Broadcasting Bill [H.L.] [Bill 88 1995/96]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Register of Journalists' Interests

REGISTER OF JOURNALISTS’ INTERESTS (As at 11 July 2018) INTRODUCTION Purpose and Form of the Register Pursuant to a Resolution made by the House of Commons on 17 December 1985, holders of photo- identity passes as lobby journalists accredited to the Parliamentary Press Gallery or for parliamentary broadcasting are required to register: ‘Any occupation or employment for which you receive over £770 from the same source in the course of a calendar year, if that occupation or employment is in any way advantaged by the privileged access to Parliament afforded by your pass.’ Administration and Inspection of the Register The Register is compiled and maintained by the Office of the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards. Anyone whose details are entered on the Register is required to notify that office of any change in their registrable interests within 28 days of such a change arising. An updated edition of the Register is published approximately every 6 weeks when the House is sitting. Changes to the rules governing the Register are determined by the Committee on Standards in the House of Commons, although where such changes are substantial they are put by the Committee to the House for approval before being implemented. Complaints Complaints, whether from Members, the public or anyone else alleging that a journalist is in breach of the rules governing the Register, should in the first instance be sent to the Registrar of Members’ Financial Interests in the Office of the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards. Where possible the Registrar will seek to resolve the complaint informally. In more serious cases the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards may undertake a formal investigation and either rectify the matter or refer it to the Committee on Standards. -

DICE Best Practice Guide.Pdf

BEST PRACTICE GUIDE Interactive Service, Frequency Social Business Migration, Policy & Platforms Acceptance Models Implementation Regulation & Business Opportunities BEST PRACTICE GUIDE FOREWORD As Lead Partner of DICE I am happy to present this We all want to reap the economic benefi ts of dig- best practice guide. Its contents are based on the ital convergence. The development and successful outputs of fi ve workgroups and countless discus- implementation of new services need extended sions in the course of the project and in conferences markets, however; markets which often have to be and workshops with the broad participation of in- larger than those of the individual member states. dustry representatives, broadcasters and political The sooner Europe moves towards digital switcho- institutions. ver the sooner the advantages of released spectrum can be realised. The DICE Project – Digital Innovation through Co- operation in Europe – is an interregional network We have to recognise that a pan-European telecom funded by the European Commission. INTERREG as and media industry is emerging. The search for an EU community initiative helps Europe’s regions economies of scale is driving the industry into busi- form partnerships to work together on common nesses outside their home country and to strategies projects. By sharing knowledge and experience, beyond their national market. these partnerships enable the regions involved to develop new solutions to economic, social and envi- It is therefore a pure necessity that regional political ronmental challenges. institutions look across the border and aim to learn from each other and develop a common under- DICE focuses on facilitating the exchange of experi- standing. -

LTE Interference Into Domestic Digital Television Systems

Page 1 of 132 Business Unit: Cobham Technical Services ERA Technology RF and EMC Group Report Title: LTE Interference into Domestic Digital Television Systems Author(s): Bal Randhawa Ian Parker Samuel Antwi Client: Ofcom Client Reference: Graham Warren Report Number: 2010-0026 (Issue 2) Project Number: 7A0513004 Report Version: Final Report Report Checked by: Approved by: S Munday M Ganley Head of RF Assessment Head of RF & EMC Group January 2010 Ref. SPM/vs/62/05130/Rep-6537 Cobham Technical Services ERA Technology Report 2010-0026 (Issue 2) © Copyright ERA Technology Limited 2010 All Rights Reserved No part of this document may be copied or otherwise reproduced without the prior written permission of ERA Technology Limited. If received electronically, recipient is permitted to make such copies as are necessary to: view the document on a computer system; comply with a reasonable corporate computer data protection and back-up policy and produce one paper copy for personal use. DOCUMENT CONTROL If no restrictive markings are shown, the document may be distributed freely in whole, without alteration, subject to Copyright. ERA Technology Limited trading as Cobham Technical Services Cleeve Road Leatherhead Surrey KT22 7SA, England Tel : +44 (0) 1372 367000 Fax: +44 (0) 1372 367099 E-mail: [email protected] Read more about Cobham Technical Services on our Internet page at: www.cobham.com/technicalservices Ref: P:\Projects Database\Ofcom 2009 - 7x 05130\Ofcom - 7A0513004 - LTE UMTS mobile interference\ERA Reports\Rep-6537 - 2010-0026 (Issue 2).doc 2 © ERA Technology Ltd Cobham Technical Services ERA Technology Report 2010-0026 (Issue 2) Summary As part of the Digital Dividend Review (DDR), Ofcom commissioned Cobham Technical Services – ERA Technology to carry out a measurement study in order to answer the following questions: 1. -

Cover Sheet for Response to an Ofcom Consultation BASIC DETAILS

Cover sheet for response to an Ofcom consultation BASIC DETAILS Consultation title: Draft Annual Plan 2014/15 To (Ofcom contact): Puja Kalaria Name of respondent: Richard Lindsay-Davies Representing (self or organisation/s): Digital TV Group Address (if not received by email): CONFIDENTIALITY Please tick below what part of your response you consider is confidential, giving your reasons why X Nothing Name/contact details/job title Whole response Organisation Part of the response If there is no separate annex, which parts? If you want part of your response, your name or your organisation not to be published, can Ofcom still publish a reference to the contents of your response (including, for any confidential parts, a general summary that does not disclose the specific information or enable you to be identified)? DECLARATION I confirm that the correspondence supplied with this cover sheet is a formal consultation response that Ofcom can publish. However, in supplying this response, I understand that Ofcom may need to publish all responses, including those which are marked as confidential, in order to meet legal obligations. If I have sent my response by email, Ofcom can disregard any standard e-mail text about not disclosing email contents and attachments. Ofcom seeks to publish responses on receipt. If your response is non-confidential (in whole or in part), and you would prefer us to publish your response only once the consultation has ended, please tick here. Name Richard Lindsay-Davies Signed (if hard copy) DTG response to: Ofcom “Draft Annual Plan 2014/15 Friday 14 February 2014 Ofcom: Draft Annual Plan 2014/15 The Digital TV Group (DTG) welcomes the opportunity to respond to the above consultation regarding Ofcom’s draft proposals for their priorities and work areas in the financial year 2014/15. -

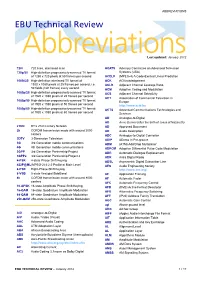

ABBREVIATIONS EBU Technical Review

ABBREVIATIONS EBU Technical Review AbbreviationsLast updated: January 2012 720i 720 lines, interlaced scan ACATS Advisory Committee on Advanced Television 720p/50 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format Systems (USA) of 1280 x 720 pixels at 50 frames per second ACELP (MPEG-4) A Code-Excited Linear Prediction 1080i/25 High-definition interlaced TV format of ACK ACKnowledgement 1920 x 1080 pixels at 25 frames per second, i.e. ACLR Adjacent Channel Leakage Ratio 50 fields (half frames) every second ACM Adaptive Coding and Modulation 1080p/25 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format ACS Adjacent Channel Selectivity of 1920 x 1080 pixels at 25 frames per second ACT Association of Commercial Television in 1080p/50 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format Europe of 1920 x 1080 pixels at 50 frames per second http://www.acte.be 1080p/60 High-definition progressively-scanned TV format ACTS Advanced Communications Technologies and of 1920 x 1080 pixels at 60 frames per second Services AD Analogue-to-Digital AD Anno Domini (after the birth of Jesus of Nazareth) 21CN BT’s 21st Century Network AD Approved Document 2k COFDM transmission mode with around 2000 AD Audio Description carriers ADC Analogue-to-Digital Converter 3DTV 3-Dimension Television ADIP ADress In Pre-groove 3G 3rd Generation mobile communications ADM (ATM) Add/Drop Multiplexer 4G 4th Generation mobile communications ADPCM Adaptive Differential Pulse Code Modulation 3GPP 3rd Generation Partnership Project ADR Automatic Dialogue Replacement 3GPP2 3rd Generation Partnership -

Digital TV Group (DTG) Response: Ofcom Consultation on 'Securing

Digital TV Group response: Ofcom consultation on ‘Securing long term benefits for scarce spectrum resources – a strategy for UHF bands IV and V’ 07 June 2012 Digital TV Group (DTG) response: Ofcom consultation on ‘Securing long term benefits for scarce spectrum resources – a strategy for UHF bands IV and V’ 07 June 2012 Executive Summary The Digital TV Group (DTG) recognises that there will be increasing demands on UHF spectrum in the near future, and that it is particularly important that this spectrum is used effectively and efficiently for the maximum benefit to UK consumers and industry. The DTG is keen to assist with the introduction of emerging technologies in order to facilitate greater efficiency; while also recognising that digital terrestrial television (DTT) is relied upon by many consumers who have high expectations of its continued development and future integrity. The deployment of new technologies that make use of spectrum in UHF bands IV and V must be carefully planned and managed to ensure coexistence with DTT if the UK. It is important that neither the quality of existing DTT services or the emerging technologies making use of this spectrum are compromised if the UK is to benefit fully from new and efficient uses of spectrum whilst maintaining its global reputation for innovation. Response 1. The DTG’s response relates principally to questions 15 to18 on the possible clearance of digital terrestrial television (DTT) from channels 49-60 and its reintroduction to channels 31-37, and to questions 19 and 20 on the short term use of channels 31-37. -

Société, Information Et Nouvelles Technologies: Le Cas De La Grande

Société, information et nouvelles technologies : le cas de la Grande-Bretagne Jacqueline Colnel To cite this version: Jacqueline Colnel. Société, information et nouvelles technologies : le cas de la Grande-Bretagne. Sciences de l’information et de la communication. Université de la Sorbonne nouvelle - Paris III, 2009. Français. NNT : 2009PA030015. tel-01356701 HAL Id: tel-01356701 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01356701 Submitted on 26 Aug 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. UNIVERSITE SORBONNE NOUVELLE – PARIS 3 UFR du Monde Anglophone THESE DE DOCTORAT Discipline : Etudes du monde anglophone AUTEUR Jacqueline Colnel SOCIETE, INFORMATION ET NOUVELLES TECHNOLOGIES : LE CAS DE LA GRANDE-BRETAGNE Thèse dirigée par Monsieur Jean-Claude SERGEANT Soutenue le 14 février 2009 JURY : Mme Renée Dickason M. Michel Lemosse M. Michaël Palmer 1 REMERCIEMENTS Je remercie vivement Monsieur le Professeur Jean-Claude SERGEANT, mon directeur de thèse, qui a accepté de diriger mes recherches, m’a guidée et m’a prodigué ses précieux conseils avec bienveillance tout au long de ces années avec beaucoup de disponibilité. Mes remerciements vont aussi à ma famille et à mes amis qui m’ont beaucoup soutenue pendant cettre entreprise. -

The BBC's Distribution Arrangements for Its UK Public Services

The BBC’s distribution arrangements for its UK Public Services A report by Mediatique presented to the BBC Trust Finance Committee November 2013 BRITISH BROADCASTING CORPORATION The BBC’s distribution arrangements for its UK Public Services A report by Mediatique presented to the BBC Trust Finance Committee November 2013 Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport by Command of Her Majesty February 2014 © BBC 2013 The text of this document may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as BBC copyright and the document title specified. Where third party material has been identified, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought BBC Trust response to Mediatique’s value for money study: the BBC’s distribution arrangements for its UK Public Services Introduction The BBC exists to educate, inform and entertain through a broad range of high quality programmes and services on TV, Radio and Online. It is also tasked with distributing this content to audiences across the country in ways that are convenient to them. In 2012-13 the cost of these distribution arrangements was £233million or 6.5 percent of the licence fee. The BBC Trust exists to maximise the value audiences receive in return for the licence fee. To help it do this, the Trust commissioned Mediatique to carry out a value for money review of the BBC’s distribution arrangements in the UK. This is one of a number of value for money reports received by the Trust from various organisations, including the NAO, all of which help the Trust to identify ways to improve the way the BBC is run. -

Digital Solent Conference Report

Digital Solent Conference Report November 2017 Helping make the Solent the UK’s leading region for digital business growth 1 Helping make the Solent the UK’s leading Digital Solent region for digital business growth 1.0 Introduction Page 3 1.1 About the Digital Solent Conference Page 4 1.2 Aims of the conference 2.0 Speaker sessions Page 5 2.1 Session 1: The Digital Landscape Page 10 2.2 Session 2: Business benefits of digital presence Page 15 2.3 Session 3: Cyber resilience- risks and opportunities 3.0 Innovation Challenges Page 19 3.1 Summaries of each challenge Page 39 3.2 Continuation of winning project Page 41 4.0 Debriefing and next steps See appendices for speaker bios and attendees list 2 Helping make the Solent the UK’s leading Digital Solent region for digital business growth 1.0 Introduction 1.1 About the Digital Solent Conference As part of the development of an ambitious programme of regeneration that seeks to transform local economic prospects, the Isle of Wight Council worked in conjunction with the Solent LEP and VentureFest South to hold the first Digital Solent Conference, which took place on the 8th November 2017. The event was held at Cowes Yacht Haven on the Isle of Wight and was attended by 159 delegates (see appendix 2). Attendees included local companies active in the digital sector on the Island and in the wider Solent region, secondary school pupils, Isle of Wight council cabinet members and a range of representatives (see appendix 1), who shared their digital knowledge, experience and expertise. -

DTG Response to Ofcom Consultation: Licensing Local Television – How Ofcom Would Exercise Its New Powers and Duties Being Proposed by Government 16Th March 2012

DTG Response to Ofcom Consultation: Licensing Local Television – How Ofcom would exercise its new powers and duties being proposed by Government 16th March 2012 The Digital TV Group’s (DTG) response to this consultation principally relates to the questions in 4.104, “Do you agree with our approach to technical standards? Do you have any views on the choice of transmission mode or encoding standards?” and to the paragraphs on technical standards, (4.98 to 4.103). In making its response, the DTG recognises that local TV will benefit viewers and may well strengthen the attractiveness of the digital terrestrial TV offering. It recognises that placing technical requirements for interoperability on the channel and multiplex operators could be seen as adding cost that might adversely affect those businesses. The DTG has therefore kept its recommendations to what it believes is the minimum required for interoperability. The Group believes that this level of interoperability will make local TV service accessible to the widest range of viewers and will therefore strengthen rather than weaken the business proposition. The DTG has also made some more general observations, and has identified which comments are firm recommendations for interoperability and which are observations. The DTG’s detailed comments and recommendations are as follows:- Ref Digital TV Group comment Supporting rationale for DTG Supporting evidence for DTG comment comment - how it benefits industry and/or viewers 1 Broadcast Technical Requirements: The To maximise the compatibility of The D-book provide the UK profiles of the international and European new services should comply with the the new TV services with the standards including ETSI EN 300 744. -

Making TELEVISION ACCESSIBLE REPORT NOVEMBER 2011 Making a TELEV CCESS DIGITAL INCLUSION Telecommunication Developmentsector NOVEMBER 2011 Report I

DIGITAL INCLUSION International Telecommunication Union Telecommunication Development Bureau OVEMBER 2011 N Place des Nations CH-1211 Geneva 20 Making Switzerland www.itu.int TELEVISION ACCESSIBLE Report REPORT BLE I CCESS A N O I S I NOVEMBER 2011 Printed in Switzerland MAKING TELEV Telecommunication Development Sector Geneva, 2011 11/2011 Making Television Accessible November 2011 This report is published in cooperation with G3ict – The Global Initiative for Inclusive Information and Communication Technologies, whose mission is to promote the ICT accessibility dispositions of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities www.g3ict.org. ITU and G3ict also co-produce the e-accessibility Policy Toolkit for Persons with Disabilities www.e-accessibilitytoolkit.org and jointly organize awareness raising and capacity building programmes for policy makers and stakeholders involved in accessibility issues around the world. This report has been prepared by Peter Olaf Looms, Chairman ITU-T Focus Group on Audiovisual Media Accessibility. ITU 2011 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, by any means whatsoever, without the prior written permission of ITU. Making Television Accessible Foreword Ensuring that all of the world’s population has access to television services is one of the targets set by world leaders in the World Summit on the Information Society. Television is important for enhancing national identity, providing an outlet for domestic media content and getting news and information to the public, which is especially critical in times of emergencies. Television programmes are also a principal source of news and information for illiterate segments of the population, some of whom are persons with disabilities. -

05-December-2012 Register of Sponsors Licensed Under the Points-Based System

REGISTER OF SPONSORS (Tiers 2 & 5 and Sub Tiers Only) DATE: 05-December-2012 Register of Sponsors Licensed Under the Points-based System This is a list of organisations licensed to sponsor migrants under Tiers 2 & 5 of the Points-Based System. It shows the organisation's name (in alphabetical order), the tier(s) they are licensed for, and whether they are A-rated or B-rated against each sub-tier. A sponsor may be licensed under more than one tier, and may have different ratings for each tier. No. of Sponsors on Register Licensed under Tiers 2 and 5: 25,750 Organisation Name Town/City County Tier & Rating Sub Tier (aq) Limited Leeds West Yorkshire Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General ?What If! Ltd London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General Tier 2 (A rating) Intra Company Transfers (ICT) @ Bangkok Cafe Newcastle upon Tyne Tyne and Wear Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General @ Home Accommodation Services Ltd London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General Tier 5TW (A rating) Creative & Sporting 1 Life London Limited London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 1 Tech LTD London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 100% HALAL MEAT STORES LTD BIRMINGHAM West Midlands Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 1000heads Ltd London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 1000mercis LTD London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General Tier 2 (A rating) Intra Company Transfers (ICT) 101 Thai Kitchen London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 101010 DIGITAL LTD NEWARK Page 1 of 1632 Organisation Name Town/City County Tier & Rating Sub Tier Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 108 Medical Ltd London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 111PIX.Com Ltd London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 119 West st Ltd Glasgow Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 13 Artists Brighton Tier 5TW (A rating) Creative & Sporting 13 strides Middlesbrough Cleveland Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 145 Food & Leisure Northampton Northampton Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 15 Healthcare Ltd London Tier 2 (A rating) Tier 2 General 156 London Road Ltd t/as Cake R us Sheffield S.