SHADOWLANDS Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CS Lewis on Death

Volume 1 Issue 2 Article 4 January 1971 Farewell to Shadowlands: C.S. Lewis on Death Kathryn Lindskoog Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythpro Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Lindskoog, Kathryn (1971) "Farewell to Shadowlands: C.S. Lewis on Death," Mythcon Proceedings: Vol. 1 : Iss. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythpro/vol1/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythcon Proceedings by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mythcon 51: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico • Postponed to: July 30 – August 2, 2021 Abstract Examines death as portrayed in many of Lewis’s fictional and apologetic writings, and particularly in the Chronicles of Narnia. Discusses Lewis’s attitudes toward his own impending death as expressed to friends and his brother Warren. Keywords Lewis, C.S.—Attitude toward death This article is available in Mythcon Proceedings: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythpro/vol1/iss2/4 Lindskoog: Farewell to Shadowlands: C.S. Lewis on Death suooestion has been made14 that the Nine corresponded to the nine 4. JJJ 383 planets. These would be Mercury, Venus, the Earth, the Hoon, S. III 456 Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune. Pluto •as probably not 6. I 472 known to the astronomers of the Second AQe; Neptune is not 7. -

<I>Screwtape Letters</I> and <I>The Great Divorce

Volume 17 Number 1 Article 7 Fall 10-15-1990 Immortal Horrors and Everlasting Splendours: C.S. Lewis' Screwtape Letters and The Great Divorce Douglas Loney Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Loney, Douglas (1990) "Immortal Horrors and Everlasting Splendours: C.S. Lewis' Screwtape Letters and The Great Divorce," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 17 : No. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol17/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Sees Screwtape and The Great Divorce as constituting “something like a sub-genre within the Lewis canon.” Both have explicit religious intention, were written during WWII, and use a “rather informal, episodic structure.” Analyzes the different perspectives of each work, and their treatment of the themes of Body and Spirit, Time and Eternity, and Love. -

Joy Davidman Lewis: Author, Editor and Collaborator

Volume 22 Number 2 Article 3 1998 Joy Davidman Lewis: Author, Editor and Collaborator Diana Pavlac Glyer Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Glyer, Diana Pavlac (1998) "Joy Davidman Lewis: Author, Editor and Collaborator," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 22 : No. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol22/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Biography of Joy Davidman Lewis and her influence on C.S. Lewis. Additional Keywords Davidman, Joy—Biography; Davidman, Joy—Criticism and interpretation; Davidman, Joy—Influence on C.S. Lewis; Davidman, Joy—Religion; Davidman, Joy. Smoke on the Mountain; Lewis, C.S.—Influence of Joy Davidman (Lewis); Lewis, C.S. -

A CS Lewis Related Cumulative Index of <I>Mythlore</I>

Volume 22 Number 2 Article 10 1998 A C.S. Lewis Related Cumulative Index of Mythlore, Issues 1-84 Glen GoodKnight Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation GoodKnight, Glen (1998) "A C.S. Lewis Related Cumulative Index of Mythlore, Issues 1-84," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 22 : No. 2 , Article 10. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol22/iss2/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Author and subject index to articles, reviews, and letters in Mythlore 1–84. Additional Keywords Lewis, C.S.—Bibliography; Mythlore—Indexes This article is available in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol22/iss2/10 MYTHLORE I s s u e 8 4 Sum m er 1998 P a g e 5 9 A C.S. -

Shadowlands-Digital-Playbill-V4.Pdf

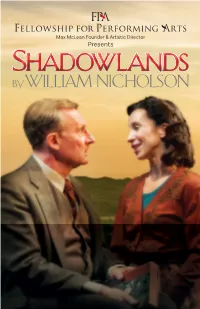

Max McLean Founder & Artistic Director Presents SHADOWLANDS by William Nicholson Max McLean, Founder & Artistic Director Presents by William Nicholson Featuring Daniel Gerroll Robin Abramson John C. Vennema Sean Gormley Dan Kremer Stephanie Cozart Daryll Heysham Eddie Ray Martin Video Editor Original Music & Sound Design Voice & Dialect Casting Director Matthew Gurren John Gromada Claudia Hill-Sparks Carol Hanzel Technical Director Production Manager Sound Editor Casting Consultant Brandon Cheney Lew Mead Daniel Gonko Judy Henderson, C.S.A. Marketing General Management Assistant Director Company Manager Southside Entertainment Aruba Productions Dan DuPraw Tara Murphy Executive Producer Ken Denison Directed by Christa Scott-Reed This production made possible by arrangement with The Agency (London) Ltd. 24 Pottery Lane, London W11 4LZ, [email protected] CAST OF CHARACTERS (in order of appearance) C.S. Lewis ...................................................................................... Daniel Gerroll Dr. Maurice Oakley/Gregg/Clerk/Doctor/Priest/Waiter ......Daryll Heysham Christopher Riley ........................................................................Sean Gormley Rev. Harry Harrington ....................................................................Dan Kremer Major Warnie Lewis ............................................................ John C. Vennema Woman/Registrar/Nurse .................................................... Stephanie Cozart Joy Davidman .........................................................................Robin -

The Grand Miracle Daily Reflections for the Season of Advent

The Grand Miracle Daily reflections for the season of advent Based on the writings of C. S. Lewis ✷ J. R. R. Tolkien ✷ Dorothy L. Sayers George MacDonald ✷ G. K. Chesterton Charles Williams ✷ Owen Barfield ✷ Joy Davidman snowy landscape. A beaming lamppost. A world where it is always winter and never Christmas. The opening scenes of C. S. Lewis’s The Lion, the Witch, Aand the Wardrobe set the stage, and readers young and old await Aslan’s return to Narnia, bringing with him the joy of Christmas. While Lewis doesn’t mention the birth of Christ specifically, he writes out of a deep sense of wonder and joy at the Incarnation as a world-transforming event: the Word becoming flesh (John 1:18). In one famous essay Lewis called it “The Grand Miracle.” You may be entering this Advent season with a sense of inadequacy. Perhaps your life is filled with great difficulty, the deep grief of loss, discouragement, finan- cial concerns, addiction, depression, or even a sense that God is far from you. The good news is that you are actually in a wonderful place to begin a meaning- ful Advent journey. For this season isn’t about what we must accomplish, but rather about what God has already done in the miracle of the Incarnation. In fact all we need to do is invite God into the authentic reality of our messy, broken, complicated Front cover by Douglas Johnson based on Edward Burne-Jones’s The Adoration (1904) lives—to be transparently present to him in the midst of our weakness. -

Course Syllabus

The Life and Thought of C.S. LEWIS TH 2XL3 / MS 2XL3 McMaster Divinity College Summer School, 2015 Instructors: Bradley K. Broadhead, Ph.D. (Cand.) [email protected] COURSE DESCRIPTION C.S. Lewis is one the most influential Christian writers of the twentieth century. Just over fifty years after his death, his theological writings and works of fiction (which are often one and the same) remain widely read and appreciated. The story of his life demonstrates in a powerful way how his encounter with Jesus Christ definitively shaped both his worldview and his actions. Together we will walk through his life and his major writings, considering his relevance for the contemporary world. COURSE OBJECTIVES Knowing To become familiar with the life and major works of Lewis To identify the major themes that emerge from Lewis’ corpus To understand the arguments for the value of contemporary parables/myths Being To engage in theological reflection on the works of Lewis To be challenged by the example of Lewis in leading a Christian life Doing To critically engage with a selected portion of Lewis’ work To evaluate Lewis’ impact on Christian and secular cultures SPECIALIZATIONS Christian Thought and History Church and Culture Christian Worldview 2 1 CLASS SCHEDULE Week 1 Tuesday, May 26 Introduction to the Course Young Lewis Lewis the Academic Lewis at War Thursday, May 28 Lewis the Atheist Lewis’ Conversion Lewis and the Inklings Week 2 Tuesday, June 2 Lewis the Popular Christian Apologist Mere Christianity The Problem of Pain Miracles Thursday, June 4 Lewis the Writer The Space Trilogy The Screwtape Letters The Great Divorce Week 3 Tuesday, June 9 The Chronicles of Narnia Until We Have Faces Thursday, June 11 Lewis, Joy, and A Grief Observed Lewis and Evangelicalism Lewis and contemporary issues 1 Please note that the instructor reserves the right to make alterations to the content and its sequence. -

The Problem of Pain Defended

Seventeen PRO: THE PROBLEM OF PAIN DEFENDED Philip Tallon In 1939, Ashley Sampson of Centenary Press invited C. S. Lewis to write on the problem of evil for the Christian Challenge series. Lewis asked if he could write anonymously, because he felt he did not live up to the hard-edged principles he would need to espouse. This would not have been first time (or the last) that Lewis published anonymously. His early poems appeared under the name “Clive Hamilton” and the memoir of his wife’s death, A Grief Observed, was attributed to “N. W. Clerk” during Lewis’s lifetime. The publisher, however, refused his request for anonymity. And so with the publication of The Problem of Pain in 1940, Lewis kick-started his role as a public philosopher and theologian. Later works in this vein would include the radio talks that were published as Mere Christianity (1952), as well as books like Miracles (1947) and The Four Loves (1960), along with numerous essays on theological and philosophical topics. But The Problem of Pain was the first, and constituted a strong entry into the public sphere. Despite some self-deprecatory remarks by Lewis at the start of the book (“If any real theologian reads these pages he will very easily see that they are the work of a layman and an amateur”), Lewis’s work is thoughtful, scriptural, steeped in the Western tradition, and ambitious in scope (Lewis, 2001c, p. vii). Within 150 pages or so, Lewis handles the origins of religion, articulates the problem of evil in various forms, deals with free will and soul making, offers an imaginative reconstruction of the origins of humanity and its fall, discusses the nature of pain in some depth, grapples with the problem of animal suffering, and theologizes about heaven and hell. -

The Immanence of Heaven in the Fiction of CS Lewis and George

Shadows that Fall: The Immanence of Heaven in the Fiction of C. S. Lewis and George MacDonald David Manley Our life is no dream; but it ought to become one, and perhaps will. (Novalis) Solids whose shadow lay Across time, here (All subterfuge dispelled) Show hard and clear. (C.S. Lewis, “Emendation for the End of Goethe’s Faust”) .S. Lewis’s impressions of heaven, including the distinctive notions ofC Shadow-lands and Sehnsucht, were shaped by George MacDonald’s fiction.1 The vision of heaven Lewis and MacDonald share is central to their stories because it constitutes the telos of their main characters; for example, the quest for heaven is fundamental to both Lewis’s The Pilgrim’s Regress and MacDonald’s “The Golden Key.” Throughout their fiction, both writers reveal a world haunted by heaven and both relate rapturous human longing after the source of earthly glimpses; both show that the highest function of art is to initiate these visions of heaven; and both describe a heaven that swallows up Earth in an all-embracing finality. The play Shadowlands is aptly named; for Lewis, the greatest earthly joys were merely intimations of another world where beauty, in Hopkins’s words, is “kept / Far with fonder a care” (“The Golden Echo” lines 44-45). He was repeatedly “surprised by Joy,” overcome with flashes ofSehnsucht during which he felt he had “tasted Heaven” (Surprised 135). For Lewis, “. heaven remembering throws / Sweet influence still on earth . .” (“The Naked Seed” 19-20). This “sweet influence” is a desire, not satisfaction; in his words, it is a “hunger better than any other fullness” (“Preface” from Pilgrim 7). -

Responding to CS Lewis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchOnline@ND University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2008 Is Pain Really God’s Megaphone? Responding to C.S. Lewis Lisa Moate University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: http://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The am terial in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Moate, L. (2008). Is Pain Really God’s Megaphone? Responding to C.S. Lewis (Honours). University of Notre Dame Australia. http://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/67 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. School of Arts and Sciences, Fremantle Is Pain Really God’s Megaphone? Responding to C.S. Lewis Bachelor of Arts (Honours) Philosophy of Lisa Moate Supervised by Dr. Richard Hamilton October 2008 2 DEDICATED TO C.S. “Jack” Lewis (1898-1963) and his beloved wife Helen Joy Davidman (1915-1960) 3 DECLARATION I declare that this Project is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary institution. ___________________________ __________________________ Name Signature ____________________ Date 4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would first like to thank my supervisor, Dr. -

An Introduction to C. S. Lewis

An Introduction to C. S. Lewis Clive Staples Lewis—C. S. Lewis to many readers—was born in Belfast, Ireland, on November 29, 1898. His parents were Albert James Lewis, a solicitor, and Florence Augusta Lewis. Lewis had one brother, Warren Hamilton Lewis, with whom he remained close for all of his life. Lewis read widely as a child, but dearly enjoyed stories about animals and nature, a theme which resurfaced in his later work The Chronicles of Narnia. Lewis and his brother Warren even created an imaginary world called Boxen in which animals lived and talked together. Coupled with Lewis’ love of creating worlds filled with anthropomorphic animals and lively natural settings was his love for ancient literature, including the epic sagas of Iceland, Norse mythology, and Greek and Medieval literature. Readers familiar with his work will recognize how these these genres and themes influenced the trajectory of his life’s work. In his early years of education, Lewis attended several private preparatory schools in Britain, including Wynyard School in Hertfordshire (1908), Campbell College in Belfast (1910), and Cherbourg House at Malvern, Worcestershire (1911). Due to poor health, though, he never remained at these schools for long. It was during his time in Worcestershire that Lewis pronounced himself an atheist, a belief he held onto until 1929 when he became a theist and then a Christian. In December 1916, Lewis received a scholarship to study at University College, Oxford. His life of academic study took a tremendous turn, however, for in 1917 Lewis enlisted in the British Army. After training, Lewis attained the rank of Second Lieutenant with the Third Battalion of the Somerset Light Infantry. -

C. S. Lewis on Gender Ann Loades Introduction Riess a Well a Continuing to Work on Farms

C. S. Lewis on Gender Ann Loades Introduction riess a well a continuing to work on farms. They worked in trans- port t and a the front, as well as at home as nurses and ambulance Cautious though one must be in thinking that one can entirely drivers,n i addition to all the other tasks they performed. It was understand someone in terms of their circumstances, C. S. Lewis not until February 6, 1918, that some women (those over thirty (CSL) virtually invites us to pay attention to his by the publica- years old, householders or wives thereof, occupiers of property tionfs o hi Surprised by Joy (1955).s Thi text, which we can now wortht a least five pounds per year, and university graduates)5 es - reads a a classic of “textual male intimacy” in religion,1 s fi one o cured the vote. Men simply had to be nineteen years or older and those resources particularly important when we try to grasp what ableo t supply an address. The age restriction for women dropped CSL meant and could not mean by “masculinity,” as will become to twenty-one in 1928. The time had come when women, married clear in the last part of this article. In addition, we need to attend or not, could no longer be regarded as legal nonentities, deprived to a whole range of his publications when we attempt to assess his of adequate education and economic resources, though much re- understanding of “femininity” and its relation to “masculinity.” mainedoe t b achieved in the twentieth century.