The Study of Transformation Through the Life and Literature of Cs Lewis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mercy Vs. Law and Justice: a False Dichotomy”

“Mercy vs. Law and Justice: A False Dichotomy” Speaker Series for St. Catherine Laboure Parish Glenview, Illinois March 12, 2017 † Most Reverend Thomas John Paprocki Bishop of Springfield in Illinois My dear brothers and sisters in Christ: It is good to be back with you here at St. Catherine Laboure Parish, where I served as deacon from the summer of 1977 until my ordination as a priest in May of 1978. It is hard to believe that forty years have passed since then, but this parish and many of the parishioners still have a special place in my heart. The topic of my presentation is, “Mercy vs. Law and Justice: A False Dichotomy.” Specifically, I will address the questions: how can God be just and merciful at the same time? Can there be mercy without judgment? I will describe how a well-formed conscience enables us to experience God’s mercy. I will also look at how moral law, canon law or church law and civil law bind us and how they free us. 2 By way of introducing these themes, I start by recalling one of my favorite movies, “Shadowlands,” the 1993 film about the British author and Oxford University scholar C.S. Lewis, starring one of my favorite actors, Anthony Hopkins, who played the part of Lewis. After I saw that movie for the first time in the theater, I rented the video and did something that I had never done before and have never done since: I watched the video in my living room with a note pad and jotted down quotes from the profound theological insights that were being spoken by the character of Lewis in the movie, which was based on his real life experiences dealing with the terminal illness of his wife Joy, who was dying of cancer. -

<I>Screwtape Letters</I> and <I>The Great Divorce

Volume 17 Number 1 Article 7 Fall 10-15-1990 Immortal Horrors and Everlasting Splendours: C.S. Lewis' Screwtape Letters and The Great Divorce Douglas Loney Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Loney, Douglas (1990) "Immortal Horrors and Everlasting Splendours: C.S. Lewis' Screwtape Letters and The Great Divorce," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 17 : No. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol17/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Sees Screwtape and The Great Divorce as constituting “something like a sub-genre within the Lewis canon.” Both have explicit religious intention, were written during WWII, and use a “rather informal, episodic structure.” Analyzes the different perspectives of each work, and their treatment of the themes of Body and Spirit, Time and Eternity, and Love. -

Imaginative Rationality: Philosophical Themes in C.S

Loyola Marymount University Fall, 2013 First Year Seminar Imaginative Rationality: Philosophical Themes in C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, and Their Intellectual Circle Course Number: 44950, FFYS 1000, section 72 Course Schedule: Tuesdays and Thursdays, 3:004:15 PM Course Location: Pereira 207 Instructor: Dr. Thomas Ward University Hall 3618 [email protected] (310)-338-4287 (phone) (310)-338-5997 (fax) Office Hours: Tuesdays and Thursdays, 9:1510:15 AM and 2:00-3:00 PM Writing Instructor: Mr. Joshua Kulmac Butler [email protected] Course Description: This course will introduce you to the philosophical thought of Lewis, Tolkien, some other members of their circle, and some of their intellectual influences. We will explore traditional philosophical themes through the fiction and non-fiction of these and other authors. These themes include: the existence of God, the problem of evil, human nature, moral knowledge, and the meaningfulness of figurative language. Since we will be examining some of these philosophical issues through literature, one major question that we will ask throughout the course is this: To what extent can imaginative discourse effectively communicate truth? Required Texts: C.S. Lewis, The Problem of Pain, ISBN: 0060652969 C.S. Lewis, Perelandra, ISBN: 074323491X C.S. Lewis, The Abolition of Man, ISBN: 0060652942 C.S. Lewis, That Hideous Strength, ISBN: 0743234928 Charles Williams, Descent into Hell, ISBN: 0802812201 J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings, ISBN: 9780544003415 and lots of other texts that will be available as .pdf downloads on Blackboard Please make every effort to buy precisely these editions. -

Surrounded! “C. S. LEWIS: SURPRISED by JOY!”

June 21, 2015 Surrounded! “C. S. LEWIS: SURPRISED BY JOY!” Rev. Gary Haller First United Methodist Church Birmingham, Michigan John 16:19-22 Jesus knew that they wanted to ask him, so he said to them, “Are you discussing among yourselves what I meant when I said, ‘A little while, and you will no longer see me, and again a little while, and you will see me’? Very truly, I tell you, you will weep and mourn, but the world will rejoice; you will have pain, but your pain will turn into joy. When a woman is in labor, she has pain, because her hour has come. But when her child is born, she no longer remembers the anguish because of the joy of having brought a human being into the world. So you have pain now; but I will see you again, and your hearts will rejoice, and no one will take your joy from you.” Matthew 13:44 “The kingdom of heaven is like treasure hidden in a field, which someone found and hid; then in his joy he goes and sells all that he has and buys that field.” “Once there were four children whose names were Peter, Susan, Edmund and Lucy. This story is about something that happened to them when they were sent away from London during the war because of the air-raids. They were sent to the house of an old Professor who lived in the heart of the country, ten miles from the nearest railway station and two miles from the nearest post office.” Peter, Susan, Edmund and Lucy soon realize that they have a lot of freedom due to the lack of supervision and decide to play a game of hide and seek in the house. -

The Face of the Materialist Magician: Lewis, Tolkien, and the Art of Crossing Perilous Streets

Volume 35 Number 1 Article 2 10-15-2016 The Face of the Materialist Magician: Lewis, Tolkien, and the Art of Crossing Perilous Streets Robert Boenig Texas A&M University in College Station, TX Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Boenig, Robert (2016) "The Face of the Materialist Magician: Lewis, Tolkien, and the Art of Crossing Perilous Streets," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 35 : No. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol35/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Plenary address, Mythcon 47. Concerns the character of the “Materialist Magician” (Screwtape’s term) in Tolkien and Lewis—the Janus-like figure who looks backward to magic and forward to scientism, without the moral core to reconcile his liminality. -

Utopia in Deep Heaven: Thomas More and C.S. Lewis's Cosmic Trilogy

Volume 35 Number 2 Article 8 4-15-2017 Utopia in Deep Heaven: Thomas More and C.S. Lewis's Cosmic Trilogy Benjamin C. Parker Northern Illinois University in De Kalb, IL Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Parker, Benjamin C. (2017) "Utopia in Deep Heaven: Thomas More and C.S. Lewis's Cosmic Trilogy," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 35 : No. 2 , Article 8. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol35/iss2/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Teases out parallels to Thomas More’s Utopia the solar system of Lewis’s Cosmic Trilogy, to show how Lewis’s scholarly engagement with this text informs his depictions of Malacandra, Perelandra, and the smaller world of the N.I.C.E. -

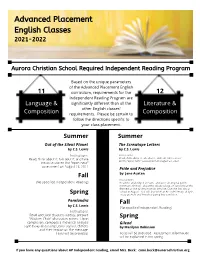

Required Independent Reading Program

Advanced Placement English Classes 2021-2022 Aurora Christian School Required Independent Reading Program Based on the unique parameters of the Advanced Placement English 11 curriculum, requirements for the 12 Independent Reading Program are Language & significantly different than all the Literature & other English classes' Composition requirements. Please be certain to Composition follow the directions specific to your class placement. Summer Summer Out of the Silent Planet The Screwtape Letters by C.S. Lewis by C.S. Lewis Instructions: Instructions: Read, think about it, talk abut it, and take Read, think about it, talk abut it, and take notes to use on the "open-note" assessment on August 23, 2021 notes to use on the "open-note" assessment on August 23, 2021 Pride and Prejudice Fall by Jane Austen Instructions: (No specified Independent Reading) Read the unabridged version, and write an original poem - minimum 30 lines - about the ideals, values, or concerns of the Bennets or the society in which they live. Due the first day of school in August. You will also write an AP style literary analysis Spring essay on Pride and Prejudice during first semester. Perelandra Fall by C.S. Lewis (No specified Independent Reading) Instructions: Read specified chapters weekly, prepare "Wisdom Chair" discussion points. Upon Spring completion, compose a rhetorical analysis Gilead style essay discussing Lewis' stylistic choices by Marilynn Robinson and their impact on the message. Texts will be provided. Texts will be provided. Assessment information will be explained in the spring. If you have any questions about AP Independent reading, email Mrs. Beck: [email protected].. -

SHADOWLANDS Introduction

SHADOWLANDS Introduction ‘Shadowlands’ tells of the extraordinary love between C. S. Lewis, the famous writer and Christian academic and Joy Gresham, an American poet who came to know him first through his writing. She was to die shortly after their marriage. ‘Shadowlands’ was first a television and then a stage play and is now a film starring Anthony Hopkins and Debra Winger. This guide is for use before and after a viewing of Richard Attenborough’s film. It seeks to expand for class work the themes of love and bereavement, the risks of emotional involvement and the challenge to all faiths of pain and tragedy as well as discussing the way film tackles these difficult subjects. JACK AND JOY Olive Staples Lewis - known always as Jack - was born in 1898 in Belfast three years after the Lewis’s first son, Warren or “Warnie”. The brothers were very close, and spent much of their adult bachelor life living together near Oxford in a ramshackle house, The Kilns, known to their friends as The Midden (Old English for dung heap). What impressions do we first receive of the brothers? How does the film express briefly a little of their life “before” Joy? What do we learn during the course of the film of C. S. Lewis’s world? Apart from Joy, what other women do we “meet” in ‘Shadowlands’? How are they represented? Find out a little about Britain in the 1950s. Who was Prime Minister? When did rationing end? Why was Princess Margaret known as the “heartbreak princess”? As well as picture and library research, ask those who were alive at the time. -

The Complete CS Lewis Signature Classics

THE COMPLETE C. S. LEWIS SIGNATURE CLASSICS: BOXED SET PDF, EPUB, EBOOK C. S. Lewis | 1584 pages | 11 Oct 2012 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007500192 | English | London, United Kingdom The Complete C. S. Lewis Signature Classics: Boxed Set PDF Book Chronicles of Narnia: The Chronicles of Narnia Box Set [] The seven chronicles of Narnia are brought together in this beautifully presented slipcase. From 'The Problem of Pain' - a wise and compassionate exploration of suffering - to the darkly satirical 'The Screwtape Letters', Lewis is unrivalled in his ability to disentangle the questions of life. Date of Birth: November 29, Best Selling in Nonfiction See all. By: C. View all copies of this ISBN edition:. New Paperback Quantity available: 3. And I understood what he was trying to portray in the "Weston" character from his fiction novel, Out of the Silent Planet a little better now. Titles in This Set. View Product. He does not make absolutely clear the centrality of the gospel and belief in Jesus Christ as the only way to eternal life. Jun 28, Robert rated it it was amazing Shelves: art , non-fiction. Hopefully not many. Seller assumes all responsibility for this listing. Search by title, catalog stock , author, isbn, etc. Seller Inventory V Read this as Lewis would have The preface is the most important part of the book, in this case, so that you understand that the wisdom and lessons of this story are found in the conversations held within. Adam gave me the boxed set ok, I cheated and it was on CD but I had read all of these years ago. -

Ryan Hudson Honors Thesis-May 2021

! ! ! ! ! ! "#$%&"'%! ()*+,-,.)+,/0!,/!'*1)+,2/! &3)/!45!67892/! :,*1-+2*;!:*5!<,-=)1>!?2>13! ! ! @A1/!#)*B,1>8!=)9!2B+1/!C11/!.*191/+18!)9!)/!,/+1>>1-+7)>!2..2/1/+!2B!'5!$5! D1A,9E!C7+!+=,9!B),>9!+2!)--27/+!B2*!+=1!-2F.>1F1/+)*3!+=1F19!+=)+!)..1)*!,/!+=1!A2*G9!2B! +=191!+A2!B*,1/89E!.)*+,-7>)*>3!+=1F19!*10)*8,/0!=7F)/,+3!,/!+=1!H1A!'*1)+,2/5!@A1/! #)*B,1>8!-2/9+*7-+9!)/!)--27/+!2B!=7F)/!=,9+2*3!,/!+1*F9!2B!=7F)/,+3I9!*1>)+,2/9=,.!+2! /)+7*1E!+*)-,/0!.)++1*/9!)/8!+=1F19!+=)+!>1)8!7.!+2!)/8!+=1/!0*2A!27+!B*2F!+=1!J/-)*/)+,2/! 2B!'=*,9+5!@/!+=1!2+=1*!=)/8E!'5!$5!D1A,9!A*,+19!2B+1/!)C27+!+=1!H1A!'*1)+,2/E!C7+!=1! -2/9,9+1/+>3!1F.=)9,K19!+=1!F39+1*3!2B!A=)+!,9!+2!-2F15!#3!)..>3,/0!#)*B,1>8I9!,81)!2B! +=1!1L2>7+,2/!2B!-2/9-,279/199!+2!+=1!M719+,2/9!D1A,9!*),919!*10)*8,/0!+=1!H1A!'*1)+,2/E! +=,9!+=19,9!),F9!+2!81F2/9+*)+1!+=1!*,-=!+=1F19!+=)+!+=1!A2*G9!2B!+=191!+A2!A*,+1*9!8*)A! 27+!B*2F!2/1!)/2+=1*5!%2!+=,9!1/8E!+=1!+=19,9!A,>>!C10,/!A,+=!)/!1N.>)/)+,2/!2B!#)*B,1>8I9! !"#$%&'()*'+,,*"-"%.*/E!B2>>2A18!C3!)/!)..>,-)+,2/!2B!#)*B,1>8I9!7/81*9+)/8,/0!+2! D1A,9I9!+*1)+F1/+!2B!+=1!H1A!67F)/,+3!,/!0*-*'1)-$/($"%$(2E!,/+1*.*1+18!)--2*8,/0!+2! D1A,9I9!2+=1*!A2*G9!C2+=!,/!B,-+,2/!O3)*'1)-4%$.5*/'46'7"-%$"!)/8!3)"('8$9*4:/' !(-*%&()P!)/8!,/!/2/B,-+,2/!O0*-*'1)-$/($"%$(2')/8!0$-".5*/P5!%=,9!)..>,-)+,2/!>1)89!+2!)/! 1N.)/9,L1!)/8!,F)0,/)+,L1!7/81*9+)/8,/0!2B!+=1!H1A!'*1)+,2/!)9!C2+=!)!.*191/+!)/8!)! B7+7*1!*1)>,+35!! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! "((&@QR:!#S!:J&R'%@&!@?!6@H@&$!%6R$J$;! ! ! ! !!!!!!TTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT! -

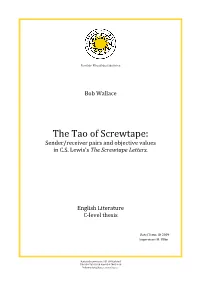

The Tao of Screwtape: Sender/Receiver Pairs and Objective Values in C.S

Estetisk- Filosofiska fakulteten Bob Wallace The Tao of Screwtape: Sender/receiver pairs and objective values in C.S. Lewis’s The Screwtape Letters. English Literature C-level thesis Date/Term: Ht 2009 Supervisor: M. Ullén Karlstads universitet 651 88 Karlstad Tfn 054-700 10 00 Fax 054-700 14 60 [email protected] www.kau.se Title: The Tao of Screwtape: An examination of sender/receiver pairs for awareness of and relationship to a doctrine of objective values in C.S. Lewis’s The Screwtape Letters. Author: Bob Wallace Eng C, HT 2009 Pages: 15 Abstract: The purpose of this essay is to identify the various sender/receiver pairs from C.S. Lewis’s novel The Screwtape Letters and, once identified, to examine these pairs within the context of the concept of a doctrine of universal values which is expressed in Lewis’s The Abolition of Man. For the sake of clarity and simplicity the essay begins with a definition of terms and concepts that will be used throughout, including basic terms used when discussing a communicative act: sender, receiver and message. I then explain the essays central concept which is taken from another one of Lewis’s works The Abolition of Man regarding a doctrine of objective value. The idea that a set of universal values exists is often central to secular writing and C.S Lewis, a Christian apologist, makes it clear that he believes that there exists an ethical way of living that is common to all men, Christian and non- Christian alike. He dubs this set of basic morals the Tao. -

Myth in CS Lewis's Perelandra

Walls 1 A Hierarchy of Love: Myth in C.S. Lewis’s Perelandra A Thesis Submitted to The Faculty of the School of Communication In Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts in English by Joseph Robert Walls May 2012 Walls 2 Liberty University School of Communication Master of Arts in English _______________________________________________________________________ Thesis Chair Date Dr. Branson Woodard, D.A. _______________________________________________________________________ First Reader Date Dr. Carl Curtis, Ph.D. _______________________________________________________________________ Second Reader Date Dr. Mary Elizabeth Davis, Ph.D. Walls 3 For Alyson Your continual encouragement, support, and empathy are invaluable to me. Walls 4 Contents Introduction......................................................................................................................................5 Chapter 1: Understanding Symbol, Myth, and Allegory in Perelandra........................................11 Chapter 2: Myth and Sacramentalism Through Character ............................................................32 Chapter 3: On Depictions of Evil...................................................................................................59 Chapter 4: Mythical Interaction with Landscape...........................................................................74 A Conclusion Transposed..............................................................................................................91 Works Cited ...................................................................................................................................94