Historic Properties Identification Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chicago Venue Portfolio

CHICAGO2016 VENUE PORTFOLIO 1750 W. LAKE STREET CHICAGO, IL 60612 [email protected] 773.880.8044 PARAMOUNTEVENTSCHICAGO.COM Paramount Events is ready to help you plan a spectacular event with a delicious SET menu, but to truly make an impact, the perfect backdrop is absolutely essential. THE We have connections at some of the best venues in Chicago, including The Smith on Lake, our own private space that guarantees dedicated service and personalized attention. SCENE You’re welcome to explore the following pages, but don’t forget – we’re here for you! We know every location inside and out and will be happy to offer our suggestions as a guide. ENJOY! TABLE OF 19th Century Club 1 Garfield Park Conservatory 45 Park West 90 1st Ward at Chop Shop 2 Glessner House Museum 46 Parliament 91 CONTENTS 345 North 3 Goodman Theatre 47 Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum 92 360 Chicago 4 Gruen Galleries 48 Pittsfield Building 93 63rd Street Beach House 5 Harold Washington Library Center 49 Pleasant Home 94 A New Leaf 6 Harris Theatre 50 Portfolio Annex 95 Anita Dee Charters 7 Highland Park Community House 51 Power House 96 Aragon Ballroom 8 Hilton | Asmus Contemporary 52 Prairie Production 97 Artifact Events 9 Hinsdale Community House 53 Primitive Art 98 Auditorium Theatre of Roosevelt University 10 Humboldt Park & Boat House 54 Pritzker Military Museum & Library 99 Baderbräu 11 Ida Noyes Hall at University of Chicago 55 Promontory Point 100 Bentley Gold Coast 12 Ignite Glass Studios 56 Ravenswood Event Center 101 Berger Park 13 International -

VILLAGE WIDE ARCHITECTURAL + HISTORICAL SURVEY Final

VILLAGE WIDE ARCHITECTURAL + HISTORICAL SURVEY Final Survey Report August 9, 2013 Village of River Forest Historic Preservation Commission CONTENTS INTRODUCTION P. 6 Survey Mission p. 6 Historic Preservation in River Forest p. 8 Survey Process p. 10 Evaluation Methodology p. 13 RIVER FOREST ARCHITECTURE P. 18 Architectural Styles p. 19 Vernacular Building Forms p. 34 HISTORIC CONTEXT P. 40 Nineteenth Century Residential Development p. 40 Twentieth Century Development: 1900 to 1940 p. 44 Twentieth Century Development: 1940 to 2000 p. 51 River Forest Commercial Development p. 52 Religious and Educational Buildings p. 57 Public Schools and Library p. 60 Campuses of Higher Education p. 61 Recreational Buildings and Parks p. 62 Significant Architects and Builders p. 64 Other Architects and Builders of Note p. 72 Buildings by Significant Architect and Builders p. 73 SURVEY FINDINGS P. 78 Significant Properties p. 79 Contributing Properties to the National Register District p. 81 Non-Contributing Properties to the National Register District p. 81 Potentially Contributing Properties to a National Register District p. 81 Potentially Non-Contributing Properties to a National Register District p. 81 Noteworthy Buildings Less than 50 Years Old p. 82 Districts p. 82 Recommendations p. 83 INVENTORY P. 94 Significant Properties p. 94 Contributing Properties to the National Register District p. 97 Non-Contributing Properties to the National Register District p. 103 Potentially Contributing Properties to a National Register District p. 104 Potentially Non-Contributing Properties to a National Register District p. 121 Notable Buildings Less than 50 Years Old p. 125 BIBLIOGRAPHY P. 128 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS RIVER FOREST HISTORIC PRESERVATION COMMISSION David Franek, Chair Laurel McMahon Paul Harding, FAIA Cindy Mastbrook Judy Deogracias David Raino-Ogden Tom Zurowski, AIA PROJECT COMMITTEE Laurel McMahon Tom Zurowski, AIA Michael Braiman, Assistant Village Administrator SURVEY TEAM Nicholas P. -

333 North Michigan Buildi·N·G- 333 N

PRELIMINARY STAFF SUfv1MARY OF INFORMATION 333 North Michigan Buildi·n·g- 333 N. Michigan Avenue Submitted to the Conwnission on Chicago Landmarks in June 1986. Rec:ornmended to the City Council on April I, 1987. CITY OF CHICAGO Richard M. Daley, Mayor Department of Planning and Development J.F. Boyle, Jr., Commissioner 333 NORTH MICIDGAN BUILDING 333 N. Michigan Ave. (1928; Holabird & Roche/Holabird & Root) The 333 NORTH MICHIGAN BUILDING is one of the city's most outstanding Art Deco-style skyscrapers. It is one of four buildings surrounding the Michigan A venue Bridge that defines one of the city' s-and nation' s-finest urban spaces. The building's base is sheathed in polished granite, in shades of black and purple. Its upper stories, which are set back in dramatic fashion to correspond to the city's 1923 zoning ordinance, are clad in buff-colored limestone and dark terra cotta. The building's prominence is heightened by its unique site. Due to the jog of Michigan Avenue at the bridge, the building is visible the length of North Michigan Avenue, appearing to be located in the center of the street. ABOVE: The 333 North Michigan Building was one of the first skyscrapers to take advantage of the city's 1923 zoning ordinance, which encouraged the construction of buildings with setback towers. This photograph was taken from the cupola of the London Guarantee Building. COVER: A 1933 illustration, looking south on Michigan Avenue. At left: the 333 North Michigan Building; at right the Wrigley Building. 333 NORTH MICHIGAN BUILDING 333 North Michigan Avenue Architect: Holabird and Roche/Holabird and Root Date of Construction: 1928 0e- ~ 1QQ 2 00 Cft T Dramatically sited where Michigan Avenue crosses the Chicago River are four build ings that collectively illustrate the profound stylistic changes that occurred in American architecture during the decade of the 1920s. -

Chicago Tourist Information 7 August, 2003

Lepton Photon 2003 Chicago Tourist Information 7 August, 2003 XXI International Symposium on Lepton and Photon Interactions at High Energies Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, Batavia, IL USA 11 – 16 August 2003 CHICAGO TOURIST INFORMATION Wednesday 13 August 2003 is a free day at the Lepton Photon 2003 Symposium. The Symposium banquet will be held in the evening at Navy Pier in downtown Chicago. It will begin with a reception at 6:30 p.m., followed by dinner at 7:30 p.m. There will be a lakefront fireworks display right off the pier at 9:30 p.m. Buses will depart from Navy Pier around 10:00 p.m. We hope that many of you will take advantage of the time to visit Chicago. We will run several buses to Chicago in the morning. There will be a few additional buses in the afternoon. Detailed schedules will be available at the beginning of the conference and sign-up for the bus transportation is requested. We have some suggestions for tours you might take or sights you might see depending on your interests. Please be aware that many of the attractions are internationally renowned and, depending on the time of the year and the weather, can be quite crowded and have long waits for admission. In some cases, you can get tickets in advance through the web or Ticketron. All times and fees are for Wednesday, 13 August 2003 and do vary from day to day. More information is available in the materials we have provided in the registration packet and at the official city of Chicago Website: http://www.cityofchicago.org. -

Twenty-Ninth Annual Report

THE ART INSTITUTE MAIN ENTRANCE Lake Front, opposite Adams Street, Chicago 20 PAINTINGS BLAGK.STOM:: HALL. EGYPTIAN 16 ARCHITECTURAL CASTS ASSYRJAN CLASSICAL AND EGYPTIAN GREEK ANTIQUITIES 3 MODERN PHI DIAN 14 MODERN LATER GREEK 12 4 MAIN FLOOR PLAN CHIEFLY CASTS OF SCULPTURE s· Ei ~~ I~ J 45 2 .5 47 46 48 r z - X w 242 44 49 H ONV I"'f.NTAI.. ~TAIRC~E 50 27 UJ ..../ w u a. 33 MUNGER Fl fLD MEMORIAL O LD MASH RS 3 0 31 . COLLfCTION 39 3B 32 ROOM COLLECTION D PAINTINGS Jll 36 34 SECOND FLOOR PLAN CH IEFLY PAINTINGS ' HALL.· OF · .t'\.RCt1lT~C.LVRA._L· casts· 20 · o.ROU!'<Il•I"L.OOR• •ART ·! NSl'fTUTIS.• Ot'• SHOWING SCHOOLROOMS 1../"f THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO TWENTY-NINTH ANNUAL REPORT JUNE I, 1907-JUNE I, 1908 CONTENTS TRUSTEES AND OFFICERS 13 REPORT OF THE TRUSTEES 17 REPORT OF THE TREASURER 33 REPORT OF THE DIRECTOR 37 LisT OF ExHIBITIONS OF 1 907-8 38 LIST OF LECTURES, I 907-8 43 LisT OF PuBLICATIONs, I 907-8 so REPORT OF THE LIBRARIAN 58 LisT OF AcQUISITIONs TO MusEUM 64 LisT OF AcQUISITIONS TO LIBRARY 69 BY-LAWS 83 FoRM oF BEQUEST 89 LisT oF HoNORARY MEMBERs 90 LisT oF GovERNING LIFE M}:MBERS 91 LisT OF GovERNING MEMBERS 92 LIST OF LIFE MEMBERS 95 LIST OF ANNUAL MEMBERS 100 II Trustees of the Art lnstitu te of Chicago 1908-9 EDWARD E. AYER JOHN J. GLESSNER ADOLPHUS C. BARTLETT FRANK W. GUNSAULUS JOHN C. BLACK CHARLES L. -

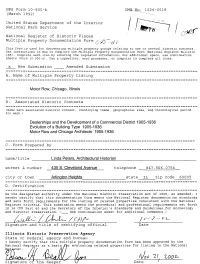

A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Motor Row, Chicago, Illinois Street

NFS Form 10-900-b OMR..Np. 1024-0018 (March 1992) / ~^"~^--.~.. United States Department of the Interior National Park Service / / v*jf f ft , I I / / National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form /..//^' -A o C_>- f * f / *•• This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. x New Submission Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Motor Row, Chicago, Illinois B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) Dealerships and the Development of a Commercial District 1905-1936 Evolution of a Building Type 1905-1936 Motor Row and Chicago Architects 1905-1936 C. Form Prepared by name/title _____Linda Peters. Architectural Historian______________________ street & number 435 8. Cleveland Avenue telephone 847.506.0754 city or town ___Arlington Heights________________state IL zip code 60005 D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation. -

Mounted on a Pedestal: Bertha Honoré Palmer Hope L

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 11-8-2007 Mounted on a Pedestal: Bertha Honoré Palmer Hope L. Black University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Black, Hope L., "Mounted on a Pedestal: Bertha Honoré Palmer" (2007). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/637 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mounted on a Pedestal: Bertha Honoré Palmer by Hope L. Black A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Liberal Arts Department of Humanities College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida CoMajor Professor: Gary Mormino, Ph.D. CoMajor Professor: Raymond Arsenault, Ph.D. Julie Armstrong, Ph.D. Date of Approval: November 8, 2007 Keywords: World’s Columbian Exposition, Meadowsweet Pastures, Great Chicago Fire, Manatee County, Seaboard Air Line Railroad © Copyright 2007, Hope L. Black Acknowledgements With my heartfelt appreciation to Professors Gary Mormino and Raymond Arsenault who allowed me to embark on this journey and encouraged and supported me on every path; to Greta ScheidWells who has been my lifeline; to Professors Julie Armstrong, Christopher Meindl, and Daryl Paulson, who enlightened and inspired me; to Ann Shank, Mark Smith, Dan Hughes, Lorrie Muldowney and David Baber of the Sarasota County History Center who always took the time to help me; to the late Rollins E. -

2012 Appropriation Ordinance 10.27.11.Xlsx

2012 Budget Appropriations 3 4 Table of Contents Districtwide 8 Humboldt Park……………...…....………….…… 88 Districtwide Summary 9 Kedvale Park……………...…....………….…….. 90 Communications……………….....….……...….… 10 Kelly (Edward J.) Park……………...…....……91 Community Recreation ……………..……………. 11 Kennicott Park……………...…....………….…… 92 Facilities Management - Specialty Trades……………… 29 Kenwood Community Park……………...…. 93 Grant Park Music Festival………...……….…...… 32 La Follette Park……………...…....………….…… 94 Human Resources…………..…….…………....….. 33 Lake Meadows Park ……………...…....………96 Natural Resources……………….……….……..….. 34 Lakeshore……………...…....………….…….. 97 Park Services - Permit Enforcement 38 Le Claire-Hearst Community Center……… 98 Madero School Park……………...…....……… 99 Central Region 40 McGuane Park……………...…....………….…… 100 Central Region Parks 41 McKinley Park……………………………....…… 103 Central Region – Summary ...……...……................. 43 Moore Park……………...…....………….…….. 105 Central Region – Administration……….................... 44 National Teachers Academy……………...… 106 Altgeld Park………………………………………… 46 Northerly Island……………...…....………….… 108 Anderson Playground Park……….……...………….. 47 Orr Park………………………………..…..…..… 109 Archer Park……...................................................... 48 Piotrowski Park……………...…....………….… 110 Armour Square Park……........................................... 49 Pulaski Park……………...…....………….…….. 113 Augusta Playground……........................................... 50 Seward Park ……………...…....………….…….. 114 Austin Town Hall……............................................... -

Four Corners

ctbuh.org/papers Title: Chicago – “The” Four Corners Author: Michael Kaufman, Partner, Goettsch Partners Subjects: Building Case Study Conservation/Restoration/Maintenance History, Theory & Criticism Retrofit Sustainability/Green/Energy Keywords: Adaptability Renovation Retrofit Publication Date: 2015 Original Publication: Global Interchanges: Resurgence of the Skyscraper City Paper Type: 1. Book chapter/Part chapter 2. Journal paper 3. Conference proceeding 4. Unpublished conference paper 5. Magazine article 6. Unpublished © Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat / Michael Kaufman Chicago – “The” Four Corners Abstract Michael F. Kaufman Partner, AIA, LEED AP GP was selected to Renovate or Adapt “The” prime corners of Michigan Avenue on both sides Goettsch Partners, of the Chicago River, all within a two year period. The buildings include The Wrigley Building, Chicago, USA The London Guarantee Building, 333 N. Michigan Avenue and 401 N. Michigan Avenue. Each received differing levels of work ranging from a lobby renovation to a full gut-rehab. The use of the London Guarantee Building is being changed from office to a 450-key hotel including a new At Goettsch Partners, Michael Kaufman, AIA, serves as a managing partner on corporate and commercial office addition. The three others respond to the growing demand for up-to-date office space and prime buildings, hotels, academic and institutional facilities, and retail in historic buildings with un-paralleled views of the Chicago River and Michigan Avenue. renovation and repositioning assignments. Recent work includes the adaptive reuse of the lower levels of Mies van der Rohe’s IBM Building as the Langham Chicago Keywords: Adaptive Re-Use, Historic Buildings, Real Estate Investment, Renovation, hotel, JW Marriott in Grand Rapids, Michigan; Grand Hyatt hotels in Brazil, Colombia and India. -

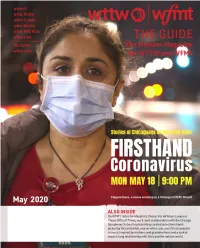

Wwciguide May 2020.Pdf

From the President & CEO The Guide The Member Magazine Dear Member, for WTTW and WFMT Thank you for your viewership, listenership, and continued support of WTTW and Renée Crown Public Media Center 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue WFMT. Now more than ever, we believe it is vital that you can turn to us for trusted Chicago, Illinois 60625 news and information, and high quality educational and entertaining programming whenever and wherever you want it. We have developed our May schedule with this Main Switchboard in mind. (773) 583-5000 Member and Viewer Services On WTTW, explore the personal, firsthand perspectives of people whose lives (773) 509-1111 x 6 have been upended by COVID-19 in Chicago in FIRSTHAND: Coronavirus. This new series of stories produced and released on wttw.com and our social media channels Websites wttw.com has been packaged into a one-hour special for television that will premiere on wfmt.com May 18 at 9:00 pm. Also, settle in for the new two-night special Asian Americans to commemorate Asian Pacific American Heritage Month. As America becomes more Publisher diverse, and more divided while facing unimaginable challenges, this film focuses a Anne Gleason Art Director new lens on U.S. history and the ongoing role that Asian Americans have played. On Tom Peth wttw.com, discover and learn about Chicago’s Japanese Culture Center established WTTW Contributors Julia Maish in 1977 in Chicago by Aikido Shihan (Teacher of Teachers) and Zen Master Fumio Lisa Tipton Toyoda to make the crafts, philosophical riches, and martial arts of Japan available WFMT Contributors to Chicagoans. -

Revised Agenda Meeting Of

REVISED AGENDA MEETING OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF SOUTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY Thursday, December 13, 2018 Approximately 10 a.m. Ballroom B Student Center Southern Illinois University Carbondale Call to Order by Chair Pledge of Allegiance Roll Call Approval of Minutes of the Meetings Held September 12 and 13, 2018, and November 9, 2018 BOARD OF TRUSTEES ACTIVITIES A. Trustee Reports B. Committee Reports Executive Committee EXECUTIVE OFFICER REPORTS C. President, Southern Illinois University D. Chancellor, Southern Illinois University Carbondale E. Chancellor, Southern Illinois University Edwardsville F. Dean and Provost, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine PUBLIC COMMENTS AND QUESTIONS RECEIPT OF INFORMATION AND NOTICE ITEMS G. Report of Purchase Orders and Contracts, August, September and October 2018, SIUC H. Report of Purchase Orders and Contracts, August, September and October 2018, SIUE RATIFICATION OF PERSONNEL MATTERS I. Changes in Faculty-Administrative Payroll – SIUC J. Changes in Faculty-Administrative Payroll – SIUE ITEMS RECOMMENDED FOR APPROVAL BY THE PRESIDENT K. Approval of Change to 5 Policies of the Board A, Budgets and Article III, Section 3 of Board Bylaws L. Approval of Administrative Reorganization of Academic Units and the Use of the Reasonable and Moderate Extension Process of the Illinois Board of Higher Education, SIUC M. Approval of Purchase: Constituent Relations Management Software, Carbondale Campus, SIUC N. Project and Budget Approval and Award of Contract: Turf Replacement Saluki Stadium, Carbondale Campus, SIUC O. Approval of Purchase: Aircraft for Aviation Flight Program, SIUC P. Approval of Purchase: Electrical Supplies, Carbondale Campus, SIUC Q. Award of Contract: Medical Instruction Facility, Lobby Renovations, School of Medicine Campus, SIUC R. -

Permit Review Committee Report

MINUTES OF THE MEETING COMMISSION ON CHICAGO LANDMARKS December 3, 2009 The Commission on Chicago Landmarks held a regular meeting on December 3, 2009. The meeting was held at City Hall, 121 N. LaSalle St., Room 201-A, Chicago, Illinois. The meeting began at 12:55 p.m. PRESENT: David Mosena, Chairman John Baird, Secretary Yvette Le Grand Christopher Reed Patricia A. Scudiero, Commissioner Department of Zoning and Planning Ben Weese ABSENT: Phyllis Ellin Chris Raguso Edward Torrez Ernest Wong ALSO PRESENT: Brian Goeken, Deputy Commissioner, Department of Zoning and Planning, Historic Preservation Division Patricia Moser, Senior Counsel, Department of Law Members of the Public (The list of those in attendance is on file at the Commission office.) A tape recording of this meeting is on file at the Department of Zoning and Planning, Historic Preservation Division offices, and is part of the permanent public record of the regular meeting of the Commission on Chicago Landmarks. Chairman Mosena called the meeting to order. 1. Approval of the Minutes of the November 5, 2009, Regular Meeting Motioned by Baird, seconded by Weese. Approved unanimously. (6-0) 2. Preliminary Landmark Recommendation UNION PARK HOTEL WARD 27 1519 W. Warren Boulevard Resolution to recommend preliminary landmark designation for the UNION PARK HOTEL and to initiate the consideration process for possible designation of the building as a Chicago Landmark. The support of Ald. Walter Burnett (27th Ward), within whose ward the building is located, was noted for the record. Motioned by Reed, seconded by Weese. Approved unanimously. (6-0) 3. Report from a Public Hearing and Final Landmark Recommendation to City Council CHICAGO BLACK RENAISSANCE LITERARY MOVEMENT Lorraine Hansberry House WARD 20 6140 S.