Tolerance of Cultural Diversity in Poland and Its Limitations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM UVM Honors College Senior Theses Undergraduate Theses 2018 Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany William Peter Fitz University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses Recommended Citation Fitz, William Peter, "Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany" (2018). UVM Honors College Senior Theses. 275. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses/275 This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in UVM Honors College Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REACTIONARY POSTMODERNISM? NEOLIBERALISM, MULTICULTURALISM, THE INTERNET, AND THE IDEOLOGY OF THE NEW FAR RIGHT IN GERMANY A Thesis Presented by William Peter Fitz to The Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Bachelor of Arts In European Studies with Honors December 2018 Defense Date: December 4th, 2018 Thesis Committee: Alan E. Steinweis, Ph.D., Advisor Susanna Schrafstetter, Ph.D., Chairperson Adriana Borra, M.A. Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter One: Neoliberalism and Xenophobia 17 Chapter Two: Multiculturalism and Cultural Identity 52 Chapter Three: The Philosophy of the New Right 84 Chapter Four: The Internet and Meme Warfare 116 Conclusion 149 Bibliography 166 1 “Perhaps one will view the rise of the Alternative for Germany in the foreseeable future as inevitable, as a portent for major changes, one that is as necessary as it was predictable. -

Central and Eastern Europe Development Outlook After the Coronavirus Pandemic

CHINA-CEE INSTITUTE CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE DEVELOPMENT OUTLOOK AFTER THE CORONAVIRUS PANDEMIC Editor in Chief: Dr. Chen Xin Published by: China-CEE Institute Nonprofit Ltd. Telephone: +36-1-5858-690 E-mail: [email protected] Webpage: www.china-cee.eu Address: 1052, Budapest, Petőfi Sándor utca 11. Chief Editor: Dr. Chen Xin ISSN: 978-615-6124-29-6 Cover design: PONT co.lab Copyright: China-CEE Institute Nonprofit Ltd. The reproduction of the study or parts of the study are prohibited. The findings of the study may only be cited if the source is acknowledged. Central and Eastern Europe Development Outlook after the Coronavirus Pandemic Chief Editor: Dr. Chen Xin CHINA-CEE INSTITUTE Budapest, October 2020 Content Preface ............................................................................................................ 5 Part I POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT OUTLOOK ..................................... 7 Albanian politics in post-pandemic era: reshuffling influence and preparing for the next elections .............................................................................................. 8 BiH political outlook after the COVID-19 pandemic ...................................... 13 Bulgarian Political Development Outlook in Post-Pandemic Era ..................... 18 Forecast of Croatian Political Events after the COVID-19 .............................. 25 Czech Political Outlook for the Post-Crisis Period .......................................... 30 Estonian political outlook after the pandemic: Are we there yet? ................... -

Deputy TABLE of CONT",Ci;NTS

iU~ CRIlviES and CRIlvIES i~Gi..INST HUlv1:~rITY l'..ffiT VI GEID~ll'JIS.""TION OF OCCUPIED TSRRITORIES l'repared by: 1st LT. ED:l.,'UtD H. KENYON I'R1i:.SElJTED BY SECTION IT H..JillY ~l. HOLLERS. Colonel. J •.u .•G.D. Chief'of S·.. ction iiILLL' ,~ F. ~£t:.LSH. Major, ...... C., Deputy TABLE OF CONT",ci;NTS Pa(_;e No. A. Suction of Indictr,lCnt 1 1 C. St~tmJent of Evidence 1. Leb~nsrallin as the Goal of Nazi Forei~n 2 Policy. 2. CO:lsi)iracy to COil4.Uer and Geroanise 2 ForeiGn Territories. 3. The Office of Reich Commissioner for 5 the Consolidation of Jerman Nationhood. 4. DCJ.sic T:'_eories and Plans of the Reich 7 CQj".::issioner for the Consolidation of G-:)l'r:an NLtionhood. 5. Gcr:'lunisation of the Incorl')orated 8 E~stern Territories. 6. Gcrr-l£;ilisation of the Gov9rnment 12 General. 7. GU1~lanisation of the Occupied Eastern 16 Territories. 8. Evacuation and R~sett10ment in the 18 Eusturn Territories. 9. Gorl::f:iiisc.tion of the :18~tern Terri- 21 tories. D. ,,-"r:.:,unent and. Conclusion. 25 1. N~erical List of Doc~~ents. 26 2. Ducuo,lents pertaining to Individual 30 Defendants. 3. Documents pertaining to Organizations. 30 i Section of I~dictBent COUNT TEREE - ii..J\ CRIMES VIII.J - Geruanisation of Occupied Territories Pace 24 B. Le~cl Ruf~rence5 1. C;iarter - oI.4r'ticle 6 (b): W,j..".lR CRTIvIES: nanelyI violations of the laws or customs of war. Such viol~tions shall include, but not be limited to, murder, ill-treatment or deportation to slave labor or for any other pur pose of civilian population of or in occupied territory, murder or ill-treatment of prisoners of war or persons on the seas, killing of hos tages, plunder of public or private property, wanton destruction of cities, to~ms or villages, or devastation not justified by military necessity." 2. -

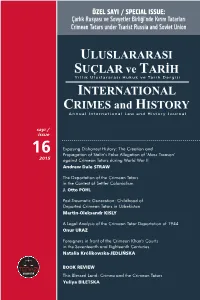

Ust Dergi Sayi 16 Layout 1

ÖZEL SAYI / SPECIAL ISSUE: Çarlık Rusyası ve Sovyetler Birliği’nde Kırım Tatarları Crimean Tatars under Tsarist Russia and Soviet Union ULUSLARARASI SUÇLAR ve TARİH Yıllık Uluslararası Hukuk ve Tarih Dergisi INTERNATIONAL CRIMES and HISTORY Annual International Law and History Journal sayı / issue 16 Exposing Dishonest History: The Creation and Propagation of Stalin’s False Allegation of ‘Mass Treason’ 2015 against Crimean Tatars during World War II Andrew Dale STRAW The Deportation of the Crimean Tatars in the Context of Settler Colonialism J. Otto POHL Post-Traumatic Generation: Childhood of Deported Crimean Tatars in Uzbekistan Martin-Oleksandr KISLY A Legal Analysis of the Crimean Tatar Deportation of 1944 Onur URAZ Foreigners in front of the Crimean Khan's Courts in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries Natalia Królikowska-JEDLIŃSKA BOOK REVIEW This Blessed Land: Crimea and the Crimean Tatars Yuliya BILETSKA ULUSLARARASI SUÇLAR VE TARİH INTERNATIONAL CRIMES AND HISTORY Yıllık Uluslararası Hakemli Dergi Annual International Peer-Reviewed Journal 2015, Sayı / Issue: 16 ISSN: 1306-9136 EDİTÖR / EDITOR E. Büyükelçi - Ambassador (R) Ömer Engin LÜTEM SORUMLU YAZI İŞLERİ MÜDÜRÜ / MANAGING EDITOR Dr. Turgut Kerem TUNCEL İMTİYAZ SAHİBİ / LICENSEE AVRASYA BİR VAKFI (1993) Bu yayın, Avrasya Bir Vakfı adına, Avrasya İncelemeleri Merkezi tarafından hazırlanmaktadır. This publication is edited by Center for Eurasian Studies on behalf of Avrasya Bir Vakfı. YAYIN KURULU / EDITORIAL BOARD Alfabetik Sıra ile / In Alphabetic Order Prof. Dr. Dursun Ali AKBULUT E. Büyükelçi / Ambassador (R) Alev KILIÇ (Ondokuz Mayıs Üniversitesi) (Avrasya İncelemeleri Merkezi Başkanı) Prof. Dr. Ayşegül AYDINGÜN E. Büyükelçi / Ambassador (R) Ömer Engin LÜTEM (Orta Doğu Teknik Üniversitesi) (Avrasya İncelemeleri Merkezi Onursal Başkanı) Prof. -

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth As a Political Space: Its Unity and Complexity*

Chapter 8 The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth as a Political Space: Its Unity and Complexity* Satoshi Koyama Introduction The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (Rzeczpospolita) was one of the largest states in early modern Europe. In the second half of the sixteenth century, after the union of Lublin (1569), the Polish-Lithuanian state covered an area of 815,000 square kilometres. It attained its greatest extent (990,000 square kilometres) in the first half of the seventeenth century. On the European continent there were only two larger countries than Poland-Lithuania: the Grand Duchy of Moscow (c.5,400,000 square kilometres) and the European territories of the Ottoman Empire (840,000 square kilometres). Therefore the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was the largest country in Latin-Christian Europe in the early modern period (Wyczański 1973: 17–8). In this paper I discuss the internal diversity of the Commonwealth in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and consider how such a huge territorial complex was politically organised and integrated. * This paper is a part of the results of the research which is grant-aided by the ‘Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research’ program of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science in 2005–2007. - 137 - SATOSHI KOYAMA 1. The Internal Diversity of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth Poland-Lithuania before the union of Lublin was a typical example of a composite monarchy in early modern Europe. ‘Composite state’ is the term used by H. G. Koenigsberger, who argued that most states in early modern Europe had been ‘composite states, including more than one country under the sovereignty of one ruler’ (Koenigsberger, 1978: 202). -

Language Contact in Pomerania: the Case of German, Polish, and Kashubian

P a g e | 1 Language Contact in Pomerania: The Case of German, Polish, and Kashubian Nick Znajkowski, New York University Purpose The effects of language contact and language shift are well documented. Lexical items and phonological features are very easily transferred from one language to another and once transferred, rather easily documented. Syntactic features can be less so in both respects, but shifts obviously do occur. The various qualities of these shifts, such as whether they are calques, extensions of a structure present in the modifying language, or the collapsing of some structure in favor the apparent simplicity found in analogous foreign structures, all are indicative of the intensity and the duration of the contact. Additionally, and perhaps this is the most interesting aspect of language shift, they show what is possible in the evolution of language over time, but also what individual speakers in a single generation are capable of concocting. This paper seeks to explore an extremely fascinating and long-standing language contact situation that persists to this day in Northern Poland—that of the Kashubian language with its dominating neighbors: Polish and German. The Kashubians are a Slavic minority group who have historically occupied the area in Northern Poland known today as Pomerania, bordering the Baltic Sea. Their language, Kashubian, is a member of the Slavic branch of Indo-European languages and further belongs to the Pomeranian branch of Lechitic languages, which includes Polish, Silesian, and the extinct Polabian and Slovincian. The situation to be found among the Kashubian people, a people at one point variably bi-, or as is sometimes the case among older folk, even trilingual in Kashubian, P a g e | 2 Polish, and German is a particularly exciting one because of the current vitality of the Kashubian minority culture. -

59 Concepts of Moral Education in Poland Stefan Konstańczak

Ethics & Bioethics (in Central Europe), 2016, 6 (1–2), 59–68 DOI:10.1515/ebce-2016-0009 Concepts of moral education in Poland Stefan Konstańczak Abstract In this article the author presents the contemporary understanding of the subject of moral education. Furthermore, he presents the historical development of the concept of moral education in Poland. He concludes that the current model of moral education in Poland was developed as early as the 18th century. Keywords: moral upbringing, moral education, history of moral education in Poland, concepts of moral education in Poland. Introduction Education is a specific sphere of human life. It cannot be limited only to the dimension of the individual as his being is a teacher-pupil relationship. The transfer of values from the teacher to the pupil is of particular importance since the teacher becomes a spokesman for society and equips others with knowledge and skills which are necessary for the pupil to become a useful member of a particular community. This process takes place on many levels including moral, aesthetic, health, physical, civil, and sexual (Zarzecki, 2012, p. 113).1 However, for society, moral education is of paramount importance because outside the intellectual sphere, the spheres of volition and emotion are shaped in the young generation. The term “moral education” is not universally accepted in Polish pedagogical and philosophical literature. Parallel terms like “ethical education” and “value-based education” (Łobocki, 2006, pp. 11–12) exist with identical meanings. This emphasizes that, in principle, every educational process is related to moral education because during its course the pupil is both taught and drilled to observe the norms and values in a given society. -

A Synthetic Analysis of the Polish Solidarity Movement Stephen W

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 1-1-2011 A Synthetic Analysis of the Polish Solidarity Movement Stephen W. Mays [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the Other Political Science Commons, and the Politics and Social Change Commons Recommended Citation Mays, Stephen W., "A Synthetic Analysis of the Polish Solidarity Movement" (2011). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 73. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A SYNTHETIC ANALYSIS OF THE POLISH SOLIDARITY MOVEMENT A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Sociology by Stephen W. Mays Approved by Dr. Richard Garnett, Committee Chairman Dr. Marty Laubach Dr. Brian Hoey Marshall University Huntington, West Virginia December 2011 Table Of Contents Page Acknowledgements ................................................................................ iii Abstract .................................................................................................. v Chapter I. Introduction ................................................................................... 1 II. Methodology .................................................................................. -

Dialect Contact and Convergence in Contemporary Hutsulshchyna By

Coming Down From the Mountain: Dialect Contact and Convergence in Contemporary Hutsulshchyna By Erin Victoria Coyne A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Johanna Nichols, Chair Professor Alan Timberlake Professor Lev Michael Spring 2014 Abstract Coming Down From the Mountain: Dialect Contact and Convergence in Contemporary Hutsulshchyna by Erin Victoria Coyne Doctor of Philosophy in Slavic Languages and Literatures University of California, Berkeley Professor Johanna Nichols, Chair Despite the recent increased interest in Hutsul life and culture, little attention has been paid to the role of dialect in Hutsul identity and cultural revival. The primary focus of the present dissertation is the current state of the Hutsul dialect, both in terms of social perception and the structural changes resulting from the dominance of the standard language in media and education. Currently very little is known about the contemporary grammatical structure of Hutsul. The present dissertation is the first long-term research project designed to define both key elements of synchronic Hutsul grammar, as well as diachronic change, with focus on variation and convergence in an environment of increasing close sustained contact with standard Ukrainian resulting from both a historically-based sense of ethnic identification, as well as modern economic realities facing the once isolated and self-sufficient Hutsuls. In addition, I will examine the sociolinguistic network lines which allow and impede linguistic assimilation, specifically in the situation of a minority population of high cultural valuation facing external linguistic assimilation pressures stemming from socio-political expediency. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1937, No.5

www.ukrweekly.com JtegjglgngjMgnflig SVOBOPA,U^btoian- Ibtiy FnMfehei by the Junior Department of the Ukrainian National Association „-! '-,•. !-L_ No. 5 JERSEY CTTY, N. J. SATURDAY, JANUARY, 30, 1937 VOL. V BW ,"." ". і і її.• » HISTORY OF UKRAINIAN MIL UKRAINIAN-AMERICAN/ A LESSON OF TWENTY YEARS AGO ITARY FORCES - PUBLISHED ARTISTS ORGANIZE p Twenty winters ago there-was lit on the thronged A work that is invaluable and Of apecial interest to all our streets of Petrograd the firebrand of revolution- Fanned by far the best of Its kind thus Ukrainian-Americans who are by winds- of discontent, born of unmitigated oppression far is the. newly-published oae- actively interested in the various and appalling porruption, the flickering flames quickly volume "Istoriya Ukrainskoho branches of art, such as painting changed into a. raging inferno that enveloped the entire Viyeka" (History of Ukrainian • and sculpture, is the recent hews Military, Forces),, containing, 668 that a group of "th*m in New "prison house ofVnatiqps"-4Caarist Russia.. pages, 383 mirations, and ;4 . York City ha?- laid plans for the The. breaking out of the Russian. Revolution was colored, .РЦ^ея. creation of a Society of Ukrain- ha-rdiy. a surprise to any careful observer. It had been The work represents cooperative ian-American Artiste. long-expected, and even prepared for by many. effort on . the' part-, ol several " The meeting at which these Among the Ukrainians, too, prophetic voices concern authorities in. this. field. Part I plane were first drawn and ing Tik had long been heard. Such patriots,, as. Mfkola and, Ц, encompassing the •Kievan formally discussed was' held last . -

Gazeta Winter 2016

Chaim Goldberg, Purim Parade, 1993, oil painting on canvas Volume 23, No. 1 Gazeta Winter 2016 A quarterly publication of the American Association for Polish-Jewish Studies and Taube Foundation for Jewish Life & Culture Editorial & Design: Fay Bussgang, Julian Bussgang, Shana Penn, Vera Hannush, Alice Lawrence, Maayan Stanton, LaserCom Design. Front Cover Photo: Chaim Goldberg; Back Cover Photo: Esther Nisenthal Krinitz J.D. Kirszenbaum, Self-portrait, c. 1925, oil on canvas TABLE OF CONTENTS Message from Irene Pipes ............................................................................................... 1 Message from Tad Taube and Shana Penn ................................................................... 2 RESEARCH PROJECT The Holocaust in the Eyes of Polish Youth By Dr. Jolanta Ambrosewicz-Jacobs .................................................................................. 3 ART AS FAMILY LEGACY A Daughter Returns with Memories in Art By Bernice Steinhardt .......................................................................................................... 7 Resurrection of a Painter: “From Staszów to Paris, via Weimar, Berlin and Rio de Janeiro” By Nathan Diament ........................................................................................................... 12 Creating a New Museum in Kazimierz By Shalom Goldberg ......................................................................................................... 16 CONFERENCES, SPRING/SUMMER PROGRAMS, AND FESTIVALS Conference on Launch of Volume -

Employment in Poland 2009 Entrepreneurship for Work

Employment in Poland 2009 Entrepreneurship for work Edited by Maciej Bukowski Warsaw 2010 Authors Editor: Maciej Bukowski, PhD Part I Maciej Bukowski, PhD Piotr Lewandowski Part II Sonia Buchholtz Łukasz Skrok Part III Jan Gąska Piotr Lewandowski Part IV Maciej Bukowski, PhD Horacy Dębowski Co-operation: Maciej Lis, Maciej Małysz, Andrzej Żurawski All opinions and conclusions included in this publication constitute the authors’ views and do not necessarily refl ect the offi cial position of the Ministry of Labour and Social Policy. This report was prepared as part of the project Analysis of the labour market processes and social integration in Poland in the context of economic policy carried out by the Human Resources Development Centre, co-fi nanced by the European Social Fund and initiated by the Department of Economic Analyses and Forecasts at the Ministry of Labour and Social Policy, by: Institute for Structural Research (Instytut Badań Strukturalnych) Rejtana 15, r. 24/25 02-516 Warszawa, Poland e-mail: [email protected] www.ibs.org.pl Reytech Rejtana 15, r. 25 02-516 Warszawa, Poland e-mail: [email protected] www.reytech.pl Field survey: ASM Market Research and Analysis Centre Ltd. Grunwaldzka 5, 99-301 Kutno Cover design, typesetting and editing graphic studio Temperówka www.temperowka.pl This publication was co-fi nanced by the European Union under the European Social Fund © Copyright by Human Resources Development Centre ISBN: 978-83-61638-17-9 5 Introduction 7 Part I Labour market in the business cycle 41 Part II Quality of working life – traditional and modern sectors of the economy 91 Part III Procedures and regulations – on hirings and dismissals 131 Part IV Social dialogue in the changing labour market 177 Recommendations for social and economic policy 181 Methodological Appendix 193 Bibliography Introduction The report ‘Employment in Poland 2009 – Entrepreneurship for Work’ is the fi fth edition of the Employment in Poland series, a thorough study of the most signifi cant processes occurring in the Polish and European labour markets.