To What Extent Was Catholicism in Wales Still

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thames Valley Papists from Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829

Thames Valley Papists From Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829 Tony Hadland Copyright © 1992 & 2004 by Tony Hadland All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without prior permission in writing from the publisher and author. The moral right of Tony Hadland to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 0 9547547 0 0 First edition published as a hardback by Tony Hadland in 1992. This new edition published in soft cover in April 2004 by The Mapledurham 1997 Trust, Mapledurham HOUSE, Reading, RG4 7TR. Pre-press and design by Tony Hadland E-mail: [email protected] Printed by Antony Rowe Limited, 2 Whittle Drive, Highfield Industrial Estate, Eastbourne, East Sussex, BN23 6QT. E-mail: [email protected] While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, neither the author nor the publisher can be held responsible for any loss or inconvenience arising from errors contained in this work. Feedback from readers on points of accuracy will be welcomed and should be e-mailed to [email protected] or mailed to the author via the publisher. Front cover: Mapledurham House, front elevation. Back cover: Mapledurham House, as seen from the Thames. A high gable end, clad in reflective oyster shells, indicated a safe house for Catholics. -

The Gunpowder Plot: Terror and Faith in 1605 PDF Book

THE GUNPOWDER PLOT: TERROR AND FAITH IN 1605 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Antonia Fraser | 448 pages | 01 Feb 2003 | Orion Publishing Co | 9780753814017 | English | London, United Kingdom The Gunpowder Plot: Terror and Faith in 1605 PDF Book Before he died Tresham had also told of Garnet's involvement with the mission to Spain, but in his last hours he retracted some of these statements. The King insisted that a more thorough search be undertaken. Thomas Wintour begged to be hanged for himself and his brother, so that his brother might be spared. Thomas Wintour and Littleton, on their way from Huddington to Holbeche House, were told by a messenger that Catesby had died. Details of the assassination attempt were allegedly known by the principal Jesuit of England, Father Henry Garnet. Synopsis About this title With a narrative that grips the reader like a detective story, Antonia Fraser brings the characters and events of the Gunpowder Plot to life. Seven of the prisoners were taken from the Tower to the Star Chamber by barge. As news of "John Johnson's" arrest spread among the plotters still in London, most fled northwest, along Watling Street. Seller Inventory aa2a43fc1e57f0bdf. At first glance, it might seem a little odd that I am reading a book so closely connected with November and Bonfire Night at the beginning of August. He also spoke of a Christian union and reiterated his desire to avoid religious persecution. Macbeth , Act 2 Scene 3. This is a complex story, with many players, both high and low, but Fraser lays it out clearly and concisely. -

Catholic Church 8500 N

SAINT HENRY CATHOLIC CHURCH 8500 N. Owasso Expressway Owasso, OK 74055 | (918) 272-3710 | sthenryowasso.org | August 30, 2020 Twenty-second Sunday in Ordinary Time 30 de Agosto, 2020 Vigésino-segundo domingo en Tiempo Ordinario Parish Information Información Parroquial Rev. Matt La Chance, Pastor [email protected] Rev. Bala Yaddanapalli, Associate Pastor ext.110 [email protected] Deacon Edmundo Martinez Deacon Larry Schneider Deacon Emeritus Vernon Foltz Deacon Emeritus Don LeMieux In the event of sacramental emergencies, call 918.609.6542. En caso de emergencias sacramentales, llame al 918.609.6542. Business Manager Denise Haffner [email protected] ext.100 Coordinator of Faith Formation Laura Valdez [email protected] ext. 105 Coordinator of Youth Ministry Katie Salamon [email protected] ext. 102 Faith Formation Secretary Kathy Hendricks [email protected] ext. 104 Coordinator of Ministries Sahira Bravo [email protected] ext. 107 FebruaryJulyAugustSeptember 29, 5,30, 2018 4, 2018 2020 24, 2018 2017 Seventeenth Eighteenth Fifth Twenty-fifth SundaySunday Sunday in in Sunday in Ordinary Ordinary Ordinary Twenty-second in Ordinary TimeTime Time Time Sunday in Ordinary Time Weekly Calendar Calendario Semanal Sun., Aug. 30 Mass Dom. 30, Ago. Misa Mon., Aug. 31 Daily Mass Lun. 31, Ago. Misa Diaria Tue., Sept. 1 Daily Mass Mar. 1°, Set. Misa Diaria Wed., Sept. 2 Daily Mass Mié. 2, Set. Misa Diaria Thu., Sept. 3 Daily Mass Jue. 3, Set. Misa Diaria Fri., Sept. 4 Daily Mass Vie. 4, Set. Misa Diaria Mass Misa Sat., Sept. 5 Sáb. 5, Set. Confession Confesiones Mass Intentions/Intenciones: Aug. 29—Sept. 4 / Del 29 de Ago. -

The Reformation

The Reformation Characters of the Reformation Hilaire Belloc In bold living colours Belloc sketches 23 famous men and women of the Reformation period, analysing their strengths, weaknesses, mistakes and motives and pinpointing deeds that changed the course of history. There are more than a few surprises here, as Belloc often puts the real responsibility for the Reformation on persons not usually appreciated by history. He describes the characters and deeds of real people, tracing the results of their greed, lust, tenacity, blindness, fear and - in the case of St Thomas More - heroic Catholic constancy. TAN 978 089555466 6 210 pages £7.99 How the Reformation Happened Hilaire Belloc Belloc provides a largely untold story that answers a critical historical question about Western civilization: How did Christendom come to suffer shipwreck in the Protestant Reformation? He admits that corruption among churchmen and clerical abuses in the use of church revenues prepared the way for the flood of revolt. But he uncovers other, more decisive, factors involved in the movement. He demonstrates that it was not doctrine, but rather avarice and rebellion against the clergy, that originally fuelled the Reformation. TAN 978 089555465 9 224 pages £7.99 Luther and His Progeny Edited by John C Rao 500 Years of Protestantism & Its Consequences for Church, State and Society A brilliant collection of essays examining Martin Luther's role in the dissolution of medieval Christendom and his influence on subsequent developments. Anyone who wants to understand the long decline from the Catholic Middle Ages to the secular present will find a wealth of insight in this book. -

Gunpowder, Treason and York

Gunpowder, treason and York Marianka Swain explores the birthplace of Guy Fawkes, and separates fact from enduring myth MAP ILLUSTRATION: REBECCA LEA WILLIAMS LEA REBECCA ILLUSTRATION: MAP discoverbritainmag.com 37 York Clockwise, from left: The Shambles hide a violent past; All Saints Pavement; the street’s overhanging design protected the meat traded there; the Guy Fawkes Inn; St Michael le Belfry; the plot is discovered Previous page: A 19th-century wood engraving of Guy Fawkes and his fellow conspirators ALAMY/PORTRAIT ESSENTIALS/CW IMAGES/CLEARVIEW/MSP TRAVEL IMAGES/TOMMY (LOUTH)/ HERITAGE IMAGE PARTNERSHIP LTD/VISITBRITAIN/ANDREW PICKETT LTD/VISITBRITAIN/ANDREW PARTNERSHIP IMAGE HERITAGE (LOUTH)/ IMAGES/TOMMY TRAVEL ALAMY/PORTRAIT IMAGES/CLEARVIEW/MSP ESSENTIALS/CW emember, remember, the fifth immediate family were Protestants: he and Pulleyn and Percy families in Scotton. From sympathies: his home city was teeming with “Contrary to of November” rings out across his sisters were baptised in the 16th-century 1582, he attended St Peter’s School in York gruesome tales. York’s All Saints Pavement Britain, as notorious plotter Guy St Michael le Belfrey Church, which today with brothers John and Christopher “Kit” church houses the replicas of the helmet, popular opinion, Fawkes is burned in effigy on features a facsimile of his baptismal entry. Wright, who later joined the Gunpowder sword and gauntlets of Thomas Percy, the conspiracy was RBonfire Night. His part in the failed 1605 His father was a proctor and advocate at Plot, and future priests Oswald Tesimond, 7th Earl of Northumberland, who led the Gunpowder Plot still echoes through history, the Archbishop’s consistory court, and died Edward Oldcorne and Robert Middleton. -

Recusant Literature Benjamin Charles Watson University of San Francisco, [email protected]

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Gleeson Library Librarians Research Gleeson Library | Geschke Center 2003 Recusant Literature Benjamin Charles Watson University of San Francisco, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.usfca.edu/librarian Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, History Commons, Library and Information Science Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Watson, Benjamin Charles, "Recusant Literature" (2003). Gleeson Library Librarians Research. Paper 2. http://repository.usfca.edu/librarian/2 This Bibliography is brought to you for free and open access by the Gleeson Library | Geschke Center at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Gleeson Library Librarians Research by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RECUSANT LITERATURE Description of USF collections by and about Catholics in England during the period of the Penal Laws, beginning with the the accession of Elizabeth I in 1558 and continuing until the Catholic Relief Act of 1791, with special emphasis on the Jesuit presence throughout these two centuries of religious and political conflict. Introduction The unpopular English Catholic Queen, Mary Tudor died in 1558 after a brief reign during which she earned the epithet ‘Bloody Mary’ for her persecution of Protestants. Mary’s Protestant younger sister succeeded her as Queen Elizabeth I. In 1559, during the first year of Elizabeth’s reign, Parliament passed the Act of Uniformity, declaring the state-run Church of England as the only legitimate religious authority, and compulsory for all citizens. -

St. Nicholas Owen (Ca

St. Nicholas Owen (ca. 1561–1606) Lawrence M. Ober, SJ ST. NICHOLAS Owen was a Jesuit lay brother famed for creating and building “priest holes” in England for priests who were secretly ministering to Catholics at end of the sixteenth and the beginning of the seventeenth century. 1 Background Legend and reconstructed history suggest that he was born into a recusant family in Oxford about 1561. Recusants were Catholics who refused to conform to the Anglican Church— which had become more Protestant during the reigns of King Edward VI (1547–1553) and his half-sister, Queen Elizabeth (1558–1603), with a short period between 1553 and 1558 during which yet another half-sister, Queen Mary, attempted to restore Catholicism in the kingdom. Nicholas’s father is thought to have been a carpenter, and among Nicholas’s siblings very likely were brothers John and Walter, who became secret Catholic priests, and another brother, Henry who clandestinely printed and distributed Catholic literature. As was common with most Jesuits in England and America, Nicholas often operated under an assumed name. We have no knowledge of his physical features; but, since his alias was “Little John,” people surmise that he was very short—or perhaps very tall, since the name might have been a joke. He also was known as “little Michael,” and as “Andrews” or “Draper.” It is known that he suffered from a hernia and also bad legs—a life-long legacy after falling from a horse. At some point, Nicholas was secretly admitted to the Society of Jesus (Jesuits), although there is no record of his formally making novitiate or taking vows. -

Why Are Nuns Funny?

Why Are Nuns Funny? Frances E. Dolan ! !" #"$%&"' & $#"#(&)!*" *( )+* a;er the Reformation, the nun was a stock <gure in a surprisingly wide range of representations. She appears in mis - chievous ballads; in comedies (where, from the poisoned nuns in !e Jew of Malta to the wise abbess in !e Comedy of Errors, the nun is either silly or benign rather than a female version of the misguided friars and villainous cardinals of tragedy); in earnest exposés of Catholic corruption; in erotic elaborations of what might happen inside the cloister and inside the confessional; in the occasional biography of a nun by her con - fessor or abbess; in theological treatises and guides addressed to her; and in the letters and other writings nuns themselves composed. Except for texts produced by and for Catholics, most of these texts provoke laughter at the nun’s failed attempts at chastity, her misguided obedience, her superstition, and her presumption to authority.= Since nuns were as various as anyone else, and representations of them spanned centuries, appearing in a range of genres and addressed to a great variety of readers, the polemi- cal project of ridiculing the nun needs to be scrutinized rather than taken as given. >e laughable nun is exposed to hostile view from the outside. Her exposure is designed in part to secure the alienated position from which one observes and ridicules her. From this viewpoint, she <gures that part of Catholicism that is to be d ismissed rather than feared: the absurdity of female authority and separatism; the inevitable eruption of repression into license; the mindless submission to corrupt leaders. -

Constituencies (Shorter Version)

Constituencies (Shorter Version) (Terms in bold italics are explained further in the Glossary, terms underlined have their own articles) Introduction Today, Members of Parliament are elected by voters divided into 650 constituencies. Each constituency is made up of roughly the same number of voters. In Tudor times each county elected two members (except for Wales, whose counties only elected one) and some boroughs (often towns) also elected MPs. MPs were not elected in secret as they are today, and you could not vote unless you owned property. Many owed their seats to powerful landowners or patrons who wanted MPs to represent their own interests in Parliament. Engraved title-page to William Camden's 'Britannia' (1607) Some towns, such as Newcastle, were able to pay their MPs salaries, which © The Trustees of the meant these MPs were more independent and elected by the leading men in the British Museum town. It was a very different system than it is now! Below are descriptions of different constituencies across England and Wales. They show how differently the Reformation happened across the country. For example, Protestantism gained more followers in the South, East, and in the towns. Many areas in the North and West had large numbers of Catholics well into Elizabeth’s reign. We have tried to show the effect the Reformation had on ordinary people, although this is not always easy as the evidence is limited. In some areas the Reformation brought about major changes to local politics. There were rebellions: some pro-Catholic (such as the Pilgrimage of Grace in Lincolnshire and Knaresborough, Yorkshire), some more Protestant (such as Wyatt’s rebellion in Kent). -

Quick Definitions

Learning Resources for Schools Quick Definitions A member of the Roman Catholic Church, which has the Catholic Pope as its head A place of worship, like the one hidden here in the Bar Chapel Convent A group of people who gather together for religious Congregation worship The religious congregation to which the Bar Convent sisters Congregation of Jesus belong, established by Mary Ward Convent A place where nuns live together A way of religious life where people devote themselves Contemplative completely to prayer and silence, without active work in the world The ordinary life for nuns in Mary Ward’s time – behind a Enclosed convent wall, with little contact with the outside world The period of religious upheaval started by Henry VIII’s split English Reformation from the Catholic church. This led to the creation of the Church of England. A member of the Society of Jesus, founded by Ignatius of Loyola in 1540 to do missionary work. Jesuit priests came Jesuit to England after the Reformation to support Catholics in their faith, and make new converts. Martyr Someone who dies for their faith Missionary A religious person who goes out across the world to spread 1 God’s message Mother Superior The sister who is in charge of a convent A woman who takes religious vows to live her life in Nun devotion to God An attack on people because of their religious or political Persecution beliefs Pope Head of the Catholic Church, who lives in Rome A hiding place in a house during the recusant period where Priest Hole priests had to hide if the authorities came searching A member of one of the churches set up after the Protestant Reformation Someone who, during the time of people like Margaret Recusant Clitherow, did not attend their Anglican parish church when they were supposed to by law. -

Clwyd Historian Index to Articles Issue 1 1977

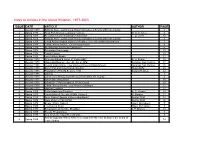

Index to Articles in the Clwyd Historian, 1977-2005 ISSUE DATE ARTICLE AUTHOR PAGE 1 Autumn 1977 Editorial Note - List of Local History Societies & Events within the County 1 2 Spring 1978 Rhyn Park Roman Legionary Fortress G. D. B Jones 5 2 Spring 1978 All Saints Church at Llangar in Edeirnion T. O. Jones 10 2 Spring 1978 Editorial Note - List of Local History Societies & Events within the County 1 2 Spring 1978 Clwyd Archaeological Volunteer Register - Greenfield Mills Excavations 7 2 Spring 1978 Clwyd Library Service - Oral History Project 8 2 Spring 1978 An Historical Society for Edeyrnion? 9 2 Spring 1978 Recording Graveyards 10 2 Spring 1978 Family History 10 2 Spring 1978 Local History Books 11 3 Autumn 1978 Who was Edward Jones of Wepre Hall? D. G. Evans 15 3 Autumn 1978 Notes and Queries - Aer, Air, Ayr or Offa? Goronwy Alun Hughes 17 3 Autumn 1978 Recent Publications - Lles Cymru articles of Clwyd Interest Goronwy Alun Hughes 26 3 Autumn 1978 Bryn Y Pys and Gwernhaled, Overton Helen Duffy 28 3 Autumn 1978 Population of Flint M.B. since 1891 Zuzana Hughes 22 3 Autumn 1978 Editorial 1 3 Autumn 1978 List of Local History Societies & Events within the County 2 3 Autumn 1978 Information Requested 19 3 Autumn 1978 Exhibition of Photographs at Theatr Clwyd 20 3 Autumn 1978 Clwyd Library Service Local History Catalogue 21 3 Autumn 1978 Harvest Customs 21 4 Spring 1979 Puffin Island and Flintshire A. G. Veysey 19 4 Spring 1979 Excavations at Greenfield Mills, Holywell D. Morgan 11 4 Spring 1979 Does Rossett Appear in Domesday Book? Derrick Pratt 13 4 Spring 1979 Point of Ayr or Point Offa? Derrick Pratt 16 4 Spring 1979 Beware Place Names! Hywel Wyn Owen 8 4 Spring 1979 The Roman Road Hywel Wyn Owen 9 4 Spring 1979 Excavations at Hendre, Rhuddlan J. -

Boscobel House and the Royal Oak Teachers'

KS1-2KS1–2 KS3 TEACHERS’ KIT KS4 Boscobel House and the Royal Oak SEND This kit helps teachers plan a visit to Boscobel House and the Royal Oak. Boscobel played a brief but important role in the English Civil War when it sheltered and hid the future King Charles II. Use these resources before, during and after your visit to help students get the most out of their learning. GET IN TOUCH WITH OUR EDUCATION BOOKINGS TEAM: 0370 333 0606 [email protected] bookings.english-heritage.org.uk/education Share your visit with us on Twitter @EHEducation The English Heritage Trust is a charity, no. 1140351, and a company, no. 07447221, registered in England. All images are copyright of English Heritage or Historic England unless otherwise stated. Published March 2021 WELCOME This Teachers’ Kit for Boscobel House and the Royal Oak has been designed for teachers and group leaders to support a free self-led visit to the site. It includes a variety of materials suited to teaching a wide range of subjects and key stages, with practical information, activities for use on site and ideas to support follow-up learning. We know that each class and study group is different, so we have collated our resources into one kit allowing you to decide which materials are best suited to your needs. Please use the contents page, which has been colour- coded to help you easily locate what you need and view individual sections. All of our activities have clear guidance on the intended use for study so you can adapt them for your desired learning outcomes.