Police Gurdwaras of the Straits Settlements and the Malay States (1874-1957)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Government Transformation Programme the Roadmap Diterbitkan Pada 28 Januari 2010

Government Transformation Programme The Roadmap Diterbitkan pada 28 Januari 2010 ©Hak cipta Unit Pengurusan Prestasi dan Pelaksanaan (PEMANDU), Jabatan Perdana Menteri Hak cipta terpelihara, tiada mana-mana bahagian daripada buku ini boleh diterbitkan semula, disimpan untuk pengeluaran atau ditukar kepada apa-apa bentuk dengan sebarang cara sekalipun tanpa izin daripada penerbit. Diterbit oleh: Unit Pengurusan Prestasi Dan Pelaksanaan (PEMANDU) Jabatan Perdana Menteri Aras 3, Blok Barat, Pusat Pentadbiran Kerajaan Persekutuan 62502 Putrajaya Tel: 03-8881 0128 Fax: 03-8881 0118 Email: [email protected] Laman Web: www.transformation.gov.my Dicetak oleh: Percetakan Nasional Malaysia Berhad (PNMB) Jalan Chan Sow Lin 50554 Kuala Lumpur Tel: 03-9236 6895 Fax: 03-9222 4773 Email: [email protected] Laman Web: www.printnasional.com.my Government Transformation Programme The Roadmap Foreword It is clear that Malaysia has achieved much as a young nation. We have made significant strides in eradicating hardcore poverty, we have developed a diversified economic base, increased the quality of life of the average citizen and created a progressive civil service which embraces change. But it is also clear that we face significant challenges to achieve the ambitious goals of Vision 2020, by the year 2020. I am confident that this Government Transformation Programme (GTP) Roadmap is what we need to help chart our path towards Vision 2020. It details a bold and unprecedented programme to begin to transform the Government and to renew the Government’s focus on delivering services to the rakyat. The scope of this GTP is broad, and will encompass every Ministry within government. -

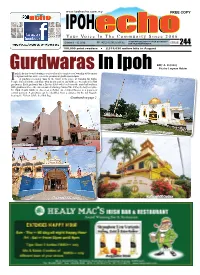

Your Voice in the Community Since 2006

www.ipohecho.com.my FREE COPY IPOH Your Voiceechoecho In The Community Since 2006 October 1 - 15, 2016 PP 14252/10/2012(031136) 30 SEN FOR DELIVERY TO YOUR DOORSTEP – ISSUE ASK YOUR NEWSVENDOR 244 100,000 print readers 2,315,636 online hits in August By A. Jeyaraj Pics by Luqman Hakim Gurdwaraspoh Echo has been featuring a series of articles on places of worship of the major In Ipoh religions and this issue covers the prominent gurdwaras in Ipoh. I A gurdwara meaning 'door to the Guru' is the place of worship for Sikhs. People from all faiths, and those who do not profess any faith, are welcomed in Sikh gurdwaras. Each gurdwara has a Darbar Sahib which refers to the main hall within a Sikh gurdwara where the current and everlasting Guru of the Sikhs, the holy scripture Sri Guru Granth Sahib, is placed on a Takhat (an elevated throne) in a prominent central position. A gurdwara can be identified from a distance by the tall flagpole bearing the Nishan Sahib, the Sikh flag. Continued on page 2 Gurdwara Sahib Greentown Central Sikh Temple Gurdwara Sahib Bercham Gurdwara Sahib Buntong 2 October 1 - 15, 2016 IPOH ECHO Your Voice In The Community Gurdwaras: a focal point for all Sikh religious, cultural and community activities erak, where most of the early Sikhs settled, and wherever there were Sikhs, a gurdwara was sure to follow, has the most number of gurdwaras with 42 out of a Gurdwara Sahib Greentown, Jalan Hospital Ptotal of 119 in Malaysia. The Gurdwara Sahib Greentown is situated on a hilltop and commands a majestic view of the surroundings. -

Annual Report of the Sikh Advisory Board for the Period November 2018 to October 2019

<> siqgur pRswid SIKH ADVISORY BOARD (Statutory Board Established Under Ministry of Community Development) 2, Towner Road #03-01, Singapore 327804 Telephone: (65)9436 4676 (Malminderjit Singh, Secretary, SAB) Email: [email protected] Annual Report of the Sikh Advisory Board for the period November 2018 to October 2019 1. Meetings of the Sikh Advisory Board (SAB or Board) The Board, which has been appointed to serve a three-year term from November 2017 to October 2020, met for its second year of quarterly meetings as scheduled in 2019 on 13 February, 22 May, 14 August and 6 November. 2. Major Items discussed or addressed by the Board 2.1. Proposed Amendments to the SAB Rules Proposed amendments regarding a more equitable representation of the structure of the community and sustainability and diversity of the Board were submitted to the Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth (MCCY) for consideration and final approval. The proposed amendments to increase the representation for the Central Sikh Gurdwara Board (CSGB) and the Gurdwara Sahib Yishun – from one to two members each - to ensure parity with other Gurdwaras, will remain. The MCCY asked the SAB to reword sections of the amendments with specific reference to diversity and gender. The MCCY advised the SAB to consider such amendments to be a part of any best practices guidelines rather than to be incorporated into the rules and regulations of the SAB as that will give the SAB more flexibility to review its diversity needs as and when needed. The revised document is now pending the Minister’s approval. If approved, the SAB will have 17 members on the Board when the new term begins in November 2020 instead of the current 15. -

Singapore 2019 International Religious Freedom Report

SINGAPORE 2019 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The constitution, laws, and policies provide for religious freedom, subject to restrictions relating to public order, public health, and morality. The government continued to ban Jehovah’s Witnesses and the Family Federation for World Peace and Unification (Unification Church). The government restricted speech or actions it perceived as detrimental to “religious harmony.” In October parliament passed legislation (not yet in effect at year’s end) that will allow the minister of home affairs to take immediate action against individuals deemed to have insulted a religion or to have incited violence or feelings of enmity against a religious group. The same bill will limit foreign funding to, leadership of, and influence over, local religious organizations. There is no legal provision for conscientious objection to military service, including on religious grounds. Jehovah’s Witnesses reported 11 conscientious objectors remained detained at year’s end. The government continued to ban all religious processions on foot, except for those of three Hindu festivals, including Thaipusam, and it reduced restrictions on the use of live music during Thaipusam. Authorities cancelled a concert by Swedish band Watain after public complaints that the group was offensive towards Christians and Jews. Authorities banned a foreign clergyman from preaching in Singapore after he refused to return to the country for a police investigation into anti-Muslim comments he had reportedly made at a Christian evangelical conference in 2018. The government made multiple high-level affirmations of the importance of religious harmony and respect for religious differences, including in June during a 1,000-person international conference it had organized to discuss religious diversity and cohesion in diverse societies. -

FREEHOLD Theurbanite Effect BEGINS HERE Experiences Work Smart That Pop

FREEHOLD THEUrbanite Effect BEGINS HERE EXPERIENCES WORK SMART THAT POP CONVENIENCE IS HERE SHOOT AND SCORE FOR CREATIVE S TAY ENERGY SMART GO FURTHER Introducing Trion@KL, an exciting mixed development with an urbanite attitude that radiates life, energy, and endless possibilities. Trion@KL is convenience you can own as a freehold serviced apartment. OVERVIEW PROJECT NAME LAND TENURE Trion@KL Freehold DEVELOPER LAND ACRE Binastra Land Sdn Bhd 4.075 acres LOCATION COMPONENTS Kuala Lumpur 2 Blocks 66-Storey Serviced Apartment 1 Block 37-Storey Serviced Apartment Mercure Kuala Lumpur ADDRESS Commercial Component Jalan Sungai Besi, off Jalan Chan Sow Lin, Kuala Lumpur BOLT (TOWER A) – 66-Storey NEO (TOWER B) – 66-Storey SHEEN (TOWER C) – 56-Storey OVERVIEW TOTAL UNITS (RESIDENTIAL) 1344 | BOLT (TOWER A) - 536 , NEO (TOWER B) - 592, SHEEN (TOWER C) - 216 Unit Per Floor (Residental) BOLT (Tower A) - 10 units/floor | NEO (Tower B) - 11 units/floor | SHEEN (Tower C) - 8 units/floor No. of Lift BOLT (Tower A) - 6 + 1 | NEO (Tower B) - 6 + 1 | SHEEN (Tower C) - 4 + 1 Total No. of Retail Lots 38 Total of Retail lot GFA 86,047 SQ. FT. Total No. of Hotel Rooms 235 Rooms Schedule of Payment Under Schedule H (Applicable to residential unit only) Expected 1st SPA Signing Yet To Confirm Expected Completion Date Q4 of 2023 Maintenance Fee Estimated RM 0.36 psf , Total Carparks Residential - 1,881 | Hotel - 158 | Retail - 244 | Total - 2,283 Selling Price BOLT (Tower A) - RM549,800 - RM946,800 NEO (Tower B) - RM549,800 - RM914,800 SHEEN (Tower C) - RM594,800 - RM831,800 A WORLD OF EASE SEAMLESS CONNECTIVITY Live close to five major roads and highways: Jalan Tun Razak, Jalan Istana, Jalan Sungai Besi, the Besraya Highway, INTEGRATED and the Maju Expressway (MEX). -

Notes and References

Notes and References 1 The Growth of Trade, Trading Networks and Mercantilism in Pre-colonial South-East Asia I. Victor B. Lieberman, 'Local integration and Eurasian analogies: structuring South East Asian history c.1350-c.l830', Modem Asian Studies, 27, 3 (1993) p. 477. 2. Ibid., p. 480. 3. Victor B. Lieberman, Burmese Administrative Cycles: Anarchy and Conquest, c./580-1760 (Princeton, 1984) p. 21. 4. James C. Ingram, Economic Change in Thailand 1850-1970 (Stanford, 1971) p. 12. 5. Sompop Manarungsan, The Economic Development of Thailand 1850-1950: Re sponse to the Challenge of the World Economy (Bangkok, 1989) p. 32. 6. Lieberman (1993) p. 500. 7. Anthony Reid, 'Economic and social change c.l400-1800', in Nicholas Tarling (ed.) The Cambridge History of South-East Asia, from Early Times to c./800, vol. I (Cambridge, 1992) pp. 481-3. For a stimulating study of how Dutch intervention and the native Islamic reform movements eroded indigenous capital ist development in coffee production, see C. Dobbin, Islamic Revivalism in a Changing Peasant Economy: Central Srw~atra 1784-1847 (London, 1983). 8. Anthony Reid, 'The origins of revenue farming in South-East Asia', in John Butcher and Howard Dick (eds) The Rise and Fall of Revenue Farming: Busi ness Elites and the Emergence of the Modern State in South-East Asia (London, 1993) pp. 70-1. 9. Anthony Reid, 'The seventeenth century crisis in South-East Asia', Modern Asian Studies 24 (October 1990) pp. 642-5; Denys Lombard and Jean Aubin (eds) Marc/rands et hommes d'affaires asiatiques dans /'Ocean lndien et Ia Mer de Chine, 13e-20e sitkles (Paris, 1988). -

Sri Guru Singh Sabha Southall

SRI GURU SINGH SABHA SOUTHALL Financial Statements For the Period Ended 31 December 2017 CHARITY NUMBER: 280707 SRI GURU SINGH SABHA SOUTHALL Financial Statements PERIOD ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2017 CONTENTS PAGE Charity Reference and Administrative Details Trustees' Annual Report 2 to 9 Independent Auditor's report to the trustees 10 to 12 Statement of Financial Activities 13 Statement of Financial Position 14 Cash Flow Statement 16 Notes to the Accounts 16 to 23 SRI GURU SINGH SABHA SOUTHALL CHARITY REFERENCE AND ADMINISTRATIVE DETAILS PERIOD ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2017 The trustees present their report and the Financial Statements of Sri Guru Singh Sabha Southail for the period ended 31 December 2017. REFERENCE AND ADMINISTRATIVE DETAILS Registered Chadity Name Sri Guru Singh Sabha Southall Charity Registration Number 280707 Principal Office 2-8 Park Avenue Southall Middlesex UB13AG Registered Office 2-8 Park Avenue Southall Middlesex U81 3AG The Trustees The trutees who served the charity dunng the period were as follows: Mr Balwant Singh Gill, Holding Trustee Mr Surjit Singh Bilga, Holding Trustee- Deceased on 24/06/2018 Mr Perte& Bakhtawar Singh Johal, Holding Trustee Mr Amarjit Singh Dassan, Holding Trustee Auditor RSA Associates Accountants & Registered Auditors First Floor 30 Merrick Road Southall Middlesex England U82 4AU Page 1 SRI GURU SINGH SABHA SOUTHALL TRUSTEES' ANNUAL REPORT PERIOD ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2017 Trustees Report The Managing Trustees present their report with the financial statements of the Charity for the period ended 31 December 2017. The trustees have adopted the provisions of the statement of recommended Practice (SORP) 'Accounting and reporting by charities' (FRS 102) inpreparing the annual report and financial statements of the Charity. -

LI-DISSERTATION-2015.Pdf

Copyright by Wai Chung LI 2015 The Dissertation Committee for Wai Chung LI Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Sikh Gurmat Sangīt Revival in Post-Partition India Committee: Stephen Slawek, Supervisor Andrew Dell’Antonio Gordon Mathews Kamran Ali Robin Moore Veit Erlmann The Sikh Gurmat Sangīt Revival in Post-Partition India by Wai Chung LI, MPhil. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2015 Acknowledgements I would like to thank the following individual and parties for making this project possible. First of all, I would like to express my sincere gratitude and respect to Professor Stephen Slawek, who always enlightens me with intellectual thoughts and personal advice. I would also like to thank other members of my doctoral committee, including Professor Andrew Professor Dell’Antonio, Professor Gordon Mathews, Professor Kamran Ali, Professor Robin Moore, and Professor Veit Erlmann for their insightful comments and support towards this project. I am grateful to the staff of the following Sikh temples and academic institutions where research was conducted: The Archives and Research Center for Ethnomusicology; The American Institute of Indian Studies, Haryana; Gurdwara Sahib Austin, Texas; Jawaddi Taksal, Ludhiana; Gurdwara Sahib Silat Road, Singapore; Khalsa Diwan (Hong Kong) Sikh Temple, Hong Kong; Punjabi University Patiala, Patiala; The Harmandir Sahib, Amritsar; and The Sikh Center, Central Sikh Gurdwara Board, Singapore. I owe a debt of gratitute to people affiliated with the Jawaddi Taksal, Ludhiana, as they made my time in India (especially Punjab) enjoyable and memorable. -

43\Nov 02-1\91\11\21 Address by Prime Minister Mr Goh Chok

1 Release No.: 43\NOV 02-1\91\11\21 ADDRESS BY PRIME MINISTER MR GOH CHOK TONG, AT THE CENTRAL SIKH TEMPLE, AT TOWNER ROAD, ON THURSDAY, 21 NOVEMBER 1991 AT 9.30 AM I am very happy to join you today on the occasion of the 523rd anniversary of Guru Nanak’s birth. Among the many wise teachings of your religious founder, I want to mention just one of his precepts which Sikhs practice constantly and are justifiably known for - that of sharing and caring or Wand Chanka. The symbolic gestures we all made when we entered the Gurdwara testify to the way of life of Sikhs - of living on one’s efforts, of caring, of giving. I would like to expand on this theme today and share with you some thoughts on the Government’s philosophy towards community self help. gct\1991\gct1121.doc 2 All communities share the common aspiration of attaining a higher standard of living. We crystallized this in 1984 by targeting to reach the Swiss standard of living then by 1999. In other words, we felt we could level up to the Swiss per capita income in 15 years. Today, our capita income is S$20,000 (1984 prices). Our economy is expected to grow by about six per cent per year over the next few years. At this rate we can achieve our income target of S$30,000 (1984 prices) per capita by 1999. This income is the average for the country. Some will earn more than this, while others less. -

Giro Donation Form

CENTRAL SIKH GURDWARA BOARD – GIRO DONATION FORM My Personal Particulars Dear Sir, I would like to make the following contributions: Name: _____________________________________ 1. A monthly contribution of: Address: _____________________________________ □ $251 □ $101 □ $51 _____________________________________________ □ $21 Other amounts □ $_____ NRIC No.: _______________ Date of Birth: __________ 2. A one-time contribution of: Email: ___________________________________ □ $11,000 □ $5,000 □ $3,000 □ $2,000 Other amounts □ $_____ Telephone: _____________ (Home) _____________ (Hd) Occupation (Optional): __________________________ I have completed the Application Form below. PART 1: APPLICATION FORM FOR INTERBANK GIRO - PART 1: FOR DONOR’S COMPLETION Date: ________________________________________ Name of Billing Organisation: ____________________________________________ CENTRAL SIKH GURDWARA BOARD____ Name of Bank ____________________________________ ________________________________________ Reference Number Branch a) I/We hereby instruct you to process the Central Sikh Gurdwara Board’s instructions to debit my/our account. b) You are entitled to reject the Central Sikh Gurdwara Board’s instructions if my/our account does not have sufficient funds and charge me/us a fee for this. You may also at your discretion allow the debit even if this results in overdraft on the account and impose charges accordingly. c) This authorization will remain in force until terminated by your written notice sent to my/our address last known to you or upon receipt -

Gurdwara Sri Guru Singh Sabha, Southall

Sri Guru Singh Sabha (Southall) A History: 1958 - 2019 1950s Shepherds Bush Gurdwara In the 1950s the only Gurdwara in London was established in Putney in 1911 by the Khalsa Jatha: British Isles (London). In 1913 it was moved to 79 Sinclair Road, London W14 (Shepherds Bush), following a donation from Maharaja Bhupinder Singh of Patiala. The “Shepherds Bush” Gurdwara, also known as Bhupinder Dharmsala, held weekly Diwans in the early 1950s and in 1954 appointed a full-time Granthi. Supported by This Gurdwara acted as a temporary refuge, transit point and a community-cum-social point and was an integral part of the “journey” of most early Sikhs, arriving in Britain in the 1950s. Shaheed Udham Singh stayed at this Gurdwara. Produced by Balraj Singh Purewal: April 2019 Shackleton Hall Sohal Singh Rai (Akali) Dharam Singh Sandhu Jaswant Singh Dhami Ram Singh Flora Surjit Singh Bilga 1958 The Society’s founding members included: Sikh Cultural Society: Sohan Singh Rai (Akali) Shackleton Hall Jaswant Singh Dhami Ram Singh Flora Sikhs from Southall using the Shepherds Bush Karam Singh Khela Gurdwara established the Sikh Cultural Society, Surjit Singh Bilga the first Sikh organisation in Southall, to work Dharam Singh Sandhu towards setting up a Gurdwara in Southall and Attar Singh to provide a platform and voice for the Sikh Chacha Darshan Singh community. Gurbaksh Singh In 1958, the Society started hiring Shackleton Phuman Singh Sohal Hall on Shackleton Road and hosting prayers In the preceding years, Shackleton Hall became once a month on Sundays, with Sewadars an established place of worship and also as preparing basic food at home and serving it as a venue for Sikh weddings and other religious Guru Ka Langar at the Hall. -

Sikhism-A Very Short Introduction

Sikhism: A Very Short Introduction Very Short Introductions are for anyone wanting a stimulating and accessible way in to a new subject. They are written by experts, and have been published in more than 25 languages worldwide. The series began in 1995, and now represents a wide variety of topics in history, philosophy, religion, science, and the humanities. Over the next few years it will grow to a library of around 200 volumes – a Very Short Introduction to everything from ancient Egypt and Indian philosophy to conceptual art and cosmology. Very Short Introductions available now: ANARCHISM Colin Ward CHRISTIANITY Linda Woodhead ANCIENT EGYPT Ian Shaw CLASSICS Mary Beard and ANCIENT PHILOSOPHY John Henderson Julia Annas CLAUSEWITZ Michael Howard ANCIENT WARFARE THE COLD WAR Robert McMahon Harry Sidebottom CONSCIOUSNESS Susan Blackmore THE ANGLO-SAXON AGE Continental Philosophy John Blair Simon Critchley ANIMAL RIGHTS David DeGrazia COSMOLOGY Peter Coles ARCHAEOLOGY Paul Bahn CRYPTOGRAPHY ARCHITECTURE Fred Piper and Sean Murphy Andrew Ballantyne DADA AND SURREALISM ARISTOTLE Jonathan Barnes David Hopkins ART HISTORY Dana Arnold Darwin Jonathan Howard ART THEORY Cynthia Freeland Democracy Bernard Crick THE HISTORY OF DESCARTES Tom Sorell ASTRONOMY Michael Hoskin DINOSAURS David Norman Atheism Julian Baggini DREAMING J. Allan Hobson Augustine Henry Chadwick DRUGS Leslie Iversen BARTHES Jonathan Culler THE EARTH Martin Redfern THE BIBLE John Riches EGYPTIAN MYTH BRITISH POLITICS Geraldine Pinch Anthony Wright EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY Buddha Michael Carrithers BRITAIN Paul Langford BUDDHISM Damien Keown THE ELEMENTS Philip Ball BUDDHIST ETHICS Damien Keown EMOTION Dylan Evans CAPITALISM James Fulcher EMPIRE Stephen Howe THE CELTS Barry Cunliffe ENGELS Terrell Carver CHOICE THEORY Ethics Simon Blackburn Michael Allingham The European Union CHRISTIAN ART Beth Williamson John Pinder EVOLUTION MATHEMATICS Timothy Gowers Brian and Deborah Charlesworth MEDICAL ETHICS Tony Hope FASCISM Kevin Passmore MEDIEVAL BRITAIN FOUCAULT Gary Gutting John Gillingham and Ralph A.