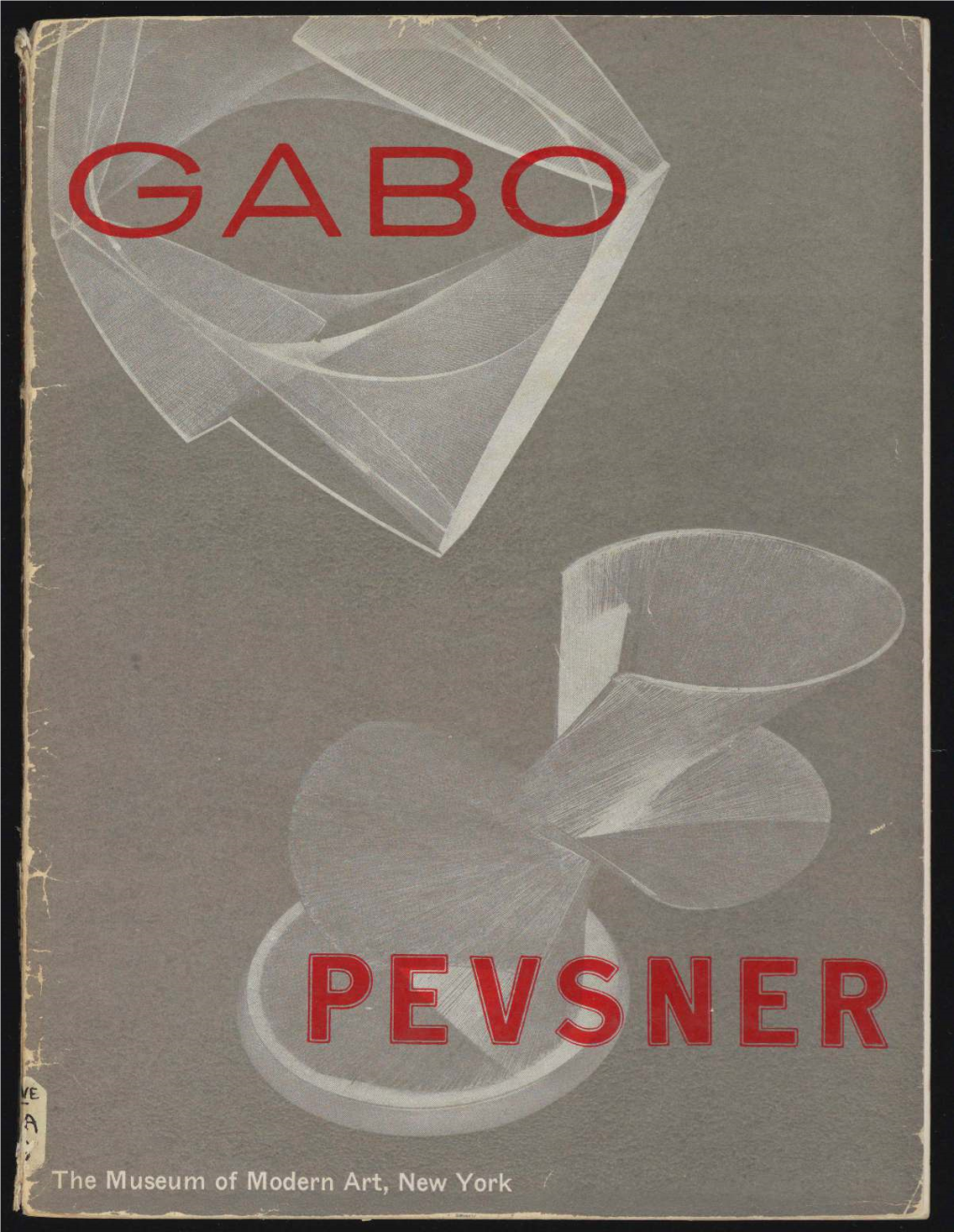

N a U M GABO

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(312) 443-3625 [email protected] [email protected]

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE January 14, 2013 MEDIA CONTACTS: Erin Hogan Chai Lee (312) 443-3664 (312) 443-3625 [email protected] [email protected] THE ART INSTITUTE HONORS 100-YEAR RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PICASSO AND CHICAGO WITH LANDMARK MUSEUM–WIDE CELEBRATION First Large-Scale Picasso Exhibition Presented by the Art Institute in 30 Years Commemorates Centennial Anniversary of the Armory Show Picasso and Chicago on View Exclusively at the Art Institute February 20–May 12, 2013 Special Loans, Installations throughout Museum, and Programs Enhance Presentation This winter, the Art Institute of Chicago celebrates the unique relationship between Chicago and one of the preeminent artists of the 20th century—Pablo Picasso—with special presentations, singular paintings on loan from the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and programs throughout the museum befitting the artist’s unparalleled range and influence. The centerpiece of this celebration is the major exhibition Picasso and Chicago, on view from February 20 through May 12, 2013 in the Art Institute’s Regenstein Hall, which features more than 250 works selected from the museum’s own exceptional holdings and from private collections throughout Chicago. Representing Picasso’s innovations in nearly every media—paintings, sculpture, prints, drawings, and ceramics—the works not only tell the story of Picasso’s artistic development but also the city’s great interest in and support for the artist since the Armory Show of 1913, a signal event in the history of modern art. BMO Harris is the Lead Corporate Sponsor of Picasso and Chicago. "As Lead Corporate Sponsor of Picasso and Chicago, and a bank deeply rooted in the Chicago community, we're pleased to support an exhibition highlighting the historic works of such a monumental artist while showcasing the artistic influence of the great city of Chicago," said Judy Rice, SVP Community Affairs & Government Relations, BMO Harris Bank. -

Exhibition of the Arthur Jerome Eddy Collection of Modern Paintings and Sculpture Source: Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago (1907-1951), Vol

The Art Institute of Chicago Exhibition of the Arthur Jerome Eddy Collection of Modern Paintings and Sculpture Source: Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago (1907-1951), Vol. 25, No. 9, Part II (Dec., 1931), pp. 1-31 Published by: The Art Institute of Chicago Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4103685 Accessed: 05-03-2019 18:14 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms The Art Institute of Chicago is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago (1907-1951) This content downloaded from 198.40.29.65 on Tue, 05 Mar 2019 18:14:34 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms EXHIBITION OF THE ARTHUR JEROME EDDY COLLECTION OF MODERN PAINTINGS AND SCULPTURE ARTHUR JEROME EDDY BY RODIN THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO DECEMBER 22, 1931, TO JANUARY 17, 1932 Part II of The Bulletin of The Art Institute of Chicago, Volume XXV, No. 9, December, 1931 This content downloaded from 198.40.29.65 on Tue, 05 Mar 2019 18:14:34 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms No. 19. -

Культура І Мистецтво Великої Британії Culture and Art of Great Britain

НАЦІОНАЛЬНА АКАДЕМІЯ ПЕДАГОГІЧНИХ НАУК УКРАЇНИ ІНСТИТУТ ПЕДАГОГІКИ Т.К. Полонська КУЛЬТУРА І МИСТЕЦТВО ВЕЛИКОЇ БРИТАНІЇ CULTURE AND ART OF GREAT BRITAIN Навчальний посібник елективного курсу з англійської мови для учнів старших класів профільної школи Київ Видавничий дім «Сам» 2017 УДК 811.111+930.85(410)](076.6) П 19 Рекомендовано до друку вченою радою Інституту педагогіки НАПН України (протокол №11 від 08.12.2016 року) Схвалено для використання у загальноосвітніх навчальних закладах (лист ДНУ «Інститут модернізації змісту освіти». №21.1/12 -Г-233 від 15.06.2017 року) Рецензенти: Олена Ігорівна Локшина – доктор педагогічних наук, професор, завідувачка відділу порівняльної педагогіки Інституту педагогіки НАПН України; Світлана Володимирівна Соколовська – кандидат педагогічних наук, доцент, заступник декана з науково- методичної та навчальної роботи факультету права і міжнародних відносин Київського університету імені Бориса Грінченка; Галина Василівна Степанчук – учителька англійської мови Навчально-виховного комплексу «Нововолинська спеціалізована школа І–ІІІ ступенів №1 – колегіум» Нововолинської міської ради Волинської області. Культура і мистецтво Великої Британії : навчальний посібник елективного курсу з англійської мови для учнів старших класів профільної школи / Т. К. Полонська. – К. : Видавничий дім «Сам», 2017. – 96 с. ISBN Навчальний посібник є основним засобом оволодіння учнями старшої школи змістом англомовного елективного курсу «Культура і мистецтво Великої Британії». Створення посібника сприятиме подальшому розвиткові у -

Recording of Marcel Duchamp’S Armory Show

Recording of Marcel Duchamp’s Armory Show Lecture, 1963 [The following is the transcript of the talk Marcel Duchamp (Fig. 1A, 1B)gave on February 17th, 1963, on the occasion of the opening ceremonies of the 50th anniversary retrospective of the 1913 Armory Show (Munson-Williams-Procter Institute, Utica, NY, February 17th – March 31st; Armory of the 69th Regiment, NY, April 6th – 28th) Mr. Richard N. Miller was in attendance that day taping the Utica lecture. Its total length is 48:08. The following transcription by Taylor M. Stapleton of this previously unknown recording is published inTout-Fait for the first time.] click to enlarge Figure 1A Marcel Duchamp in Utica at the opening of “The Armory Show-50th Anniversary Exhibition, 2/17/1963″ Figure 1B Marcel Duchamp at the entrance of the th50 anniversary exhibition of the Armory Show, NY, April 1963, Photo: Michel Sanouillet Announcer: I present to you Marcel Duchamp. (Applause) Marcel Duchamp: (aside) It’s OK now, is it? Is it done? Can you hear me? Can you hear me now? Yes, I think so. I’ll have to put my glasses on. As you all know (feedback noise). My God. (laughter.)As you all know, the Armory Show was opened on February 17th, 1913, fifty years ago, to the day (Fig. 2A, 2B). As a result of this event, it is rewarding to realize that, in these last fifty years, the United States has collected, in its private collections and its museums, probably the greatest examples of modern art in the world today. It would be interesting, like in all revivals, to compare the reactions of the two different audiences, fifty years apart. -

Volume IV, Number 1, Spring 2010

THE H ERALD VOLUME IV, N UMBER 1 WINTER /S PRING 2010 ‘Angel at the OPEN Tomb’ Window EXAMINED Our examination of the windows in the Magdalene went to visit the tomb of the sanctuary continues with a look at the crucified Christ. Upon discovering that Tiffany window located on the south the stone had been rolled away from the side in the second bay from the rear. opening of the tomb, the women were Known as “The Angel at the Open greeted by an angel who said “Fear not Tomb,” it depicts the seminal moment ye: for I know that ye seek Jesus, who in the history of Christianity when was crucified. He is not here: for He is Christ’s resurrection is first revealed to risen, as He said.” (Matthew 28:5) his followers. The overall scene depicts the angel The window is a memorial to Charles figure at left and the open tomb at right. H. Fargo, and was given by his three The landscape is lush, with a field of sons. Fargo was born in Tyringham, lilies in the foreground and hills beyond. Mass., in 1824 and came to Chicago in From an artistic standpoint, the window 1856 where he established himself in contains fine examples of the various the boot and shoe manufacturing types of glass developed by Tiffany. business. Although he had virtually no The angel figure displays milky white resources when first arriving in drapery glass and beautifully executed Chicago, he built up a house which feather glass, with fine ridges giving a eventually did a business of more than three-dimensional quality. -

Modern Masters from European and American Collections the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1940

Modern masters from European and American collections the Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1940 Author Museum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.) Date 1940 Publisher [publisher not identified] Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2796 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art ARCH I VE MMA97 c--/ TTBRARY museum r vvoCVv-RNART q* -«=ive<? I [ I [ I [ I H II ii M M II SP'i.v HBHHH r» MODERN FROM EUROPEANAND AMERICANCOLLECTIONS THE MUSEUMOF MODERNART, NEWYORK, 1940 MASTER S /\y cU \ A t £<?Y-£ kMfit V LENDERS TO THE EXHIBITION Mr. Stephen C. Clark, New York; Mr. Marcel Fleischmann, Zurich; Mr. Rene Gaffe, Brussels; Mr. A. Conger Goodyear, New York; Dr. and Mrs. David M. Levy, New York; The Lewisohn Collection, New York; Miss Ann Resor, New York; Mr. Edward G. Robinson, Beverly Hills; Miss Sally Ryan, London; Mr. John Hay Whitney, New York; Miss Gertrude B. Whittemore, Naugatuck, Connecticut; The Ferargil Galleries, New York; Wildenstein & Company, Inc., New York; The Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, New York; The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia; Phillips Memorial Gallery, Washington. TRUSTEES OF THE MUSEUM Stephen C. Clark, Chairman of the Board; John Hay Whitney, 1st Vice-Chairman; Samuel A. Lewisohn, 2nd Vice-Chairman; Nelson A. Rockefeller, President; Alfred H. Barr, Jr., Vice-President; John E. Abbott, Vice- President; Mrs. John S. Sheppard, Treasurer; Mrs. Robert Woods Bliss, Mrs. -

Yearbook02chic.Pdf

41 *( ^^Wk. _ f. CHICAGO LITERARY CLUB 1695-56 CHICAGO LITERARY CLUB YEAR-BOOK FOR 1895-96 Officer* for 1895-96 President. JOHN HENRY BARROWS. Vice-Presidents. FRANK H. SCOTT, HENRY S. BOUTELL, JAMES A. HUNT. Corresponding Secretary. DANIEL GOODWIN. Recording Secretary and Treasurer. FREDERICK W. GOOKIN. The above officers constitute the Board of Directors. Committees On Officers and Members. FRANK H. SCOTT, Chairman. ALLEN B. POND, ARTHUR D. WHEELER, THOMAS D. MARSTON, GEORGE L. PADDOCK. On Arrangements and Exercises. HENRY S. BOUTELL,C/tairman. EMILIUS C. DUDLEY, CHARLES G. FULLER, EDWARD O. BROWN, SIGMUND ZEISLER. On Rooms and Finance. JAMES A. HUNT, Chairman. WILLIAM R. STIRLING, JOHN H. HAMLINE, GEORGE H. HOLT, JAMES J. WAIT. On Publications. LEWIS H. BOUTELL, Chairman. FRANKLIN H. HEAD, CLARENCE A. BURLEY. Literarp Club Founded March 13, 1874 Incorporated July 10, 1886 ROBERT COLLYER, 1874-75 CHARLES B. LAWRENCE, 1875-76 HOSMER A. JOHNSON, 1876-77 DANIEL L. SHOREY, 1877-78 EDWARD G. MASON, . 1878-79 WILLIAM F. POOLE, 1879-80 BROOKE HERFORD, i 880-8 i EDWIN C. LARNED, 1881-82 GEORGE ROWLAND, . 1882-83 HENRY A. HUNTINGTON, 1883-84 CHARLES GILMAN SMITH, 1884-85 JAMES S. NORTON, 1885-86 ALEXANDER C. McCLURG, 1886-87 GEORGE C. NOYES, 1887-88 JAMES L. HIGH, . 1888-89 JAMES NEVINS HYDE, 1889-90 FRANKLIN H. HEAD, . 1890-91 CLINTON LOCKE, . 1891-92 LEWIS H. BOUTELL, . 1892-93 HORATIO L. WAIT, 1893-94 WILLIAM ELIOT FURNESS, 1894-95 JOHN HENRY BARROWS, 1895-96 Besfoent George E. Adams, Eliphalet W. Blatchford, Joseph Adams, Louis J. Block, Owen F. -

Kolokytha, Chara (2016) Formalism and Ideology in 20Th Century Art: Cahiers D’Art, Magazine, Gallery, and Publishing House (1926-1960)

Citation: Kolokytha, Chara (2016) Formalism and Ideology in 20th century Art: Cahiers d’Art, magazine, gallery, and publishing house (1926-1960). Doctoral thesis, Northumbria University. This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/32310/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/policies.html Formalism and Ideology in 20 th century Art: Cahiers d’Art, magazine, gallery, and publishing house (1926-1960) Chara Kolokytha Ph.D School of Arts and Social Sciences Northumbria University 2016 Declaration I declare that the work contained in this thesis has not been submitted for any other award and that it is all my own work. I also confirm that this work fully acknowledges opinions, ideas and contributions from the work of others. Ethical clearance for the research presented in this thesis is not required. -

A Living Tradition: the Winterbothams and Their Legacy Author(S): Lyn Delliquadri Source: Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies, Vol

The Art Institute of Chicago A Living Tradition: The Winterbothams and Their Legacy Author(s): Lyn Delliquadri Source: Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies, Vol. 20, No. 2, The Joseph Winterbotham Collection at The Art Institute of Chicago (1994), pp. 102-110 Published by: The Art Institute of Chicago Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4112959 . Accessed: 27/03/2014 16:47 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Art Institute of Chicago is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 198.40.29.65 on Thu, 27 Mar 2014 16:47:27 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions A Living Tradition: The Winterbothamsand Their Legacy LYN DELLIQUADRI The Art Institute of Chicago PA U L GA U G U I N. Portraitof a Womanin front of a Still Life by Cezanne, 1890 (pp. 128-29). This content downloaded from 198.40.29.65 on Thu, 27 Mar 2014 16:47:27 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions y the less thana centuryafter its founding, tured his fancy, and he enjoyed frequent travel there, 1920s, Chicago had been transformed from a prairie sending back photographsof himself stepping into Vene- swampland to an exuberant industrial and cul- tian gondolas and browsing in Parisianquarters. -

Newsletter & Review

NEWSLETTER & REVIEW Volume 59 z No. 2 Fall z Winter 2016 “Intrigued by the Cubist” Cather in translation Paul’s Pittsburgh: Inside “Denny & Carson’s” Willa Cather NEWSLETTER & REVIEW Volume 59 z No. 2 | Fall z Winter 2016 2 9 13 20 CONTENTS 1 Letters from the Executive Director and the President 13 Religiosa, Provinciale, Modernista: The Early Reception of Willa Cather in Italy 2 “Intrigued by the Cubist”: Cather, Sergeant, and Caterina Bernardini Auguste Chabaud Diane Prenatt 20 Willa Cather and Her Works in Romania Monica Manolachi 9 News from the Pittsburgh Seminar: Inside “Denny & Carson’s” 26 “Steel of Damascus”: Iron, Steel, and Marian Forrester Timothy Bintrim and James A. Jaap Emily J. Rau On the cover: Le Laboureur (The Plowman), Auguste Chabaud, 1912. Letter from collection of Cather materials. Plans took shape for a classroom, the Executive Director library, and study center to accommodate scholarly research and Ashley Olson educational programs. We made plans for an expanded bookstore, performer greenroom, and dressing rooms to enhance our Red Cloud Opera House. Our aspirations to create an interpretive Nine years ago this month, I came home to Red Cloud and museum exhibit were brought to life. And, in the midst of it all, interviewed for a position at the Willa Cather Foundation. I supporters near and far affirmed their belief in the project by listened attentively as executive director Betty Kort addressed making investments, both large and small. plans for the future. Among many things, she spoke of a Nine years later, the National Willa Cather Center is nearly historic downtown building known as the Moon Block. -

Flver MUSEUM of MODERN ART Jt WEST 53RD STREET, NEW YORK

si [HE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART JJ WEST 53rd STREET LEW YORK TELEPHONE: CIRCLE 5-8900 CABLES: MODERNART, NEW-YORK H NEWMEYER, PUBLICITY DIRECTOR SARA September 23, 1942, TO Art Editors City Editors Dear Sirs: You are invited to come or send a representative to PRESS PREVIEW of THE AMERICAS COOPERATE, prepared by the Museum at the request of the Coordinator of Inter- American Affairs and NEW ACQUISITIONS in Painting and Sculpture Tuesday, September 29 2 to 6 P.M. at the Museum of Modern Art 11 West 53 Street. The exhibitions will open to the public Wednesday, September 30. For further information please telephone me at Circle 5-8900. Sincerely yours, <A. //W-v^ Yu Sarah Newmeyer Publicity Director flVEr MUSEUM OF MODERN ART jt WEST 53RD STREET, NEW YORK fELKPHONE: CIRCLE 5-8900 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE NEW ACQUISITIONS IN PAINTING AND SCULPTURE ANNOUNCED BY MUSEUM OF MODERN ART On Wednesday, September 30, a small group of new acquisitions in European painting and sculpture will .be shown at the Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53 Street. This follows an exhibition of recent American accessions which closed on Sunday, September 27. Among the new acquisitions are works by three famous French artists, Degas, Derain and Berard; by an Italian, Modigllanl, who did his principal work in France; and by the ex-German, Eric Isenburger, and the Palestinian, Reuven Rubin, both of whom are now in the United States. A sculpture and a drawing by Jacques Lipchitz, now living in the United States, complete the group. The Modigliani painting Bride and Groom has been given by Frederic Clay Bartlett, noted collector and patron of art, who is an Honorary Trustee of the Museum of Modern Art. -

Commerce, Little Magazines and Modernity: New York, 1915-1922

Commerce, Little Magazines and Modernity: New York, 1915-1922 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, to be awarded by the University of De Montfort, Leicester Victoria Kingham University of De Montfort December 2009 Acknowledgements This PhD would have been impossible without the help of all the following people and organisations, and I would like to express heartfelt thanks to everyone here for their support for this work and for their continued belief in my work, and to all the institutions which have generously supported me financially. Birkbeck College, University of London Dr. Rebecca Beasley, Dr. Robert Inglesfield, Dr. Carol White. University of Cambridge Dr. Sarah Cain, Dr. Jean Chothia, Prof. Sarah Annes Brown, Dr. Eric White. De Montfort University, Leicester Prof. Andrew Thacker, Prof. Heidi MacPherson, Prof. Peter Brooker, Dr. Deborah Cartmell, Federico Meschini. Funding Institutions Birkbeck College, University of London; The Arts and Humanities Research Council; The British Association for American Studies; The Centre for Textual Studies, Modernist Magazines Project, and Research fund, De Montfort University. Friends and Family Richard Bell, John Allum, Peter Winnick, John Lynch, Rachel Holland, Philippa Holland, Adam Holland, Lucille and Lionel Holdsworth. 2 Abstract This thesis examines the theme of commerce in four magazines of literature and the arts, all published in New York between 1915 and 1922. The magazines are The Seven Arts (1916-1917), 291 (1915-1916), The Soil (1916-1917), and The Pagan (1916-1922). The division between art and commerce is addressed in the text of all four, in a variety of different ways, and the results of that supposed division are explored for each magazine.