Palmer House Hotel 17 E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pittsfield Building 55 E

LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT Pittsfield Building 55 E. Washington Preliminary Landmarkrecommendation approved by the Commission on Chicago Landmarks, December 12, 2001 CITY OFCHICAGO Richard M. Daley, Mayor Departmentof Planning and Developement Alicia Mazur Berg, Commissioner Cover: On the right, the Pittsfield Building, as seen from Michigan Avenue, looking west. The Pittsfield Building's trademark is its interior lobbies and atrium, seen in the upper and lower left. In the center, an advertisement announcing the building's construction and leasing, c. 1927. Above: The Pittsfield Building, located at 55 E. Washington Street, is a 38-story steel-frame skyscraper with a rectangular 21-story base that covers the entire building lot-approximately 162 feet on Washington Street and 120 feet on Wabash Avenue. The Commission on Chicago Landmarks, whose nine members are appointed by the Mayor, was established in 1968 by city ordinance. It is responsible for recommending to the City Council that individual buildings, sites, objects, or entire districts be designated as Chicago Landmarks, which protects them by law. The Comm ission is staffed by the Chicago Department of Planning and Development, 33 N. LaSalle St., Room 1600, Chicago, IL 60602; (312-744-3200) phone; (312 744-2958) TTY; (312-744-9 140) fax; web site, http ://www.cityofchicago.org/ landmarks. This Preliminary Summary ofInformation is subject to possible revision and amendment during the designation proceedings. Only language contained within the designation ordinance adopted by the City Council should be regarded as final. PRELIMINARY SUMMARY OF INFORMATION SUBMITIED TO THE COMMISSION ON CHICAGO LANDMARKS IN DECEMBER 2001 PITTSFIELD BUILDING 55 E. -

333 North Michigan Buildi·N·G- 333 N

PRELIMINARY STAFF SUfv1MARY OF INFORMATION 333 North Michigan Buildi·n·g- 333 N. Michigan Avenue Submitted to the Conwnission on Chicago Landmarks in June 1986. Rec:ornmended to the City Council on April I, 1987. CITY OF CHICAGO Richard M. Daley, Mayor Department of Planning and Development J.F. Boyle, Jr., Commissioner 333 NORTH MICIDGAN BUILDING 333 N. Michigan Ave. (1928; Holabird & Roche/Holabird & Root) The 333 NORTH MICHIGAN BUILDING is one of the city's most outstanding Art Deco-style skyscrapers. It is one of four buildings surrounding the Michigan A venue Bridge that defines one of the city' s-and nation' s-finest urban spaces. The building's base is sheathed in polished granite, in shades of black and purple. Its upper stories, which are set back in dramatic fashion to correspond to the city's 1923 zoning ordinance, are clad in buff-colored limestone and dark terra cotta. The building's prominence is heightened by its unique site. Due to the jog of Michigan Avenue at the bridge, the building is visible the length of North Michigan Avenue, appearing to be located in the center of the street. ABOVE: The 333 North Michigan Building was one of the first skyscrapers to take advantage of the city's 1923 zoning ordinance, which encouraged the construction of buildings with setback towers. This photograph was taken from the cupola of the London Guarantee Building. COVER: A 1933 illustration, looking south on Michigan Avenue. At left: the 333 North Michigan Building; at right the Wrigley Building. 333 NORTH MICHIGAN BUILDING 333 North Michigan Avenue Architect: Holabird and Roche/Holabird and Root Date of Construction: 1928 0e- ~ 1QQ 2 00 Cft T Dramatically sited where Michigan Avenue crosses the Chicago River are four build ings that collectively illustrate the profound stylistic changes that occurred in American architecture during the decade of the 1920s. -

Social Media and Popular Places: the Case of Chicago Kheir Al-Kodmany†

International Journal of High-Rise Buildings International Journal of June 2019, Vol 8, No 2, 125-136 High-Rise Buildings https://doi.org/10.21022/IJHRB.2019.8.2.125 www.ctbuh-korea.org/ijhrb/index.php Social Media and Popular Places: The Case of Chicago Kheir Al-Kodmany† Department of Urban Planning and Policy, University of Illinois at Chicago, USA Abstract This paper offers new ways to learn about popular places in the city. Using locational data from Social Media platforms platforms, including Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram, along with participatory field visits and combining insights from architecture and urban design literature, this study reveals popular socio-spatial clusters in the City of Chicago. Locational data of photographs were visualized by using Geographic Information Systems and helped in producing heat maps that showed the spatial distribution of posted photographs. Geo-intensity of photographs illustrated areas that are most popularly visited in the city. The study’s results indicate that the city’s skyscrapers along open spaces are major elements of image formation. Findings also elucidate that Social Media plays an important role in promoting places; and thereby, sustaining a greater interest and stream of visitors. Consequently, planners should tap into public’s digital engagement in city places to improve tourism and economy. Keywords: Social media, Iconic socio-spatial clusters, Popular places, Skyscrapers 1. Introduction 1.1. Sustainability: A Theoretical Framework The concept of sustainability continues to be of para- mount importance to our cities (Godschalk & Rouse, 2015). Planners, architects, economists, environmentalists, and politicians continue to use the term in their conver- sations and writings. -

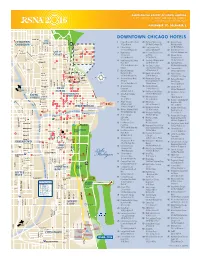

Hotel-Map.Pdf

RADIOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF NORTH AMERICA 102ND SCIENTIFIC ASSEMBLY AND ANNUAL MEETING McCORMICK PLACE, CHICAGO NOVEMBER 27 – DECEMBER 2 DOWNTOWN CHICAGO HOTELS OLD CLYBOURN 1 Palmer House Hilton Hotel 28 Fairmont Hotel Chicago 61 Monaco Chicago, CORRIDOR TOWN 17 East Monroe 200 North Columbus Dr. A Kimpton Hotel 2 Hilton Chicago 29 Four Seasons Hotel 225 North Wabash 23 720 South Michigan Ave. 120 East Delaware Pl. 62 Omni Chicago Hotel GOLD 60 70 3 Hyatt Regency 30 Freehand Chicago Hostel 676 North Michigan Ave. COAST 29 87 38 66 Chicago Hotel and Hotel 63 Palomar Chicago, 89 68 151 East Wacker Dr. 19 East Ohio St. A Kimpton Hotel 80 47 4 Hyatt Regency McCormick 31 The Gray, A Kimpton Hotel 505 North State St. Place Hotel 122 W. Monroe St. 64 Park Hyatt Hotel 2233 South Martin Luther 32 The Gwen, a Luxury 800 North Michigan Ave. King Dr. Collection Hotel, Chicago 65 Peninsula Hotel 5 Marriott Downtown 521 North Rush St. 108 East Superior St. 79 Magnificent Mile 33 Hampton Inn & Suites 66 Public Chicago 86 540 North Michigan Ave. 33 West Illinois St. 78 1301 North State Pkwy. Sheraton Chicago Hotel Hampton Inn Chicago 75 6 34 67 Radisson Blu Aqua & Towers Downtown Magnificent Mile 73 Hotel Chicago 301 East North Water St. 160 East Huron 221 N. Columbus Dr. 64 7 AC Hotel Chicago 35 Hampton Majestic 68 Raffaello Hotel NEAR 65 59 Downtown 22 West Monroe St. 201 East Delaware Pl. 62 10 34 42 630 North Rush St. NORTH 36 Hard Rock Hotel Chicago 69 Renaissance Chicago 46 21 MAGNIFICENT 230 North Michigan Ave. -

The True Mary Todd Lincoln ALSO by BETTY BOLES ELLISON

The True Mary Todd Lincoln ALSO BY BETTY BOLES ELLISON The Early Laps of Stock Car Racing: A History of the Sport and Business through 1974 (McFarland, 2014) The True Mary Todd Lincoln A Biography BETTY BOLES ELLISON McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Ellison, Betty Boles. The true Mary Todd Lincoln : a biography / Betty Boles Ellison. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7864-7836-1 (softcover : acid free paper) ♾ ISBN 978-1-4766-1517-2 (ebook) 1. Lincoln, Mary Todd, 1818–1882. 2. Presidents’ spouses—United States— Biography. 3. Lincoln, Abraham, 1809–1865—Family. I. Title. E457.25.L55E45 2014 973.7092—dc23 [B] 2014003651 BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE © 2014 Betty Boles Ellison. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. On the cover: Oil portrait of a twenty-year-old Mary Todd painted in 1928 by Katherine Helm, a niece of Mary Todd Lincoln and daughter of Confederate General Ben H. Helm. It is based on a daguerreotype taken in Springfield by N.H. Shepherd in 1846; a companion daguerreotype is the earliest known photograph of Lincoln (courtesy of the Abraham Lincoln Library and Museum of Lincoln Memorial University, Harrogate, Tennessee) Manufactured in the United States of America McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com For Sofia E. -

Streeterville Neighborhood Plan 2014 Update II August 18, 2014

Streeterville Neighborhood Plan 2014 update II August 18, 2014 Dear Friends, The Streeterville Neighborhood Plan (“SNP”) was originally written in 2005 as a community plan written by a Chicago community group, SOAR, the Streeterville Organization of Active Resi- dents. SOAR was incorporated on May 28, 1975. Throughout our history, the organization has been a strong voice for conserving the historic character of the area and for development that enables divergent interests to live in harmony. SOAR’s mission is “To work on behalf of the residents of Streeterville by preserving, promoting and enhancing the quality of life and community.” SOAR’s vision is to see Streeterville as a unique, vibrant, beautiful neighborhood. In the past decade, since the initial SNP, there has been significant development throughout the neighborhood. Streeterville’s population has grown by 50% along with new hotels, restaurants, entertainment and institutional buildings creating a mix of uses no other neighborhood enjoys. The balance of all these uses is key to keeping the quality of life the highest possible. Each com- ponent is important and none should dominate the others. The impetus to revising the SNP is the City of Chicago’s many new initiatives, ideas and plans that SOAR wanted to incorporate into our planning document. From “The Pedestrian Plan for the City”, to “Chicago Forward”, to “Make Way for People” to “The Redevelopment of Lake Shore Drive” along with others, the City has changed its thinking of the downtown urban envi- ronment. If we support and include many of these plans into our SNP we feel that there is great- er potential for accomplishing them together. -

Mounted on a Pedestal: Bertha Honoré Palmer Hope L

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 11-8-2007 Mounted on a Pedestal: Bertha Honoré Palmer Hope L. Black University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Black, Hope L., "Mounted on a Pedestal: Bertha Honoré Palmer" (2007). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/637 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mounted on a Pedestal: Bertha Honoré Palmer by Hope L. Black A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Liberal Arts Department of Humanities College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida CoMajor Professor: Gary Mormino, Ph.D. CoMajor Professor: Raymond Arsenault, Ph.D. Julie Armstrong, Ph.D. Date of Approval: November 8, 2007 Keywords: World’s Columbian Exposition, Meadowsweet Pastures, Great Chicago Fire, Manatee County, Seaboard Air Line Railroad © Copyright 2007, Hope L. Black Acknowledgements With my heartfelt appreciation to Professors Gary Mormino and Raymond Arsenault who allowed me to embark on this journey and encouraged and supported me on every path; to Greta ScheidWells who has been my lifeline; to Professors Julie Armstrong, Christopher Meindl, and Daryl Paulson, who enlightened and inspired me; to Ann Shank, Mark Smith, Dan Hughes, Lorrie Muldowney and David Baber of the Sarasota County History Center who always took the time to help me; to the late Rollins E. -

Iconic Chicago Loop Retail

ICONIC CHICAGO LOOP RETAIL Bank of America, Dunkin Donuts, AmeriCash Loans, Verizon W MADISON STREET 105 CHICAGO, ILLINOIS NET LEASE INVESTMENT OFFERING Table of Contents Bank of America, Dunkin Donuts, AmeriCash Loans, Verizon W MADISON STREET CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 105 - 1 - NET LEASE INVESTMENT OFFERING TABLE OF CONFIDENTIALITY & DISCLAIMER ................................. 3 CONTENTS: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................... 5 Investment Highlights Property Overview FINANCIAL OVERVIEW ......................................................... 9 Rent Roll Cash Flow Projections PROPERTY OVERVIEW .........................................................12 Photographs Aerials Site Plan & Traffic/Pedestrian Counts Maps MARKET & TENANT OVERVIEWS .....................................19 Demographic Comparison Report Tenant Profiles Location Overviews Surrounding Attractions CONTACT DETAILS ...............................................................30 Contact Information W MADISON STREET 105 CHICAGO, ILLINOIS - 2 - NET LEASE INVESTMENT OFFERING Disclaimer Statement Bank of America, Dunkin Donuts, AmeriCash Loans, Verizon W MADISON STREET CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 105 - 3 - NET LEASE INVESTMENT OFFERING DISCLAIMER The information contained in the following Offering Memorandum is proprietary and strictly confidential. It is intended to be reviewed only by the party receiving it from The Boulder STATEMENT: Group and should not be made available to any other person or entity without the written consent of The Boulder Group. -

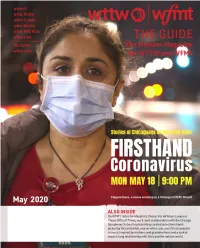

Wwciguide May 2020.Pdf

From the President & CEO The Guide The Member Magazine Dear Member, for WTTW and WFMT Thank you for your viewership, listenership, and continued support of WTTW and Renée Crown Public Media Center 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue WFMT. Now more than ever, we believe it is vital that you can turn to us for trusted Chicago, Illinois 60625 news and information, and high quality educational and entertaining programming whenever and wherever you want it. We have developed our May schedule with this Main Switchboard in mind. (773) 583-5000 Member and Viewer Services On WTTW, explore the personal, firsthand perspectives of people whose lives (773) 509-1111 x 6 have been upended by COVID-19 in Chicago in FIRSTHAND: Coronavirus. This new series of stories produced and released on wttw.com and our social media channels Websites wttw.com has been packaged into a one-hour special for television that will premiere on wfmt.com May 18 at 9:00 pm. Also, settle in for the new two-night special Asian Americans to commemorate Asian Pacific American Heritage Month. As America becomes more Publisher diverse, and more divided while facing unimaginable challenges, this film focuses a Anne Gleason Art Director new lens on U.S. history and the ongoing role that Asian Americans have played. On Tom Peth wttw.com, discover and learn about Chicago’s Japanese Culture Center established WTTW Contributors Julia Maish in 1977 in Chicago by Aikido Shihan (Teacher of Teachers) and Zen Master Fumio Lisa Tipton Toyoda to make the crafts, philosophical riches, and martial arts of Japan available WFMT Contributors to Chicagoans. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

SILVER SPRINGS: THE FLORIDA INTERIOR IN THE AMERICAN IMAGINATION By THOMAS R. BERSON A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2011 1 © 2011 Thomas R. Berson 2 To Mom and Dad Now you can finally tell everyone that your son is a doctor. 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my entire committee for their thoughtful comments, critiques, and overall consideration. The chair, Dr. Jack E. Davis, has earned my unending gratitude both for his patience and for putting me—and keeping me—on track toward a final product of which I can be proud. Many members of the faculty of the Department of History were very supportive throughout my time at the University of Florida. Also, this would have been a far less rewarding experience were it not for many of my colleagues and classmates in the graduate program. I also am indebted to the outstanding administrative staff of the Department of History for their tireless efforts in keeping me enrolled and on track. I thank all involved for the opportunity and for the ongoing support. The Ray and Mitchum families, the Cheatoms, Jim Buckner, David Cook, and Tim Hollis all graciously gave of their time and hospitality to help me with this work, as did the DeBary family at the Marion County Museum of History and Scott Mitchell at the Silver River Museum and Environmental Center. David Breslauer has my gratitude for providing a copy of his book. -

How Abraham Lincoln Became President

K- -jS"^-';^"- How Abraham Lincoln Became President ^niMTi By J. McCan Davis Centennial Edition 1809 - 1909 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY MEMORIAL the Class of 1901 founded by HARLAN HOYT HORNER and HENRIETTA CALHOUN HORNER MaauBMBmMM How Abraham Lincoln Became President Centennial Edition ">''-,*, «<:>;' ABRAHAM LINCOLN AS PRESIDENT. From an old steel engraving, after a photograph by Brady. How Abraham Lincoln Became President By J. McCAN DAVIS " " Author of The Breaking of the Deadlock," Abraham Lincoln His Book/* etc. Centennial Edition THE ILLINOIS COMPANY SPRINGFIELD. ILLINOIS 1909 Copyright, 1909 by J. McCan Davis Engravings made by the Capitol Engraving Company, Springfield, Illinois Press of the Henry O. Shepard Company '^1^ •^Z.^3 To the Soldiers of the Civil War, Comrades of My Father, the heroic men who offered their lives that '* government of the people, by the people, for the people shall not perish from the earth/* /M Cccu^^'^'CMXx-^ Foreword. Abraham Lincoln was in no sense an accident. His nomination for President in i860 surprised the country. Yet it was the logical result of a series of events that had extended over a period of many years. This was not wholly clear then, but it is plain enough now. It is the purpose of this little volume to tell briefly the story of his preparation for his colossal task and of the events that made him, almost inevitably, as it now seems. Chief Magistrate of the nation. There have been many great men in the world, and the future will bring forth more great men. But the world has produced only one Abraham Lincoln, and we may not expect another in all the generations yet unborn. -

Greektown Reektown Greektown Little Italy The

N Lakeview Ave W Fullerton Pkwy W Belden Ave N Lincoln t S ed A t v e W Webster Ave als N Lincoln Park West N Stockton Dr H N C N annon Dr W Dickens Ave N W Armitage Ave N C S t o c lar k t k S o n N L N Cleveland Ave t D t r ak S W Wisconsin St e S ed t hor als H N N Orchard St N Larrabee St e D r W Willow St W Eugenie St W North Ave North/Clybourn Sedgwick OLD TOWN CLYBOURN t Pkwy S e k r t a la CORRIDOR t N C N C N S N Dearborn Pkwy N Wells St lyb ourn A 32 ve W Division St Clark/ Division 1 Allerton Hotel (The) 24 E Elm St E Oak St Hyatt Regency McCormick Place GOLD 701 North Michigan Avenue 2233 South Martin Luther King t E Walton St 8 S COAST 2 Amalfi Hotel Chicago 25 ed 35 InterContinental Chicago t E Oak St 12 als John Hancock E Delaware Pl 45 16 20 West Kinzie Street 505 North Michigan Avenue H N Michigan Ave t t E Walton St S N Observatory S Dr t 44 E Delaware Pl 26 e S 3 t Chicago Marriott Downtown JW Marriott Chicago k alle E Chestnut St r a E Chestnut St S t la a Magnifi cent Mile 151 West Adams Street N L N Orleans N L N C N Dearborn Pwky N S 37 E Pearson St 540 North Michigan Avenue ak W Chicago Ave Chicago Chicago 30 27 e S Langham Chicago (The) t 4 hor Courtyard Chicago Downtown S W Superior St 28 31 e 330 North Wabash Avenue v O’Hare e D Magnifi cent Mile International W Huron St 1 165 East Ontario Street 28 Airport W Erie St r MileNorth, A Chicago Hotel N Franklin 20 21 43 W Ontario St 5 166 East Superior Street ichigan A Courtyard Chicago Downtown N M W Ohio St 4 7 ilw River North 29 22 N M Palmer House Hilton auk W Grand