RITCHEL-THESIS.Pdf (3.132Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

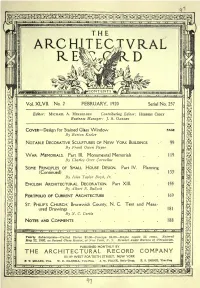

February 1920

ii^^ir^?!'**i r*sjv^c ^5^! J^^M?^J' 'ir ^M/*^j?r' ?'ij?^'''*vv'' *'"'**'''' '!'<' v!' '*' *w> r ''iw*i'' g;:g5:&s^ ' >i XA. -*" **' r7 i* " ^ , n it A*.., XE ETT XX " " tr ft ff. j 3ty -yj ri; ^JMilMMIIIIilllilllllMliii^llllll'rimECIIIimilffl^ ra THE lot ARC HIT EC FLE is iiiiiBiicraiiiEyiiKii! Vol. XLVII. No. 2 FEBRUARY, 1920 Serial No. 257 Editor: MICHAEL A. MIKKELSEN Contributing Editor: HERBERT CROLY Business Manager: ]. A. OAKLEY COVER Design for Stained Glass Window FAGS By Burton Keeler ' NOTABLE DECORATIVE SCULPTURES OF NEW YOKK BUILDINGS _/*' 99 .fiy Frank Owen Payne WAK MEMORIALS. Part III. Monumental Memorials . 119 By Charles Over Cornelius SOME PRINCIPLES OF SMALL HOUSE DESIGN. Part IV. Planning (Continued) .... .133 By John Taylor Boyd, Jr. ENGLISH ARCHITECTURAL DECORATION. Part XIII. 155 By Albert E. Bullock PORTFOLIO OF CURRENT ARCHITECTURE . .169 ST. PHILIP'S CHURCH, Brunswick County, N. C. Text and Meas^ ured Drawings . .181 By N. C. Curtis NOTES AND COMMENTS . .188 Yearly Subscription United States $3.00 Foreign $4.00 Single copies 35 cents. Entered May 22, 1902, as Second Class Matter, at New York, N. Y. Member Audit Bureau of Circulation. PUBLISHED MONTHLY BY THE ARCHITECTURAL RECORD COMPANY 115-119 FOFvIlt I i I IStt I, NEWINCW YORKTUKN WEST FORTIETHM STREET, H v>^ E. S. M tlli . T. MILLER, Pres. W. D. HADSELL, Vice-Pres. J. W. FRANK, Sec'y-Treas. DODGE. Vice-Pre* ' "ri ti i~f n : ..YY '...:.. ri ..rr.. m. JT i:c..."fl ; TY tn _.puc_. ,;? ,v^ Trrr.^yjL...^ff. S**^ f rf < ; ?SIV5?'Mr ^7"jC^ te :';T:ii!5ft^'^"*TiS t ; J%WlSjl^*o'*<JWii*^'J"-i!*^-^^**-*''*''^^ *,iiMi.^i;*'*iA4> i.*-Mt^*i; \**2*?STO I ASTOR DOORS OF TRINITY CHURCH. -

Dubrovnik Manuscripts and Fragments Written In

Rozana Vojvoda DALMATIAN ILLUMINATED MANUSCRIPTS WRITTEN IN BENEVENTAN SCRIPT AND BENEDICTINE SCRIPTORIA IN ZADAR, DUBROVNIK AND TROGIR PhD Dissertation in Medieval Studies (Supervisor: Béla Zsolt Szakács) Department of Medieval Studies Central European University BUDAPEST April 2011 CEU eTD Collection TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 7 1.1. Studies of Beneventan script and accompanying illuminations: examples from North America, Canada, Italy, former Yugoslavia and Croatia .................................................................................. 7 1.2. Basic information on the Beneventan script - duration and geographical boundaries of the usage of the script, the origin and the development of the script, the Monte Cassino and Bari type of Beneventan script, dating the Beneventan manuscripts ................................................................... 15 1.3. The Beneventan script in Dalmatia - questions regarding the way the script was transmitted from Italy to Dalmatia ............................................................................................................................ 21 1.4. Dalmatian Benedictine scriptoria and the illumination of Dalmatian manuscripts written in Beneventan script – a proposed methodology for new research into the subject .............................. 24 2. ZADAR MANUSCRIPTS AND FRAGMENTS WRITTEN IN BENEVENTAN SCRIPT ............ 28 2.1. Introduction -

Impressionist and Modern Art Introduction Art Learning Resource – Impressionist and Modern Art

art learning resource – impressionist and modern art Introduction art learning resource – impressionist and modern art This resource will support visits to the Impressionist and Modern Art galleries at National Museum Cardiff and has been written to help teachers and other group leaders plan a successful visit. These galleries mostly show works of art from 1840s France to 1940s Britain. Each gallery has a theme and displays a range of paintings, drawings, sculpture and applied art. Booking a visit Learning Office – for bookings and general enquires Tel: 029 2057 3240 Email: [email protected] All groups, whether visiting independently or on a museum-led visit, must book in advance. Gallery talks for all key stages are available on selected dates each term. They last about 40 minutes for a maximum of 30 pupils. A museum-led session could be followed by a teacher-led session where pupils draw and make notes in their sketchbooks. Please bring your own materials. The information in this pack enables you to run your own teacher-led session and has information about key works of art and questions which will encourage your pupils to respond to those works. Art Collections Online Many of the works here and others from the Museum’s collection feature on the Museum’s web site within a section called Art Collections Online. This can be found under ‘explore our collections’ at www.museumwales.ac.uk/en/art/ online/ and includes information and details about the location of the work. You could use this to look at enlarged images of paintings on your interactive whiteboard. -

Cubism in America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications Sheldon Museum of Art 1985 Cubism in America Donald Bartlett Doe Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs Part of the Art and Design Commons Doe, Donald Bartlett, "Cubism in America" (1985). Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications. 19. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sheldon Museum of Art at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. RESOURCE SERIES CUBISM IN SHELDON MEMORIAL ART GALLERY AMERICA Resource/Reservoir is part of Sheldon's on-going Resource Exhibition Series. Resource/Reservoir explores various aspects of the Gallery's permanent collection. The Resource Series is supported in part by grants from the National Endowment for the Arts. A portion of the Gallery's general operating funds for this fiscal year has been provided through a grant from the Institute of Museum Services, a federal agency that offers general operating support to the nation's museums. Henry Fitch Taylor Cubis t Still Life, c. 19 14, oil on canvas Cubism in America .".. As a style, Cubism constitutes the single effort which began in 1907. Their develop most important revolution in the history of ment of what came to be called Cubism art since the second and third decades of by a hostile critic who took the word from a the 15th century and the beginnings of the skeptical Matisse-can, in very reduced Renaissance. -

Vladimir-Peter-Goss-The-Beginnings

Vladimir Peter Goss THE BEGINNINGS OF CROATIAN ART Published by Ibis grafika d.o.o. IV. Ravnice 25 Zagreb, Croatia Editor Krešimir Krnic This electronic edition is published in October 2020. This is PDF rendering of epub edition of the same book. ISBN 978-953-7997-97-7 VLADIMIR PETER GOSS THE BEGINNINGS OF CROATIAN ART Zagreb 2020 Contents Author’s Preface ........................................................................................V What is “Croatia”? Space, spirit, nature, culture ....................................1 Rome in Illyricum – the first historical “Pre-Croatian” landscape ...11 Creativity in Croatian Space ..................................................................35 Branimir’s Croatia ...................................................................................75 Zvonimir’s Croatia .................................................................................137 Interlude of the 12th c. and the Croatia of Herceg Koloman ............165 Et in Arcadia Ego ...................................................................................231 The catastrophe of Turkish conquest ..................................................263 Croatia Rediviva ....................................................................................269 Forest City ..............................................................................................277 Literature ................................................................................................303 List of Illustrations ................................................................................324 -

The Emancipatory Potential of Karaman's Concept of “Peripheral Art”

The Emancipatory Potential of Karaman's Concept of "Peripheral Art”: Still Operative? Laris Borić University of Zadar, Croatia When viewed within its broader European context, the entire premodern Croatian architectural and artistic heritage is characterized by some atypical features. The traditional Eurocentric art-historical narrative follows regional and national paradigms, recognizing trails of political and cultural dominance that emit style and form from centers of power toward near and distant areas in what are usually seen as concentric circles. In the continental parts of Croatia those influences were mostly of a Central European nature, while on the Adriatic coastline there was a continuous flow of Italic influences. However, a cultural bipolarity developed when the long continuity of Roman civilization that extended in the eastern Adriatic communities throughout the medieval period was countered by that of the ninth- century Croatian kingdom whose cultural milieu would permeate that of the coastal Romanized towns. Such fusion of traditions, cultures, and collective experiences, which generated a peculiar genius loci at the confluence of the East and the West, later was dominated by Venice, while the Balkan hinterland was ruled by the Ottoman Empire. Early- to mid-twentieth-century art historians who adhered to fragmentary and nationally biased interpretation often saw eastern Adriatic medieval and early-modern art as a weakened provincial reflection of what was imported from Italian centers.1 Such writings were subsequently abused by pre-World War II politics as proof of a territorial claim by Italy to the whole Adriatic rim, sometimes even as an indication of Italian superiority over Slavic (Croatian and Slovenian) ethnicity or race. -

The Breakers/Cornelius Vanderbilt II House National Historic Landmark

__________ ______________ __-_____________-________________ -. ‘"I. *II.fl.* *%tØ*** *.‘" **.‘.i --II * y*’ * - *t_ I 9 - * ‘I teul eeA ‘4 I A I I I UNITED STATES IEPASTMENI OF THE INTERIOP ;‘u is NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Rhode Island .5 1 - COUNTY NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Newport INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER I DATE Type ii!! entries - Complete applicable SeCtions NAME -- OMMON - ... The Breakers AN 0/On HISTORIC: * Vanderbilt Corneiius..II Hcnise ftcOCAT!ON .1 ., * ./1..... H :H5.j_ .. H .O H.H/.H::: :- 51 RECT AND NUMBER: Ochre Point Avenue CITY OR TOWN: flewpcrt STATE COUNTY: - *[7m . CODE Rhode I3land, O2flhO Newport 005 -- CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE tn OWNERSHIP STATUS C/reck One TO THE PUBLIC El District iEj Building LI PubIC Public Acc1ui Si’on: LI Occupied Yes: 0 Restricted El Si to LI Structure Private LI 0 P roess Unoccupied LI Unre.trtcsed Er Oblect LI Both [3 Being Considered j Preservation work I. in progress LI No U PRESENT USE Check One or More as Appropriate LI Agriu Iturol LI 0 overn-ten? LI Pork [3 Transportation [3 Comments DC El C OrIImerC i ol [3 Hdju al [3 Pri vote Residence [3 Other SpocI’ I LI Educational [3 Miii tory [3 Religious - Entertainment Museum Scientific ‘I, LI --__ flAkE; S UWNIrRs Alice FHdik, Gladys raljlqt Peterson, Sylvia S. 5zapary, Nanine -I tltz, Gladys P.. thoras, Cornelia Uarter Roberts; Euaene B. R&erts, Jr. -1 S w STREET ANd NLIMBER: Lu The Breakers, Ochre Point Avenue CITY ** STATE: tjfl OR TOWN: - --.*** CODE Newport Rhode Island, 028b0 lili iLocATIoNcrLEGALDEsRIpTwN 7COURTHOUSr, REGISTRY OF DEEDS. -

The Book Art in Croatia Exhibition Catalogue

Book Art in Croatia BOOK ART IN CROATIA National and University Library in Zagreb, Zagreb, 2018 Contents Foreword / 4 Centuries of Book Art in Croatia / 5 Catalogue / 21 Foreword The National and University Library in Croatia, with the aim to present and promote the Croatian cultural heritage has prepared the exhibition Book Art in Croatia. The exhibition gives a historical view of book preparation and design in Croatia from the Middle Ages to the present day. It includes manuscript and printed books on different topics and themes, from mediaeval evangelistaries and missals to contemporary illustrated editions, print portfolios and artists’ books. Featured are the items that represent the best samples of artistic book design in Croatia with regard to their graphic design and harmonious relationship between the visual and graphic layout and content. The author of the exhibition is art historian Milan Pelc, who selected 60 items for presentation on panels. In addition to the introductory essay, the publication contains the catalogue of items with short descriptions. 4 Milan Pelc CENTURIES OF BOOK ART IN CROATIA Introduction Book art, a constituent part of written culture and Croatian cultural heritage as a whole, is ex- ceptionally rich and diverse. This essay does not pretend to describe it in its entirety. Its goal is to shed light on some (key) moments in its complex historical development and point to its most important specificities. The essay does not pertain to entire Croatian literary heritage, but only to the part created on the historical Croatian territory and created by the Croats. Namely, with regard to its origins, the Croatian literary heritage can be divided into three big groups. -

French Art, Classic and Contemporary, Painting and Sculpture

NYPL RESEARCH LIBRARIES 3 3433 08191162 4 Virt-*'.', FRENCH ART THE HEW YORK PDBLIC LIB4^ARY ASTOK, LENOX Tli-DEN FOUNDATIONS / / "W Y( J SCRIB] 1 90J NG THE DAWN / FRENCH ART CLASSIC AND CONTEMPORARY PAINTING AND SCULPTURE BY W. C. BROWNELL NEW AND ENLARGED EDITION WITH FORTY-EIGHT ILLUSTRATIONS NEW YORK CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS 1901 COPYRIGHT, 1892, 1901, BY CHARLES SCRIBNEr's SONS PUBLISHED OCTOBER, 1901 THE NEW r, yc>^Y "y BUG LIBRARY ' ' i "» —f A S< » , TILBSN Pi»-JNBATIO«« D. B. UPDIKE, THE MERRYMOUNT PRESS, BOSTON TO AUGUSTE RODIN Advantage has been taken of the present ilkistrated edition of this book to add a chapter on "Rodin and the Institute," in which the progress of what ten years ago was altogether a "new movement in sculpture," is further considered. Except in sculpture, and in the sculpture of Rodin and that more or less directly in- fluenced by him, thei-e has been no new phase of French art developed within the decade — at least none important enough to impose other additions to the text of a work so general in character. CONTENTS I. CLASSIC PAINTING 1 I. CHARACTER AND ORIGIN II. CLAUDE AND POUSSIN III. LEBRUN AND LESUEUR IV. LOUIS QUINZE V. GREUZE AND CHARDIN VI. DAVID, INGRES, AND PRUDHON II. ROMANTIC PAINTING 39 I. ROMANTICISM II. GERICAULT AND DELACROIX III. THE FONTAINEBLEAU GROUP IV. THE ACADEMIC PAINTERS V. COUTURE, PUVIS DE CHAVANNES, AND REGNAULT III. REALISTIC PAINTING 75 I. REALISM II. COURBET AND BASTIEN-LEPAGE III. THE LANDSCAPE PAINTERS ; FROMENTIN AND GUILLAUMET IV. HISTORICAL AND PORTRAIT PAINTERS V. -

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice PUBLICATIONS COORDINATION: Dinah Berland EDITING & PRODUCTION COORDINATION: Corinne Lightweaver EDITORIAL CONSULTATION: Jo Hill COVER DESIGN: Jackie Gallagher-Lange PRODUCTION & PRINTING: Allen Press, Inc., Lawrence, Kansas SYMPOSIUM ORGANIZERS: Erma Hermens, Art History Institute of the University of Leiden Marja Peek, Central Research Laboratory for Objects of Art and Science, Amsterdam © 1995 by The J. Paul Getty Trust All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-89236-322-3 The Getty Conservation Institute is committed to the preservation of cultural heritage worldwide. The Institute seeks to advance scientiRc knowledge and professional practice and to raise public awareness of conservation. Through research, training, documentation, exchange of information, and ReId projects, the Institute addresses issues related to the conservation of museum objects and archival collections, archaeological monuments and sites, and historic bUildings and cities. The Institute is an operating program of the J. Paul Getty Trust. COVER ILLUSTRATION Gherardo Cibo, "Colchico," folio 17r of Herbarium, ca. 1570. Courtesy of the British Library. FRONTISPIECE Detail from Jan Baptiste Collaert, Color Olivi, 1566-1628. After Johannes Stradanus. Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum-Stichting, Amsterdam. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Historical painting techniques, materials, and studio practice : preprints of a symposium [held at] University of Leiden, the Netherlands, 26-29 June 1995/ edited by Arie Wallert, Erma Hermens, and Marja Peek. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-89236-322-3 (pbk.) 1. Painting-Techniques-Congresses. 2. Artists' materials- -Congresses. 3. Polychromy-Congresses. I. Wallert, Arie, 1950- II. Hermens, Erma, 1958- . III. Peek, Marja, 1961- ND1500.H57 1995 751' .09-dc20 95-9805 CIP Second printing 1996 iv Contents vii Foreword viii Preface 1 Leslie A. -

Memorinmotion

english memorInmotion pedagogical tool on culture of remembrance manual dvd second supplemented edition MemorInmotion Pedagogical Tool on Culture of Remembrance Second supplemented edition Manual DVD Sarajevo, 2016 Publication Title: Consultants: MemorInmotion - Pedagogical Tool on Culture of Suad Alić Remembrance Andrea Baotić Second supplemented edition Judith Brand Elma Hašimbegović Authors: Adis Hukanović Laura Boerhout Alma Mašić Ana Čigon Nerkez Opačin Bojana Dujković-Blagojević Christian Pfeifer Melisa Forić Soraja Zagić Senada Jusić Muhamed Kafedžić Muha Editor-in-chief: Larisa Kasumagić-Kafedžić Michele Parente Vjollca Krasniqi Nita Luci Project Coordinators: Nicolas Moll Michele Parente, forumZFD Michele Parente Melisa Forić, EUROCLIO HIP BiH Wouter Reitsema Laura Boerhout, Anne Frank House (Netherlands) Students of the PI Gymnasium Obala, Sarajevo CIP - Katalogizacija u publikaciji Nacionalna i univerzitetska biblioteka Bosne i Hercegovine, Sarajevo 791.5:725.94(497) MEMORLNMOTION : pedagogical tool on culture of remembrance : manual / [authors Melisa Forić ... [et al.] ; translators Lejla Efendić, Gordana Lonco]. - 2nd supplemented ed. - Sarajevo : Forum Ziviler Friedensdienste e.V. (forumZFD), 2016. - 101 str. : ilustr. ; 20 x 20 cm + [1] DVD Prijevod djela: Sjećanje u pokretu. - The authors: str. 93-96. - Bibliografija: str. 97-100 ISBN 978-9958-0399-6-6 1. Forić, Melisa COBISS.BH-ID 23297286 contents I. Manual 1.0. Introduction 1.1. Memorlnmotion - Pedagogical Tool on Culture of Remembrance 7 2.0. Essay: how to create an active culture of remembrance in our societies? 2.1. Challenging young people to reflect on monuments and their meaning 11 3.0. The pedagogical modules with lesson plans 3.1. Module I: Start-up 3.1.1. Lesson Plan 1: Who am I? 17 3.2. -

2425 Hermon Atkins Macneil, 1866

#2425 Hermon Atkins MacNeil, 1866-1947. Papers, [1896-l947J-1966. These additional papers include a letter from William Henry Fox, Secretary General of the U.S. Commission to the International Exposition of Art and History at Rome, Italy, in 1911, informing MacNeil that the King of Italy, Victor Emmanuel III, is interested in buying his statuette "Ai 'Primitive Chant", letters notifying MacNeil that he has been made an honorary member of the American Institute of Architects (1928) and a fellow of the AmRrican Numismatic Society (1935) and the National Sculpture Society (1946); letters of congratulation upon his marriage to Mrs. Cecelia W. Muench in 1946; an autobiographical sketch (20 pp. typescript carbon, 1943), certificates and citations from the National Academy of Design, the National Institute of Arts and letters, the Architectural League of New York, and the Disabled American Veterans of the World War, forty-eight photographs (1896+) mainly of the artist and his sculpture, newspaper clippings on his career, and miscellaneous printed items. Also, messages of condolence and formal tri butes sent to his widow (1947-1948), obituaries, and press reports (1957, 1966) concerning a memorial established for the artist. Correspondents include A. J. Barnouw, Emile Brunet, Jo Davidson, Carl Paul Jennewein, Leon Kroll, and many associates, relatives, and friends. £. 290 items. Maim! entry: Cross references to main entry: MacNeil, Hermon Atkins, 1866-1947. Barnouw, Adrian Jacob, 1877- Papers, [1896-l947J-1966. Brunet, Emile, 1899- Davidson, Jo, 1883-1951 Fox, William Henry Jennewein, Carl Paul, 1890- Kroll, Leon, 1884- Muench, Cecelia W Victor Emmanuel III, 1869-1947 See also detailed checklists on file in this folder.