University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The News Media Industry Defined

Spring 2006 Industry Study Final Report News Media Industry The Industrial College of the Armed Forces National Defense University Fort McNair, Washington, D.C. 20319-5062 i NEWS MEDIA 2006 ABSTRACT: The American news media industry is characterized by two competing dynamics – traditional journalistic values and market demands for profit. Most within the industry consider themselves to be journalists first. In that capacity, they fulfill two key roles: providing information that helps the public act as informed citizens, and serving as a watchdog that provides an important check on the power of the American government. At the same time, the news media is an extremely costly, market-driven, and profit-oriented industry. These sometimes conflicting interests compel the industry to weigh the public interest against what will sell. Moreover, several fast-paced trends have emerged within the industry in recent years, driven largely by changes in technology, demographics, and industry economics. They include: consolidation of news organizations, government deregulation, the emergence of new types of media, blurring of the distinction between news and entertainment, decline in international coverage, declining circulation and viewership for some of the oldest media institutions, and increased skepticism of the credibility of “mainstream media.” Looking ahead, technology will enable consumers to tailor their news and access it at their convenience – perhaps at the cost of reading the dull but important stories that make an informed citizenry. Changes in viewer preferences – combined with financial pressures and fast paced technological changes– are forcing the mainstream media to re-look their long-held business strategies. These changes will continue to impact the media’s approach to the news and the profitability of the news industry. -

The Theme Park As "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," the Gatherer and Teller of Stories

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2018 Exploring a Three-Dimensional Narrative Medium: The Theme Park as "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," The Gatherer and Teller of Stories Carissa Baker University of Central Florida, [email protected] Part of the Rhetoric Commons, and the Tourism and Travel Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Baker, Carissa, "Exploring a Three-Dimensional Narrative Medium: The Theme Park as "De Sprookjessprokkelaar," The Gatherer and Teller of Stories" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 5795. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5795 EXPLORING A THREE-DIMENSIONAL NARRATIVE MEDIUM: THE THEME PARK AS “DE SPROOKJESSPROKKELAAR,” THE GATHERER AND TELLER OF STORIES by CARISSA ANN BAKER B.A. Chapman University, 2006 M.A. University of Central Florida, 2008 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, FL Spring Term 2018 Major Professor: Rudy McDaniel © 2018 Carissa Ann Baker ii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the pervasiveness of storytelling in theme parks and establishes the theme park as a distinct narrative medium. It traces the characteristics of theme park storytelling, how it has changed over time, and what makes the medium unique. -

Prohibited Waterbodies for Removal of Pre-Cut Timber

PROHIBITED WATERBODIES FOR REMOVAL OF PRE-CUT TIMBER Recovery of pre-cut timber shall be prohibited in those waterbodies that are considered pristine due to water quality or clarity or where the recovery of pre-cut timber will have a negative impact on, or be an interruption to, navigation or recreational pursuits, or significant cultural resources. Recovery shall be prohibited in the following waterbodies or described areas: 1. Alexander Springs Run 2. All Aquatic Preserves designated under chapter 258, F.S. 3. All State Parks designated under chapter 258, F.S. 4. Apalachicola River between Woodruff lock to I-10 during March, April and May 5. Chipola River within state park boundaries 6. Choctawhatchee River from the Alabama Line 3 miles south during the months of March, April and May. 7. Econfina River from Williford Springs south to Highway 388 in Bay County. 8. Escambia River from Chumuckla Springs to a point 2.5 miles south of the springs 9. Ichetucknee River 10. Lower Suwannee River National Refuge 11. Merritt Mill Pond from Blue Springs to Hwy. 90 12. Newnan’s Lake 13. Ocean Pond – Osceola National Forest, Baker County 14. Oklawaha River from the Eureka Dam to confluence with Silver River 15. Rainbow River 16. Rodman Reservoir 17. Santa Fe River, 3 Miles above and below Ginnie Springs 18. Silver River 19. St. Marks from Natural Bridge Spring to confluence with Wakulla River 20. Suwannee River within state park boundaries 21. The Suwannee River from the Interstate 10 bridge north to the Florida Sheriff's Boys Ranch, inclusive of section 4, township 1 south, range 13 east, during the months of March, April and May. -

The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1

Contents Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances .......... 2 February 7–March 20 Vivien Leigh 100th ......................................... 4 30th Anniversary! 60th Anniversary! Burt Lancaster, Part 1 ...................................... 5 In time for Valentine's Day, and continuing into March, 70mm Print! JOURNEY TO ITALY [Viaggio In Italia] Play Ball! Hollywood and the AFI Silver offers a selection of great movie romances from STARMAN Fri, Feb 21, 7:15; Sat, Feb 22, 1:00; Wed, Feb 26, 9:15 across the decades, from 1930s screwball comedy to Fri, Mar 7, 9:45; Wed, Mar 12, 9:15 British couple Ingrid Bergman and George Sanders see their American Pastime ........................................... 8 the quirky rom-coms of today. This year’s lineup is bigger Jeff Bridges earned a Best Actor Oscar nomination for his portrayal of an Courtesy of RKO Pictures strained marriage come undone on a trip to Naples to dispose Action! The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1 .......... 10 than ever, including a trio of screwball comedies from alien from outer space who adopts the human form of Karen Allen’s recently of Sanders’ deceased uncle’s estate. But after threatening each Courtesy of Hollywood Pictures the magical movie year of 1939, celebrating their 75th Raoul Peck Retrospective ............................... 12 deceased husband in this beguiling, romantic sci-fi from genre innovator John other with divorce and separating for most of the trip, the two anniversaries this year. Carpenter. His starship shot down by U.S. air defenses over Wisconsin, are surprised to find their union rekindled and their spirits moved Festival of New Spanish Cinema .................... -

Blue-Green Algal Bloom Weekly Update Reporting March 26 - April 1, 2021

BLUE-GREEN ALGAL BLOOM WEEKLY UPDATE REPORTING MARCH 26 - APRIL 1, 2021 SUMMARY There were 12 reported site visits in the past seven days (3/26 – 4/1), with 12 samples collected. Algal bloom conditions were observed by the samplers at seven of the sites. The satellite imagery for Lake Okeechobee and the Caloosahatchee and St. Lucie estuaries from 3/30 showed low bloom potential on visible portions of Lake Okeechobee or either estuary. The best available satellite imagery for the St. Johns River from 3/26 showed no bloom potential on Lake George or visible portions of the St. Johns River; however, satellite imagery from 3/26 was heavily obscured by cloud cover. Please keep in mind that bloom potential is subject to change due to rapidly changing environmental conditions or satellite inconsistencies (i.e., wind, rain, temperature or stage). On 3/29, South Florida Water Management District staff collected a sample from the C43 Canal – S77 (Upstream). The sample was dominated by Microcystis aeruginosa and had a trace level [0.42 parts per billion (ppb)] of microcystins detected. On 3/29, Florida Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) staff collected a sample from Lake Okeechobee – S308 (Lakeside) and at the C44 Canal – S80. The Lake Okeechobee – S308 (Lakeside) sample was dominated by Microcystis aeruginosa and had a trace level (0.79 ppb) of microcystins detected. The C44 Canal – S80 sample had no dominant algal taxon and had a trace level (0.34 ppb) of microcystins detected. On 3/29, Highlands County staff collected a sample from Huckleberry Lake – Canal Entrance. -

Small Town Happenings: Local News Values and the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Local Newspapers

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2021 Small Town Happenings: Local News Values and the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Local Newspapers Dana Armstrong Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Journalism Studies Commons, and the Social Media Commons Recommended Citation Armstrong, Dana, "Small Town Happenings: Local News Values and the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Local Newspapers" (2021). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 1711. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/1711 This Honors Thesis -- Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Small Town Happenings: Local News Values and the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Local Newspapers A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies from William & Mary by Dana Ellise Armstrong Accepted for ______Honors_________ (Honors) _________________________________________ Elizabeth Losh, Director Brian Castleberry _________________________________________ Brian Castleberry Jon Pineda _________________________________________ Jon Pineda Candice Benjes-Small _____________________________ Candice Benjes-Small ______________________________________ Stephanie Hanes-Wilson Williamsburg, VA May 14, 2021 Acknowledgements There is nothing quite like finding the continued motivation to work on a thesis during a pandemic. I would like to extend a huge thank you to all of the people who provided me moral support and guidance along the way. To my thesis and major advisor, Professor Losh, thank you for your edits and cheerleading to get me through the writing process and my self-designed journalism major. -

Silver Springs and Upper Silver River and Rainbow Spring Group and Rainbow River Basin BMAP

Silver Springs and Upper Silver River and Rainbow Spring Group and Rainbow River Basin Management Action Plan Division of Environmental Assessment and Restoration Water Quality Restoration Program Florida Department of Environmental Protection with participation from the Silver and Rainbow Stakeholders June 2018 2600 Blair Stone Rd. Tallahassee, FL 32399 floridadep.gov Silver Springs and Upper Silver River and Rainbow Spring Group and Rainbow River Basin Management Action Plan, June 2018 Acknowledgments The Florida Department of Environmental Protection adopted the Basin Management Action Plan by Secretarial Order as part of its statewide watershed management approach to restore and protect Florida's water quality. The plan was developed in coordination with stakeholders, identified below, with participation from affected local, regional, and state governmental interests; elected officials and citizens; and private interests. Florida Department of Environmental Protection Noah Valenstein, Secretary Table A-1. Silver Springs and Upper Silver River and Rainbow Spring Group and Rainbow River stakeholders Type of Entity Name Agricultural Producers Marion County Alachua County Lake County Sumter County Levy County Putnam County City of Ocala City of Dunnellon City of Belleview Responsible Stakeholders The Villages On Top of the World Town of McIntosh City of Williston Town of Bronson City of Micanopy City of Hawthorne Town of Lady Lake City of Fruitland Park Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services Florida Department of Environmental Protection, including Silver Springs State Park and Rainbow Springs State Park, Oklawaha River Aquatic Preserve, and Rainbow Springs Aquatic Preserve Florida Department of Health Florida Department of Health in Marion County Responsible Agencies Florida Department of Health in Alachua County Florida Department of Health in Levy County Florida Department of Transportation District 2 Florida Department of Transportation District 5 St. -

Mounted on a Pedestal: Bertha Honoré Palmer Hope L

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 11-8-2007 Mounted on a Pedestal: Bertha Honoré Palmer Hope L. Black University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Black, Hope L., "Mounted on a Pedestal: Bertha Honoré Palmer" (2007). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/637 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mounted on a Pedestal: Bertha Honoré Palmer by Hope L. Black A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Liberal Arts Department of Humanities College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida CoMajor Professor: Gary Mormino, Ph.D. CoMajor Professor: Raymond Arsenault, Ph.D. Julie Armstrong, Ph.D. Date of Approval: November 8, 2007 Keywords: World’s Columbian Exposition, Meadowsweet Pastures, Great Chicago Fire, Manatee County, Seaboard Air Line Railroad © Copyright 2007, Hope L. Black Acknowledgements With my heartfelt appreciation to Professors Gary Mormino and Raymond Arsenault who allowed me to embark on this journey and encouraged and supported me on every path; to Greta ScheidWells who has been my lifeline; to Professors Julie Armstrong, Christopher Meindl, and Daryl Paulson, who enlightened and inspired me; to Ann Shank, Mark Smith, Dan Hughes, Lorrie Muldowney and David Baber of the Sarasota County History Center who always took the time to help me; to the late Rollins E. -

Fort King National Historic Landmark Education Guide 1 Fig5

Ai-'; ~,,111m11l111nO FORTKINO NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK Fig1 EDUCATION GUIDE This guide was made possible by the City of Ocala Florida and the Florida Department of State/Division of Historic Resources WELCOME TO Micanopy WE ARE EXCITED THAT YOU HAVE CHOSEN Fort King National Historic Fig2 Landmark as an education destination to shed light on the importance of this site and its place within the Seminole War. This Education Guide will give you some tools to further educate before and after your visit to the park. The guide gives an overview of the history associated with Fort King, provides comprehension questions, and delivers activities to Gen. Thomas Jesup incorporate into the classroom. We hope that this resource will further Fig3 enrich your educational experience. To make your experience more enjoyable we have included a list of items: • Check in with our Park Staff prior to your scheduled visit to confrm your arrival time and participation numbers. • The experience at Fort King includes outside activities. Please remember the following: » Prior to coming make staff aware of any mobility issues or special needs that your group may have. » Be prepared for the elements. Sunscreen, rain gear, insect repellent and water are recommended. » Wear appropriate footwear. Flip fops or open toed shoes are not recommended. » Please bring lunch or snacks if you would like to picnic at the park before or after your visit. • Be respectful of our park staff, volunteers, and other visitors by being on time. Abraham • Visitors will be exposed to different cultures and subject matter Fig4 that may be diffcult at times. -

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013

The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 COUNCIL ON LIBRARY AND INFORMATION RESOURCES AND THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929 by David Pierce September 2013 Mr. Pierce has also created a da tabase of location information on the archival film holdings identified in the course of his research. See www.loc.gov/film. Commissioned for and sponsored by the National Film Preservation Board Council on Library and Information Resources and The Library of Congress Washington, D.C. The National Film Preservation Board The National Film Preservation Board was established at the Library of Congress by the National Film Preservation Act of 1988, and most recently reauthorized by the U.S. Congress in 2008. Among the provisions of the law is a mandate to “undertake studies and investigations of film preservation activities as needed, including the efficacy of new technologies, and recommend solutions to- im prove these practices.” More information about the National Film Preservation Board can be found at http://www.loc.gov/film/. ISBN 978-1-932326-39-0 CLIR Publication No. 158 Copublished by: Council on Library and Information Resources The Library of Congress 1707 L Street NW, Suite 650 and 101 Independence Avenue, SE Washington, DC 20036 Washington, DC 20540 Web site at http://www.clir.org Web site at http://www.loc.gov Additional copies are available for $30 each. Orders may be placed through CLIR’s Web site. This publication is also available online at no charge at http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub158. -

Economic Importance and Public Preferences for Water Resource Management of the Ocklawaha River

Economic Importance and Public Preferences for Water Resource Management of the Ocklawaha River Tatiana Borisova ([email protected] ), Xiang Bi ([email protected]), Alan Hodges ([email protected]) Food and Resource Economics Department, and Stephen Holland ([email protected] ) Department of Tourism, Recreation, and Sport Management, University of Florida November 11, 2017 Photo of the Ocklawaha River near Eureka West Landing; March 2017 (credit: Tatiana Borisova) Ocklawaha River: Economic Importance and Public Preferences for Water Resource Management Tatiana Borisova ([email protected] ), Xiang Bi ([email protected]), Alan Hodges ([email protected]) Food and Resource Economics Department, Stephen Holland ([email protected] ) Department of Tourism, Recreation, and Sport Management, University of Florida Acknowledgements: Funding for this project was provided by the following organizations: Silver Springs Alliance, Florida Defenders of the Environment, Putnam County Environmental Council, Suwannee-St. Johns Sierra Club, Marion County Soil and Water Conservation District, St. Johns Riverkeeper, Sierra Club Foundation, and Felburn Foundation. We appreciate vehicle counter data for several locations in the study area shared by the Office of Greenways and Trails (Florida Department of Environmental Protection) and Marion County Parks and Recreation. The Florida Survey Research Center at the University of Florida designed the visitor interview questionnaire, and conducted the survey interviews with visitors. Finally, we are grateful to all -

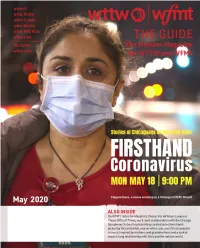

Wwciguide May 2020.Pdf

From the President & CEO The Guide The Member Magazine Dear Member, for WTTW and WFMT Thank you for your viewership, listenership, and continued support of WTTW and Renée Crown Public Media Center 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue WFMT. Now more than ever, we believe it is vital that you can turn to us for trusted Chicago, Illinois 60625 news and information, and high quality educational and entertaining programming whenever and wherever you want it. We have developed our May schedule with this Main Switchboard in mind. (773) 583-5000 Member and Viewer Services On WTTW, explore the personal, firsthand perspectives of people whose lives (773) 509-1111 x 6 have been upended by COVID-19 in Chicago in FIRSTHAND: Coronavirus. This new series of stories produced and released on wttw.com and our social media channels Websites wttw.com has been packaged into a one-hour special for television that will premiere on wfmt.com May 18 at 9:00 pm. Also, settle in for the new two-night special Asian Americans to commemorate Asian Pacific American Heritage Month. As America becomes more Publisher diverse, and more divided while facing unimaginable challenges, this film focuses a Anne Gleason Art Director new lens on U.S. history and the ongoing role that Asian Americans have played. On Tom Peth wttw.com, discover and learn about Chicago’s Japanese Culture Center established WTTW Contributors Julia Maish in 1977 in Chicago by Aikido Shihan (Teacher of Teachers) and Zen Master Fumio Lisa Tipton Toyoda to make the crafts, philosophical riches, and martial arts of Japan available WFMT Contributors to Chicagoans.