When Diplomats Fail: Aostrian and Rossian Reporting from Belgrade, 1914

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wwi 1914 - 1918

ABSTRACT This booklet will introduce you to the key events before and during the First World War. Taking place from 1914 – 1918, millions of people across the world lost their lives in what was supposed to be ‘the war to end all wars’. Fighting on this scale had never been seen before. The work in this booklet will help you understand why such a horrific conflict begun. Ms Marsh WWI 1914 - 1918 Year 8 History Why did the First World War begin? L.O: I can explain the causes of the First World War. 1. In what year did the war begin? 2. In what year did the war end? 3. How many years did it last? (Do now answers at end of booklet) The First World War begun in August 1914. It took the world by surprise, and seemed to happen overnight. In reality, tension between countries in Europe had been increasing for some years before. The final event that triggered war, the assassination of a young heir to the Austria – Hungary throne, demonstrates how this tension had been building. Europe in the early 20th century was a place where newly formed countries such as Italy started to challenge the dominance of countries with empires. An empire is when one country rules over others around the world. Some countries began to demand their independence and did not want to be ruled by an empire. The map opposite shows just how vast the empires of Europe were; Britain had control of Australia, New Zealand, Canada, East and South Africa and India. -

Summary 7 (2017)

Japan Border Review, No.Summary 7 (2017) Summary Austria-Hungary’s Ultimatum of 23 July 1914 Reconsidered: The Background of Vienna’s Decision-Making in the Memorandum of Friedrich von Wiesner MURAKAMI Ryo The immediate cause of the First World War was the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand at Sarajevo on 28 June 1914. Gavrilo Princip, who killed Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie, was a Serbian nationalist and a member of the Black Hand Society. The Austrian government thought that Serbia was behind the affair. In its response, Vienna sought to settle its decade-long dispute with Serbia. On 23 July 1914, the Austrian government gave an ultimatum to the Serbian government. Many researchers argue that Austria deliberately made demands that it knew Serbia could not accept. Furthermore, it is often indicated that Vienna’s ultimatum was not aimed at the Black Hand Society, but at the National Defense (in Serbian, Narodna Odbrana). Many researchers have carried out research into the diplomatic crisis (the so-called July Crisis) between the assassination at Sarajevo and the British declaration of war against Germany. Although Vienna’s declaration of war caused a chain reaction in Europe, historiographic studies still do not pay sufficient attention to either the process that led to the ultimatum, or to the Austrian justification for war against Serbia. In this article, I point out the importance of Friedrich von Wiesner, adviser on international law at the Austrian foreign ministry, during the July Crisis in Vienna. He participated by drawing up the ultimatum and he wrote the document (a memorandum) detailing charges against Serbia. -

Timeline of Start Of

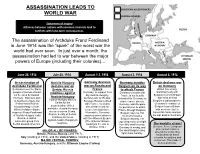

ASSASSINATION LEADS TO EUROPEAN ALLIED POWERS WORLD WAR CENTRAL POWERS Statement of Inquiry Alliances between nations with common interests lead to conflicts with long-term consequences. RUSSIA GERMANY GERMANY The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand FRANCE AUSTRIA- in June 1914 was the “spark” of the worst war the HUNGARY world had ever seen. In just over a month, the Bosnia assassination had led to war between the major OTTOMAN EMPIRE powers of Europe (including their colonies)… June 28, 1914 July 28, 1914 August 1-3, 1914 August 3, 1914 August 4, 1914 Assassination of Austria-Hungary Germany declares Germany invades Britain declares war Archduke Ferdinand declares war on war on Russia and Belgium on its way on Germany Serbia believes the Slavic Serbia; Russia France to attack France Britain has a long- people of Europe should mobilizes against Germany, to support their Germany’s border with standing treaty with Belgium in which Britain not be ruled by Austria- Austria-Hungary ally Austria-Hungary, France is too heavily Hungary. Bosnia is part declares war on Russia. defended for Germany to agreed to defend Austria-Hungary blames of Austria-Hungary, but Because Russia is allied attack France directly. Belgium’s independence. Serbia for the Serbia thinks Bosnia with France, Germany Germany asks Belgium Germany’s invasion of assassination of their should belong to them. also declares war on for permission to attack Belgium leaves Britain archduke. Austria-Hungary When Archduke (future France two days later. France through Belgium. with no choice but to declares war on Serbia. emperor) Franz-Ferdinand Meanwhile, Germany Belgium says no, but honor this treaty and join Russia, an ally of Serbia, of Austria-Hungary visits makes a secret alliance Germany invades the war against Germany. -

When Fear Is Substituted for Reason: European and Western Government Policies Regarding National Security 1789-1919

WHEN FEAR IS SUBSTITUTED FOR REASON: EUROPEAN AND WESTERN GOVERNMENT POLICIES REGARDING NATIONAL SECURITY 1789-1919 Norma Lisa Flores A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2012 Committee: Dr. Beth Griech-Polelle, Advisor Dr. Mark Simon Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Michael Brooks Dr. Geoff Howes Dr. Michael Jakobson © 2012 Norma Lisa Flores All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Beth Griech-Polelle, Advisor Although the twentieth century is perceived as the era of international wars and revolutions, the basis of these proceedings are actually rooted in the events of the nineteenth century. When anything that challenged the authority of the state – concepts based on enlightenment, immigration, or socialism – were deemed to be a threat to the status quo and immediately eliminated by way of legal restrictions. Once the façade of the Old World was completely severed following the Great War, nations in Europe and throughout the West started to revive various nineteenth century laws in an attempt to suppress the outbreak of radicalism that preceded the 1919 revolutions. What this dissertation offers is an extended understanding of how nineteenth century government policies toward radicalism fostered an environment of increased national security during Germany’s 1919 Spartacist Uprising and the 1919/1920 Palmer Raids in the United States. Using the French Revolution as a starting point, this study allows the reader the opportunity to put events like the 1848 revolutions, the rise of the First and Second Internationals, political fallouts, nineteenth century imperialism, nativism, Social Darwinism, and movements for self-government into a broader historical context. -

Belgrade - Budapest - Ljubljana - Zagreb Sample Prospect

NOVI SAD BEOGRAD Železnička 23a Kraljice Natalije 78 PRODAJA: PRODAJA: 021/422-324, 021/422-325 (fax) 011/3616-046 [email protected] [email protected] KOMERCIJALA: KOMERCIJALA 021/661-07-07 011/3616-047 [email protected] [email protected] FINANSIJE: [email protected] LICENCA: OTP 293/2010 od 17.02.2010. www.grandtours.rs BELGRADE - BUDAPEST - LJUBLJANA - ZAGREB SAMPLE PROSPECT 1st day – BELGRADE The group is landing in Serbia after which they get on the bus and head to the downtown Belgrade. Sightseeing of the Belgrade: National Theatre, House of National Assembly, Patriarchy of Serbian Orthodox Church etc. Upon request of the group, Tour of The Saint Sava Temple could be organized. The tour of Kalemegdan fortress, one of the biggest fortress that sits on the confluence of Danube and Sava rivers. Upon request of the group, Avala Tower visit could be organized, which offers a view of mountainous Serbia on one side and plain Serbia on the other. Departure for the hotel. Dinner. Overnight stay. 2nd day - BELGRADE - NOVI SAD – BELGRADE Breakfast. After the breakfast the group would travel to Novi Sad, consider by many as one of the most beautiful cities in Serbia. Touring the downtown's main streets (Zmaj Jovina & Danube street), Danube park, Petrovaradin Fortress. The trip would continue towards Sremski Karlovci, a beautiful historic place close to the city of Novi Sad. Great lunch/dinner option in Sremski Karlovci right next to the Danube river. After the dinner, the group would head back to the hotel in Belgrade. -

Divergence of Myrobalan (Prunus Cerasifera Ehrh.) Types on the Territory of Serbia

UDC 575: 634.22 Original scientific paper DIVERGENCE OF MYROBALAN (Prunus cerasifera Ehrh. ) TYPES ON THE TERRITORY OF SERBIA Dragan NIKOLI Ć and Vera RAKONJAC Faculty of Agriculture, Belgrade-Zemun, Serbia Nikoli ć D. and V. Rakonjac (2007): Divergence of myrobalan (Prunus cerasifera ehrh.) types on the territory of Serbia.. – Genetika, Vol. 39, No. 3, 333 - 342. Variability of some more prominent pomological characteristics was examined in three regions of Serbia (central, western, southern). In all the regions, significant variability of all studied characteristics was established. However, no specifics were manifested between regions, therefore, identical types emerge in all the regions. This is indicated by similar intervals of variation as well as similar mean values of characteristics per region. The obtained results lead to the conclusion that the entire territory of Serbia should be observed as a unique myrobalan population with highly expressed polymorphism of characteristics. To preserve genetic variability of myrobalan, collection is recommended for those types that were arranged into various groups and subgroups according to the results of cluster analysis. Key word: myrobalan, natural population, pomological characteristics, phenotypic variability ______________________________ Corresponding author: Dragan Nikoli ć, Faculty of Agriculture, Nemanjina 6, 11080 Belgrade-Zemun, Serbia, e-mail: [email protected] 334 GENETIKA, Vol. 39, No. 3, 333 -342, 2007. INTRODUCTION The myrobalan or cherry plum ( Prunus cerasifera Ehrh.) is native to southeastern Europe or southwestern Asia. Its seedlings are used for the most part as a rootstock for plum (W EINBERGER , 1975; E RBIL and S OYLU , 2002), but lesser for apricot (D IMITROVA and M ARINOV , 2002) and almond and peach (D UVAL et al ., 2004). -

The Purpose of the First World War War Aims and Military Strategies Schriften Des Historischen Kollegs

The Purpose of the First World War War Aims and Military Strategies Schriften des Historischen Kollegs Herausgegeben von Andreas Wirsching Kolloquien 91 The Purpose of the First World War War Aims and Military Strategies Herausgegeben von Holger Afflerbach An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Schriften des Historischen Kollegs herausgegeben von Andreas Wirsching in Verbindung mit Georg Brun, Peter Funke, Karl-Heinz Hoffmann, Martin Jehne, Susanne Lepsius, Helmut Neuhaus, Frank Rexroth, Martin Schulze Wessel, Willibald Steinmetz und Gerrit Walther Das Historische Kolleg fördert im Bereich der historisch orientierten Wissenschaften Gelehrte, die sich durch herausragende Leistungen in Forschung und Lehre ausgewiesen haben. Es vergibt zu diesem Zweck jährlich bis zu drei Forschungsstipendien und zwei Förderstipendien sowie alle drei Jahre den „Preis des Historischen Kollegs“. Die Forschungsstipendien, deren Verleihung zugleich eine Auszeichnung für die bisherigen Leis- tungen darstellt, sollen den berufenen Wissenschaftlern während eines Kollegjahres die Möglich- keit bieten, frei von anderen Verpflichtungen eine größere Arbeit abzuschließen. Professor Dr. Hol- ger Afflerbach (Leeds/UK) war – zusammen mit Professor Dr. Paul Nolte (Berlin), Dr. Martina Steber (London/UK) und Juniorprofessor Simon Wendt (Frankfurt am Main) – Stipendiat des Historischen Kollegs im Kollegjahr 2012/2013. Den Obliegenheiten der Stipendiaten gemäß hat Holger Afflerbach aus seinem Arbeitsbereich ein Kolloquium zum Thema „Der Sinn des Krieges. Politische Ziele und militärische Instrumente der kriegführenden Parteien von 1914–1918“ vom 21. -

Felipe Angeles| Military Intellectual of the Mexican Revolution, 1913--1915

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1988 Felipe Angeles| Military intellectual of the Mexican Revolution, 1913--1915 Ronald E. Craig The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Craig, Ronald E., "Felipe Angeles| Military intellectual of the Mexican Revolution, 1913--1915" (1988). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 2333. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/2333 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT ACT OF 1976 THIS IS AN UNPUBLISHED MANUSCRIPT IN WHICH COPYRIGHT SUBSISTS, ANY FURTHER REPRINTING OF ITS CONTENTS MUST BE APPROVED BY THE AUTHOR, MANSFIELD LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA DATE198ft FELIPE ANGELES: MILITARY INTELLECTUAL OF THE MEXICAN REVOLUTION 1913-1915 by Ronald E. Craig B.A., University of Montana, 1985 Presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Montana 1988 Chairman^ Bagprd—of—Examiners Dean, Graduate School / & t / Date UMI Number: EP36373 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

French Press, Public Opinion and the Murder of Franz Ferdinand In

French press, public opinion and the assassination of Franz Ferdinand (28 June-3 August 1914) How French society entered the Great war? Unlocking sources • The aim of this communication is quite simple: how new ways of getting access to digital contents (through technical process such as OCR and NER) give us the opportunity to understand how French society entered the First World War in August 1914? • Regarding this topic, I have studied both private archives and French press issues made available through the project Europeana 14-18 (chronologically from the 29 of June, the day after the assassination of Franz-Ferdinand , heir of the austro-hungarian monarchy in Sarajevo to the 3rd of August, the day of the declaration of war of Germany on France) • I have used two different technologies I will come back later on: the optical recognition of characters and the named entities recognition, a process we have developped thanks to another European project, Europeana Newspapers Unlocking sources • One of the main concern for me was also to assess the impact of the use of these automated processes applied to historical sources • This question is quite important as I strongly believe that the use of such technical process modify deeply our access and our understanding of historical sources (in other words how automated process lead to a new way of writing history) Starting point Emile Spring 1914 Starting point Letter sent to his family in law 31st of July 1914 French historiography • J-J Becker, How French entered the war, 1977) • If we consider the succession of events from the assassination of the archduke Franz-Ferdinand the 28th of June in Sarajevo to the declaration of war on France the 3rd of August, the point of view promoted by J.J. -

Montenegro's Tribal Legacy

WARNING! The views expressed in FMSO publications and reports are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. Montenegro's Tribal Legacy by Major Steven C. Calhoun, US Army Foreign Military Studies Office, Fort Leavenworth, KS. This article appeared in Military Review July-August 2000 The mentality of our people is still very patriarchal. Here the knife, revenge and a tribal (plemenski) system exist as nowhere else.1 The whole country is interconnected and almost everyone knows everyone else. Montenegro is nothing but a large family—all of this augurs nothing good. —Mihajlo Dedejic2 When the military receives an order to deploy into a particular area, planners focus on the terrain so the military can use the ground to its advantage. Montenegro provides an abundance of terrain to study, and it is apparent from the rugged karst topography how this tiny republic received its moniker—the Black Mountain. The territory of Montenegro borders Croatia, Bosnia- Herzegovina, Serbia and Albania and is about the size of Connecticut. Together with the much larger republic of Serbia, Montenegro makes up the current Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY). But the jagged terrain of Montenegro is only part of the military equation. Montenegro has a complex, multilayered society in which tribe and clan can still influence attitudes and loyalties. Misunderstanding tribal dynamics can lead a mission to failure. Russian misunderstanding of tribal and clan influence led to unsuccessful interventions in Afghanistan and Chechnya.3 In Afghanistan, the rural population's tribal organization facilitated their initial resistance to the Soviets. -

UNDER ORDERS: War Crimes in Kosovo Order Online

UNDER ORDERS: War Crimes in Kosovo Order online Table of Contents Acknowledgments Introduction Glossary 1. Executive Summary The 1999 Offensive The Chain of Command The War Crimes Tribunal Abuses by the KLA Role of the International Community 2. Background Introduction Brief History of the Kosovo Conflict Kosovo in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia Kosovo in the 1990s The 1998 Armed Conflict Conclusion 3. Forces of the Conflict Forces of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia Yugoslav Army Serbian Ministry of Internal Affairs Paramilitaries Chain of Command and Superior Responsibility Stucture and Strategy of the KLA Appendix: Post-War Promotions of Serbian Police and Yugoslav Army Members 4. march–june 1999: An Overview The Geography of Abuses The Killings Death Toll,the Missing and Body Removal Targeted Killings Rape and Sexual Assault Forced Expulsions Arbitrary Arrests and Detentions Destruction of Civilian Property and Mosques Contamination of Water Wells Robbery and Extortion Detentions and Compulsory Labor 1 Human Shields Landmines 5. Drenica Region Izbica Rezala Poklek Staro Cikatovo The April 30 Offensive Vrbovac Stutica Baks The Cirez Mosque The Shavarina Mine Detention and Interrogation in Glogovac Detention and Compusory Labor Glogovac Town Killing of Civilians Detention and Abuse Forced Expulsion 6. Djakovica Municipality Djakovica City Phase One—March 24 to April 2 Phase Two—March 7 to March 13 The Withdrawal Meja Motives: Five Policeman Killed Perpetrators Korenica 7. Istok Municipality Dubrava Prison The Prison The NATO Bombing The Massacre The Exhumations Perpetrators 8. Lipljan Municipality Slovinje Perpetrators 9. Orahovac Municipality Pusto Selo 10. Pec Municipality Pec City The “Cleansing” Looting and Burning A Final Killing Rape Cuska Background The Killings The Attacks in Pavljan and Zahac The Perpetrators Ljubenic 11. -

The Argument of the Broken Pane', Suffragette Consumerism And

1 TITLE PAGE ‘The Argument of the Broken Pane’, Suffragette Consumerism and Newspapers by Jane Chapman, Professor of Communications, Lincoln University School of Journalism, Campus Way, Lincoln LN6 7TS, tel. 01522 886963, email: [email protected] 2 Abstract Within the cutthroat world of newspapers advertising the newspapers of Britain’s Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) Votes for Women and The Suffragette managed to achieve a balance that has often proved to be an impossible challenge for social movement press – namely the maintenance of a highly political stance whilst simultaneously exploiting the market system with advertising and merchandising. When the militant papers advocated window smashing of West End stores in 1912 - 13, the companies who were the target still took advertisements. Why? What was the relationship between news values, militant violence, and advertising income? ‘Do-it-yourself’ journalism operated within a context of ethical consumerism and promotionally orientated militancy. This resulted in newspaper connections between politics, commerce and a distinct market profile, evident in the customization of advertising, retailer dialogue with militants, and longer-term loyalty – symptomatic of a wider trend towards newspaper commercialism during this period. Keywords: suffragettes, Votes for Women, The Suffragette, window smashing, advertisers, ethical consumerism, WSPU. Main text Advertisers ‘judge the character of the reader by the character of the periodical’ (George French, Advertising: the Social and Economic Problem, 1915) ‘The argument of the broken window pane is the most valuable argument in modern politics’ (Emmeline Pankhurst, Votes for Women, 23 Feb.1912). Introduction and contexts One of the great achievements of the many and various activist women’s groups in Britain was their ability – despite, or more likely because of the movement’s diversity – to maintain a high, if fluctuating, public profile for a sustained period in history.