Anthropological Science 110(2), 165-177, 2002 Preliminary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

37 Correspondence Analysis of Indonesian Retail

Indonesian Journal of Business and Entrepreneurship, Vol. 4 No. 1, January 2018 Permalink/DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17358/IJBE.4.1.37 Accredited by Ministry of Available online at http://journal.ipb.ac.id/index.php/ijbe RTHE Number 32a/E/KPT/2017 CORRESPONDENCE ANALYSIS OF INDONESIAN RETAIL BANKING PERSONAL LOANS TOP UP Andrie Agustino*)1, Ujang Sumarwan**), and Bagus Sartono***) *) Bank Mandiri Jl. Jend. Sudirman Kav. 54-55, South Jakarta, 12190 **) Department of Family and Consumer Sciences, Faculty of Human Ecology, Bogor Agricultural University IPB Darmaga Campus, Bogor 16680 ***) Department of Statistics, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Science, Bogor Agricultural University Jl. Meranti Wing 22 level 4-5, Kampus IPB Darmaga, Bogor 16680 Abstract: Customer experience can be developed through good database management, and this is an important thing to do in the era of tough retail banking competition especially in the personal loan market competition. Through good database management, banks can understand the transaction pattern and customer behavior in each bank service’s contact point. This research aimed at identifying the personal loans correspondence between socioeconomic variables and top up transaction by using the secondary data from one of Indonesian retail banking. The research method used the correspondence analysis and regression. The result of the research showed that the socioeconomic factors that influenced the debtors to top up personal loans at the confidence level of 5% (0.05) included Age, Marital Status, Dependent Number, Living Status, Education, Region, Job Type, Work Length, Salary, Debt Burdened Ratio (DBR), Credit Tenure, and Credit Limit, and only Gender had no effect on personal loan top up. -

Homo Erectus Foodways

Homo Erectus Foodways ENVIRONMENT 3 RAINFOREST 4 OUT OF AFRICA 4 DIFFERENT ENVIRONMENTS 5 MORPHOLOGY & LOCOMOTION 7 Did Homo Erectus still sleep in the trees? 11 CAPTURE 14 TEETH AND JAW 15 C3/C4 ANALYSIS 16 HOARDING 21 ANIMAL FOODS 21 HUNTING AND SCAVENGING 22 HUNTING METHODS 29 SEAFOOD 35 SUMMARY 37 PROCESSING & INGESTION 38 TOOLS 38 THROWN TOOLS 41 BUTCHERY 43 PLANT TOOLS 44 DENTAL ADAPTATIONS 44 MICROWEAR 46 COOKING 51 FIRE 53 COOKING SUMMARY 60 COOKED VS RAW CONSUMPTION 60 FERMENTED FOODS 61 COOKING TECHNOLOGIES 61 COOKING STARCHES 62 COOKING PROTEINS 64 COOKING FATS 67 VITAMINS AND MINERALS 69 PLANT DEFENSES 70 DIGESTION 70 METABOLISM 73 EXPENSIVE TISSUE HYPOTHESIS 74 NUTRIENTS FOR ENCEPHALIZATION 75 PROTEIN 77 CARBOHYDRATES 81 INTELLIGENCE 81 SOCIAL DYNAMICS 83 CULTURE 86 MATING & CHILD REARING 87 LIFE HISTORY 91 GROUP SIZE 93 SEXUAL DIMORPHISM 93 DIVISION OF LABOR 95 FOOD SHARING 98 CHIMPS 98 CULTURE 101 CARE FOR OTHERS 102 References 103 HOMO ERECTUS Extinction of Early Homo, Homo Rudolfensis & Habilis, and the Emergence of Erectus Around two million years ago, another hominid emerged in Africa called Homo Erectus that survived for over one million years, becoming extinct only about one hundred and fifty thousand years ago. At the beginning of its existence, it evidently co-existed with both Homo Hablis and Rudolfensis, as well as Australopithecus Boisei and at the end of its time, it overlapped with itself, Homo Sapien. In any case, soon after its emergence, Homo Habilis and Rudolfensis went extinct; at least that is what we have concluded based on our limited number of fossils. -

Relevance of Aquatic Environments for Hominins: a Case Study from Trinil (Java, Indonesia)

Journal of Human Evolution 57 (2009) 656–671 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Human Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jhevol Relevance of aquatic environments for hominins: a case study from Trinil (Java, Indonesia) J.C.A. Joordens a,*, F.P. Wesselingh b, J. de Vos b, H.B. Vonhof a, D. Kroon c a Institute of Earth Sciences, VU University Amsterdam, De Boelelaan 1056, 1051 HV Amsterdam, The Netherlands b Naturalis National Museum of Natural History , P.O. Box 9517, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands c School of Geosciences, The University of Edinburgh, West Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3JW, UK article info abstract Article history: Knowledge about dietary niche is key to understanding hominin evolution, since diet influences body Received 31 December 2008 proportions, brain size, cognition, and habitat preference. In this study we provide ecological context for Accepted 9 April 2009 the current debate on modernity (or not) of aquatic resource exploitation by hominins. We use the Homo erectus site of Trinil as a case study to investigate how research questions on possible dietary relevance of Keywords: aquatic environments can be addressed. Faunal and geochemical analysis of aquatic fossils from Trinil Hominin evolution Hauptknochenschicht (HK) fauna demonstrate that Trinil at w1.5 Ma contained near-coastal rivers, lakes, Strontium isotopes swamp forests, lagoons, and marshes with minor marine influence, laterally grading into grasslands. Freshwater wetland Marine influence Trinil HK environments yielded at least eleven edible mollusc species and four edible fish species that Stingray could be procured with no or minimal technology. We demonstrate that, from an ecological point of Fish view, the default assumption should be that omnivorous hominins in coastal habitats with catchable Molluscs aquatic fauna could have consumed aquatic resources. -

Another Look at the Jakarta Charter Controversy of 1945

Another Look at the Jakarta Charter Controversy of 1945 R. E. Elson* On the morning of August 18, 1945, three days after the Japanese surrender and just a day after Indonesia's proclamation of independence, Mohammad Hatta, soon to be elected as vice-president of the infant republic, prevailed upon delegates at the first meeting of the Panitia Persiapan Kemerdekaan Indonesia (PPKI, Committee for the Preparation of Indonesian Independence) to adjust key aspects of the republic's draft constitution, notably its preamble. The changes enjoined by Hatta on members of the Preparation Committee, charged with finalizing and promulgating the constitution, were made quickly and with little dispute. Their effect, however, particularly the removal of seven words stipulating that all Muslims should observe Islamic law, was significantly to reduce the proposed formal role of Islam in Indonesian political and social life. Episodically thereafter, the actions of the PPKI that day came to be castigated by some Muslims as catastrophic for Islam in Indonesia—indeed, as an act of treason* 1—and efforts were put in train to restore the seven words to the constitution.2 In retracing the history of the drafting of the Jakarta Charter in June 1945, * This research was supported under the Australian Research Council's Discovery Projects funding scheme. I am grateful for the helpful comments on and assistance with an earlier draft of this article that I received from John Butcher, Ananda B. Kusuma, Gerry van Klinken, Tomoko Aoyama, Akh Muzakki, and especially an anonymous reviewer. 1 Anonymous, "Naskah Proklamasi 17 Agustus 1945: Pengkhianatan Pertama terhadap Piagam Jakarta?," Suara Hidayatullah 13,5 (2000): 13-14. -

The Pesantren in Banten: Local Wisdom and Challenges of Modernity

The Pesantren in Banten: Local Wisdom and Challenges of Modernity Mohamad Hudaeri1, Atu Karomah2, and Sholahuddin Al Ayubi3 {[email protected], [email protected], [email protected]} Faculty of Ushuluddin and Adab, State Islamic University SMH Banten, Jl. Jend. Sudirman No. 30, Serang, Indonesia1 Faculty of Syariah, State Islamic University SMH Banten, Jl. Jend. Sudirman No. 30, Serang, Indonesia2 Faculty of Ushuluddin and Adab, State Islamic University SMH Banten, Jl. Jend. Sudirman No. 30, Serang, Indonesia3 Abstract. Pesantrens (Islamic Boarding School) are Islamic educational institutions in Indonesia that are timeless, because of their adaptability to the development of society. These educational institutions develop because they have the wisdom to face changes and the ability to adapt to the challenges of modernity. During the colonial period, pesantren adapted to local culture so that Islam could be accepted by the Banten people, as well as a center of resistance to colonialism. Whereas in contemporary times, pesantren adapted to the demands of modern life. Although due to the challenges of modernity there are various variants of the pesantren model, it is related to the emergence of religious ideology in responding to modernity. The ability of pesantren in adapting to facing challenges can‘t be separated from the discursive tradition in Islam so that the scholars can negotiate between past practices as a reference with the demands of the age faced and their future. Keywords: pesantren, madrasa, Banten, a discursive tradition. 1. Introduction Although Islamic educational institutions (madrasa and pesantren) have an important role in the Muslim community in Indonesia and in other Muslim countries, academic studies that discuss them are still relatively few. -

The History of Prehistoric Research in Indonesia to 1950

The History of Prehistoric Research in Indonesia to 1950 Received 16 January 1968 R. P. SOE]ONO INTRODUCTION HE oldest description of material valuable for prehistoric recording in future times was given by G. E. Rumphius at the beginning of the eighteenth century. Rum T phius mentioned the veneration of historical objects by local peoples, and even now survivals of the very remote past retain their respect. On several islands we also notice a continuation of prehistoric traditions and art. Specific prehistoric relics, like many other archaeological remains, are holy to most of the inhabitants because of their quaint, uncommon shapes. As a result, myths are frequently created around these objects. An investigator is not permitted to inspect the bronze kettle drum kept in a temple at Pedjeng (Bali) and he must respect the people's devout feelings when he attempts to observe megalithic relics in the Pasemah Plateau (South Sumatra); these facts accentuate the persistence oflocal veneration even today. In spite of the veneration of particular objects, which in turn favors their preservation, many other relics have been lost or destroyed through digging or looting by treasure hunters or other exploiters seeking economic gain. Moreover, unqualified excavators have com pounded the problem. P. V. van Stein Callenfels, originally a specialist in Hindu-Indonesian archaeology, be came strongly aware of neglect in the field of prehistoric archaeology, and he took steps to begin systematic research. During his visit to kitchen middens in East Sumatra during a tour of inspection in 1920 for the Archaeological Service, he met with the digging of shell heaps for shell for limekilns. -

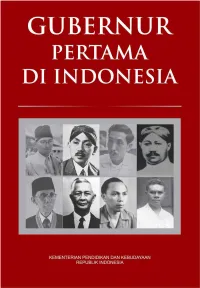

Teuku Mohammad Hasan (Sumatra), Soetardjo Kartohadikoesoemo (Jawa Barat), R

GUBERNUR PERTAMA DI INDONESIA GUBERNUR PERTAMA DI INDONESIA KEMENTERIAN PENDIDIKAN DAN KEBUDAYAAN REPUBLIK INDONESIA GUBERNUR PERTAMA DI INDONESIA PENGARAH Hilmar Farid (Direktur Jenderal Kebudayaan) Triana Wulandari (Direktur Sejarah) NARASUMBER Suharja, Mohammad Iskandar, Mirwan Andan EDITOR Mukhlis PaEni, Kasijanto Sastrodinomo PEMBACA UTAMA Anhar Gonggong, Susanto Zuhdi, Triana Wulandari PENULIS Andi Lili Evita, Helen, Hendi Johari, I Gusti Agung Ayu Ratih Linda Sunarti, Martin Sitompul, Raisa Kamila, Taufik Ahmad SEKRETARIAT DAN PRODUKSI Tirmizi, Isak Purba, Bariyo, Haryanto Maemunah, Dwi Artiningsih Budi Harjo Sayoga, Esti Warastika, Martina Safitry, Dirga Fawakih TATA LETAK DAN GRAFIS Rawan Kurniawan, M Abduh Husain PENERBIT: Direktorat Sejarah Direktorat Jenderal Kebudayaan Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan Jalan Jenderal Sudirman, Senayan Jakarta 10270 Tlp/Fax: 021-572504 2017 ISBN: 978-602-1289-72-3 SAMBUTAN Direktur Sejarah Dalam sejarah perjalanan bangsa, Indonesia telah melahirkan banyak tokoh yang kiprah dan pemikirannya tetap hidup, menginspirasi dan relevan hingga kini. Mereka adalah para tokoh yang dengan gigih berjuang menegakkan kedaulatan bangsa. Kisah perjuangan mereka penting untuk dicatat dan diabadikan sebagai bahan inspirasi generasi bangsa kini, dan akan datang, agar generasi bangsa yang tumbuh kelak tidak hanya cerdas, tetapi juga berkarakter. Oleh karena itu, dalam upaya mengabadikan nilai-nilai inspiratif para tokoh pahlawan tersebut Direktorat Sejarah, Direktorat Jenderal Kebudayaan, Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan menyelenggarakan kegiatan penulisan sejarah pahlawan nasional. Kisah pahlawan nasional secara umum telah banyak ditulis. Namun penulisan kisah pahlawan nasional kali ini akan menekankan peranan tokoh gubernur pertama Republik Indonesia yang menjabat pasca proklamasi kemerdekaan Indonesia. Para tokoh tersebut adalah Teuku Mohammad Hasan (Sumatra), Soetardjo Kartohadikoesoemo (Jawa Barat), R. Pandji Soeroso (Jawa Tengah), R. -

The Dubois Collection: a New Look at an Old Collection

The Dubois collection: a new look at an old collection John de Vos Vos, }. de. The Dubois collection: a new look at an old collection. In: Winkler Prins, CF. & Donovan, S.K. (eds.), VII International Symposium 'Cultural Heritage in Geosciences, Mining and Metallurgy: Libraries - Archives - Museums': "Museums and their collections", Leiden (The Netherlands), 19-23 May 2003. Scripta Geologic, Special Issue, 4: 267-285, 9 figs.; Leiden, August 2004. J. de Vos, Department of Palaeontology, Nationaal Natuurhistorisch Museum Naturalis, P.O. Box 9517, NL-2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands ([email protected]). Key words - Dubois, Pithecanthropus erectus, Homo erectus, Homo sapiens, Java. One of the most exciting episodes of paleoanthropology was the find of the first transitional form, the Pithecanthropus erectus, by the Dutchman Eugène Dubois in Java during 1891-1892. The history of Dubois and his finds of the molar, skullcap and femur, forming his transitional form, are described. Besides the human remains, Dubois made a large collection of vertebrate fossils, mostly of mammals, now united in the so-called Dubois Collection. This collection played an important role in unravelling the biostratigraphy and chronostratigraphy of Java. Questions, such as from where were those mam• mals coming, when did Homo erectus arrive in Java, and when did it become extinct, and when did Homo sapiens reach Java, are discussed. Contents Introduction 267 Early theories about the evolution of Man 268 The role of Dubois (1858-1940) in paleoanthropology ... 269 Important hominid sites of Java 273 The role of the Dubois Collection in biostratigraphy 274 Dispersal of faunas in southeast Asia 276 The chronostratigraphy of Java 279 Time of arrival of Homo erectus and Homo sapiens in Java 280 Conclusions 281 References 282 Introduction The Dubois Collection of vertebrate fossils was made by Eugène Dubois in the former Netherlands East Indies, nowadays Indonesia, at the end of the 19th century. -

Exploring the History of Indonesian Nationalism

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM Graduate College Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 2021 Developing Identity: Exploring The History Of Indonesian Nationalism Thomas Joseph Butcher University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis Part of the Asian History Commons, and the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Butcher, Thomas Joseph, "Developing Identity: Exploring The History Of Indonesian Nationalism" (2021). Graduate College Dissertations and Theses. 1393. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis/1393 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate College Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEVELOPING IDENTITY: EXPLORING THE HISTORY OF INDONESIAN NATIONALISM A Thesis Presented by Thomas Joseph Butcher to The Faculty of the Graduate College of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Specializing in History May, 2021 Defense Date: March 26, 2021 Thesis Examination Committee: Erik Esselstrom, Ph.D., Advisor Thomas Borchert, Ph.D., Chairperson Dona Brown, Ph.D. Cynthia J. Forehand, Ph.D., Dean of the Graduate College Abstract This thesis examines the history of Indonesian nationalism over the course of the twentieth century. In this thesis, I argue that the country’s two main political leaders of the twentieth century, Presidents Sukarno (1945-1967) and Suharto (1967-1998) manipulated nationalist ideology to enhance and extend their executive powers. The thesis begins by looking at the ways that the nationalist movement originated during the final years of the Dutch East Indies colonial period. -

Cover + Tulisan Prof Dudung, Religious

Adab-International Conference on Information and Cultural Sciences 2020 Yogyakarta, October 19th-22nd, 2020 ISSN: 2715-0550 RELIGIOUS MODERATION IN THE TRADITION OF CONTEMPORARY SUFISM IN INDONESIA Dudung Abdurahman A. Preface Islamic religious life in Indonesia has recently grown in diversity and massive differences. Therefore, efforts to seek religious moderation are carried out by various parties in order to find alternative methods, models or solutions for overcoming various symptoms of conflict, and finding a harmony atmosphere of the people in this country. The search for a model of religious moderation can actually be carried out on its potential in the realm of Islam itself. As is well known, the Islamic teaching system is based on the Quran and Hadith, then it becomes the Islamic trilogy: Aqidah (belief), Syari'ah (worship and muamalah), and Akhlak (tasawwuf). Each of these aspects developed in the thought of the scholars who gave birth to various ideologies and genres according to the historical and socio- cultural context of the Muslim community. Meanwhile, tasawuf or sufism is assumed to have more unique and significant potential for religious moderation, because Sufism which is oriented towards the formation of Islam is moderate, both in thought, movement and religious behavior in Muslim societies. The general significance of Sufism can be seen in its history in the spread of Islam to various parts of the world. John Renard, for example, mentions that Sufism plays a conducive role for the spread of Islam, because Sufism acts as a "mystical expression of the Islamic faith" (Renard, 1996: 307). Similarly, Marshall G.S. -

Early Hominidshominids

EarlyEarly HominidsHominids TheThe FossilFossil RecordRecord TwoTwo StoriesStories toto Tell:Tell: 1.1. HowHow hominidshominids evolvedevolved 2.2. HowHow interpretationsinterpretations changechange InsightInsight intointo processprocess PastPast && futurefuture changeschanges InteractingInteracting elements...elements... InterplayInterplay ofof ThreeThree ElementsElements “Hard” evidence Fossils Archeological associations Explanation Dates Reconstructions Anatomy Behavior Phylogeny Reconstruction Evidence Explanatory Frames Why did it happen? What does it mean? MutualMutual InfluenceInfluence WhereWhere toto start?start? SouthSouth Africa,Africa, 19241924 TaungTaung ChildChild Raymond Dart, 1924 Taung, South Africa Why did Dart call it a Hominid? TaungTaung ChildChild Raymond Dart, 1924 Taung, South Africa Australopithecus africanus 2.5 mya Four-year old with an ape-sized brain, humanlike small canines, and foramen magnum shifted forward NeanderthalNeanderthal HomoHomo sapienssapiens neanderthalensis neanderthalensis NeanderNeander Valley,Valley, Germany, Germany, 18561856 Age: 40-50,000 Significance: First human fossil acknowledged as such, and first specimen of Neanderthal. First dismissed as a freak, but Doctor J. C. Fuhlrott speculated that it was an ancient human. TrinilTrinil 1:1: “Java“Java Man”Man” HomoHomo erectuserectus Eugene Dubois, 1891 Trinil, Java, Indonesia Age: 500,000 yrs Significance: The Java hominid, originally classified as Pithecanthropus erectus, was the controversial “missing link” of its day. -

Global and Local Perspectives on Cranial Shape Variation in Indonesian Homo Erectus

ANTHROPOLOGICAL SCIENCE Vol. 125(2), 67–83, 2017 Global and local perspectives on cranial shape variation in Indonesian Homo erectus Karen L. BAAB1*, Yahdi ZAIM2 1Department of Anatomy, Midwestern University, Arizona College of Osteopathic Medicine, 19555 N. 59th Avenue, Glendale, AZ 85012, USA 2Department of Geology, Institut Technologi Bandung (ITB), Jl. Ganesa No. 10, Bandung–40132, Indonesia Received 5 December 2016; accepted 13 April 2017 Abstract Homo erectus is among the best-represented fossil hominin species, with a particularly rich record in Indonesia. Understanding variation within this sample and relative to other groups of H. erectus in China, Georgia, and Africa is crucial for answering questions about H. erectus migration, local adap- tation, and evolutionary history. Neurocranial shape is analyzed within the Indonesian sample, including representatives from Sangiran, Ngandong, Sambungmacan, and Ngawi, as well as a comparative sample of H. erectus from outside of Java, using three-dimensional geometric morphometric techniques. This study includes several more recently described Indonesian fossils, including Sambungmacan 4 and Skull IX, producing a more complete view of Indonesian variation than seen in previous shape analyses. While Asian fossils can be distinguished from the African/Georgian ones, there is not a single cranial Bauplan that distinguishes all Indonesian fossils from those in other geographic areas. Nevertheless, late Indone- sian H. erectus, from sites such as Ngandong, are quite distinct relative to all other H. erectus groups, including earlier fossils from the same region. It is possible that this pattern represents a loss of genetic diversity through time on the island of Java, coupled with genetic drift, although other interpretations are plausible.