic people Imperialism: European conquest of Africa Causes of WWI - Imperialism Causes of WWI - Imperialism The “Spark” Causes of WWI - Assassination Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand visited the city of Sarajevo in Bosnia – a country that was under the control of Austria. Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Duchess Sophie in Sarajevo, Bosnia, on June 28th, 1914. Causes of WWI - Assassination Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife were killed in Bosnia by a Serbian nationalist who believed that Bosnia should belong to Serbia. -

When Diplomats Fail: Aostrian and Rossian Reporting from Belgrade, 1914

WHEN DIPLOMATS FAIL: AOSTRIAN AND ROSSIAN REPORTING FROM BELGRADE, 1914 Barbara Jelavich The mountain of books written on the origins of the First World War have produced no agreement on the basic causes of this European tragedy. Their division of opinion reflects the situation that existed in June and July 1914, when the principal statesmen involved judged the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Habsburg throne, and its consequences from radically different perspectives. Their basic misunderstanding of the interests and viewpoints 'of the opposing sides contributed strongly to the initiation of hostilities. The purpose of this paper is to emphasize the importance of diplomatic reporting, particularly in the century before 1914 when ambassadors were men of influence and when their dispatches were read by those who made the final decisions in foreign policy. European diplomats often held strong opinions and were sometimes influenced by passions and. prejudices, but nevertheless throughout the century their activities contributed to assuring that this period would, with obvious exceptions, be an era of peace in continental affairs. In major crises the crucial decisions are always made by a very limited number of people no matter what the political system. Usually a head of state -- whether king, emperor, dictator, or president, together with those whom he chooses to consult, or a strong political leader with his advisers- -decides on the course of action. Obviously, in times of international tension these men need accurate information not only from their military staffs on the state of their and their opponent's armed forces and the strategic position of the country, but also expert reporting from their representatives abroad on the exact issues at stake and the attitudes of the other governments, including their immediate concerns and their historical background. -

Inheriting the Yugoslav Century: Art, History, and Generation

Inheriting the Yugoslav Century: Art, History, and Generation by Ivana Bago Department of Art, Art History and Visual Studies Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Kristine Stiles, Supervisor ___________________________ Mark Hansen ___________________________ Fredric Jameson ___________________________ Branislav Jakovljević ___________________________ Neil McWilliam Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Art, Art History and Visual Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 ABSTRACT Inheriting the Yugoslav Century: Art, History, and Generation by Ivana Bago Department of Art, Art History and Visual Studies Duke University ___________________________ Kristine Stiles, Supervisor ___________________________ Mark Hansen ___________________________ Fredric Jameson ___________________________ Branislav Jakovljević ___________________________ Neil McWilliam An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Art, Art History and Visual Studies in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 Copyright by Ivana Bago 2018 Abstract The dissertation examines the work contemporary artists, curators, and scholars who have, in the last two decades, addressed urgent political and economic questions by revisiting the legacies of the Yugoslav twentieth century: multinationalism, socialist self-management, non- alignment, and -

How Did the First World War Start?

How Did the First World War Start? The First World War, often called The Great War, was an enormous and devastating event in the early 1900s. Over 17 million people were killed and it had a massive effect on politics and countries all over the world. But why did the First World War happen and what caused it? The major catalyst for the start of the First World War was the assassination of a man named Archduke Franz Picture associated with the arrest of Gavrilo Princip Ferdinand. However, there were other events which led to the start of the war. The start of the 1900s in Europe was a time of peace for many. In most places, wealth was growing and people were comfortable and countries were thriving. At this time, some European countries, mainly France and Britain, owned and controlled countries in Asia and Africa, as well as some areas of other continents. This was because these countries helped to improve the wealth of Europe. Before the First World War, many countries were allies with one another and they had defence treaties. This meant that if war was declared on one of the countries, the other members of the alliance had to go to war to help them. There were two main alliances, one between Britain, France and Russia called ‘The Triple Entente’ and one between Germany and Austria-Hungary called ‘The Central Powers’. One of the reasons for these treaties was that, during the early 1900s, each country wanted to be the most powerful. Germany in particular, who did not control many territories, began building warships as they wished to become the most powerful country. -

Germany Austria-Hungary Russia France Britain Italy Belgium

Causes of The First World War Europe 1914 Britain Russia Germany Belgium France Austria-Hungary Serbia Italy Turkey What happened? The incident that triggered the start of the war was a young Serb called Gavrilo Princip shooting the Archduke of Austria, Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo. Gavrilo Princip Franz Ferdinand This led to... The Cambria Daily Leader, 29 June 1914 The Carmarthen Journal and South Wales Weekly Adver@ser, 31 July, 1914 How did this incident create a world war? Countries formed partnerships or alliances with other countries to protect them if they were attacked. After Austria Hungary declared war on Serbia others joined in to defend their allies. Gavrilo Princip shoots the Arch- duke of Austria, Franz Ferdinand. Britain and Italy has an France have Austria- agreement with an Hungary Germany agreement defends Germany Russia and with Russia defends declares Austria- Hungary Austria- and join the Serbia war on Hungary war Serbia but refuses to join the war. Timeline - first months of War 28 June 1914 - Gavrilo Princip shoots 28 June, 1914 the Archduke of Austria, Franz Ferdiand and his wife in Sarajevo 28 July 1914 - Austria-Hungary declares war against Serbia. 28 July 1914 - Russia prepares for war against Austria-Hungary to protect Serbia. 4 August, 1914 1 August 1914 - Germany declares war against Russia to support Austria- Hungary. 3 August 1914 - Germany and France declare war against each other. 4 August 1914 - Germany attacks France through Belgium. Britain declares war against Germany to defend Belgium. War Begins - The Schlieffen Plan The Germans had been preparing for war for years and had devised a plan known as the ‘Schlieffen Plan’ to attack France and Russia. -

PRIMARY SOURCE the Murder of Archduke Franz Ferdinand

mwh10a-IDR-O413 12/15/2003 3:21 PM Page 9 Name Date CHAPTER PRIMARY SOURCE The Murder of Archduke Franz 13 Ferdinand Section 1 by Borijove Jevtic On June 28, 1914, Austria-Hungary’s Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated by Gavrilo Princip in Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia. This excerpt from an eyewit- ness account by a fellow conspirator in the assassination plot explains why the attack took place, what happened during the attack, and how Princip, the 19- year-old Serbian assassin, was captured. Why did the Archduke’s plan to visit Sarajevo on June 28 prompt such a violent response? he little clipping . declared that the Austrian The road to the maneuvers was shaped like the TArchduke Franz Ferdinand would visit letter V, making a sharp turn at the bridge over the Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia, June 28, to direct River Nilgacka. Franz Ferdinand’s car . was forced army maneuvers in the neighbouring mountains. to slow down for the turn. Here Princip had taken How dared Franz Ferdinand, not only the rep- his stand. resentative of the oppressor but in his own person As the car came abreast he stepped forward from an arrogant tyrant, enter Sarajevo on that day? the curb, drew his automatic pistol from his coat and Such an entry was a studied insult. fired two shots. The first struck the wife of the arch- June 28 is a date engraved deeply in the heart duke, the Archduchess Sofia, in the abdomen. She of every Serb. It is the day on which the old was an expectant mother. -

Conrad Von Hötzendorf and the “Smoking Gun”: a Biographical Examination of Responsibility and Traditions of Violence Against Civilians in the Habsburg Army 55

1914: Austria-Hungary, the Origins, and the First Year of World War I Günter Bischof, Ferdinand Karlhofer (Eds.) Samuel R. Williamson, Jr. (Guest Editor) CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES | VOLUME 23 uno press innsbruck university press Copyright © 2014 by University of New Orleans Press, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to UNO Press, University of New Orleans, LA 138, 2000 Lakeshore Drive. New Orleans, LA, 70119, USA. www.unopress.org. Printed in the United States of America Design by Allison Reu Cover photo: “In enemy position on the Piave levy” (Italy), June 18, 1918 WK1/ALB079/23142, Photo Kriegsvermessung 5, K.u.k. Kriegspressequartier, Lichtbildstelle Vienna Cover photo used with permission from the Austrian National Library – Picture Archives and Graphics Department, Vienna Published in the United States by Published and distributed in Europe University of New Orleans Press by Innsbruck University Press ISBN: 9781608010264 ISBN: 9783902936356 uno press Contemporary Austrian Studies Sponsored by the University of New Orleans and Universität Innsbruck Editors Günter Bischof, CenterAustria, University of New Orleans Ferdinand Karlhofer, Universität Innsbruck Assistant Editor Markus Habermann -

B33310154.Pdf

L 9fc 31 PISL-14 COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA SOM S-6S DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION STATE LIBRARY HARRIS BURH In case of failure to return the books the borrower agrees to pay the original price of the same, or to replace them with other copies. The last borrower is held responsible for any mutilation. Return this book on or before the last date stamped below. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/july1400emil JULY '14 By EMIL LUDWIG Author of "Goethe," "WilheSm HoherjzolJe™," etc. Translated from the German by C. A. MACARTNEY " <5A man need not have been a "Bismarck to prevent this most idiotic of all wars." BALLIN With 16 Illustrations NEW YORK : LONDON G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS JULY '14 ^> Copyright, 1929 by G. P. Putnam's Sons First Printing, Nov., 1929 Second " Nov., 1929 Third " Jan., 1930 e in the United States of America To Our Sons—In Warning 234821 The thanks of the Translator and the Publishers are due to Dr. J. F. Muirhead for reading the translation both in typescript and in proof and for making very many valuable suggestions. FOREWORD THE war-guilt belongs to all Europe; re- searches in every country have proved this. Germany's exclusive guilt or Germany's innocence are fairy-tales for children on both sides of the Rhine. What country wanted the war? Let us put a different question: What circles in every country wanted, facilitated, or began the war? If, instead of a horizontal section through Europe, we take a vertical section through society, we find that the sum of guilt was in the Cabinets, the sum of innocence in the streets of Europe.