106002 3951 1.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogue Pilot Film & Television Productions Ltd

productions 2020 Catalogue Pilot Film & Television Productions Ltd. is a leading international television production company with an outstanding reputation for producing and distributing innovative factual entertainment, history and travel led programmes. The company was set up by Ian Cross in 1988; and it is now one of the longest established independent production companies under continuous ownership in the United Kingdom. Pilot has produced over 500 hours of multi-genre programming covering subjects as diverse as history, food and sport. Its award winning Globe Trekker series, broadcast in over 20 countries, has a global audience of over 20 million. Pilot Productions has offices in London and Los Angeles. CONTENTS Mission Statement 3 In Production 4 New 6 Tough Series 8 Travelling in the 1970’s 10 Specials 11 Empire Builders 12 Ottomans vs Christians 14 History Specials 18 Historic Walks 20 Metropolis 21 Adventure Golf 22 Great Railway Journeys of Europe 23 The Story Of... Food 24 Bazaar 26 Globe Trekker Seasons 1-5 28 Globe Trekker Seasons 6-11 30 Globe Trekker Seasons 12-17 32 Globe Trekker Specials 34 Globe Trekker Around The World 36 Pilot Globe Guides 38 Destination Guides 40 Other Programmes 41 Short Form Content 42 DVDs and music CDs 44 Study Guides 48 Digital 50 Books 51 Contacts 52 Presenters 53 2 PILOT PRODUCTIONS 2020 MISSION STATEMENT Pilot Productions seeks to inspire and educate its audience by creating powerful television programming. We take pride in respecting and promoting social, environmental and personal change, whilst encouraging others to travel and discover the world. Pilot’s programmes have won more than 50 international awards, including six American Cable Ace awards. -

Remembering the Dearly Departed

www.ipohecho.com.my IPOH echoechoYour Community Newspaper FREE for collection from our office and selected outlets, on 1st & 16th of the month. 30 sen for delivery to your ISSUE JULY 1 - 16, 2009 PP 14252/10/2009(022651) house by news vendors within Perak. RM 1 prepaid postage for mailing within Malaysia, Singapore and Brunei. 77 NEWS NEW! Meander With Mindy and discover what’s new in different sections of Ipoh A SOCIETY IS IPOH READY FOR HIDDEN GEMS TO EMPOWER THE INTERNATIONAL OF IPOH MALAYS TOURIST? 3 GARDEN SOUTH 11 12 REMEMBERING THE DEARLY DEPARTED by FATHOL ZAMAN BUKHARI The Kamunting Christian Cemetery holds a record of sorts. It has the largest number of Australian servicemen and family members buried in Malaysia. All in all 65 members of the Australian Defence Forces were buried in graves all over the country. Out of this, 40 were interred at the Kamunting burial site, which is located next to the Taiping Tesco Hypermarket. They were casualties of the Malayan Emergency (1948 to 1960) and Con- frontation with Indonesia (1963 to 1966). continued on page 2 2 IPOH ECHO JULY 1 - 16, 2009 Your Community Newspaper A fitting service for the Aussie soldiers who gave their lives for our country or over two decades headstones. Members, Ffamilies and friends their families and guests of the fallen heroes have then adjourned to the been coming regularly Taiping New Club for to Ipoh and Taiping to refreshments. honour their loved ones. Some come on their own Busy Week for Veterans while others make their The veterans made journey in June to coincide full use of their one-week with the annual memorial stay in Ipoh by attending service at the God’s Little other memorial services Acre in Batu Gajah. -

Government Transformation Programme the Roadmap Diterbitkan Pada 28 Januari 2010

Government Transformation Programme The Roadmap Diterbitkan pada 28 Januari 2010 ©Hak cipta Unit Pengurusan Prestasi dan Pelaksanaan (PEMANDU), Jabatan Perdana Menteri Hak cipta terpelihara, tiada mana-mana bahagian daripada buku ini boleh diterbitkan semula, disimpan untuk pengeluaran atau ditukar kepada apa-apa bentuk dengan sebarang cara sekalipun tanpa izin daripada penerbit. Diterbit oleh: Unit Pengurusan Prestasi Dan Pelaksanaan (PEMANDU) Jabatan Perdana Menteri Aras 3, Blok Barat, Pusat Pentadbiran Kerajaan Persekutuan 62502 Putrajaya Tel: 03-8881 0128 Fax: 03-8881 0118 Email: [email protected] Laman Web: www.transformation.gov.my Dicetak oleh: Percetakan Nasional Malaysia Berhad (PNMB) Jalan Chan Sow Lin 50554 Kuala Lumpur Tel: 03-9236 6895 Fax: 03-9222 4773 Email: [email protected] Laman Web: www.printnasional.com.my Government Transformation Programme The Roadmap Foreword It is clear that Malaysia has achieved much as a young nation. We have made significant strides in eradicating hardcore poverty, we have developed a diversified economic base, increased the quality of life of the average citizen and created a progressive civil service which embraces change. But it is also clear that we face significant challenges to achieve the ambitious goals of Vision 2020, by the year 2020. I am confident that this Government Transformation Programme (GTP) Roadmap is what we need to help chart our path towards Vision 2020. It details a bold and unprecedented programme to begin to transform the Government and to renew the Government’s focus on delivering services to the rakyat. The scope of this GTP is broad, and will encompass every Ministry within government. -

MISC. HERITAGE NEWS –March to July 2017

MISC. HERITAGE NEWS –March to July 2017 What did we spot on the Sarawak and regional heritage scene in the last five months? SARAWAK Land clearing observed early March just uphill from the Bongkissam archaeological site, Santubong, raised alarm in the heritage-sensitive community because of the known archaeological potential of the area (for example, uphill from the shrine, partial excavations undertaken in the 1950s-60s at Bukit Maras revealed items related to the Indian Gupta tradition, tentatively dated 6 to 9th century). The land in question is earmarked for an extension of Santubong village. The bulldozing was later halted for a few days for Sarawak Museum archaeologists to undertake a rapid surface assessment, conclusion of which was that “there was no (…) artefact or any archaeological remains found on the SPK site” (Borneo Post). Greenlight was subsequently given by the Sarawak authorities to get on with the works. There were talks of relocating the shrine and, in the process, it appeared that the Bongkissam site had actually never been gazetted as a heritage site. In an e-statement, the Sarawak Heritage Society mentioned that it remained interrogative and called for due diligences rules in preventive archaeology on development sites for which there are presumptions of historical remains. Dr Charles Leh, Deputy Director of the Sarawak Museum Department mentioned an objective to make the Santubong Archaeological Park a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2020. (our Nov.2016-Feb.2017 Newsletter reported on this latter project “Extension project near Santubong shrine raises concerns” – Borneo Post, 22 March 2017 “Bongkissam shrine will be relocated” – Borneo post, 23 March 2017 “Gazette Bongkissam shrine as historical site” - Borneo Post. -

Labour Unrest in Malaya, 1934-1941

Title Labour unrest in Malaya, 1934-1941 Author(s) Tai, Yuen.; 戴淵 Tai, Y. [戴淵]. (1973). Labour unrest in Malaya, 1934-1941. Citation (Thesis). University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong SAR. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.5353/th_b3120344 Issued Date 1973 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10722/39263 The author retains all proprietary rights, (such as patent rights) Rights and the right to use in future works. UNIVERSITY OF HONG KONG FACULTY OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY A Thesis LABOUR UNREST IN MALAYA 1934-1941 Submitted by Tai Yuen In Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Master of Philosophy May 1973 ABSTRACT of thesis entitled "Labour Unrest in Malaya 1934-1941" submitted by Tai Yuen for the degree of Master of Philosophy at the University of Hong Kong in May 1973. ****** The period 1934-41 witnessed a tremendous upsurge of labour unrest in Malaya. Beginning with the skilled artisans in 1934, large numbers of labourers in almost all industries throughout Malaya were swept into the vortex of industrial conflict in the following years. Both the Chinese and the Indian labourers had learnt to combine against their employers for higher wages and better working conditions, and the strike weapon was constantly used to enforce their demands. As a result the workers managed to rise from the depths of the Great Depression and secure hitherto unknown improvement in working conditions. This was accompanied by an enormous growth in the strength of organized labour. In 1941 at least 178 workers' associations were in existence in Malaya, and over two-thirds of these were formed during 1934-41. -

Healthier Lifestyle Through Better Choices

YEO HIAP SENG LIMITED YEO HIAP SENG LIMITED Yeo Hiap Seng Limited (Company Registration No.: 195500138Z) 3 Senoko Way Singapore 758057 ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Tel: +65 6752 2122 | Fax: +65 6752 3122 www.yeos.com.sg Healthier Lifestyle Through Better Choices ANNUAL REPORT 2019 YEO HIAP SENG LIMITED Annual Report 2019 01 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chairman’s Statement 02 Financial Highlights 06 Corporate Information 07 Profile of the Board of Directors 08 Corporate Governance Report 13 Sustainability Report 40 Financial Statements 71 Statistics of Shareholdings 169 Notice of Annual General Meeting 171 Supplemental Information on Director Seeking Re-election 178 Supplemental Information on New Directors 181 Proxy Form Healthier Lifestyle Through Better Choices 02 , CHAIRMAN S STATEMENT DEAR SHAREHOLDERS, 80 per cent of Yeo’s beverage sales in Singapore are from healthier choice products, we will continue to work I am honoured and humbled to serve Yeo Hiap Seng closely with the regulators to ensure that we comply with Limited (“YHS” or the “Group”) as Chairman of the the new regulations and guidelines. In Cambodia, we Board. 2020 marks the 120th anniversary of Yeo’s, recorded a strong growth of 37% in sales as we worked a household name with a rich history in bringing closely with distribution partners to drive product visibility happiness to consumers with our quality and innovative and availability in the market. In China, we refreshed food and beverages of authentic Southeast Asian taste. our packaging and ran interactive QR code promotions I look forward to working with the team as we start a to increase engagement with our consumers and to new chapter of Yeo’s journey together, building on our drive sales. -

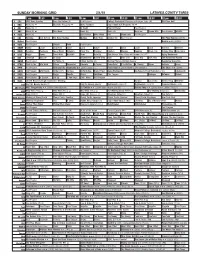

Sunday Morning Grid 2/1/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/1/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program College Basketball Michigan at Michigan State. (N) PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å Make Football Super Bowl XLIX Pregame (N) Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Ocean Mys. Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Winning Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Kids News Animal Sci Paid Program The Polar Express (2004) 13 MyNet Paid Program Bernie ››› (2011) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Atrévete 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Rick Steves’ Italy: Cities of Dreams (TVG) Å Aging Backwards 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki Doki (TVY) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly The Karate Kid Part III 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer República Deportiva 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Alvin and the Chipmunks ›› (2007) Jason Lee. -

Gustavus 2020 Brochure

singapore malaysia gustavus symphony orchestra gustavus jazz ensemble JANUARY 24 - FEBRUARY 8, 2020 13-night tour planned and produced by www.accentconcerts.com GUSTAVUS SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA & JAZZ ENSEMBLE singapore & malaysia Clockwise from top: Batu Caves; George Town seen from Penang Hill; Independence Square, Kuala Lumpur Friday, January 24 & Saturday, January 25 section of one of the city’s residential Mansion, and Market Street. Check into Overnight flights to Malaysia neighborhoods around the city that are the hotel and have dinner in a local closed to traffic after the workday ends in restaurant. (B,D) Sunday, January 26 order to allow for endless stalls of Welcome to Malaysia merchants selling produce street food, Thursday, January 30 Upon arrival in Kuala Lumpur, meet your clothing, household items, and more. (B,D) Penang Hill local tour manager and transfer to the Ascend Penang Hill for amazing views of hotel to freshen up for welcome dinner in Tuesday, January 28 the Strait of Malacca from the Sky Deck. a local restaurant. (D) Kuala Lumpur Performance Return to George Town for lunch on own, Morning visit to a local school for a musical followed by a George Town Street Art Tour Monday, January 27 exchange where the ensembles will and entrance to the Pinang Peranakan Kuala Lumpur & Batu Caves perform for each other, or, present a public Museum, a furnished mansion recreating Kuala Lumpur is Malaysia’s capital, as well performance during the Chinese New Year the style of the Straits Chinese heritage. as its financial and cultural center. A celebrations. The remainder of the day is Dinner in a local restaurant. -

Technopolitics of Historic Preservation in Southeast Asian Chinatowns: Penang, Bangkok, Ho Chi Minh City

Technopolitics of Historic Preservation in Southeast Asian Chinatowns: Penang, Bangkok, Ho Chi Minh City By Napong Rugkhapan A dissertation suBmitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Urban and Regional Planning) In the University of Michigan 2017 Doctoral Committee: Professor Martin J. Murray, Chair Associate Professor Scott D. CampBell Professor Linda L. Groat Associate Professor Allen D. Hicken ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without various individuals I have met along the journey. First and foremost, I would like to thank my excellent dissertation committee. The dissertation chair, Professor Martin J. Murray, has been nothing but supportive from day one. I thank Martin for his enthusiasm for comparative urBanism - the same enthusiasm that encouraged me to embark on one. In particular, I thank him for letting me experiment with my own thought, for letting me pursue the direction of my scholarly interest, and for Being patient with my attempt at comparative research. I thank Professor Linda Groat for always Being accessible, patient, and attentive to detail. Linda taught me the importance of systematic investigation, good organization, and clear writing. I thank Professor Scott D. Campbell for, since my first year in the program, all the inspiring intellectual conversations, for ‘ruBBing ideas against one another’, for refreshingly different angles into things I did not foresee. Scott reminds me of the need to always think Broadly aBout cities and theory. I thank Professor Allen D. Hicken for his constant support, insights on comparative research, vast knowledge on Thai politics. Elsewhere on campus, I thank Professor Emeritus Rudolf Mrazek, the first person to comment on my first academic writing. -

PENANG MUSEUMS, CULTURE and HISTORY Abu Talib Ahmad

Kajian Malaysia, Vol. 33, Supp. 2, 2015, 153–174 PENANG MUSEUMS, CULTURE AND HISTORY Abu Talib Ahmad School of Humanities, Universiti Sains Malaysia, MALAYSIA Email: [email protected] The essay studies museums in Penang, their culture displays and cultural contestation in a variety of museums. Penang is selected as case study due to the fine balance in population numbers between the Malays and the Chinese which is reflected in their cultural foregrounding in the Penang State Museum. This ethnic balance is also reflected by the multiethnic composition of the state museum board. Yet behind this façade one could detect the existence of culture contests. Such contests are also found within the different ethnic groups like the Peranakan and non-Peranakan Chinese or the Malays and the Indian-Muslims. This essay also examines visitor numbers and the attractiveness of the Penang Story. The essay is based on the scrutiny of museum exhibits, museum annual reports and conversations with former and present members of the State Museum Board. Keywords: Penang museums, State Museum Board, Penang Story, museum visitors, culture and history competition INTRODUCTION The phrase culture wars might have started in mid-19th century Germany but it came into wider usage since the 1960s in reference to the ideological polarisations among Americans into the liberal and conservative camps (Hunter, 1991; Luke, 2002). Although not as severe, such wars in Malaysia are manifested by the intense culture competition within and among museums due to the pervasive influence of ethnicity in various facets of the national life. As a result, museum foregrounding of culture and history have become contested (Matheson- Hooker, 2003: 1–11; Teo, 2010: 73–113; Abu Talib, 2008: 45–70; 2012; 2015). -

FREEHOLD Theurbanite Effect BEGINS HERE Experiences Work Smart That Pop

FREEHOLD THEUrbanite Effect BEGINS HERE EXPERIENCES WORK SMART THAT POP CONVENIENCE IS HERE SHOOT AND SCORE FOR CREATIVE S TAY ENERGY SMART GO FURTHER Introducing Trion@KL, an exciting mixed development with an urbanite attitude that radiates life, energy, and endless possibilities. Trion@KL is convenience you can own as a freehold serviced apartment. OVERVIEW PROJECT NAME LAND TENURE Trion@KL Freehold DEVELOPER LAND ACRE Binastra Land Sdn Bhd 4.075 acres LOCATION COMPONENTS Kuala Lumpur 2 Blocks 66-Storey Serviced Apartment 1 Block 37-Storey Serviced Apartment Mercure Kuala Lumpur ADDRESS Commercial Component Jalan Sungai Besi, off Jalan Chan Sow Lin, Kuala Lumpur BOLT (TOWER A) – 66-Storey NEO (TOWER B) – 66-Storey SHEEN (TOWER C) – 56-Storey OVERVIEW TOTAL UNITS (RESIDENTIAL) 1344 | BOLT (TOWER A) - 536 , NEO (TOWER B) - 592, SHEEN (TOWER C) - 216 Unit Per Floor (Residental) BOLT (Tower A) - 10 units/floor | NEO (Tower B) - 11 units/floor | SHEEN (Tower C) - 8 units/floor No. of Lift BOLT (Tower A) - 6 + 1 | NEO (Tower B) - 6 + 1 | SHEEN (Tower C) - 4 + 1 Total No. of Retail Lots 38 Total of Retail lot GFA 86,047 SQ. FT. Total No. of Hotel Rooms 235 Rooms Schedule of Payment Under Schedule H (Applicable to residential unit only) Expected 1st SPA Signing Yet To Confirm Expected Completion Date Q4 of 2023 Maintenance Fee Estimated RM 0.36 psf , Total Carparks Residential - 1,881 | Hotel - 158 | Retail - 244 | Total - 2,283 Selling Price BOLT (Tower A) - RM549,800 - RM946,800 NEO (Tower B) - RM549,800 - RM914,800 SHEEN (Tower C) - RM594,800 - RM831,800 A WORLD OF EASE SEAMLESS CONNECTIVITY Live close to five major roads and highways: Jalan Tun Razak, Jalan Istana, Jalan Sungai Besi, the Besraya Highway, INTEGRATED and the Maju Expressway (MEX). -

Steeped in History, Surrounded by Unesco Heritage Attractions

Call AGB @ Georgetown Chambers The Rice Miller Hotel & Godowns No.2, China Street Ghaut, 10300 Penang, Malaysia Penang UNESCO World Heritage Site T +6 04 262 3818 / 264 3818 F +6 04 262 6818 www.thericemiller.com Sleep easy HistorY RESTYLED as SHEER LUXURY 27 Studio Suites 18 Harbourview Suites As an enduring tribute to its original founder’s Rice Miller Penthouse 21 Service Residences entrepreneurial spirit and remarkable adventures, The Rice Miller Hotel & Godowns is ready to dazzle Play and shine on the exact site where the 19th century Hammam Spa, Fitness Floor, Infinity pool, rice miller first found fame and fortune. The island’s Exclusive Membership Club Steeped In History, Surrounded By new pride is ushering in a modern era of fame and Unesco Heritage Attractions: Savour glamour on Weld Quay’s waterfront. 6 dining venues: Kate at 9, The Green House, The Mill, ZyP, Sweet Spot and Lobby Lounge The Rice Miller is steps away from the spot where, in 1786, A resplendent example of neo-classical architecture, Sir Francis Light raised the British flag for its first foothold in the hotel radiates contemporary cool and lavishes Malaya. Beach Street, or Bankers’ Street as it is also locally Meet known, was Penang’s earliest thoroughfare and continues to Cultural & corporate venues, guests with ultra-plush comforts and amenities. be an important business precinct today. Capacity - up to 300 guests Here at The Rice Miller, in the heart of a UNESCO The beloved 19th century clock tower and historical landmark Shop holds many memories and is forgiven for its idiosyncratic Boutiques and World Heritage site, vintage Georgetown meets time keeping.