Women and the World's Columbian Exposition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mounted on a Pedestal: Bertha Honoré Palmer Hope L

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 11-8-2007 Mounted on a Pedestal: Bertha Honoré Palmer Hope L. Black University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Black, Hope L., "Mounted on a Pedestal: Bertha Honoré Palmer" (2007). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/637 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mounted on a Pedestal: Bertha Honoré Palmer by Hope L. Black A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Liberal Arts Department of Humanities College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida CoMajor Professor: Gary Mormino, Ph.D. CoMajor Professor: Raymond Arsenault, Ph.D. Julie Armstrong, Ph.D. Date of Approval: November 8, 2007 Keywords: World’s Columbian Exposition, Meadowsweet Pastures, Great Chicago Fire, Manatee County, Seaboard Air Line Railroad © Copyright 2007, Hope L. Black Acknowledgements With my heartfelt appreciation to Professors Gary Mormino and Raymond Arsenault who allowed me to embark on this journey and encouraged and supported me on every path; to Greta ScheidWells who has been my lifeline; to Professors Julie Armstrong, Christopher Meindl, and Daryl Paulson, who enlightened and inspired me; to Ann Shank, Mark Smith, Dan Hughes, Lorrie Muldowney and David Baber of the Sarasota County History Center who always took the time to help me; to the late Rollins E. -

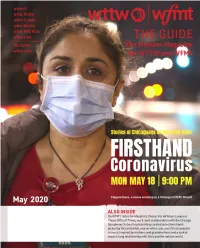

Wwciguide May 2020.Pdf

From the President & CEO The Guide The Member Magazine Dear Member, for WTTW and WFMT Thank you for your viewership, listenership, and continued support of WTTW and Renée Crown Public Media Center 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue WFMT. Now more than ever, we believe it is vital that you can turn to us for trusted Chicago, Illinois 60625 news and information, and high quality educational and entertaining programming whenever and wherever you want it. We have developed our May schedule with this Main Switchboard in mind. (773) 583-5000 Member and Viewer Services On WTTW, explore the personal, firsthand perspectives of people whose lives (773) 509-1111 x 6 have been upended by COVID-19 in Chicago in FIRSTHAND: Coronavirus. This new series of stories produced and released on wttw.com and our social media channels Websites wttw.com has been packaged into a one-hour special for television that will premiere on wfmt.com May 18 at 9:00 pm. Also, settle in for the new two-night special Asian Americans to commemorate Asian Pacific American Heritage Month. As America becomes more Publisher diverse, and more divided while facing unimaginable challenges, this film focuses a Anne Gleason Art Director new lens on U.S. history and the ongoing role that Asian Americans have played. On Tom Peth wttw.com, discover and learn about Chicago’s Japanese Culture Center established WTTW Contributors Julia Maish in 1977 in Chicago by Aikido Shihan (Teacher of Teachers) and Zen Master Fumio Lisa Tipton Toyoda to make the crafts, philosophical riches, and martial arts of Japan available WFMT Contributors to Chicagoans. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

SILVER SPRINGS: THE FLORIDA INTERIOR IN THE AMERICAN IMAGINATION By THOMAS R. BERSON A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Thomas R. Berson 2 To Mom and Dad Now you can finally tell everyone that your son is a doctor. 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my entire committee for their thoughtful comments, critiques, and overall consideration. The chair, Dr. Jack E. Davis, has earned my unending gratitude both for his patience and for putting me—and keeping me—on track toward a final product of which I can be proud. Many members of the faculty of the Department of History were very supportive throughout my time at the University of Florida. Also, this would have been a far less rewarding experience were it not for many of my colleagues and classmates in the graduate program. I also am indebted to the outstanding administrative staff of the Department of History for their tireless efforts in keeping me enrolled and on track. I thank all involved for the opportunity and for the ongoing support. The Ray and Mitchum families, the Cheatoms, Jim Buckner, David Cook, and Tim Hollis all graciously gave of their time and hospitality to help me with this work, as did the DeBary family at the Marion County Museum of History and Scott Mitchell at the Silver River Museum and Environmental Center. David Breslauer has my gratitude for providing a copy of his book. -

French Impressionist and Post Impressionist Paintings from the Collections of Mrs. Bertha Palmer Thorne and Mr. Gordon Palmer

FRENCH IMPRESSIONIST AND POST IMPRESSIONIST PAINTINGS from the Collections of MRS. BERTHA PALMER THORHE AND MR. GORDOH PALMER CATALOGUE WALKER ART MUSEUM Bowdoin College Bninf^wick, Maine May 11 ' June 17, 1962 Mrs. Bertha Palmer Thorne and Gordon Palmer are grandchildren of Mrs. Potter Palmer of Chicago who, in 1889, was one of the first Americans to introduce French Impressionst Painting to this country. While the greatest portion of Mrs. Palmer's collection is in the Art Institute of Chicago, many of the pictures in this exhibition were among those acquired by her. To this original group, our lenders have since added several important examples ranging in time and taste from Bou' din's La Plage to Picasso's Two Pigeons. It is a privilege for the Walker Art Museum of Bowdoin College to be able to present to a new audience such a distinguished group of pictures, many of which were the first of their kind to reach our shores. M. S. S. Lent by Mrs. Bertha Palmer Thorne Jean'Antoine Houdon (1714-1828), Portrait of a Little Girl, bronze sculpture Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot (1796' 1875), Trois Jeunes Filles pres d'un Arbre, oil Eugene Boudin (1824-1898), La Plage, oil Edouard Manet (1832-1883), Portrait of Berthe Morisot, lithograph Hilaire Germaine Edgar Degas (1834-1917), Mile. Wol\ons\a, etching Degas, Interior with Dancers^ monotype Henri Fantin-Latour (1836-1904), Women Embroidering^ lithograph Alfred Sisley (1839-1899), Landscape, oil Paul Cezanne (1839-1906), The Indwell, watercolor Cezanne, The ^uarrv, watercolor Cezanne, Mont St. -

The Woman's Building of the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893

The Invisible Triumph: The Woman's Building of the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893 JAMES V. STRUEBER Ohio State University, AT1 JOHANNA HAYS Auburn University INTRODUCTION from Engineering Magazine, The World's Columbian Exposition (WCE) was the first world exposition outside of Europe and was to Thus has Chicago gloriously redeemed the commemorate the four hundredth anniversary of obligations incurred when she assumed the Columbus reaching the New World. The exhibition's task of building a World's Fair. Chicago's planners aimed at exceeding the fame of the 1889 businessmen started out to prepare for a Paris World Exposition in physical size, scope of finer, bigger, and more successful enter- accomplishment, attendance, and profitability.' prise than the world had ever seen in this With 27 million attending equaling approximately line. The verdict of the jury of the nations 40% of the 1893 US population, they exceeded of the earth, who have seen it, is that it the Paris Exposition in all accounts. This was partly is unquestionably bigger and undoubtedly accomplished by being open on Sundays-a much finer, and now it is assuredly more success- debated moral issue-the attraction of the newly ful. Great is Chicago, and we are prouder invented Ferris wheel, cheap quick nationwide than ever of her."5 transportation provided by the new transcontinental railroad system all helped to make a very successful BACKGROUND financial plans2Surprisingly, the women's contribu- tion to the exposition, which included the Woman's Labeled the "White City" almost immediately, for Building and other women's exhibits accounted for the arrangement of the all-white neo-Classical and 57% of total exhibits at the exp~sition.~In addition neo-High Renaissance architectural style buildings railroad development to accommodate the exposi- around a grand court and fountain poolI6 the WCE tion, set the heart of American trail transportation holds an ironic position in American history. -

Historic Properties Identification Report

Section 106 Historic Properties Identification Report North Lake Shore Drive Phase I Study E. Grand Avenue to W. Hollywood Avenue Job No. P-88-004-07 MFT Section No. 07-B6151-00-PV Cook County, Illinois Prepared For: Illinois Department of Transportation Chicago Department of Transportation Prepared By: Quigg Engineering, Inc. Julia S. Bachrach Jean A. Follett Lisa Napoles Elizabeth A. Patterson Adam G. Rubin Christine Whims Matthew M. Wicklund Civiltech Engineering, Inc. Jennifer Hyman March 2021 North Lake Shore Drive Phase I Study Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... v 1.0 Introduction and Description of Undertaking .............................................................................. 1 1.1 Project Overview ........................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 NLSD Area of Potential Effects (NLSD APE) ................................................................................... 1 2.0 Historic Resource Survey Methodologies ..................................................................................... 3 2.1 Lincoln Park and the National Register of Historic Places ............................................................ 3 2.2 Historic Properties in APE Contiguous to Lincoln Park/NLSD ....................................................... 4 3.0 Historic Context Statements ........................................................................................................ -

Cultural Resource Assessment Survey Lakewood Ranch Boulevard Extension Sarasota County, Florida

CULTURAL RESOURCE ASSESSMENT SURVEY LAKEWOOD RANCH BOULEVARD EXTENSION SARASOTA COUNTY, FLORIDA Performed for: Kimley-Horn 1777 Main Street, Suite 200 Sarasota, Florida 34326 Prepared by: Florida’s First Choice in Cultural Resource Management Archaeological Consultants, Inc. 8110 Blaikie Court, Suite A Sarasota, Florida 34240 (941) 379-6206 Toll Free: 1-800-735-9906 June 2016 CULTURAL RESOURCE ASSESSMENT SURVEY LAKEWOOD RANCH BOULEVARD EXTENSION SARASOTA COUNTY, FLORIDA Performed for: Kimley-Horn 1777 Main Street, Suite 200 Sarasota, Florida 34326 By: Archaeological Consultants, Inc. 8110 Blaikie Court, Suite A Sarasota, Florida 34240 Marion M. Almy - Project Manager Lee Hutchinson - Project Archaeologist Katie Baar - Archaeologist Thomas Wilson - Architectural Historian June 2016 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A cultural resource assessment survey (CRAS) of the Lakewood Ranch Boulevard Extension, in Sarasota, Florida, was performed by Archaeological Consultants, Inc (ACI). The purpose of this survey was to locate and identify any cultural resources within the project area and to assess their significance in terms of eligibility for listing in the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) and the Sarasota County Register of Historic Places (SCRHP). This report is in compliance with the Historic Preservation Chapter of Apoxsee and Article III, Chapter 66 (Sub-Section 66-73) of the Sarasota County Code, as well as with Chapters 267 and 373, Florida Statutes (FS), Florida’s Coastal Management Program, and implementing state regulations regarding possible impact to significant historical properties. The report also meets specifications set forth in Chapter 1A-46, Florida Administrative Code (FAC) (revised August 21, 2002). Background research, including a review of the Florida Master Site File (FMSF), and the NRHP indicated no prehistoric archaeological sites were recorded in the project area. -

Chicago's West Loop

The CROSSROADS Old St. Patrick’s Bulletin A Catholic Community in Chicago's West Loop SUNDAY, JANUARY 31, 2021 2 | St. Valentine's Mass 3 | Awakenings 4 | Broadway on Adams 5 | Green Team 6 | Pancake Breakfast 7 | Giving 8 | Living into the Vision Pancake Breakfast has been a Foundations tradition for fifteen years. While we cannot be 9 | Happenings together in the Old St. Pat's hall this year, will you help us carry on the tradition?! 10 | First Friday We invite you to make pancakes for your family, your roommate, or your neighbor this Sunday 11 | Evenings with Encore and donate $5 to Foundations Youth Ministry Worktours. 12 | Community Life To donate, visit bit.ly/pancakebreakfast2021 | Hearts & Prayers See page six for more details! 13 14 | Directory old st. patrick’s church oldstpats oldstpatschicago ST. VALENTINE'S DAY MASS directory valentine's mass valentine's Saturday, February 13 | 6 pm | livestream.com/oldstpats/valentinesmass2021 "We believe that where any married people are living together in love, God is present, and good things happen, and lives are full." ~ Jack Shea Please join us for this annual tradition at Old St. Pat's - one which will not be missed because of a global pandemic! The St. Valentine's Day Mass is a chance to carve out time to celebrate liturgy, community, and the mysterious and treacherous love called for and lived out in marriage. All are welcome to celebrate with us via Livestream, and all married couples are welcome to renew their expressions of commitment during the liturgy. Instead of filing our limited number of available seats for this Mass, we will all celebrate this liturgy remotely: at home and in the places where we try to live into this sacramental reality of marriage each day. -

The New Women of Chicago's World's Fairs, 1893-1934 By

New Women, New Opportunities: The New Women of Chicago’s World’s Fairs, 1893-1934 By Taylor Jade Mills A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY-MUSEUM STUDIES University of Central Oklahoma 2018 Table of Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... i List of Illustrations ................................................................................................................... iii Acknowledgments ..................................................................................................................... v Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 1 Chapter 1: Consigned to the Sideshow: Women’s Role in World’s Fair Scholarship ........... 6 World’s Fair Literature ............................................................................................................ 8 The New Woman and Other Concepts ................................................................................... 18 Chapter 2: Old Women with New Opportunities: Chronicling the New Woman in the United States .......................................................................................................................... 25 Woman’s World’s Fair, 1925-1928 ......................................................................................... 31 Chapter -

Auguste Rodin 1 Auguste Rodin

Auguste Rodin 1 Auguste Rodin Auguste Rodin Birth name François-Auguste-René Rodin Born 12 November 1840Paris Died 17 November 1917 (aged 77)Meudon, Île-de-France Nationality French Field Sculpture, drawing Works The Age of Bronze (L'age d'airain), 1877 The Walking Man (L'homme qui marche), 1877-78 The Burghers of Calais (Les Bourgeois de Calais), 1889 The Kiss, 1889 The Thinker (Le Penseur), 1902 Awards Légion d'Honneur François-Auguste-René Rodin (12 November 1840 – 17 November 1917), known as Auguste Rodin (English pronunciation: /oʊˈɡuːst roʊˈdæn/ oh-goost roh-dan, French pronunciation: [ogyst ʁɔdɛ̃]), was a French sculptor. Although Rodin is generally considered the progenitor of modern sculpture,[1] he did not set out to rebel against the past. He was schooled traditionally, took a craftsman-like approach to his work, and desired academic recognition,[2] although he was never accepted into Paris's foremost school of art. Sculpturally, Rodin possessed a unique ability to model a complex, turbulent, deeply pocketed surface in clay. Many of his most notable sculptures were roundly criticized during his lifetime. They clashed with the predominant figure sculpture tradition, in which works were decorative, formulaic, or highly thematic. Rodin's most original work departed from traditional themes of mythology and allegory, modeled the human body with realism, and celebrated individual character and physicality. Rodin was sensitive of the controversy surrounding his work, but refused to change his style. Successive works brought increasing favor from the government and the artistic community. From the unexpected realism of his first major figure—inspired by his 1875 trip to Italy—to the unconventional memorials whose commissions he later sought, Rodin's reputation grew, such that he became the preeminent French sculptor of his time. -

Inventing the Lady Manager: Rhetorically Constructing the “Working-Woman”

Inventing the Lady Manager: Rhetorically Constructing the “Working-Woman” Julie A. Bokser Abstract: Situated in feminist rhetorical studies, this essay attends to how a select group of women assumed leadership and asserted authority in their work with the 1893 Columbian Exposition. The essay attempts to understand how women became managers and workers by studying the writing and symbolic acts of Bertha Palmer, President of the Board of Lady Managers, and several associates. Using archived correspondence, primary texts, and recent feminist rhetorical methodol- ogy, the essay recovers the women’s rhetorical practices, examines perceptions of gender and leadership, and sketches the challenge of “leaning in” in the rapidly changing working world of the late nineteenth century. Keywords: rhetoric, women’s work, women managers, public memory, performing self, Bertha Palmer, Columbian Exposition “The Board builded better than it knew when it elected her to fill that office. And indeed Congress builded better than it knew when it cre- ated the Board of Lady Managers.” (McDougall 650) * When Bertha Palmer became President of the Board of Lady Managers (BLM) of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, she presided over more than one hundred lady managers, successfully advocated for Congressional fund- ing, supervised the design and building of the Fair’s Woman’s Building, negoti- ated the presence and selection of women judges, and coordinated the display of artifacts made by women from around the world. As noted in contemporary publications, the Board’s goal was to emphasize “the progress of women in a business and professional way,” made possible because “[t]raditional beliefs in regard to what constitutes a fit vocation or avocation for women are dis- appearing” (Yandell 71, Meredith 417). -

Suncoast Empire N T E N NI a Bertha Honoré Palmer, Her Family, and the Rise of Sarasota

2021 SARASOTA COUNTY CENTENNIAL ONE BOOK What is One Book One Community? This is the 18th year the For more than 70 years, the Palmers Sarasota County library made major contributions to the system has participated in the physical and economic growth of "One Book, One Community" the Sarasota district and nurtured program, which started in 1996 its emergence as a cultural center. in Seattle to help foster the Their major achievements included expression of ideas within the successful efforts to increase the UNCOASt community through the shared amount of arable land, provide S mpire love of reading. One Book rail and highways connections, eBertha Honoré Palmer, Her Family, and engages participants in reading revolutionize cattle and hog raising, the Rise of Sarasota and thoughtful conversation by and lead the fight to make Sarasota sponsoring a community-wide a separate county in 1921. Bertha’s reading experience and hosting prowess as a businesswoman programs to explore the became apparent at the time of her themes of the featured book. death in 1918 when her estate was The Book Selection Committee found to be twice as large as the typically spends many weeks one inherited from her husband, reading and reviewing books. Potter Palmer. FRANK A. CASSELL READ THE BOOK, JOIN THE DISCUSSION, SHARE THE STORY. To learn more, go to scgov.net/onebook FRANK CASSELL’S RS OF S A ER E V Y I C 0 E 0 1 C E L Suncoast Empire N T E N NI A Bertha Honoré Palmer, Her Family, and the Rise of Sarasota Sarasota County Public Libraries S OF S AR ER 1660 Ringling Blvd.