Mounted on a Pedestal: Bertha Honoré Palmer Hope L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wwciguide May 2020.Pdf

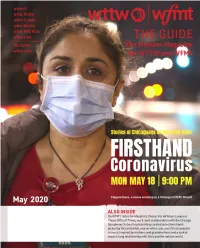

From the President & CEO The Guide The Member Magazine Dear Member, for WTTW and WFMT Thank you for your viewership, listenership, and continued support of WTTW and Renée Crown Public Media Center 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue WFMT. Now more than ever, we believe it is vital that you can turn to us for trusted Chicago, Illinois 60625 news and information, and high quality educational and entertaining programming whenever and wherever you want it. We have developed our May schedule with this Main Switchboard in mind. (773) 583-5000 Member and Viewer Services On WTTW, explore the personal, firsthand perspectives of people whose lives (773) 509-1111 x 6 have been upended by COVID-19 in Chicago in FIRSTHAND: Coronavirus. This new series of stories produced and released on wttw.com and our social media channels Websites wttw.com has been packaged into a one-hour special for television that will premiere on wfmt.com May 18 at 9:00 pm. Also, settle in for the new two-night special Asian Americans to commemorate Asian Pacific American Heritage Month. As America becomes more Publisher diverse, and more divided while facing unimaginable challenges, this film focuses a Anne Gleason Art Director new lens on U.S. history and the ongoing role that Asian Americans have played. On Tom Peth wttw.com, discover and learn about Chicago’s Japanese Culture Center established WTTW Contributors Julia Maish in 1977 in Chicago by Aikido Shihan (Teacher of Teachers) and Zen Master Fumio Lisa Tipton Toyoda to make the crafts, philosophical riches, and martial arts of Japan available WFMT Contributors to Chicagoans. -

INTERVIEW with PAUL DURBIN Mccurry Interviewed by Betty J. Blum Compiled Under the Auspices of the Chicago Architects Oral Histo

INTERVIEW WITH PAUL DURBIN McCURRY Interviewed by Betty J. Blum Compiled under the auspices of the Chicago Architects Oral History Project The Ernest R. Graham Study Center for Architectural Drawings Department of Architecture The Art Institute of Chicago Copyright © 1988 Revised Edition Copyright © 2005 The Art Institute of Chicago This manuscript is hereby made available to the public for research purposes only. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publication, are reserved to the Ryerson and Burnham Libraries of The Art Institute of Chicago. No part of this manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of The Art Institute of Chicago. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface iv Preface to the Revised Edition vi Outline of Topics vii Oral History 1 Selected References 150 Curriculum Vitae 151 Index of Names and Buildings 152 iii PREFACE On January 23, 24, and 25, 1987, I met with Paul McCurry in his home in Lake Forest, Illinois, where we recorded his memoirs. During Paul's long career in architecture he has witnessed events and changes of prime importance in the history of architecture in Chicago of the past fifty years, and he has known and worked with colleagues, now deceased, of major interest and significance. Paul retains memories dating back to the 1920s which give his recollections and judgments special authority. Moreover, he speaks as both an architect and an educator. Our recording sessions were taped on four 90-minute cassettes that have been transcribed, edited and reviewed for clarity and accuracy. This transcription has been minimally edited in order to maintain the flow, spirit and tone of Paul's original thought. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

SILVER SPRINGS: THE FLORIDA INTERIOR IN THE AMERICAN IMAGINATION By THOMAS R. BERSON A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Thomas R. Berson 2 To Mom and Dad Now you can finally tell everyone that your son is a doctor. 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my entire committee for their thoughtful comments, critiques, and overall consideration. The chair, Dr. Jack E. Davis, has earned my unending gratitude both for his patience and for putting me—and keeping me—on track toward a final product of which I can be proud. Many members of the faculty of the Department of History were very supportive throughout my time at the University of Florida. Also, this would have been a far less rewarding experience were it not for many of my colleagues and classmates in the graduate program. I also am indebted to the outstanding administrative staff of the Department of History for their tireless efforts in keeping me enrolled and on track. I thank all involved for the opportunity and for the ongoing support. The Ray and Mitchum families, the Cheatoms, Jim Buckner, David Cook, and Tim Hollis all graciously gave of their time and hospitality to help me with this work, as did the DeBary family at the Marion County Museum of History and Scott Mitchell at the Silver River Museum and Environmental Center. David Breslauer has my gratitude for providing a copy of his book. -

French Impressionist and Post Impressionist Paintings from the Collections of Mrs. Bertha Palmer Thorne and Mr. Gordon Palmer

FRENCH IMPRESSIONIST AND POST IMPRESSIONIST PAINTINGS from the Collections of MRS. BERTHA PALMER THORHE AND MR. GORDOH PALMER CATALOGUE WALKER ART MUSEUM Bowdoin College Bninf^wick, Maine May 11 ' June 17, 1962 Mrs. Bertha Palmer Thorne and Gordon Palmer are grandchildren of Mrs. Potter Palmer of Chicago who, in 1889, was one of the first Americans to introduce French Impressionst Painting to this country. While the greatest portion of Mrs. Palmer's collection is in the Art Institute of Chicago, many of the pictures in this exhibition were among those acquired by her. To this original group, our lenders have since added several important examples ranging in time and taste from Bou' din's La Plage to Picasso's Two Pigeons. It is a privilege for the Walker Art Museum of Bowdoin College to be able to present to a new audience such a distinguished group of pictures, many of which were the first of their kind to reach our shores. M. S. S. Lent by Mrs. Bertha Palmer Thorne Jean'Antoine Houdon (1714-1828), Portrait of a Little Girl, bronze sculpture Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot (1796' 1875), Trois Jeunes Filles pres d'un Arbre, oil Eugene Boudin (1824-1898), La Plage, oil Edouard Manet (1832-1883), Portrait of Berthe Morisot, lithograph Hilaire Germaine Edgar Degas (1834-1917), Mile. Wol\ons\a, etching Degas, Interior with Dancers^ monotype Henri Fantin-Latour (1836-1904), Women Embroidering^ lithograph Alfred Sisley (1839-1899), Landscape, oil Paul Cezanne (1839-1906), The Indwell, watercolor Cezanne, The ^uarrv, watercolor Cezanne, Mont St. -

[OWNER of PROPERTY Contact: Joseph A

Form No. 10-30*0 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS HISTORIC Marshall Field & Company Store AND/OR COMMON Marshall Field & Company Store HLOCATION STREET& NUMBER ill North State Street _NOT FOR PUBLICATION 7 CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Chicago . _. VICINITY OF. STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Illinois 17 Cook 031 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC X_OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE _ MUSEUM X_BUiLDiNG(S) ^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED X_COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE _ ENTERTAINMENT _ RELIGIOUS —OBJECT . _|N PROCESS X_YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _BEING CONSIDERED _YE.S: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: t- • < [OWNER OF PROPERTY Contact: Joseph A. Burnham, President NAMEMarshall Field & Company STREET & NUMBER 25 East Washington Street CITY. TOWN STATE Chicago VICINITY OF Illinois LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC Recorder of Deeds Office, City Hall and County Building STREET & NUMBER 118 North Clark Street CITY, TOWN STATE Chicago Illinois 1 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Chicago Landmark Structure Inventory; Illinois Land and Historic Site DATE survey FEDERAL X-STATE COUNTY X-LOCAL 197^,= ———1975 DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Chicago Landmarks -

The Woman's Building of the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893

The Invisible Triumph: The Woman's Building of the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893 JAMES V. STRUEBER Ohio State University, AT1 JOHANNA HAYS Auburn University INTRODUCTION from Engineering Magazine, The World's Columbian Exposition (WCE) was the first world exposition outside of Europe and was to Thus has Chicago gloriously redeemed the commemorate the four hundredth anniversary of obligations incurred when she assumed the Columbus reaching the New World. The exhibition's task of building a World's Fair. Chicago's planners aimed at exceeding the fame of the 1889 businessmen started out to prepare for a Paris World Exposition in physical size, scope of finer, bigger, and more successful enter- accomplishment, attendance, and profitability.' prise than the world had ever seen in this With 27 million attending equaling approximately line. The verdict of the jury of the nations 40% of the 1893 US population, they exceeded of the earth, who have seen it, is that it the Paris Exposition in all accounts. This was partly is unquestionably bigger and undoubtedly accomplished by being open on Sundays-a much finer, and now it is assuredly more success- debated moral issue-the attraction of the newly ful. Great is Chicago, and we are prouder invented Ferris wheel, cheap quick nationwide than ever of her."5 transportation provided by the new transcontinental railroad system all helped to make a very successful BACKGROUND financial plans2Surprisingly, the women's contribu- tion to the exposition, which included the Woman's Labeled the "White City" almost immediately, for Building and other women's exhibits accounted for the arrangement of the all-white neo-Classical and 57% of total exhibits at the exp~sition.~In addition neo-High Renaissance architectural style buildings railroad development to accommodate the exposi- around a grand court and fountain poolI6 the WCE tion, set the heart of American trail transportation holds an ironic position in American history. -

Property Rights in Reclaimed Land and the Battle for Streeterville

Columbia Law School Scholarship Archive Faculty Scholarship Faculty Publications 2013 Contested Shore: Property Rights in Reclaimed Land and the Battle for Streeterville Joseph D. Kearney Thomas W. Merrill Columbia Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Environmental Law Commons, and the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation Joseph D. Kearney & Thomas W. Merrill, Contested Shore: Property Rights in Reclaimed Land and the Battle for Streeterville, 107 NW. U. L. REV. 1057 (2013). Available at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/383 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Scholarship Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright 2013 by Northwestern University School of Law Printed in U.S.A. Northwestern University Law Review Vol. 107, No. 3 Articles CONTESTED SHORE: PROPERTY RIGHTS IN RECLAIMED LAND AND THE BATTLE FOR STREETERVILLE Joseph D. Kearney & Thomas W. Merrill ABSTRACT-Land reclaimed from navigable waters is a resource uniquely susceptible to conflict. The multiple reasons for this include traditional hostility to interference with navigable waterways and the weakness of rights in submerged land. In Illinois, title to land reclaimed from Lake Michigan was further clouded by a shift in judicial understanding in the late nineteenth century about who owned the submerged land, starting with an assumption of private ownership but eventually embracing state ownership. The potential for such legal uncertainty to produce conflict is vividly illustrated by the history of the area of Chicago known as Streeterville, the area of reclaimed land along Lake Michigan north of the Chicago River and east of Michigan Avenue. -

World's Fair Women and Wives of Prominent Officials Connected With

.Urt5 WOBEN. ! LIBRARY OF^CONGRESS. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA. A SOUVENIR OF "^orlb's o fair © ^omeri AXD WIVES OF PROMINENT OFFICIALS CONXECTED WITH THE Wopid s Oolumblan Qxposition. CHICAGO THE BI^OCHKR COMPANY 1892 Copyright T8q2 BY Josephine D. Hilu PREFACE. .V N attempting to select the most prominent, or most beautiful Jl women connected with the World's Columbian Exposition, the same difficult}' would be encountered, as would be, should one enter Superintendent Thorp's flower-garden on the Exposi- tion grounds and strive to select a bouquet of only the most attrac- tive and beautiful flowers. The author discovered at the outset that the task of chosing from the galax}' of charming and bril- liant women who compose the Board of Lady INIanagers of the World's Columbian Commission, or selecting the loveliest from those who rule the hearthstones of the prominent officials, would be most difficult and delicate. It it needless to say the thought was abandoned, and in the garden where this little bouquet was gathered, we have left lilies just as fair, and roses just as magni- ficent, violets just as sweet, and forget-me-nots just as lovable. We trust that a charitable public will understand and appre- ciate the intent to only have a dainty little souvenir book worthy of the occasion. • r. D. H. PART I. Mrs. Bertha M. Honore Paemer. Mrs. Susan Gaee Cooke. Mrs. Raeph Trautmanx. INlRS. Charees Price. Mrs. Susax R. Asheey. INIrs. Nancy Huston Banks. Mrs. Heeen Morton Barker. Mrs. Marcia Louise Gould. Mrs. Gen. John A. -

Historic Properties Identification Report

Section 106 Historic Properties Identification Report North Lake Shore Drive Phase I Study E. Grand Avenue to W. Hollywood Avenue Job No. P-88-004-07 MFT Section No. 07-B6151-00-PV Cook County, Illinois Prepared For: Illinois Department of Transportation Chicago Department of Transportation Prepared By: Quigg Engineering, Inc. Julia S. Bachrach Jean A. Follett Lisa Napoles Elizabeth A. Patterson Adam G. Rubin Christine Whims Matthew M. Wicklund Civiltech Engineering, Inc. Jennifer Hyman March 2021 North Lake Shore Drive Phase I Study Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... v 1.0 Introduction and Description of Undertaking .............................................................................. 1 1.1 Project Overview ........................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 NLSD Area of Potential Effects (NLSD APE) ................................................................................... 1 2.0 Historic Resource Survey Methodologies ..................................................................................... 3 2.1 Lincoln Park and the National Register of Historic Places ............................................................ 3 2.2 Historic Properties in APE Contiguous to Lincoln Park/NLSD ....................................................... 4 3.0 Historic Context Statements ........................................................................................................ -

International House Entrance May Have Significance As Part of the Body of Gardner Dailey‘S Work

Focused Project Evaluation: Entry and Laundry Room International House U.C. Berkeley Berkeley, California December 14, 2011 Background and Introduction The Board of Directors of the International House is considering making alterations to the House, including modifications to the front entry and to the laundry room/elevator lobby. Carey & Co. prepared the following focused project evaluation concentrating on the areas of work. This report is based upon conversations with Greg Rodolari, Facilities Manager of the International House, William Riggs, Principal Planner, Physical and Environmental Planning at U.C. Berkeley, and Emily Marthinsen, Assistant Vice Chancellor at U.C. Berkeley. This document will determine whether the project is in compliance with the Secretary of the Interior‟s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties (Standards). The International House, constructed in 1930, was designed by George W. Kelham in the Spanish Colonial Revival Style for the UC Regents. It was identified in the UC Berkeley 2020 Long Range Development Plan, Environmental Impact Report as a secondary historical resource – presumed to be historically or culturally significant unless evidence supports a contrary finding. Built into the side of a hill, the eight-story concrete structure serves as a residence hall with rooms for residents, a dinning room, café and several large public gathering rooms. Facing west onto Piedmont Avenue, the main entrance to the building is a one-story enclosed entry flanked on each side by three-story gable end projections, creating an outdoor courtyard. A three-story block rises behind the entrance and the rest of the building gradually steps up with the slope of the hill. -

Henry Ives Cobb: Forgotten Innovator of the Chica~O School

Henry Ives Cobb: Forgotten Innovator of the Chica~o School Kari11 M.£. Alexis The Street in Cairo at the \\orld ·s Columbian Exposi the Water Tower associated Potter Palmer with the spirit of tion of 1893 and the Chicago Opera House , 1884- 5 (Figures Chicago. Cobb masterfully exploited the symbolic potential 1- 3), may seem to have linle in common, for the fonner is of architectural fonn. and he would continue 10 do this an American's vision of a far.off and exotic land while the throughout his career. The immediate success of the Potter lancr is a stripped-down commercial building. Yet. both Palmer Mansion made this residence a Chicago landmark were erected in Chicago during the tum-of-the-century and helped establish Cobb as an important local archi1ec1. 10 period and both were designed by Henry Ives Cobb . The During the 1880s he worked with one partner. and his finn fact that both were destroyed I partially explains why one of became well known for its many mansions and domestic the most successful architects of the Chicago School and the commissions. American Renaissance has nearly been forgoncn. Admired Soon after the completion of the Potter Palmer Man by the great critic Montgomery Schuyler and acknowledged sion, Cobb received another important commission-this as an innovator in the use of metal skeletal systems.' Cobb one for a tall, commercial building, the Chicago Opera. has rarely been the subject of recent hislorians.J To further 1884-5 (Figure 3). Erected only a few months after William complicate the issue, virn,ally no records or correspondence Le Baron Jenney·s Homes Insurance Building, the Chicago from his office remain because most, if not all, of Cobb's Opera was a ten-story. -

Cultural Resource Assessment Survey Lakewood Ranch Boulevard Extension Sarasota County, Florida

CULTURAL RESOURCE ASSESSMENT SURVEY LAKEWOOD RANCH BOULEVARD EXTENSION SARASOTA COUNTY, FLORIDA Performed for: Kimley-Horn 1777 Main Street, Suite 200 Sarasota, Florida 34326 Prepared by: Florida’s First Choice in Cultural Resource Management Archaeological Consultants, Inc. 8110 Blaikie Court, Suite A Sarasota, Florida 34240 (941) 379-6206 Toll Free: 1-800-735-9906 June 2016 CULTURAL RESOURCE ASSESSMENT SURVEY LAKEWOOD RANCH BOULEVARD EXTENSION SARASOTA COUNTY, FLORIDA Performed for: Kimley-Horn 1777 Main Street, Suite 200 Sarasota, Florida 34326 By: Archaeological Consultants, Inc. 8110 Blaikie Court, Suite A Sarasota, Florida 34240 Marion M. Almy - Project Manager Lee Hutchinson - Project Archaeologist Katie Baar - Archaeologist Thomas Wilson - Architectural Historian June 2016 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A cultural resource assessment survey (CRAS) of the Lakewood Ranch Boulevard Extension, in Sarasota, Florida, was performed by Archaeological Consultants, Inc (ACI). The purpose of this survey was to locate and identify any cultural resources within the project area and to assess their significance in terms of eligibility for listing in the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) and the Sarasota County Register of Historic Places (SCRHP). This report is in compliance with the Historic Preservation Chapter of Apoxsee and Article III, Chapter 66 (Sub-Section 66-73) of the Sarasota County Code, as well as with Chapters 267 and 373, Florida Statutes (FS), Florida’s Coastal Management Program, and implementing state regulations regarding possible impact to significant historical properties. The report also meets specifications set forth in Chapter 1A-46, Florida Administrative Code (FAC) (revised August 21, 2002). Background research, including a review of the Florida Master Site File (FMSF), and the NRHP indicated no prehistoric archaeological sites were recorded in the project area.