State of the Art of Zuid-Holland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloaded from the Online Library of the International Society for Soil Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering (ISSMGE)

INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR SOIL MECHANICS AND GEOTECHNICAL ENGINEERING This paper was downloaded from the Online Library of the International Society for Soil Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering (ISSMGE). The library is available here: https://www.issmge.org/publications/online-library This is an open-access database that archives thousands of papers published under the Auspices of the ISSMGE and maintained by the Innovation and Development Committee of ISSMGE. Large diameter tunnelling under polders P.Autuori & S. Minec Bouygues Travaux Publics, Saint Quentin en Yvelines, France ABSTRACT: The latest underground works show how the tunnel boring machines can face more and more difficult conditions.An example of this trend is the Groene Hart tunnel, part of the High Speed Link dutch network, at present under construction by the Bouygues-Koop Consortium. This tunnel, with about 15 m diameter, was bored with the world largest confining tunnel boring machine (TBM) up to now. On the tunnel track, measuring more than 7 km, many requirements have to be fulfilled. In particular, in a soil extremely sensitive to the boring conditions, stringent settlement limitation (10 mm in some areas) are imposed because of the presence of buildings, roads, railways and utilities. Besides, the specific geotechnical conditions created by polders induce a very notable and quite uncommon phenomenon of increase of the natural pore pressure in soil (called Excess Pore Pressure or EPP) during boring which can affect tunnel cover stability. Therefore, detailed monitoring campaigns aimed at better understanding the hydraulic and mechanical soil behaviour have been carried out at different locations on the track. 1 INTRODUCTION circulation, both circulation tracks being separated by a central wall, including escape doors each 150 m. -

Rootsmagic Document

First Generation 1. Geert Somsen1 was born about 1666 in Aalten, GE, Netherlands. He died about 1730 in Aalten, GE, Netherlands. He has a reference number of [P272]. (Boeinck), ook wel: Sumps. Geert werd op 24-06-1686 (Sint Jan) ingeschreven als lidmaat van de Nederduits Gereformeerde Gemeente Aalten [Boeinck (also: Sumps). Geert was admitted as a member of the Dutch Reformed Church of Aalten on 24-06-1686 (St. John)]. Geert Somsen and Mechtelt Gelkinck had marriage banns published on 28 Apr 1689 in Aalten, GE, Netherlands. They were married on 27 May 1689 in Aalten, GE, Netherlands. Mechtelt Gelkinck1 (daughter of Roelof Somsen and Geesken Rensen) was born before 25 Aug 1662 in Aalten, GE, Netherlands. 2 She was christened on 25 Aug 1662 in Dinxperlo, GE, Netherlands.2 She died in Aalten, GE, Netherlands. She has a reference number of [P273]. ook wel: Meghtelt. Also: Sumps. op 29-09-1688 werd Mechtelt als lidmaat v.d. Nederduits Geref. Ge,. Aalten ingeschreven [also: Meghtelt. Also: Sumps. On 29 Sep 1688 she was registered as Mechtelt as a member of the Dutch Reformed Church in Aalten]. Geert Somsen and Mechtelt Gelkinck had the following children: +2 i. Jantjen Somsen (born on 9 Nov 1690). +3 ii. Roelof Somsen (born about 1692). +4 iii. Geesken Somsen (born in 1695). +5 iv. Wander Somsen (born on 9 Jul 1699). +6 v. Frerik Somsen (born about Jan 1703). Second Generation 2. Jantjen Somsen1 (Geert-1) was born on 9 Nov 1690 in Aalten, GE, Netherlands. She died on 15 Sep 1767 in Dinxperlo, GE, Netherlands. -

Planning the Horticultural Sector Managing Greenhouse Sprawl in the Netherlands

Planning the Horticultural Sector Managing Greenhouse Sprawl in the Netherlands Korthals Altes, W.K., Van Rij, E. (2013) Planning the horticultural sector: Managing greenhouse sprawl in the Netherlands, Land Use Policy, 31, 486-497 Abstract Greenhouses are a typical example of peri-urban land-use, a phenomenon that many planning systems find difficult to address as it mixes agricultural identity with urban appearance. Despite its urban appearance, greenhouse development often manages to evade urban containment policies. But a ban on greenhouse development might well result in under-utilisation of the economic value of the sector and its potential for sustainability. Specific knowledge of the urban and rural character of greenhouses is essential for the implementation of planning strategies. This paper analyses Dutch planning policies for greenhouses. It concludes with a discussion of how insights from greenhouse planning can be applied in other contexts involving peri-urban areas. Keywords: greenhouses; horticulture; land-use planning; the Netherlands; peri-urban land-use 1 Introduction The important role played by the urban-rural dichotomy in planning practice is a complicating factor in planning strategies for peri-urban areas, often conceptualised as border areas (the rural-urban fringe) or as an intermediate zone between city and countryside (the rural-urban transition zone) (Simon, 2008). However, “[t]he rural-urban fringe has a special, and not simply a transitional, land-use pattern that distinguishes it from more distant countryside and more urbanised space.” (Gallent and Shaw, 2007, 621) Planning policies tend to overlook this specific peri-environment, focusing rather on the black-and-white difference between urban and rural while disregarding developments in the shadow of cities (Hornis and Van Eck, 2008). -

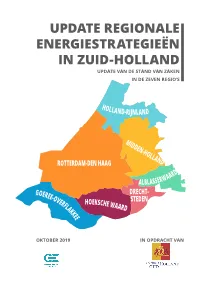

PZH Evaluatie Update RES Rapport

UPDATE REGIONALE IN DE ZEVEN REGIO’S UPDATE VAN DE STAND VAN ZAKEN ENERGIESTRATEGIEËNIN ZUID-HOLLANDD LAN RIJN ND- HOLLA MIDDEN-HOLLAND D R AA W ER SS LA ALB DRECHT- STEDEN ROTTERDAM-DEN HAAG RD E WAA KSCH HOE IN OPDRACHT VAN EREE-OVERFLAK GO KEE OKTOBER 2019 2 1| INLEIDING INLEIDING Dit document is een update van de studie ‘Regionale Energiestrategieeën in Zuid-Holland, analyse en vergelijking van de stand van zaken in de zeven regio’s’, uit augustus 2018. Deze update kijkt dus naar de huidige stand van zaken, in oktober 2019. De provincie Zuid-Holland bestaat uit 7 RES-regio’s; Alblasserwaard, Drechtsteden, Goeree-Overflakkee, Hoeksche Waard, Holland-Rijnland, Midden-Holland, en Rotterdam-Den Haag. Voor de dikgedrukte vier regio’s zijn nieuwe documenten aangeleverd die in de update gebruikt zijn: - Alblasserwaard: BVR-eindrapport (conceptversie) - Alblasserwaard: Res vervolgproces_alblasserwaard - Drechtsteden: transitievisie warmte 1.0 - Holland-Rijnland : Energieakkoord Holland Rijnland 2017-2025, Uitvoeringsprogramma 2019 - Holland-Rijnland: Notitie ‘Van Regionaal Energieakkoord Holland Rijnland naar Regionale Energiestrategie (RES) Holland Rijnland’ - Rotterdam-Den Haag: Energieperspectief 2050 Rotterdam-Den Haag - Rotterdam-Den Haag: Regionale prioriteiten RES De gebruikte bronnen van het rapport van augustus 2018 staan genoemd ‘Regionale Energiestrategieeën in Zuid-Holland, analyse en vergelijking van de stand van zaken in de zeven regio’s’, uit augustus 2018. In deze update is de nadruk gelegd op de regio Rotterdam-Den Haag, Alblasserwaard, Drechtsteden en Holland- Rijnland omdat er voor deze deelregio’s nieuwe documenten ontwikkeld zijn. Voor de overige regio’s zijn er in dit overzichtsdocument geen aanpassingen gedaan. Wel zijn de aangepaste grenzen van de deelregio’s en van de provincie aangepast naar 2019. -

Op Pad in Het

ONTDEK DE RUST EN DE RUIMTE OP PAD IN HET Met verrassende wandel, fiets- en vaarroutes Hollands landschap PROEF HET PLATTELAND Historie leeft WATER BETOVERT 02 #oppadinhetgroenehart 03 #oppadinhetgroenehart 4 Wandel en fietsroutes 8 Historie leeft 14 Proef het platteland 20 Iconen van het Groene Hart 22 Water betovert 28 Hollands Landschap In een prachtig, groen gebied tussen de 32 Aanbiedingen steden Amsterdam, Utrecht, Den Haag en 34 Meer informatie Rotterdam, ligt een oase van rust, ruimte en natuur: het Groene Hart. Je wandelt en fietst er door de polders en vaart over de Hollandse Plassen. Dit magazine is een bron van inspiratie voor iedereen die dit Ga op pad... oer- Hollandse, landelijke gebied beter wil en maak de mooiste foto's Waar je ook bent in het Groene Hart, je spot leren kennen. altijd wel iets moois om vast te leggen. Leuk als jij je foto's met ons wilt delen! Mail ze aan Het Groene Hart heeft een rijke geschiede- [email protected] en wij delen de mooiste nis, die je nog dagelijks ziet. Van de Oude op onze social media. Dan zien we je daar! Hollandse Waterlinie en de Romeinse Limes tot en met de molens van Werelderfgoed Kinderdijk. In oude vestingstadjes als Oudewater, Schoonhoven en Leerdam. Het Hollandse landschap is uniek. Met charmante streek met vier gemeenten: boerensloten, groene weides en bijna altijd Gouda, Woerden, Bodegraven-Reeuwijk en wel een molen aan de horizon. En dan het Krimpenerwaard. Hier zie je hoe kaas wordt water. Of je nu met een fluisterbootje de gemaakt en verhandeld. Maar waar je ook OP PAD IN HET adembenemende Nieuwkoopse of Reeu- komt, overal tref je leuke restaurants, cafés wijkse Plassen ontdekt of in de Vinkeveense en terrasjes, om van het leven te genieten. -

Bestemmingsplan Landelijk Gebied Voormalig Gemeente Nederlek

Bestemmingsplan Landelijk Gebied Voormalig gemeente Nederlek Gemeente Krimpenerwaard Afdeling Ruimtelijke Ontwikkeling IDN: NL.IMRO.1931.BP1509BG008-VG01 Status: defintief Versie: 01 Datum: 24 april 2018 Bestemmingsplan Landelijk Gebied (voormalige gemeente Nederlek) Toelichting Toelichting 1 Toelichting - Bestemmingsplan Landelijk Gebied (voormalige gemeente Nederlek) (NL.IMRO.1931.BP1507BG005-VG01) 2 Toelichting - Bestemmingsplan Landelijk Gebied (voormalige gemeente Nederlek) (NL.IMRO.1931.BP1507BG005-VG01) Inhoudsopgave 1. INLEIDING ....................................................................................................... 5 1.1 AANLEIDING ..................................................................................................... 5 1.2 PROBLEEM- EN DOELSTELLING ................................................................................. 5 1.3 DE BEGRENZING VAN HET PLANGEBIED ........................................................................ 6 1.4 TOTSTANDKOMING VAN DE HERZIENING ...................................................................... 8 1.5 OPBOUW BESTEMMINGSPLAN ................................................................................... 8 2. GEBIEDSBESCHRIJVING ................................................................................... 9 2.1 INLEIDING ....................................................................................................... 9 2.2 ONTSTAANSGESCHIEDENIS ..................................................................................... 9 2.3 -

Study of Downstream Migrating Salmon Smolt in the River Rhine Using the NEDAP Trail System: 2006 and Preliminary Results 2007

Not to be cited without permission of the author International Council for North Atlantic Salmon the Exploration of the Sea Working Group Working Paper 2007/26 Study of downstream migrating salmon smolt in the River Rhine using the NEDAP Trail System: 2006 and preliminary results 2007 by Detlev Ingendahl *, Gerhard Feldhaus *, Gerard de Laak, Tim Vriese and André Breukelaar. *Bezirksregierung Arnsberg, Fishery and Freshwater ecology, Heinsbergerstr. 53, 57399 Kirchhundem, Germany Sportvisserij Nederland, Visadvies, RIZA Running headline: Downstream migrating salmon smolt in the River Rhine Key words: Salmon smolt, downstream migration, River Rhine, Nedap Trail system, Delta Abstract Downstream migration of Atlantic salmon smolt was studied in the River Rhine in 2006 and 2007 using the NEDAP Trail system. In 2006 10 fish and in 2007 78 fish were released into two tributaries of the River Rhine (R. Sieg in 2006 and R. Wupper in 2007). The smolts (> 150 g) were tagged with a transponder (length 3.5 cm, weight 11.5 g) by surgery and introduction into the body cavity. After a recovery period of three days (2006) and ten days (2007), respectively in the hatchery the fish were released into the river. The transponder equipped fish can be detected by fixed antenna stations when leaving the tributary and during their migration through the Rhine delta to the sea. The NEDAP trail system is based on inductive coupling between an antenna loop at the river bottom and the ferrite rod antenna within the transponders. Each transponder gives its unique ID- number when the fish is passing a detection station. Until now 64 fish left the river of release (5 in 2006 and 59 in 2007, respectively). -

Rapportage Onderhoudsplan

Rapportage Onderhoudsplan Gemeente Bodegraven-Reeuwijk Rapportage Onderhoudsplan Definitief Datum: 25 maart 2021 Gemeente Projectnummer: 18015 Bodegraven-Reeuwijk Auteurs: Hannemarie Hardeman, Senior onderzoeker Roanne van de Wijgaart, Onderzoeker Moventem BV T 0575 84 3738 E [email protected] W www.moventem.nl Moventem werkt conform de Gedragscode voor Onderzoek & Statistiek van de Nederlandse Marktonderzoek Associatie (MOA) en mag het Fair Data Keurmerk voeren, waarmee wordt aangetoond dat op verantwoorde wijze met data en persoonsgegevens wordt omgaan. Tevens is Moventem aangesloten bij de Europese Vereniging voor Marktonderzoek (ESOMAR) en wordt voldaan aan de Internationale Code voor Markt- en sociaalwetenschappelijk onderzoek. Dit rapport is met grote zorg samengesteld. Desondanks kan het voorkomen dat informatie fout en/of onvolledig is. Moventem is niet aansprakelijk voor enige directe of indirecte schade die zou kunnen ontstaan door het gebruik van de aangeboden informatie. 2 Gemeente Inhoudsopgave Bodegraven-Reeuwijk Management Samenvatting Pagina 4 1 Inleiding Pagina 8 1.1 Onderzoeksopzet Pagina 9 2 Resultaten Pagina 10 2.1 Bekendheid met onderhoudsplan Pagina 11 2.2 Verbeteringen openbare ruimte Pagina 12 2.3 Communicatie rond herinrichtingswerkzaamheden Pagina 52 2.4 Communicatie rond meldingen openbare ruimte Pagina 56 2.5 Samen verantwoordelijk voor openbare ruimte Pagina 61 2.6 Klimaatadaptatie Pagina 66 2.7 Natuurlijk groenbeheer Pagina 76 3 Bijlagen Pagina 79 Bijlage l Achtergrondvariabelen Pagina 80 Bijlage ll Onderzoeksverantwoording Pagina 81 3 Management Samenvatting 4 Gemeente Management samenvatting Bodegraven-Reeuwijk Bekendheid met onderhoudsplan Aan de respondenten is gevraagd of zij het huidige onderhoudsplan voor de leefomgeving voor de periode 2018-2021 kennen. 18% kent deze (enigszins). 38% heeft er wel eens van gehoord, maar kent het niet en 44% heeft er nog nooit van gehoord. -

Concept-Zienswijzen Delft Op Ontwerpbegrotingen 2021 Gemeenschappelijke Regelingen

Annotatie griffie Delft Concept-zienswijzen Delft op ontwerpbegrotingen 2021 Gemeenschappelijke Regelingen Samenwerkende gemeenten Delft Overige deelnemers aan GR (Regionale kaderbrief 2021) Link naar agenda bespreking 4 juni 2020 (nog niet gepubli- - zienswijzen door andere gemeenten ceerd) Begrotingen en Jaarstukken Gemeenschappelijke regelingen Delft (per commissie) Sociaal Domein en Wonen GGD en VT Haaglanden Concept-zienswijze Delft Den Haag, Leidschendam-Voorburg, Midden-Delfland, Pijnacker-Nootdorp, Jaarstukken 2019 GGD en VT Rijswijk, Wassenaar, Westland, Haaglanden Zoetermeer Servicebureau Jeugdhulp Haaglanden Concept-zienswijze Delft uiterlijk Den Haag, Leidschendam-Voorburg, (Inkoopbureau H10) 15 juni indienen Midden-Delfland, Pijnacker-Nootdorp, Rijswijk, Wassenaar, Westland, Jaarstukken? Zoetermeer, Voorschoten Ruimte en Verkeer Afvalinzameling Avalex Concept-zienswijze Delft Leidschendam-Voorburg, Midden- Delfland, Pijnacker-Nootdorp, Rijswijk, Wassenaar Omgevingsdienst Haaglanden (ODH) Concept-zienswijze Delft Den Haag, Leidschendam-Voorburg, Midden-Delfland, Pijnacker-Nootdorp, Rijswijk, Wassenaar, Westland, Zoetermeer, Provincie Zuid-Holland Economie, Financiën en Bestuur Veiligheidsregio Haaglanden (VRH) Concept-zienswijze Delft Den Haag, Leidschendam-Voorburg, Midden-Delfland, Pijnacker-Nootdorp, Rijswijk, Wassenaar, Westland, Zoetermeer Metropoolregio Rotterdam Den Haag Concept-zienswijze Delft Den Haag, Leidschendam-Voorburg, (MRDH) Midden-Delfland, Pijnacker-Nootdorp, Rijswijk, Wassenaar, Westland, MRDH Voorlopige -

Op Het Spoor Van De Gouwe Profielwerkstuk Over Het Onderzoek Naar De Loop Van De Rivier De Gouwe in De Goudse Binnenstad Rond 1200

COORNHERT GYMNASIUM GOUDA Op het spoor van de Gouwe Profielwerkstuk over het onderzoek naar de loop van de rivier de Gouwe in de Goudse binnenstad rond 1200. Erik‐Jan Dros, Jasper Schakel, Erik Kroon 15‐02‐2011 D.m.v. een bronnenonderzoek proberen ondergetekenden de loop van de Gouwe en mogelijk de aard van de verschillende veenlagen in de binnenstad vast te stellen. Pagina 2 van 72 Inhoudsopgave Doel van het onderzoek..……………………………………………………….. 4 Inleiding………………………………………………………………………… 4 Conclusie………………………………………………………………………... 5 Deel I: Het bronnenonderzoek……………………………….……….………. 11 Theorie vooraf…………………………………………………………… 12 Hypothese……………………………………………………….………. 13 Werkwijze……………………………………………………….………. 14 Resultaten……………………………………………………………….. 14 Bouwwerken……………………………………………………. 15 Haven……………………………………………………. 15 Donkere sluis…………………………………………….. 16 St. Janskerk……………………………………………… 17 Dubbele Buurt…………………………………………… 19 Motte……………………………………………………. 20 Verkaveling……………………………………………………… 21 Toponiemen……………………………………………………… 23 Deelconclusie.…………………………………………………………… 25 Discussie………………………………………………………………… 26 Deel II: De boormonsteranalyse……………………………………………… 27 Doel van de proef…..……………………………………………………. 28 Inleiding………….…………………………………………………….... 28 Overzicht van de monsters…….……………………………….... 28 Benodigdheden…………………………………………………………. 28 Proefopstelling…………………………………………………... 29 Werkwijze………………………………………………………………. 30 Resultaten……………………………………………………………….. 31 Deelconclusie…………………………………………………………….. 37 Discussie…………………………………………………………………. 38 Deel III: Analyse veensoorten in boormonsters..……………………………… -

Participatiekaart Zuid-Holland Zuid

Participatiekaart Burger- en cliëntenparticipatie Wmo Drechtsteden 20161 De gemeenten in de Drechtsteden willen een sterke positie van cliënten, mantelzorgers en inwoners in de beïnvloeding van beleid en uitvoering, zowel op Drechtstedenniveau als in elk van de zes afzonderlijke gemeenten. Een overzicht van alle organisaties die actief zijn op het gebied van cliëntenparticipatie en belangenbehartiging is hierbij een goed hulpmiddel. In de hiernavolgende Participatiekaart Wmo Drechtsteden vindt u dit overzicht. Zorgbelang Zuid-Holland heeft deze Participatiekaart samengesteld. De opzet is als volgt: Tabel 1: de cliëntenraden van de zorgorganisaties die in de regio Drechtsteden actief zijn. Het gaat om organisaties die landelijk, regionaal of lokaal werken. Tabel 2: landelijke cliënten(belangen)organisaties met lokale afdelingen en de regionale en lokale belangenbehartigersorganisaties; Tabel 3: de Wmo-adviesraden in de regio. De korte toelichting bij elke organisatie biedt inzicht in de doelstelling en achtergrond. Aan de hand van de Participatiekaart kunt u zien welke cliëntenraad, Wmo adviesraad of belangenbehartigersorganisatie in de regio of in uw gemeente actief is. Verzoek aanvullingen of wijzigingen Ziet u in het overzicht informatie die niet (meer) klopt of heeft u aanvullingen, wilt u die dan door geven aan Nelleke Schelfhout, [email protected] 1 De Participatiekaart is mogelijk gemaakt door de gemeenten in de Drechtsteden. Geactualiseerde versie 2 januari 2017 Pagina 1 van 17 1. Landelijke, regionale en lokale zorgorganisaties (op alfabetische volgorde) Organisatie Werkgebied Contactgegevens cliëntenraad Taak (en eventuele contactpersoon) Aafje Thuiszorg in Secretaresse Cliëntenraad Drechtsteden: Dordrecht e.o. Sylvia van Prooijen zorgorganisatie met Langeweg 340 thuiszorg, huizen en 3331 LZ Zwijndrecht zorghotels 088 823 10 00 [email protected] Agathos Thuiszorg o.a. -

Through the Netherlands by Bike & Boat

Through the Netherlands by Bike & Boat MS SIR WINSTON "South Holland" Characteristics: Operator: SE-TOURS GmbH Participants: from 40 up to 68 Tourtype: guided Children: no Regions: Amsterdam, Gouda, Lake Yssel, Meuse, North Holland, North Sea, Rhine, Rotterdam, South Holland, The Hague, Utrecht Countries: Netherlands Benefits: Seven nights in outside cabins shower/WC in the booked cabin category Programme according to routing from/to Amsterdam Welcome cocktail Room cleaning every day Changing of towels and bed cloths if wanted Full board consisting of breakfast buffet, snack on board or lunch package for cycling tours, coffee and tea in the afternoon, dinner Printed instructions and detailed maps for daily individual bike tours (1 per cabin) Daily meeting for the cycle tours Tour guide Rental bike insurance Additional costs: All other costs: on request (bikehire, cabin categories, additional nights, transfers and so on) Tour description: Discover the Netherlands in a unique way on an 8-days-journey by bike and boat. Well-built cycle paths as well as wide and extensive waterways guarantee an unforgettable holiday. Throughout the day you are cycling on your own through the beautiful landscapes in Rembrandt's and Van Gogh's country and in the late afternoon your swimming hotel MS SIR WINSTON will be at your disposal. And if you don't like to cycle every day, you can stay on board and enjoy the passing countryside. MS SIR WINSTON: Boat & Bike | Mittelstraße 9, 53332 Bornheim (Germany) | [email protected] | Phone: +49 (0)22 27 92 43 41 A cosy river boat with restaurant and bar, 2014 renovated (with air condition).