The Works of Thomas Carlyle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Carlyle Society Papers

THE CARLYLE SOCIETY SESSION 2011-2012 OCCASIONAL PAPERS 24 • Edinburgh 2011 1 2 President’s Letter With another year’s papers we approach an important landmark in Carlyle studies. A full programme for the Society covers the usual wide range (including our mandated occasional paper on Burns), and we will also make room for one of the most important of Thomas’s texts, the Bible. 2012 sees a milestone in the publication of volume 40 of the Carlyle Letters, whose first volumes appeared in 1970 (though the project was a whole decade older in the making). There will be a conference (10-12 July) of academic Carlyle specialists in Edinburgh to mark the occasion – part of the wider celebrations that the English Literature department will be holding to celebrate its own 250th anniversary of Hugh Blair’s appointment to the chair of Rhetoric, making Edinburgh the first recognisable English department ever. The Carlyle Letters have been an important part of the research activity of the department for nearly half a century, and there will also be a public lecture later in November (when volume 40 itself should have arrived in the country from the publishers in the USA). As part of the conference there will be a Thomas Green lecture, and members of the Society will be warmly invited to attend this and the reception which follows. Details are in active preparation, and the Society will be kept informed as the date draws closer. Meantime work on the Letters is only part of the ongoing activity, on both sides of the Atlantic, to make the works of both Carlyles available, and to maintain the recent burst of criticism which is helping make their importance in the Victorian period more and more obvious. -

Heroic Individualism: the Hero As Author in Democratic Culture Alan I

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2006 Heroic individualism: the hero as author in democratic culture Alan I. Baily Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Baily, Alan I., "Heroic individualism: the hero as author in democratic culture" (2006). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1073. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1073 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. HEROIC INDIVIDUALISM: THE HERO AS AUTHOR IN DEMOCRATIC CULTURE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Political Science by Alan I. Baily B.S., Texas A&M University—Commerce, 1999 M.A., Louisiana State University, 2003 December, 2006 It has been well said that the highest aim in education is analogous to the highest aim in mathematics, namely, to obtain not results but powers , not particular solutions but the means by which endless solutions may be wrought. He is the most effective educator who aims less at perfecting specific acquirements that at producing that mental condition which renders acquirements easy, and leads to their useful application; who does not seek to make his pupils moral by enjoining particular courses of action, but by bringing into activity the feelings and sympathies that must issue in noble action. -

The Scopic Past and the Ethics of the Gaze

Ivan Illich Kreftingstr. 16 D - 28203 Bremen THE SCOPIC PAST AND THE ETHICS OF THE GAZE A plea for the historical study of ocular perception Filename and date: SCOPICPU.DOC Status: To be published in: Ivan Illich, Mirror II (working title). Copyright Ivan Illich. For further information please contact: Silja Samerski Albrechtstr.19 D - 28203 Bremen Tel: +49-(0)421-7947546 e-mail: [email protected] Ivan Illich: The Scpoic Past and the ethics of the Gaze 2 Ivan Illich THE SCOPIC PAST AND THE ETHICS OF THE GAZE A plea for the historical study of ocular perception1 We want to treat a perceptual activity as a historical subject. There are histories of the rise and fall of the Roman Empire, of the formation of a working class in Great Britain, of porridge in medieval Europe. We ourselves have explored the history of the experienced (female) body in the West. Now we wish to outline the domain for a history of the gaze - der Blick, le regard, opsis.2 The action of seeing is shaped differently in different epochs. We assume that the gaze can be a human act. Hence, our historical survey is carried out sub specie boni; we wish to explore the possibilities of seeing in the perspective of the good. In what ways is this action ethical? The question arose for us when we saw the necessity of defending the integrity and clarity of our senses - our sense experience - against the insistent encroachments of multimedia from cyberspace. From our backgrounds in history, we felt that we had to resist the dissolution of the past by seemingly sophisticated postmodern catch phrases, for example, the deconstruction of conversation into a process of communication. -

The Carlyle Society

THE CARLYLE SOCIETY SESSION 2006-2007 OCCASIONAL PAPERS 19 • Edinburgh 2006 President’s Letter This number of the Occasional Papers outshines its predecessors in terms of length – and is a testament to the width of interests the Society continues to sustain. It reflects, too, the generosity of the donation which made this extended publication possible. The syllabus for 2006-7, printed at the back, suggests not only the health of the society, but its steady move in the direction of new material, new interests. Visitors and new members are always welcome, and we are all warmly invited to the annual Scott lecture jointly sponsored by the English Literature department and the Faculty of Advocates in October. A word of thanks for all the help the Society received – especially from its new co-Chair Aileen Christianson – during the President’s enforced absence in Spring 2006. Thanks, too, to the University of Edinburgh for its continued generosity as our host for our meetings, and to the members who often anonymously ensure the Society’s continued smooth running. 2006 saw the recognition of the Carlyle Letters’ international importance in the award by the new Arts and Humanities Research Council of a very substantial grant – well over £600,000 – to ensure the editing and publication of the next three annual volumes. At a time when competition for grants has never been stronger, this is a very gratifying and encouraging outcome. In the USA, too, a very substantial grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities means that later this year the eCarlyle project should become “live” on the internet, and subscribers will be able to access all the volumes to date in this form. -

Colonization, Education, and the Formation of Moral Character: Edward Gibbon Wakefield's a Letter from Sydney

1 Historical Studies in Education / Revue d’histoire de l’éducation ARTICLES / ARTICLES Colonization, Education, and the Formation of Moral Character: Edward Gibbon Wakefield’s A Letter from Sydney Bruce Curtis Carleton University ABSTRacT Edward Gibbon Wakefield proposed a scheme of “systematic colonization” that he claimed would guarantee the formation of civilized moral character in settler societies at the same time as it reproduced imperial class relations. The scheme, which was first hatched after Wakefield read Robert Gourlay’s A Statistical Account of Upper Canada, inverted the dominant under- standing of the relation between school and society. Wakefield claimed that without systematic colonization, universal schooling would be dangerous and demoralizing. Wakefield intervened in contemporary debate about welfare reform and population growth, opposing attempts to enforce celibacy on poor women and arguing that free enjoyment of “animal liberty” made women both moral and beautiful. RÉSUMÉ Edward Gibbon Wakefield propose que son programme de « colonisation systématique » ga- rantirait la formation de colons au caractère moral et civilisé. Ce programme, né d’une pre- mière lecture de l’oeuvre de Robert Gourlay, A Statistical Account of Upper Canada, contri- buerait à reproduire la structure des classes sociales impériales dans les colonies. Son analyse inverse la relation dominante entre école et société entretenue par la plupart de réformateurs de l’éducation. Sans une colonisation systématique, prétend Wakefield, la scolarisation universelle serait cause de danger politique et de démoralisation pour la société. Wakefield intervient dans le débat contemporain entourant les questions d’aide sociale et de croissance de la population. Il s’oppose aux efforts d’imposer le célibat au femmes pauvres et il argumente que l’expression de leur ‘liberté animale’ rend les femmes morales et belles. -

Catalogue-Assunta-Cassa-English.Pdf

ASSUNTA CASSA 1st edition - June 2017 graphics: Giuseppe Bacci / Daniele Primavera photography: Emanuele Santori translations: Angela Arnone printed by Fastedit - Acquaviva Picena (AP) e-mail: [email protected] website: www.assuntacassa.it Assunta Cassa beyond the horizon edited by Giuseppe Bacci foreward by Giuseppe Marrone critical texts by Rossella Frollà, Anna Soricaro, Giuseppe Bacci 4 - Assunta Cassa - Beyond the horizon The Quest of Assunta Cassa for Delight and Dynamic Beauty Giuseppe Marrone Sensuality, movement, technique whose gesture, form and that rears up when least expected, reaching the apex and trac- matter are scented with the carnal thrill of dance it conveys, ing out perceptual geometries that perhaps no one thought compelling it on the eye, calling out to it and enticing the viewer, could be experimented. the recipient of the work who is dazed by an emotion stronger The art of Assunta Cassa has something primal in its emotional than delighted connection, and feels the inner turmoil triggered factor, no one should miss the thrill of experiencing her works by the virtuous explosions of colour and matter. The subject, in person, absorbing some of that passion, which enters the the dance, the movement, the steps that shift continuous exist- mind first and then sinks deeper into the spheres of perception. ence, igniting a split second and fixing it forever on the canvas. Sensuality and love, tenderness and passion, move with and Dynamic eroticism, rising yet immobile, fast, uncontrollable in in the dancing figures, which surprise with their natural seeking mind and in passion, able to erupt in a flash and unleash the of pleasure in the gesture, the beauty of producing a human fiercest emotion, the sheer giddiness of the most intense per- movement, again with sheer spontaneity, finding the refined ception. -

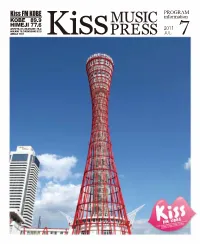

Musicpress.Pdf

スルッとスキニー&億千米 サンプルセットプレゼント中!! Kiss FM KOBE Event Report あ の『 億 千 米 』が パ ウ ダ ー タ イ プ に な っ て 新 登 場 ! ! 2011.6.4 sat @KOBE 植物性乳酸菌で女性の悩みをサポート 6月4日土曜日。週末の三宮の一角、イル・アルバータ神戸の前には鮮やか な黄色の[yellow tail]のフラッグが立ち並んでいた。そこに訪れるのは、 Kiss FMのイベント応募で選ばれた15組30名のワイン好きキスナー達。 店内に入ると、まず目に入るのは入り口近くに置かれた大きなグラス。しか もこちらには、オレンジジュース10Lに赤ワイン16本を注いだという、な んと本物のカクテルが。向かいのバーカウンター横には、セルフでカクテル を作れるスペースも設置されており、自分好みの味を楽しめるようになっ ている。イベントのMCを務めるのは、ワイン好きとしても知られるサウン ド ク ル ー ・ R I B E K A 。こ の 日 の コ ン セ プ ト“ ワ イ ン を 気 軽 に 楽 し む ”た め に 用意されたオリジナルカクテルが紹介される。 グレープフルーツを合わせ、酸味とその美しい青色が見た目にも爽やかな ブルーバブルス。イチゴとオレンジの香りにヨーグルト、 薄いピンク色が女性にも喜ばれそうなピンクテイル。カ シスとコーラによってジュースのように飲みやすいレッド テイル。そんなワインカクテルにぴったりな、イル・アル バータ特製の料理も次々と運ばれ、参加者達は舌鼓を打 お米の乳酸菌を、発酵技術で増やしました。 ちつつワインをゆったりと楽しんだ。 玄米食が苦手な人も思わずにっこりの美味しさです。 この日スペシャルトークゲストとして登場したのはmihimaru GTの 二人。告知なしで目の前に現れたシークレットアーティストに、会場 の歓声が上がる。芦屋出身で、神戸もよく訪れていたというヴォーカ ルhiroko。テーブルに置かれた3種類のカクテルを飲みながら「めっ ち ゃ 美 味 し い ! 」と 関 西 弁 で 嬉 し そ う に 微 笑 ん だ 。R I B E K A が「 ガ ン ガン飲んではるんですけど」と笑う通り、「美味しくて全部飲み干し たい!」と観客を和ませる良い飲みっぷりを披露。新曲『マスターピー Kiss MUSIC PRESS読者限定 ス』の作成秘話や、ソロ活動を経てこれからのmihimaru GTについ てカクテルpartyならではの親しみある雰囲気で語ってくれた。 サ ン プル セットプレ ゼ ント !! 次に登場したのは、ライブゲストのザッハトルテ。ジャズを中心と 下記よりご応募いただいた皆様の中から『スルッとスキ し た 多 ジ ャン ル の 楽 曲 を ア コ ー デ ィ オ ン・ギ タ ー・チ ェ ロ と い う 変 ニー!』3gスティック×5本と億千米25g×2袋を 則的にも思える構成で演奏する彼らだけあって、それぞれの髪型 セットにして300名様にプレゼントいたします! も か な り 個 性 的 。し か し 、一 音 鳴 ら せ ば「 窓 の 外 に 見 え る 三 宮 の 景 色 が 、ま る で パ リ の 街 並 み 」と R I B E K A も 語 る よ う に 、独 特 の 空 気 ■応募方法 感がその場にいる人々の前に作り出される。『素敵な1日』や『それ Kiss FM KOBEのサイトトップページ右側にあるプレゼント パソコン 欄から『スルッとスキニー!&億千米 サンプルセット』を選択、 で も セ ー ヌ は 流 れ る 』な -

Ralph Waldo Emerson and Thomas Carlyle on Slavery

B093509 1 Examination Number: B093509 Title of work: Ralph Waldo Emerson and Thomas Carlyle on Slavery: Transatlantic Dissentions and Philosophical Connections Programme Name: MSc United States Literature Graduate School of Literatures, Languages & Cultures University of Edinburgh Word count: 15 000 Thomas Carlyle (1854) Ralph Waldo Emerson (1857) Source: archive.org/stream/pastandpresent06carlgoog#page/n10/mode/2up Source: ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/e/emerson/ralph_waldo/portrait.jpg B093509 2 Ralph Waldo Emerson and Thomas Carlyle on Slavery: Transatlantic Dissentions and Philosophical Connections Table of Contents Introduction 3 Chapter One: On Slavery and Labor: Racist Characterizations and 7 Economic Justifications Chapter Two On Democracy and Government: Ruling Elites and 21 Moral Diptychs Chapter Three On War and Abolition: Transoceanic Tensions and 35 Amicable Resolutions Conclusion 49 Bibliography 51 B093509 3 Introduction In his 1841 essay on “Friendship”, Ralph Waldo Emerson defined a “friend” as “a sort of paradox in nature” (348). Perhaps emulating that paradoxical essence, Emerson’s essay was pervaded with constant contradictions: while reiterating his belief in the “absolute insulation of man” (353), Emerson simultaneously depicted “friends” as those who “recognize the deep identity which beneath these disparities unites them” (“Friendship” 350). Relating back to the Platonic myth of recognition, by which one’s soul recognizes what it had previously seen and forgotten, Emerson defined a friend as that “Other” in which one is able to perceive oneself. As Johannes Voelz argued in Transcendental Resistance, “for Emerson, friendship … is a relationship from which we want to extract identity. Friendship is a relationship from which we seek recognition” (137). Indeed, Emerson was mostly concerned with what he called “high friendship” (“Friendship” 350) - an abstract ideality, which inevitably creates “a tension between potentiality and actuality” (Voelz 136). -

Tocqueville and Lower Canadian Educational Networks

Encounters on Education Volume 7, Fall 2006 pp. 113 - 130 Tocqueville and Lower Canadian Educational Networks Bruce Curtis Sociology and Anthropology, Carleton University, Canada ABSTRACT Educational history is commonly written as the history of institutions, pedagogical practices or individual educators. This article takes the trans-Atlantic networks of men involved in liberal political and educational reform in the early decades of the nineteenth century as its unit of analysis. In keeping with the author’s interest in education and politics in the British North American colony of Lower Canada, the network is anchored on the person of Alexis de Tocqueville, who visited the colony in 1831. De Tocqueville’s more or less direct connections to many of the men involved in colonial Canadian educational politics are detailed. Key words: de Tocqueville, liberalism, educational networks, monitorial schooling. RESUMEN La historia educativa se escribe comúnmente como la historia de las instituciones, de las prácticas pedagógicas o de los educadores individuales. Este artículo toma, como unidad de análisis, las redes transatlánticas formadas por hombres implicados en las reformas liberales políticas y educativas durante las primeras décadas del siglo XIX. En sintonía con el interés del autor en la educación y la política en la colonia Británico Norteamericana de Lower Canadá, la red se apoya en la persona de Alexis de Tocqueville, que visitó la colonia en 1831. Las relaciones de Tocqueville, más o menos directas, con muchos de los hombres implicados en política educativa del Canadá colonial son detalladas en este trabajo. Descriptores: DeTocqueville, Liberalismo, Redes educativas, Enseñanza monitorizada. RÉSUMÉ L’histoire de l’éducation est ordinairement écrite comme histoire des institutions, des pratiques pédagogiques ou d’éducateurs particuliers. -

Verse in Fraser's Magazine

Curran Index - Table of Contents Listing Fraser's Magazine For a general introduction to Fraser's Magazine see the Wellesley Index, Volume II, pages 303-521. Poetry was not included in the original Wellesley Index, an absence lamented by Linda Hughes in her influential article, "What the Wellesley Index Left Out: Why Poetry Matters to Periodical Studies," Victorian Periodicals Review, 40 (2007), 91-125. As Professor Hughes notes, Eileen Curran was the first to attempt to remedy this situation in “Verse in Bentley’s Miscellany vols. 1-36,” VPR 32 (1999), 103-159. As one part of a wider effort on the part of several scholars to fill these gaps in Victorian periodical bibliography and attribution, the Curran Index includes a listing of verse published in Fraser's Magazine from 1831 to 1854. EDITORS: Correct typo, 2:315, 1st line under this heading: Maginn, if he was editor, held the office from February 1830, the first issue, not from 1800. [12/07] Volume 1, Feb 1830 FM 3a, A Scene from the Deluge (from the German of Gesner), 24-27, John Abraham Heraud. Signed. Verse. (03/15) FM 4a, The Standard-Bearer -- A Ballad from the Spanish, 38-39, John Gibson Lockhart. possib. Attributed by Mackenzie in introduction to Fraserian Papers Vol I; see Thrall, Rebellious Fraser: 287 Verse. (03/15) FM 4b, From the Arabic, 39, Unknown. Verse. (03/15) FM 5a, Posthumous Renown, 44-45, Unknown. Verse. (03/15) FM 6a, The Fallen Chief (Translated from the Arabic), 54-56, Unknown. Verse. (03/15) Volume 1, Mar 1830 FM 16b, A Hard Hit for a Damosell, 144, Unknown. -

LM Findlay in the French Revolution: a History

L. M. Findlay "Maternity must forth": The Poetics and Politics of Gender in Carlyle's French Revolution In The French Revolution: A History ( 1837), Thomas Carlyle made a remarkable contribution to the history of discourse and to the legiti mation and dissemination of the idea of history qua discourse.' This work, born from the ashes of his own earlier manuscript, an irrecover able Ur-text leading us back to its equally irrecoverable 'origins' in French society at the end of the eighteenth century, represents a radical departure from the traditions of historical narrative.2 The enigmas of continuity I discontinuity conveyed so powerfully by the events of the Revolution and its aftermath are explored by Carlyle in ways that re-constitute political convulsion as the rending and repair of language as cultural fabric, or. to use terms more post-structuralist than Carlyl ean, as the process of rupture/suture in the rhetoric of temporality.3 The French Revolution, at once parodic and poetic, provisional and peremptory, announces itself as intertextual, epigraphic play, before paying tribute to the dialogic imagination in a series of dramatic and reflective periods which resonate throughout the poetry and prose of the Victorian period. In writing what Francis Jeffrey considered "undoubtedly the most poetical history the world has ever seen- and the most moral also,"4 Carlyle created an incurably reflexive idiom of astonishing modernity. And an important feature of this modernity indeed, a feature that provides a salutary reminder of the inevitably relative, historically mediated modernity of the discourse of periods earlier than our own - is the employment of countless versions of human gender to characterize and to contain the phenomenon of revolution. -

Huguenot Merchants Settled in England 1644 Who Purchased Lincolnshire Estates in the 18Th Century, and Acquired Ayscough Estates by Marriage

List of Parliamentary Families 51 Boucherett Origins: Huguenot merchants settled in England 1644 who purchased Lincolnshire estates in the 18th century, and acquired Ayscough estates by marriage. 1. Ayscough Boucherett – Great Grimsby 1796-1803 Seats: Stallingborough Hall, Lincolnshire (acq. by mar. c. 1700, sales from 1789, demolished first half 19th c.); Willingham Hall (House), Lincolnshire (acq. 18th c., built 1790, demolished c. 1962) Estates: Bateman 5834 (E) 7823; wealth in 1905 £38,500. Notes: Family extinct 1905 upon the death of Jessie Boucherett (in ODNB). BABINGTON Origins: Landowners at Bavington, Northumberland by 1274. William Babington had a spectacular legal career, Chief Justice of Common Pleas 1423-36. (Payling, Political Society in Lancastrian England, 36-39) Five MPs between 1399 and 1536, several kts of the shire. 1. Matthew Babington – Leicestershire 1660 2. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1685-87 1689-90 3. Philip Babington – Berwick-on-Tweed 1689-90 4. Thomas Babington – Leicester 1800-18 Seat: Rothley Temple (Temple Hall), Leicestershire (medieval, purch. c. 1550 and add. 1565, sold 1845, remod. later 19th c., hotel) Estates: Worth £2,000 pa in 1776. Notes: Four members of the family in ODNB. BACON [Frank] Bacon Origins: The first Bacon of note was son of a sheepreeve, although ancestors were recorded as early as 1286. He was a lawyer, MP 1542, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal 1558. Estates were purchased at the Dissolution. His brother was a London merchant. Eldest son created the first baronet 1611. Younger son Lord Chancellor 1618, created a viscount 1621. Eight further MPs in the 16th and 17th centuries, including kts of the shire for Norfolk and Suffolk.