Inventing the Lady Manager: Rhetorically Constructing the “Working-Woman”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mounted on a Pedestal: Bertha Honoré Palmer Hope L

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 11-8-2007 Mounted on a Pedestal: Bertha Honoré Palmer Hope L. Black University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Black, Hope L., "Mounted on a Pedestal: Bertha Honoré Palmer" (2007). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/637 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mounted on a Pedestal: Bertha Honoré Palmer by Hope L. Black A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Liberal Arts Department of Humanities College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida CoMajor Professor: Gary Mormino, Ph.D. CoMajor Professor: Raymond Arsenault, Ph.D. Julie Armstrong, Ph.D. Date of Approval: November 8, 2007 Keywords: World’s Columbian Exposition, Meadowsweet Pastures, Great Chicago Fire, Manatee County, Seaboard Air Line Railroad © Copyright 2007, Hope L. Black Acknowledgements With my heartfelt appreciation to Professors Gary Mormino and Raymond Arsenault who allowed me to embark on this journey and encouraged and supported me on every path; to Greta ScheidWells who has been my lifeline; to Professors Julie Armstrong, Christopher Meindl, and Daryl Paulson, who enlightened and inspired me; to Ann Shank, Mark Smith, Dan Hughes, Lorrie Muldowney and David Baber of the Sarasota County History Center who always took the time to help me; to the late Rollins E. -

Dauntless Women in Childhood Education, 1856-1931. INSTITUTION Association for Childhood Education International, Washington,/ D.C

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 094 892 PS 007 449 AUTHOR Snyder, Agnes TITLE Dauntless Women in Childhood Education, 1856-1931. INSTITUTION Association for Childhood Education International, Washington,/ D.C. PUB DATE [72] NOTE 421p. AVAILABLE FROM Association for Childhood Education International, 3615 Wisconsin Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20016 ($9.50, paper) EDRS PRICE NF -$0.75 HC Not Available from EDRS. PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Biographical Inventories; *Early Childhood Education; *Educational Change; Educational Development; *Educational History; *Educational Philosophy; *Females; Leadership; Preschool Curriculum; Women Teachers IDENTIFIERS Association for Childhood Education International; *Froebel (Friendrich) ABSTRACT The lives and contributions of nine women educators, all early founders or leaders of the International Kindergarten Union (IKU) or the National Council of Primary Education (NCPE), are profiled in this book. Their biographical sketches are presented in two sections. The Froebelian influences are discussed in Part 1 which includes the chapters on Margarethe Schurz, Elizabeth Palmer Peabody, Susan E. Blow, Kate Douglas Wiggins and Elizabeth Harrison. Alice Temple, Patty Smith Hill, Ella Victoria Dobbs, and Lucy Gage are- found in the second part which emphasizes "Changes and Challenges." A concise background of education history describing the movements and influences preceding and involving these leaders is presented in a single chapter before each section. A final chapter summarizes the main contribution of each of the women and also elaborates more fully on such topics as IKU cooperation with other organizations, international aspects of IKU, the writings of its leaders, the standardization of curriculuis through testing, training teachers for a progressive program, and the merger of IKU and NCPE into the Association for Childhood Education.(SDH) r\J CS` 4-CO CI. -

Wwciguide May 2020.Pdf

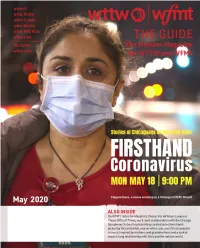

From the President & CEO The Guide The Member Magazine Dear Member, for WTTW and WFMT Thank you for your viewership, listenership, and continued support of WTTW and Renée Crown Public Media Center 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue WFMT. Now more than ever, we believe it is vital that you can turn to us for trusted Chicago, Illinois 60625 news and information, and high quality educational and entertaining programming whenever and wherever you want it. We have developed our May schedule with this Main Switchboard in mind. (773) 583-5000 Member and Viewer Services On WTTW, explore the personal, firsthand perspectives of people whose lives (773) 509-1111 x 6 have been upended by COVID-19 in Chicago in FIRSTHAND: Coronavirus. This new series of stories produced and released on wttw.com and our social media channels Websites wttw.com has been packaged into a one-hour special for television that will premiere on wfmt.com May 18 at 9:00 pm. Also, settle in for the new two-night special Asian Americans to commemorate Asian Pacific American Heritage Month. As America becomes more Publisher diverse, and more divided while facing unimaginable challenges, this film focuses a Anne Gleason Art Director new lens on U.S. history and the ongoing role that Asian Americans have played. On Tom Peth wttw.com, discover and learn about Chicago’s Japanese Culture Center established WTTW Contributors Julia Maish in 1977 in Chicago by Aikido Shihan (Teacher of Teachers) and Zen Master Fumio Lisa Tipton Toyoda to make the crafts, philosophical riches, and martial arts of Japan available WFMT Contributors to Chicagoans. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

SILVER SPRINGS: THE FLORIDA INTERIOR IN THE AMERICAN IMAGINATION By THOMAS R. BERSON A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Thomas R. Berson 2 To Mom and Dad Now you can finally tell everyone that your son is a doctor. 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my entire committee for their thoughtful comments, critiques, and overall consideration. The chair, Dr. Jack E. Davis, has earned my unending gratitude both for his patience and for putting me—and keeping me—on track toward a final product of which I can be proud. Many members of the faculty of the Department of History were very supportive throughout my time at the University of Florida. Also, this would have been a far less rewarding experience were it not for many of my colleagues and classmates in the graduate program. I also am indebted to the outstanding administrative staff of the Department of History for their tireless efforts in keeping me enrolled and on track. I thank all involved for the opportunity and for the ongoing support. The Ray and Mitchum families, the Cheatoms, Jim Buckner, David Cook, and Tim Hollis all graciously gave of their time and hospitality to help me with this work, as did the DeBary family at the Marion County Museum of History and Scott Mitchell at the Silver River Museum and Environmental Center. David Breslauer has my gratitude for providing a copy of his book. -

French Impressionist and Post Impressionist Paintings from the Collections of Mrs. Bertha Palmer Thorne and Mr. Gordon Palmer

FRENCH IMPRESSIONIST AND POST IMPRESSIONIST PAINTINGS from the Collections of MRS. BERTHA PALMER THORHE AND MR. GORDOH PALMER CATALOGUE WALKER ART MUSEUM Bowdoin College Bninf^wick, Maine May 11 ' June 17, 1962 Mrs. Bertha Palmer Thorne and Gordon Palmer are grandchildren of Mrs. Potter Palmer of Chicago who, in 1889, was one of the first Americans to introduce French Impressionst Painting to this country. While the greatest portion of Mrs. Palmer's collection is in the Art Institute of Chicago, many of the pictures in this exhibition were among those acquired by her. To this original group, our lenders have since added several important examples ranging in time and taste from Bou' din's La Plage to Picasso's Two Pigeons. It is a privilege for the Walker Art Museum of Bowdoin College to be able to present to a new audience such a distinguished group of pictures, many of which were the first of their kind to reach our shores. M. S. S. Lent by Mrs. Bertha Palmer Thorne Jean'Antoine Houdon (1714-1828), Portrait of a Little Girl, bronze sculpture Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot (1796' 1875), Trois Jeunes Filles pres d'un Arbre, oil Eugene Boudin (1824-1898), La Plage, oil Edouard Manet (1832-1883), Portrait of Berthe Morisot, lithograph Hilaire Germaine Edgar Degas (1834-1917), Mile. Wol\ons\a, etching Degas, Interior with Dancers^ monotype Henri Fantin-Latour (1836-1904), Women Embroidering^ lithograph Alfred Sisley (1839-1899), Landscape, oil Paul Cezanne (1839-1906), The Indwell, watercolor Cezanne, The ^uarrv, watercolor Cezanne, Mont St. -

Art Hand-Book, Sculpture, Architecture, Painting

:. •'t-o^ * ^^' v^^ ^ ^^^^\ ^^.m <. .*^ .. X 0° 0^ \D^ *'ir.s^ A < V ^^; .HO^ 4 o *^,'^:^'*.^*'^ "<v*-^-%o-' 'V^^''\/^ V*^^'%^ V\^ o '^^ o'/vT^^^ll^"" vy:. -rb^ ^oVv^'' '^J^M^^r^^ ^^jl.^0'rSi' ^oK °<<. ^""^^ • Sculpture » Architecture * Painting Official H^NDBOOKo/ARCHITECTVRE and SCULPTURE and ART CATALOGUE TO THE Pan-American Exposition With Maps and Illustrations by -permission of C. D. Arnold, Official Photographer BUFFALO, NEW YORK, U. S. A., MAT FIRST TO NOVEMBER FIRST, M. CM. & I. Published by DAVID GRAY, Buffalo, N. Y. Entered according to Act of Congress in the year 1901, by David Gray, in the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C. • • • • • e • • •• V. • » » « » . f>t • •_••» »'t»» » » » * • • . CONGRESS, Two Copiea Received JUN. 17 1901 Copyright entry EXPOSITION, 1901. CLASS ^XXc N». PAN-AMERICAN Buffalo, N. Y. , U. S. A COPY 3, Office of Director-General. March 30, 1901. To whom it may concern: — Mr. David Gray of this City has "been granted hy the Exposition a concession to publish the Art Catalogue of the Exposition^ which will he a hook in reality a memorial of the ideals of the Exposition in Archi- tecture, Sculpture and Pine Arts. WILLIAM I. BUCHANAN, Director-General The articles, pictures and catalogue descriptions in the Pan-American Art Hand Book are copyrighted, and publication thereof without permission is forbidden. \ r..k^ ^'««- -^ -"^^ ^^ This Art Hand Book was made by the publishing and printing house of ISAAC H,. BLANCHARD CO,, in the city of New Torky at 268 and 270 Canal Street, * 200 feet, iij9 inches east of Broadway. -

The Woman's Building of the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893

The Invisible Triumph: The Woman's Building of the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893 JAMES V. STRUEBER Ohio State University, AT1 JOHANNA HAYS Auburn University INTRODUCTION from Engineering Magazine, The World's Columbian Exposition (WCE) was the first world exposition outside of Europe and was to Thus has Chicago gloriously redeemed the commemorate the four hundredth anniversary of obligations incurred when she assumed the Columbus reaching the New World. The exhibition's task of building a World's Fair. Chicago's planners aimed at exceeding the fame of the 1889 businessmen started out to prepare for a Paris World Exposition in physical size, scope of finer, bigger, and more successful enter- accomplishment, attendance, and profitability.' prise than the world had ever seen in this With 27 million attending equaling approximately line. The verdict of the jury of the nations 40% of the 1893 US population, they exceeded of the earth, who have seen it, is that it the Paris Exposition in all accounts. This was partly is unquestionably bigger and undoubtedly accomplished by being open on Sundays-a much finer, and now it is assuredly more success- debated moral issue-the attraction of the newly ful. Great is Chicago, and we are prouder invented Ferris wheel, cheap quick nationwide than ever of her."5 transportation provided by the new transcontinental railroad system all helped to make a very successful BACKGROUND financial plans2Surprisingly, the women's contribu- tion to the exposition, which included the Woman's Labeled the "White City" almost immediately, for Building and other women's exhibits accounted for the arrangement of the all-white neo-Classical and 57% of total exhibits at the exp~sition.~In addition neo-High Renaissance architectural style buildings railroad development to accommodate the exposi- around a grand court and fountain poolI6 the WCE tion, set the heart of American trail transportation holds an ironic position in American history. -

Enid Yandell

H-Kentucky Enid Yandell Archive Item published by Randolph Hollingsworth on Tuesday, November 12, 2019 Project Name: Kentucky Woman Suffrage Name of Historic Site: Cave Hill Cemetery Event(s)/Use associated with woman/group/site: Burial site of sculptor Enid Bland Yandell (1896-1934) who supported the woman suffrage movement County: Jefferson Town/City: Louisville Zip Code: 40204 Street Address: 701 Baxter Avenue Associated Organization: Cave Hill Cemetery Years of Importance: 1912-1920 Geographic Location: Citation: Randolph Hollingsworth. Enid Yandell. H-Kentucky. 11-12-2019. https://networks.h-net.org/enid-yandell Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. 1 H-Kentucky Your Affiliation: Kentucky Woman Suffrage Project Additional Comments: The sculptor Enid Bland Yandell (6 October 1869 – 12 or 13 June 1934) was a strong advocate for women's rights. Born in Louisville, Kentucky, Yandell traveled extensively and was one of the first women to join the National Sculpture Society. She set up her first artist's studio in her parents' home on Broadway (between 3rd & 4th Street) in Louisville as early as 1891. She lived for two years in Chicago while working in the artist community working on the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition, then she moved to New York City and lived at 23 East 75th Street with her studio located at . She often traveled to Paris and lived there from 1895-1903 while living with the Hungarian expatriate Baroness Geysa Hortense de Braunecker (1869-1960). She had a studio in the Impasse du Main while living in Paris. -

Historic Properties Identification Report

Section 106 Historic Properties Identification Report North Lake Shore Drive Phase I Study E. Grand Avenue to W. Hollywood Avenue Job No. P-88-004-07 MFT Section No. 07-B6151-00-PV Cook County, Illinois Prepared For: Illinois Department of Transportation Chicago Department of Transportation Prepared By: Quigg Engineering, Inc. Julia S. Bachrach Jean A. Follett Lisa Napoles Elizabeth A. Patterson Adam G. Rubin Christine Whims Matthew M. Wicklund Civiltech Engineering, Inc. Jennifer Hyman March 2021 North Lake Shore Drive Phase I Study Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... v 1.0 Introduction and Description of Undertaking .............................................................................. 1 1.1 Project Overview ........................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 NLSD Area of Potential Effects (NLSD APE) ................................................................................... 1 2.0 Historic Resource Survey Methodologies ..................................................................................... 3 2.1 Lincoln Park and the National Register of Historic Places ............................................................ 3 2.2 Historic Properties in APE Contiguous to Lincoln Park/NLSD ....................................................... 4 3.0 Historic Context Statements ........................................................................................................ -

Women and Arts : 75 Quotes

WOMEN AND ARTS : 75 QUOTES Compiled by Antoni Gelonch-Viladegut For the Gelonch Viladegut Collection website Paris, March 2011 1 SOMMARY A GLOBAL INTRODUCTION 3 A SHORT HISTORY OF WOMEN’S ARTISTS 5 1. The Ancient and Classic periods 5 2. The Medieval Era 6 3. The Renaissance era 7 4. The Baroque era 9 5. The 18th Century 10 6. The 19th Century 12 7. The 20th Century 14 8. Contemporary artists 17 A GENERAL BIBLIOGRAPHY 19 75 QUOTES: WOMEN AND THE ART 21 ( chronological order) THE QUOTES ORDERED BY TOPICS 30 Art’s Definition 31 The Artist and the artist’s work 34 The work of art and the creation process 35 Function and art’s understanding 37 Art and life 39 Adjectives’ art 41 2 A GLOBAL INTRODUCTION In the professional world we often speak about the "glass ceiling" to indicate a situation of not-representation or under-representation of women regarding the general standards presence in posts or roles of responsibility in the profession. This situation is even more marked in the world of the art generally and in the world of the artists in particular. In the art history women’s are not almost present and in the world of the art’s historians no more. With this panorama, the historian of the art Linda Nochlin, in 1971 published an article, in the magazine “Artnews”, releasing the question: "Why are not there great women artists?" Nochlin throws rejects first of all the presupposition of an absence or a quasi-absence of the women in the art history because of a defect of " artistic genius ", but is not either partisan of the feminist position of an invisibility of the women in the works of art history provoked by a sexist way of the discipline. -

3122298.PDF (5.565Mb)

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE ANTIMODERN STRATEGIES: AMBIVALENCE, ACCOMMODATION, AND PROTEST IN WILLA CATHER’S THE TROLL GARDEN A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By STEPHANIE STRINGER GROSS Norman, Oklahoma 2004 UMI Number: 3122298 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI UMI Microform 3122298 Copyright 2004 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ©Copyright by STEPHANIE STRINGER GROSS 2004 All Rights Reserved. ANTIMODERN STRATEGIES: AMBIVALENCE, ACCOMMODATION, AND PROTEST IN WILLA CATHER’S THE TROLL GARDEN A Dissertation APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH Dr. Ronald Schleifer, Director Dr. William HenrYiMcDonald )r. Francesca Savraya Dr. Melissa/I. Homestead Dr. Robert Griswold ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project would never have been completed without the many hours of discussions with members of my committee, Professors Henry McDonald, Melissa Homestead, Francesca Sawaya, and Robert Griswold, and especially Professor Ronald Schleifer, and their patience with various interminable drafts. -

Cultural Resource Assessment Survey Lakewood Ranch Boulevard Extension Sarasota County, Florida

CULTURAL RESOURCE ASSESSMENT SURVEY LAKEWOOD RANCH BOULEVARD EXTENSION SARASOTA COUNTY, FLORIDA Performed for: Kimley-Horn 1777 Main Street, Suite 200 Sarasota, Florida 34326 Prepared by: Florida’s First Choice in Cultural Resource Management Archaeological Consultants, Inc. 8110 Blaikie Court, Suite A Sarasota, Florida 34240 (941) 379-6206 Toll Free: 1-800-735-9906 June 2016 CULTURAL RESOURCE ASSESSMENT SURVEY LAKEWOOD RANCH BOULEVARD EXTENSION SARASOTA COUNTY, FLORIDA Performed for: Kimley-Horn 1777 Main Street, Suite 200 Sarasota, Florida 34326 By: Archaeological Consultants, Inc. 8110 Blaikie Court, Suite A Sarasota, Florida 34240 Marion M. Almy - Project Manager Lee Hutchinson - Project Archaeologist Katie Baar - Archaeologist Thomas Wilson - Architectural Historian June 2016 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A cultural resource assessment survey (CRAS) of the Lakewood Ranch Boulevard Extension, in Sarasota, Florida, was performed by Archaeological Consultants, Inc (ACI). The purpose of this survey was to locate and identify any cultural resources within the project area and to assess their significance in terms of eligibility for listing in the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) and the Sarasota County Register of Historic Places (SCRHP). This report is in compliance with the Historic Preservation Chapter of Apoxsee and Article III, Chapter 66 (Sub-Section 66-73) of the Sarasota County Code, as well as with Chapters 267 and 373, Florida Statutes (FS), Florida’s Coastal Management Program, and implementing state regulations regarding possible impact to significant historical properties. The report also meets specifications set forth in Chapter 1A-46, Florida Administrative Code (FAC) (revised August 21, 2002). Background research, including a review of the Florida Master Site File (FMSF), and the NRHP indicated no prehistoric archaeological sites were recorded in the project area.