<I>Screwtape Letters</I> and <I>The Great Divorce

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CS Lewis on Death

Volume 1 Issue 2 Article 4 January 1971 Farewell to Shadowlands: C.S. Lewis on Death Kathryn Lindskoog Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythpro Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Lindskoog, Kathryn (1971) "Farewell to Shadowlands: C.S. Lewis on Death," Mythcon Proceedings: Vol. 1 : Iss. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythpro/vol1/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythcon Proceedings by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mythcon 51: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico • Postponed to: July 30 – August 2, 2021 Abstract Examines death as portrayed in many of Lewis’s fictional and apologetic writings, and particularly in the Chronicles of Narnia. Discusses Lewis’s attitudes toward his own impending death as expressed to friends and his brother Warren. Keywords Lewis, C.S.—Attitude toward death This article is available in Mythcon Proceedings: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythpro/vol1/iss2/4 Lindskoog: Farewell to Shadowlands: C.S. Lewis on Death suooestion has been made14 that the Nine corresponded to the nine 4. JJJ 383 planets. These would be Mercury, Venus, the Earth, the Hoon, S. III 456 Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune. Pluto •as probably not 6. I 472 known to the astronomers of the Second AQe; Neptune is not 7. -

SHADOWLANDS Introduction

SHADOWLANDS Introduction ‘Shadowlands’ tells of the extraordinary love between C. S. Lewis, the famous writer and Christian academic and Joy Gresham, an American poet who came to know him first through his writing. She was to die shortly after their marriage. ‘Shadowlands’ was first a television and then a stage play and is now a film starring Anthony Hopkins and Debra Winger. This guide is for use before and after a viewing of Richard Attenborough’s film. It seeks to expand for class work the themes of love and bereavement, the risks of emotional involvement and the challenge to all faiths of pain and tragedy as well as discussing the way film tackles these difficult subjects. JACK AND JOY Olive Staples Lewis - known always as Jack - was born in 1898 in Belfast three years after the Lewis’s first son, Warren or “Warnie”. The brothers were very close, and spent much of their adult bachelor life living together near Oxford in a ramshackle house, The Kilns, known to their friends as The Midden (Old English for dung heap). What impressions do we first receive of the brothers? How does the film express briefly a little of their life “before” Joy? What do we learn during the course of the film of C. S. Lewis’s world? Apart from Joy, what other women do we “meet” in ‘Shadowlands’? How are they represented? Find out a little about Britain in the 1950s. Who was Prime Minister? When did rationing end? Why was Princess Margaret known as the “heartbreak princess”? As well as picture and library research, ask those who were alive at the time. -

Myth in CS Lewis's Perelandra

Walls 1 A Hierarchy of Love: Myth in C.S. Lewis’s Perelandra A Thesis Submitted to The Faculty of the School of Communication In Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts in English by Joseph Robert Walls May 2012 Walls 2 Liberty University School of Communication Master of Arts in English _______________________________________________________________________ Thesis Chair Date Dr. Branson Woodard, D.A. _______________________________________________________________________ First Reader Date Dr. Carl Curtis, Ph.D. _______________________________________________________________________ Second Reader Date Dr. Mary Elizabeth Davis, Ph.D. Walls 3 For Alyson Your continual encouragement, support, and empathy are invaluable to me. Walls 4 Contents Introduction......................................................................................................................................5 Chapter 1: Understanding Symbol, Myth, and Allegory in Perelandra........................................11 Chapter 2: Myth and Sacramentalism Through Character ............................................................32 Chapter 3: On Depictions of Evil...................................................................................................59 Chapter 4: Mythical Interaction with Landscape...........................................................................74 A Conclusion Transposed..............................................................................................................91 Works Cited ...................................................................................................................................94 -

Joy Davidman Lewis: Author, Editor and Collaborator

Volume 22 Number 2 Article 3 1998 Joy Davidman Lewis: Author, Editor and Collaborator Diana Pavlac Glyer Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Glyer, Diana Pavlac (1998) "Joy Davidman Lewis: Author, Editor and Collaborator," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 22 : No. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol22/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Biography of Joy Davidman Lewis and her influence on C.S. Lewis. Additional Keywords Davidman, Joy—Biography; Davidman, Joy—Criticism and interpretation; Davidman, Joy—Influence on C.S. Lewis; Davidman, Joy—Religion; Davidman, Joy. Smoke on the Mountain; Lewis, C.S.—Influence of Joy Davidman (Lewis); Lewis, C.S. -

C.S. Lewis' <I>The Great Divorce</I> and the Medieval Dream Vision

Volume 10 Number 2 Article 12 1983 C.S. Lewis' The Great Divorce and the Medieval Dream Vision Robert Boeing Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Boeing, Robert (1983) "C.S. Lewis' The Great Divorce and the Medieval Dream Vision," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 10 : No. 2 , Article 12. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol10/iss2/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Discusses the genre of the medieval dream vision, with summaries of some of the best known (and their precursors). Analyzes The Great Divorce as “a Medieval Dream Vision in which [Lewis] redirects the concerns of the entire genre.” Additional Keywords Lewis, C.S. -

Shadowlands-Digital-Playbill-V4.Pdf

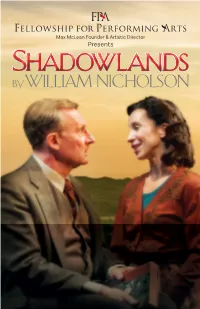

Max McLean Founder & Artistic Director Presents SHADOWLANDS by William Nicholson Max McLean, Founder & Artistic Director Presents by William Nicholson Featuring Daniel Gerroll Robin Abramson John C. Vennema Sean Gormley Dan Kremer Stephanie Cozart Daryll Heysham Eddie Ray Martin Video Editor Original Music & Sound Design Voice & Dialect Casting Director Matthew Gurren John Gromada Claudia Hill-Sparks Carol Hanzel Technical Director Production Manager Sound Editor Casting Consultant Brandon Cheney Lew Mead Daniel Gonko Judy Henderson, C.S.A. Marketing General Management Assistant Director Company Manager Southside Entertainment Aruba Productions Dan DuPraw Tara Murphy Executive Producer Ken Denison Directed by Christa Scott-Reed This production made possible by arrangement with The Agency (London) Ltd. 24 Pottery Lane, London W11 4LZ, [email protected] CAST OF CHARACTERS (in order of appearance) C.S. Lewis ...................................................................................... Daniel Gerroll Dr. Maurice Oakley/Gregg/Clerk/Doctor/Priest/Waiter ......Daryll Heysham Christopher Riley ........................................................................Sean Gormley Rev. Harry Harrington ....................................................................Dan Kremer Major Warnie Lewis ............................................................ John C. Vennema Woman/Registrar/Nurse .................................................... Stephanie Cozart Joy Davidman .........................................................................Robin -

The Immanence of Heaven in the Fiction of CS Lewis and George

Shadows that Fall: The Immanence of Heaven in the Fiction of C. S. Lewis and George MacDonald David Manley Our life is no dream; but it ought to become one, and perhaps will. (Novalis) Solids whose shadow lay Across time, here (All subterfuge dispelled) Show hard and clear. (C.S. Lewis, “Emendation for the End of Goethe’s Faust”) .S. Lewis’s impressions of heaven, including the distinctive notions ofC Shadow-lands and Sehnsucht, were shaped by George MacDonald’s fiction.1 The vision of heaven Lewis and MacDonald share is central to their stories because it constitutes the telos of their main characters; for example, the quest for heaven is fundamental to both Lewis’s The Pilgrim’s Regress and MacDonald’s “The Golden Key.” Throughout their fiction, both writers reveal a world haunted by heaven and both relate rapturous human longing after the source of earthly glimpses; both show that the highest function of art is to initiate these visions of heaven; and both describe a heaven that swallows up Earth in an all-embracing finality. The play Shadowlands is aptly named; for Lewis, the greatest earthly joys were merely intimations of another world where beauty, in Hopkins’s words, is “kept / Far with fonder a care” (“The Golden Echo” lines 44-45). He was repeatedly “surprised by Joy,” overcome with flashes ofSehnsucht during which he felt he had “tasted Heaven” (Surprised 135). For Lewis, “. heaven remembering throws / Sweet influence still on earth . .” (“The Naked Seed” 19-20). This “sweet influence” is a desire, not satisfaction; in his words, it is a “hunger better than any other fullness” (“Preface” from Pilgrim 7). -

Shadowlands Script

Shadowlands, A Summary of the Story in the Movie Pre-movie notes: comment on The Magician’s Nephew, Fred Paxford, and the Common Room. 90-minute version starts with High Table, Jack says, “Why am I so afraid? … shadows. Real life hasn’t begun.” 73-minute version starts with a BBC address by Lewis. Radio Voice: “The time is just coming up to ten minutes to 3. We are now broadcasting the sixth in a series of eight talks by the writer C. S. Lewis, best known for his imaginative fables The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe and The Screwtape Letters. This afternoon his theme is Christian marriage.” Jack: “I must begin by making it plain that I have never been married myself. However, the Christian idea of marriage is not based on the experience of individual men and women, but on the teaching of Christ, that is, that marriage is for life.” [laughter] Christopher: “And now the honorable professor plain Jack Lewis will make another very complicated question very simple. This week infanticide. Infanticide is a long word, isn’t it? Let me put it to you in the bluff common man’s language that has made me so popular among bluff common men.” Jack: “I don’t believe you heard a word of it.” Christopher: “A noble address, Jack. Judiciously navigated.” Jack: “Shouldn’t I have said that I’ve not been married?” Clergyman: “Not at all. The personal touch.” Jack: “Anyway I don’t see that it makes any difference. We don’t expect those who teach us sexual morality to be practicing fornicators.” Fellow: “I shouldn’t play that card too often.” Jack: Fellow: “The expert on marriage who’s never been married. -

'The Full Treatment': C. S. Lewis on Repentance, the Process Of

The Dulia et Latria Journal, Vol. 3 (2010) 21 The “Full Treatment”: C. S. Lewis on Repentance, the Process of Becoming a “New-Made Man” By Chris Garrett Oklahoma City University (documentation in author’s style) The ultimate spiritual goal of most Christians is to go to heaven and live with God after death. According the Christian apologist C. S. Lewis, God desires to prepare us for eternal life by making us into new creatures. Having set the standard of absolute perfection before us and knowing that humanity falls short of that standard, God has prepared a way for man to become perfected. Through the atonement of Jesus Christ and the process of repentance man can be forgiven of sins and become glorified, immortal creatures. This essay explores and examines Lewis’s ideas on this core Christian principle of repentance. Lewis defines repentance as a gradual process of transformation that will not be completed during mortality (Mere Christianity 159-161). It is a process of surrender, in essence killing a part of yourself (44-45). By that Lewis is referring to his belief that man is an amphibian—“half animal and half spirit” (Screwtape Letters 36). When man surrenders to God, he attempts to forsake the natural and carnal man (the animal part) in favor of following his spiritual self. 22 Chris Garrett, “Lewis on Repentance” An important aspect of repentance is realizing you are on the wrong track and then getting back on the right road (Mere Christianity 44). Lewis describes repentance in terms of progress: We all want progress. -

Dante's Divine Comedy in the Novels of CS Lewis

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Faculty Publications - Department of English Department of English 6-2016 Reflecting the Eternal: Dante's Divine Comedy in the Novels of C. S. Lewis (Book Review) Gary L. Tandy George Fox University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/eng_fac Part of the Christianity Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Tandy, Gary L., "Reflecting the Eternal: Dante's Divine Comedy in the Novels of C. S. Lewis (Book Review)" (2016). Faculty Publications - Department of English. 57. http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/eng_fac/57 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications - Department of English by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reflecting the Eternal: Dante’s Divine Comedy in the Novels of c. 5. Lewis■ By Marsha Daigle-Williamson, Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2015. ISBN 978-1- 61970-665-1. Pp. 330. $16.95. That c. s. lewis was a great admirer of Dante’s poetry, specifically his Divine Comedy, will come as no surprise to readers of Lewis’s fiction, literary criticism, and letters. At his first reading of the poem as a 20-year-old, Lewis stated that the Paradiso reaches ”heights of poetry you get nowhere else” (Letter to Arthur Greeves, October 13, 1918), and 10 years later he thought ”Dante’s poetry, on the whole, the greatest of all the poetry” he had read (Studies in Medieval and Renaissance Literature, 76). -

The Great Divorce: C.S. Lewis – Falling Between the Cracks

Douglas Ayling THEO 656A: Augustine: City of God The Great Divorce: C.S. Lewis – Falling between the cracks Unless otherwise stated, all page numbers refer to: C.S. Lewis, The Great Divorce (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1946) The structure of this paper will be as follows. First a brief synopsis of the plot of The Great Divorce is provided. I then delineate aspects of the theological position which Clive Staples “Jack” Lewis appears to stake out in this work of fiction. Discussion follows of the implications, some possible difficulties and internal inconsistencies. Then, in the context of Saint Augustine of Hippo’s City of God, I do my best to get the texts talking to each other. Again, the caveat: my competence to implement the above is limited. I entreat your patience where necessary. 1. Plot synopsis: The Great Divorce In this relatively short allegorical novel, C.S. Lewis’ first person narrator journeys by bus upwards from a dreary suburban purgatory / hell to another realm where above and beyond a pastoral idyll, an alpine divine resides. We see, first on the bus, later in heaven, a series of undesirable characters. Their faults are usually obvious and serve to provide illustrations of why they will get back onto the bus and go back to purgatory / hell. The welcoming party consists of nominated counterparts who have interrupted their journey “further and further into the mountains” (p.69). In most of these cases they knew the arrival while they were alive and the pilgrim is required to walk with them, receiving assistance on the journey towards God. -

Production Begins Next Month for New C.S. Lewis Motion Picture Production Begins Next Month for New C.S

HOME > C.S. LEWIS > C.S. LEWIS MOVIES > Production Begins Next Month for New C.S. Lewis Motion Picture Production Begins Next Month for New C.S. Lewis Motion Picture August 30, 2020 • David Sutton • C.S. Lewis Movies Tomorrow Max McLean of Fellowship for Performing Arts will fly to the United Kingdom where he will begin shooting on location for the motion picture film adaptation of C.S. Lewis The Most Reluctant Convert. Fellowship for Performing Arts has amazed audiences with top notch C.S. Lewis stage productions The Screwtape Letters, The Great Divorce, Shadowlands, and C.S. Lewis The Most Reluctant Convert. The material that this movie is based upon is Max McLean’s one man stage play that chronicles the Narnia author’s journey from atheism to Christianity (NarniaFans.com 4 Shield Review). Although a filmed from the stage version of this production is already available on DVD, the new movie version will be entirely different with a full cast shoot- ing at historic locations from C.S. Lewis’s life. “The difference about this play is it’s going to be on location all over Oxford. We have full access to Maudlin College, The Kilns, the church, [and] various other places that are mentioned in the play. Instead of it being a one person show, it’s going to be a multi-actor show. I’ll play the older Lewis, we’ll have a boy Lewis, a young Lewis in his 20’s, cast his mother, his father, Tolkien, Barfield, Kirk, among others, and that is going to begin shortly.” – Max McLean In March 2020 the entire world of Fellowship for Performing Arts came to a complete standstill.