Myth and War in CS Lewis's Ransom Trilogy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CS Lewis on Death

Volume 1 Issue 2 Article 4 January 1971 Farewell to Shadowlands: C.S. Lewis on Death Kathryn Lindskoog Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythpro Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Lindskoog, Kathryn (1971) "Farewell to Shadowlands: C.S. Lewis on Death," Mythcon Proceedings: Vol. 1 : Iss. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythpro/vol1/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythcon Proceedings by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mythcon 51: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico • Postponed to: July 30 – August 2, 2021 Abstract Examines death as portrayed in many of Lewis’s fictional and apologetic writings, and particularly in the Chronicles of Narnia. Discusses Lewis’s attitudes toward his own impending death as expressed to friends and his brother Warren. Keywords Lewis, C.S.—Attitude toward death This article is available in Mythcon Proceedings: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythpro/vol1/iss2/4 Lindskoog: Farewell to Shadowlands: C.S. Lewis on Death suooestion has been made14 that the Nine corresponded to the nine 4. JJJ 383 planets. These would be Mercury, Venus, the Earth, the Hoon, S. III 456 Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune. Pluto •as probably not 6. I 472 known to the astronomers of the Second AQe; Neptune is not 7. -

<I>Screwtape Letters</I> and <I>The Great Divorce

Volume 17 Number 1 Article 7 Fall 10-15-1990 Immortal Horrors and Everlasting Splendours: C.S. Lewis' Screwtape Letters and The Great Divorce Douglas Loney Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Loney, Douglas (1990) "Immortal Horrors and Everlasting Splendours: C.S. Lewis' Screwtape Letters and The Great Divorce," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 17 : No. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol17/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Sees Screwtape and The Great Divorce as constituting “something like a sub-genre within the Lewis canon.” Both have explicit religious intention, were written during WWII, and use a “rather informal, episodic structure.” Analyzes the different perspectives of each work, and their treatment of the themes of Body and Spirit, Time and Eternity, and Love. -

The Face of the Materialist Magician: Lewis, Tolkien, and the Art of Crossing Perilous Streets

Volume 35 Number 1 Article 2 10-15-2016 The Face of the Materialist Magician: Lewis, Tolkien, and the Art of Crossing Perilous Streets Robert Boenig Texas A&M University in College Station, TX Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Boenig, Robert (2016) "The Face of the Materialist Magician: Lewis, Tolkien, and the Art of Crossing Perilous Streets," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 35 : No. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol35/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Plenary address, Mythcon 47. Concerns the character of the “Materialist Magician” (Screwtape’s term) in Tolkien and Lewis—the Janus-like figure who looks backward to magic and forward to scientism, without the moral core to reconcile his liminality. -

The Use of the Vertical Plane to Indicate Holiness in C.S. Lewis's Space Trilogy

Volume 34 Number 2 Article 3 4-15-2016 The Use of the Vertical Plane to Indicate Holiness in C.S. Lewis's Space Trilogy Sarah Eddings Northern Arizona University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Eddings, Sarah (2016) "The Use of the Vertical Plane to Indicate Holiness in C.S. Lewis's Space Trilogy," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 34 : No. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol34/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Examines the contrasting symbolism and imagery of perpendicular structures (mountains, trees, built structures, and so on) and waves in the Space Trilogy as a whole. Eddings finds more than simple gendered symbolism in these clusters of images; verticality indicates reaching for the heavens and waves show submission to the will of Maleldil. -

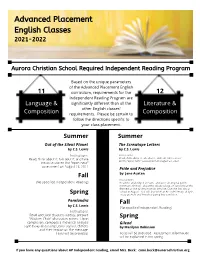

Required Independent Reading Program

Advanced Placement English Classes 2021-2022 Aurora Christian School Required Independent Reading Program Based on the unique parameters of the Advanced Placement English 11 curriculum, requirements for the 12 Independent Reading Program are Language & significantly different than all the Literature & other English classes' Composition requirements. Please be certain to Composition follow the directions specific to your class placement. Summer Summer Out of the Silent Planet The Screwtape Letters by C.S. Lewis by C.S. Lewis Instructions: Instructions: Read, think about it, talk abut it, and take Read, think about it, talk abut it, and take notes to use on the "open-note" assessment on August 23, 2021 notes to use on the "open-note" assessment on August 23, 2021 Pride and Prejudice Fall by Jane Austen Instructions: (No specified Independent Reading) Read the unabridged version, and write an original poem - minimum 30 lines - about the ideals, values, or concerns of the Bennets or the society in which they live. Due the first day of school in August. You will also write an AP style literary analysis Spring essay on Pride and Prejudice during first semester. Perelandra Fall by C.S. Lewis (No specified Independent Reading) Instructions: Read specified chapters weekly, prepare "Wisdom Chair" discussion points. Upon Spring completion, compose a rhetorical analysis Gilead style essay discussing Lewis' stylistic choices by Marilynn Robinson and their impact on the message. Texts will be provided. Texts will be provided. Assessment information will be explained in the spring. If you have any questions about AP Independent reading, email Mrs. Beck: [email protected].. -

SHADOWLANDS Introduction

SHADOWLANDS Introduction ‘Shadowlands’ tells of the extraordinary love between C. S. Lewis, the famous writer and Christian academic and Joy Gresham, an American poet who came to know him first through his writing. She was to die shortly after their marriage. ‘Shadowlands’ was first a television and then a stage play and is now a film starring Anthony Hopkins and Debra Winger. This guide is for use before and after a viewing of Richard Attenborough’s film. It seeks to expand for class work the themes of love and bereavement, the risks of emotional involvement and the challenge to all faiths of pain and tragedy as well as discussing the way film tackles these difficult subjects. JACK AND JOY Olive Staples Lewis - known always as Jack - was born in 1898 in Belfast three years after the Lewis’s first son, Warren or “Warnie”. The brothers were very close, and spent much of their adult bachelor life living together near Oxford in a ramshackle house, The Kilns, known to their friends as The Midden (Old English for dung heap). What impressions do we first receive of the brothers? How does the film express briefly a little of their life “before” Joy? What do we learn during the course of the film of C. S. Lewis’s world? Apart from Joy, what other women do we “meet” in ‘Shadowlands’? How are they represented? Find out a little about Britain in the 1950s. Who was Prime Minister? When did rationing end? Why was Princess Margaret known as the “heartbreak princess”? As well as picture and library research, ask those who were alive at the time. -

Myth in CS Lewis's Perelandra

Walls 1 A Hierarchy of Love: Myth in C.S. Lewis’s Perelandra A Thesis Submitted to The Faculty of the School of Communication In Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts in English by Joseph Robert Walls May 2012 Walls 2 Liberty University School of Communication Master of Arts in English _______________________________________________________________________ Thesis Chair Date Dr. Branson Woodard, D.A. _______________________________________________________________________ First Reader Date Dr. Carl Curtis, Ph.D. _______________________________________________________________________ Second Reader Date Dr. Mary Elizabeth Davis, Ph.D. Walls 3 For Alyson Your continual encouragement, support, and empathy are invaluable to me. Walls 4 Contents Introduction......................................................................................................................................5 Chapter 1: Understanding Symbol, Myth, and Allegory in Perelandra........................................11 Chapter 2: Myth and Sacramentalism Through Character ............................................................32 Chapter 3: On Depictions of Evil...................................................................................................59 Chapter 4: Mythical Interaction with Landscape...........................................................................74 A Conclusion Transposed..............................................................................................................91 Works Cited ...................................................................................................................................94 -

Joy Davidman Lewis: Author, Editor and Collaborator

Volume 22 Number 2 Article 3 1998 Joy Davidman Lewis: Author, Editor and Collaborator Diana Pavlac Glyer Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Glyer, Diana Pavlac (1998) "Joy Davidman Lewis: Author, Editor and Collaborator," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 22 : No. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol22/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Biography of Joy Davidman Lewis and her influence on C.S. Lewis. Additional Keywords Davidman, Joy—Biography; Davidman, Joy—Criticism and interpretation; Davidman, Joy—Influence on C.S. Lewis; Davidman, Joy—Religion; Davidman, Joy. Smoke on the Mountain; Lewis, C.S.—Influence of Joy Davidman (Lewis); Lewis, C.S. -

A CS Lewis Related Cumulative Index of <I>Mythlore</I>

Volume 22 Number 2 Article 10 1998 A C.S. Lewis Related Cumulative Index of Mythlore, Issues 1-84 Glen GoodKnight Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation GoodKnight, Glen (1998) "A C.S. Lewis Related Cumulative Index of Mythlore, Issues 1-84," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 22 : No. 2 , Article 10. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol22/iss2/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Author and subject index to articles, reviews, and letters in Mythlore 1–84. Additional Keywords Lewis, C.S.—Bibliography; Mythlore—Indexes This article is available in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol22/iss2/10 MYTHLORE I s s u e 8 4 Sum m er 1998 P a g e 5 9 A C.S. -

Images of Spirit in the Fiction of Clive Staples Lewis

Volume 14 Number 2 Article 7 Winter 12-15-1987 Images of Spirit in the Fiction of Clive Staples Lewis Charlotte Spivak Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Spivak, Charlotte (1987) "Images of Spirit in the Fiction of Clive Staples Lewis," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 14 : No. 2 , Article 7. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol14/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Shows how Lewis, in his fiction, explor“ es the phenomenology of Spirit through his creation of several numinous figures who reflect medieval paradigms.” These figures reflect both medieval allegorical meanings and Jungian archetypes. Additional Keywords Lewis, C.S. Fiction—Representation of spirit; Spirit in Jung—Relation to C.S. -

Willow Creek: the Fiction of C

C.S. Lewis and the Apologetics of Story Some have claimed that C.S. Lewis drifted towards fiction the last decade of his life because he was failed as an Apologist and no longer able to keep up with the complex philosophical questions of his day. In fact, fiction was always part of Lewis’s output. He wrote, “The imaginative man in me is older than the rational man and more continually operative.” Lewis used story as one of the tools in his rhetorical tool box because he knew that some people will not listen to a coherent and reasonable presentation of the Gospel. Their rejection of the things of God is buttressed with rationalization and self-justification. Reason stands before these people’s hearts like dragon sentries preventing even the best apologetic arguments from getting through. But, Lewis believed, sometimes story can get past watchful dragons. This Network will explore Lewis’s use of story as a rhetorical and apologetical tool for the Gospel. Jerry Root is Professor of Christian Education at Wheaton College and serves as the Director of the Evangelism Initiative. Jerry is a graduate of Whittier College and Talbot Graduate School of Theology at Biola University; he received his PhD from the Open University. Jerry is the author or co-author of numerous books on C.S. Lewis, including The Surprising Imagination of C.S. Lewis: An Introduction, with Mark Neal, C.S. Lewis and a Problem of Evil: An Investigation of a Pervasive Theme, and The Soul of C.S. Lewis: A Meditative Journey through Twenty-six of His Best Loved Writings. -

Visions/Versions of the Medieval in C.S. Lewis's the Chronicles of Narnia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Boise State University - ScholarWorks VISIONS/VERSIONS OF THE MEDIEVAL IN C.S. LEWIS’S THE CHRONICLES OF NARNIA by Heather Herrick Jennings A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English, Literature Boise State University Summer 2009 © 2009 Heather Herrick Jennings ALL RIGHTS RESERVED v TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................................... vii CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 1 Lewis and the Middle Ages ............................................................................ 6 The Discarded Image ...................................................................................... 8 A Medieval Atmosphere ................................................................................. 10 CHAPTER TWO: THE HEAVENS OF NARNIA .................................................... 13 The Stars above Narnia ................................................................................... 15 The Narnian Planets ........................................................................................ 18 The Influence of the Planets ........................................................................... 19 The Moon and Fortune in Narnia ................................................................... 22 An Inside-Out Universe .................................................................................