Solitary Sparrows: Widowhood and the Catholic Community In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Books List October-December 2011

New Books List October-December 2011 This catalogue of the Shakespeare First Folio (1623) is the result of two decades of research during which 232 surviving copies of this immeasurably important book were located – a remarkable 72 more than were recorded in the previous census over a century ago – and examined in situ, creating an essential reference work. ෮ Internationally renowned authors Eric Rasmussen, co-editor of the RSC Shakespeare series and Professor of English at the University of Nevada, Reno, USA; Anthony James West, Shakespeare scholar, focused on the history of the First Folio since it left the press. ෮ Full bibliographic descriptions of each extant copy, including detailed accounts of press variants, watermarks, damage or repair and provenance ෮ Fascinating stories about previous owners and incidents ෮ Striking Illustrations in a colour plate section ෮ User’s Guide and Indices for easy cross referencing ෮ Hugely significant resource for researchers into the history of the book, as well as auction houses, book collectors, curators and specialist book dealers November 2011 | Hardback | 978-0-230-51765-3 | £225.00 For more information, please visit: www.palgrave.com/reference Order securely online at www.palgrave.com or telephone +44 (0)1256 302866 fax + 44(0)1256 330688 email [email protected] Jellybeans © Andrew Johnson/istock.com New Books List October-December 2011 KEY TO SYMBOLS Title is, or New Title available Web resource as an ebook Textbook comes with, a available CD-ROM/DVD Contents Language and Linguistics 68 Anthropology -

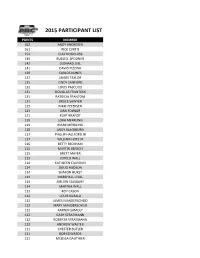

2015 Abcs Membersht.Csv

2015 PARTICIPANT LIST POINTS MEMBER 162 ANDY ANDRESEN 161 RICK CURTIS 152 CLAY DOUGLASS 145 RUSSELL SPOONER 142 LEONARD DILL 141 DAVID PIZZINO 139 CARLOS NUNES 137 JAMESTAYLOR 135 CINDY SANFORD 132 LOUIS PASCUCCI 131 DOUGLAS FRANTOM 131 PATRICIA FRANTOM 131 BRUCE SAWYER 125 NIKKI PETERSEN 123 DANFOWLER 121 KURT BRANDT 119 LORA MERKLING 119 MARK MERKLING 118 ANDY BLACKBURN 117 PHILLIP HALLFORD JR 117 WILLIAM HOTZ JR 116 BETTY BECKHAM 115 MARTIN BENSCH 115 BRETT MAYER 115 JEROLD WALL 114 KATHLEEN CALHOUN 114 DOUG HUDSON 114 SHARON HURST 114 MARSHALL LYALL 114 MELVIN SALSBURY 114 MARTHA WALL 113 ROY CASON 112 LOUIS KUBALA 112 JAMES MANDERSCHEID 112 MARY MANDERSCHEID 112 KAYREN SAMOLY 112 GARY STRATMANN 112 ROBERTA STRATMANN 112 ANDREW WALTER 111 CHESTER BUTLER 111 BOB EDWARDS 111 MELISSA GAUTHIER 111 LARRY LANGLINAIS 111 FREDERICK MCKAY 111 JAMES PIRTLE 111 THELMA PIRTLE 110 JOHN BRATSCHUN 110 NORMA EDWARDS 110 JEFF MCCLAIN 110 SANDRA MCCLAIN 110 MICHAEL PRITCHETT 110 CAROL TIMMONS 110 ROBERT TIMMONS 109 ERNEST STAPLES SR 108 BYRON CONSTANCE 108 ALFRED RATHBUN 107 WILLIAM BUSHALL JR 107 A CALVERT 107 JOHNKIME 107 KELLIE SALSBURY 106 MICHAEL ISEMAN 106 MONAOLSEN 106 THOMASOLSEN 106 SAMUEL STONE 106 JOHNTOOLE 105 VICTOR PONTE 104 PAUL CIPAR 104 DAVID THOMPSON 103 JOHN MCFADDEN 103 BENJAMIN PHILHOWER 103 SHERI PHILHOWER 103 BILL STOCK JR 103 MARTHA STOCK 102 GARY DYER 101 EDWARD GARBIN 101 TEDLAWSON 101 ROY STEPHENS JR 101 CLINT STOTT 100 JACK HARTLEY 100 PETER HULL 100 AARON KONECKY 100 DONNA LANDERS 100 GLEN LANDERS 100 DONSEPANSKI 99 CATHEY -

Nicholas Owen

Saint Nicholas Owen Born: Oxfordshire The son of a carpenter, Nicholas was raised in a family dedicated to the Catholic Church and followed his father’s trade. One of his brothers became a printer of Catholic literature and two were ordained priests. Nicholas worked with Edmund Campion, Father John Gerard and Father Henry Garnet, Superior of the English Jesuits from 1587 – 1594. Sometimes using the pseudonym John Owen; his short stature led to the nickname Little John. He spent over twenty-five years using his skills in the construction of ‘priest- holes’, escape-routes and some annexes for Mass. In order to keep his building-work secret, most was carried out at night, his presence explained by the daylight role as carpenter and mason. Early examples of his work exist at Oxburgh in East Anglia, Braddocks and Sawston. There are over a hundred examples of his work throughout central England. He built around a dozen hiding-places for Thomas Habington’s household at Hindlip Hall, Worcestershire; including that which Owen himself used prior to his capture. The authorities were aware the hiding- places existed, but neither their extent nor who constructed them. Nicholas did not have a formal novitiate, but having received instruction, he became a Jesuit Brother in 1577. In 1581, when Father Edmund Campion was executed, Nicholas remonstrated with the authorities and was imprisoned but later released. He was re-arrested on 23 April 1594 with John Gerard and held in the Tower of London, from where managed to free himself. It is said that he later orchestrated the escape of Father Gerard. -

Edward Hasted the History and Topographical Survey of the County

Edward Hasted The history and topographical survey of the county of Kent, second edition, volume 6 Canterbury 1798 <i> THE HISTORY AND TOPOGRAPHICAL SURVEY OF THE COUNTY OF KENT. CONTAINING THE ANTIENT AND PRESENT STATE OF IT, CIVIL AND ECCLESIASTICAL; COLLECTED FROM PUBLIC RECORDS, AND OTHER AUTHORITIES: ILLUSTRATED WITH MAPS, VIEWS, ANTIQUITIES, &c. THE SECOND EDITION, IMPROVED, CORRECTED, AND CONTINUED TO THE PRESENT TIME. By EDWARD HASTED, Esq. F. R. S. and S. A. LATE OF CANTERBURY. Ex his omnibus, longe sunt humanissimi qui Cantium incolunt. Fortes creantur fortibus et bonis, Nec imbellem feroces progenerant. VOLUME VI. CANTERBURY PRINTED BY W. BRISTOW, ON THE PARADE. M.DCC.XCVIII. <ii> <blank> <iii> TO THOMAS ASTLE, ESQ. F. R. S. AND F. S. A. ONE OF THE TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM, KEEPER OF THE RECORDS IN THE TOWER, &c. &c. SIR, THOUGH it is certainly a presumption in me to offer this Volume to your notice, yet the many years I have been in the habit of friendship with you, as= sures me, that you will receive it, not for the worth of it, but as a mark of my grateful respect and esteem, and the more so I hope, as to you I am indebted for my first rudiments of antiquarian learning. You, Sir, first taught me those rudiments, and to your kind auspices since, I owe all I have attained to in them; for your eminence in the republic of letters, so long iv established by your justly esteemed and learned pub= lications, is such, as few have equalled, and none have surpassed; your distinguished knowledge in the va= rious records of the History of this County, as well as of the diplomatique papers of the State, has justly entitled you, through his Majesty’s judicious choice, in preference to all others, to preside over the reposi= tories, where those archives are kept, which during the time you have been entrusted with them, you have filled to the universal benefit and satisfaction of every one. -

Planning Guide for Funeral Liturgies at Saint Joseph’S Church

Planning Guide for Funeral Liturgies at Saint Joseph’s Church _____________, 20__ – Funeral or Memorial Liturgy for the Soul of __________________________ (Month and Day) (Year) (Full Name of Deceased) The Funeral Liturgy is the central liturgical celebration of the Christian community for the deceased. There are two forms of the Funeral Liturgy: the Funeral Mass and the Funeral Liturgy outside Mass. During the Funeral Liturgy the community gathers with the family and friends of the deceased to give praise and thanks to God for Christ’s victory over sin and death, to commend the deceased to God’s tender mercy and compassion, and to seek strength in the proclamation of the paschal mystery. The Pastor or another designated minister will assist the family in understanding this planning guide and selecting readings and music appropriate for the Funeral or Memorial Liturgy. General guidelines for music in Eucharistic celebrations apply equally to the Funeral or Memorial Liturgy. The prayerful participation of the assembly—whether in silence or in song—affirms the value of praying for the soul of the deceased and gives strength and consolation to them. Sacred music is an integral part to the celebration of the Funeral Liturgy. The selection of music must be liturgical and express our Christian belief in the gift of the resurrection. Religious hymns should speak to the mysteries of our Faith regarding death and resurrection. While popular music may warm the hearts of those who are left behind, it must never replace sacred music, and is not suitable for a Funeral Liturgy. Such music is better suited to be played during the visitation or during a luncheon following Mass, if applicable. -

Suggestions for Prayers and Readings to Assist Families and Friends to Prepare the Catholic Requiem Mass

Suggestions for Prayers and Readings To assist families and friends To prepare the Catholic Requiem Mass This workbook will enable you to prepare an Order of Service for Requiem and choose from the Church’s readings and prayers. In this way you can be closer in spirit with your loved one who has died. Please follow the simple instructions inside. Another useful resource: “Life is changed not Ended”. A Workbook for preparing a Catholic Funeral. The Brisbane Liturgical Commission (your Parish will have it) FUNERAL LITURGY 1 ORDER OF SERVICE REQUIUM MASS FINAL COMMENDATION AND FAREWELL Gathering Song Words of Remembrance (if desired – can also INTRODUCTORY RITES take place before the Introductory Rites) Lighting of the Paschal Candle Recessional Hymn Sprinkling of the Holy Water Placing of the White Pall PRAYERS (without Mass) Placing of Flowers/Christian Symbols Gathering Hymn Opening Prayer INTRODUCTORY RITES Lighting of the Paschal Candle LITURGY OF THE WORD Sprinkling of the Holy Water Reading 1 Placing of the White Pall Psalm – usually sung Placing of Flowers/Christian Symbols Reading 2 (if required) Opening Prayer Verse before Gospel – sung (If not sung, then omitted) LITURGY OF THE WORD Gospel Reading 1 Homily Psalm – usually sung Prayer of the Faithful Reading 2 (if required) Verse before Gospel – sung LITURGY OF THE EUCHARIST (If not sung, then omitted) Procession of Gifts Gospel Preparation of Gifts Homily Eucharistic Prayer Prayer of the Faithful Communion Rite Thanksgiving Hymn FINAL COMMENDATION AND FAREWELL Words of Remembrance (if desired - can also take place before the Introductory Rites) Recessional Hymn FUNERAL LITURGY 2 ORDER OF SERVICE LITURGY OF THE WORD (see pages: 3-26) FIRST READING From 1 to 11 (Old Testament Readings) No. -

WRAP THESIS Shilliam 1986.Pdf

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/34806 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. FOREIGN INFLUENCES ON AND INNOVATION IN ENGLISH TOMB SCULPTURE IN THE FIRST HALF OF THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY by Nicola Jane Shilliam B.A. (Warwick) Ph.D. dissertation Warwick University History of Art September 1986 SUMMARY This study is an investigation of stylistic and iconographic innovation in English tomb sculpture from the accession of King Henry VIII through the first half of the sixteenth century, a period during which Tudor society and Tudor art were in transition as a result of greater interaction with continental Europe. The form of the tomb was moulded by contemporary cultural, temporal and spiritual innovations, as well as by the force of artistic personalities and the directives of patrons. Conversely, tomb sculpture is an inherently conservative art, and old traditions and practices were resistant to innovation. The early chapters examine different means of change as illustrated by a particular group of tombs. The most direct innovations were introduced by the royal tombs by Pietro Torrigiano in Westminster Abbey. The function of Italian merchants in England as intermediaries between Italian artists and English patrons is considered. Italian artists also introduced terracotta to England. -

By Hilda Plant

r' by Hilda Plant - ■■■ - s teitetrfs I o GERARD I ! by Hilda Plant I DEPARTMENT OF LEISURE (Director of Leisure G. Swift, B.A. (Econ), MrSc.) ”’** WIGAN METROPOLITAN BOROUGH COUNCIL I ©The Archivist, Wigan Record Office. 1982 ISBN 0 9507822 1 1 Front Cover: GARSWOOD HALL, 1900. Back Cover: . Sir. JOHl^GFRARJD-in his first field dress as commanding officer in theTocaFb>anch of the Lancashire Hussars. (1848). Designed and Printed b^ihe Supplies Section of Wigan Metropolitan Borough-Council (Administration Department) FOREWORD I am very pleased to write a short foreword to this publication, not least because of the strong connections between the Gerard Family and the Ashton-in-Makerfield Library building. The Carnegie Library at Ashton-in-Makerfield was formally opened on Saturday, 1 7 th March, 1906. The new library was (and still is) an imposing structure standing at the junction of Wigan Road and Old Road. It was built at the cost of£5,843, defrayed by Mr. Andrew Carnegie, on one of the most valuable sites in the district, generously given by Lord Gerard, who performed the opening ceremony. This booklet has been researched and written by a local resident, Miss H. Plant, and arose out of a lecture, which she gave to celebrate the 75th Anniversary of the opening of the library. I should like to record my personal thanks for her hard work in producing a fascinating account of the Gerard Family. F. Howard Chief Librarian & Curator, Wigan Metropolitan Borough p;--- - ;; ."H.. •> ■ T* J Band of the Lancashire Hussars. Bandmaster Mr. THOMAS BATTLE Y- Jubilee of the Regiment, 1898. -

Report To: Housing & City Support

Agenda Item 09 Report PC20/21-01 Report to Planning Committee Date 9 July 2020 By Director of Planning Local Authority Chichester District Council Application Number SDNP/20/01693/FUL Applicant Mr Mike Ruddock Application Construction of 12 treehouses to provide tourism accommodation across 2 woodland sites within the estate (5 x 1 bedroom units at Lodge Wood and 7 x 1 bedroom units at High Field Copse), access and parking, cycle storage, drainage and biodiversity enhancements and woodland management. Address Cowdray Park, A272 Easebourne St to Heath End Lane, Easebourne, West Sussex Recommendation: That planning permission be granted subject to the conditions set out in paragraph 10.1 of the report. Executive Summary The applicant seeks permission for the erection of 12 treehouses across two woodland sites within the Cowdray Estate to provide sustainable tourist accommodation within close proximity of Midhurst and public rights of way. The application follows the refusal of a previous scheme for 10 treehouses on one of the proposed sites (Lodge Wood) due to the size and scale of development and the harm deriving from the imposition of a suburban form of development on the historic woodland character; and associated impacts on biodiversity and priority habitat (see committee report and meeting minutes appended at Appendices 2 and 3). The current scheme has been subject to collaborative working between the applicant’s design team and specialist officers and as a result is considered to be a fully landscape-led proposal. The scheme would conserve and enhance the unique heritage, woodland and ecological character of each site, whilst also accruing significant benefits that would align with the Second Purpose and Duty of the National Park, including the provision of tourist accommodation, opportunities for the understanding and enjoyment of the National Park’s special qualities, and benefitting the local economy. -

Persons Index

Architectural History Vol. 1-46 INDEX OF PERSONS Note: A list of architects and others known to have used Coade stone is included in 28 91-2n.2. Membership of this list is indicated below by [c] following the name and profession. A list of architects working in Leeds between 1800 & 1850 is included in 38 188; these architects are marked by [L]. A table of architects attending meetings in 1834 to establish the Institute of British Architects appears on 39 79: these architects are marked by [I]. A list of honorary & corresponding members of the IBA is given on 39 100-01; these members are marked by [H]. A list of published country-house inventories between 1488 & 1644 is given in 41 24-8; owners, testators &c are marked below with [inv] and are listed separately in the Index of Topics. A Aalto, Alvar (architect), 39 189, 192; Turku, Turun Sanomat, 39 126 Abadie, Paul (architect & vandal), 46 195, 224n.64; Angoulême, cath. (rest.), 46 223nn.61-2, Hôtel de Ville, 46 223n.61-2, St Pierre (rest.), 46 224n.63; Cahors cath (rest.), 46 224n.63; Périgueux, St Front (rest.), 46 192, 198, 224n.64 Abbey, Edwin (painter), 34 208 Abbott, John I (stuccoist), 41 49 Abbott, John II (stuccoist): ‘The Sources of John Abbott’s Pattern Book’ (Bath), 41 49-66* Abdallah, Emir of Transjordan, 43 289 Abell, Thornton (architect), 33 173 Abercorn, 8th Earl of (of Duddingston), 29 181; Lady (of Cavendish Sq, London), 37 72 Abercrombie, Sir Patrick (town planner & teacher), 24 104-5, 30 156, 34 209, 46 284, 286-8; professor of town planning, Univ. -

News Release

NEWS RELEASE FOURTH STREET AT CONSTITUTION AVENUE NW WASHINGTON DC 20565 . 737-4215/842-6353 EXHBITION FACT SHEET Title; THE TREASURE HOUSES OF BRITAIN: FIVE HUNDRED YEARS OF PRIVATE PATRONAGE AND ART COLLECTING Patrons: Their Royal Highnesses The Prince and Princess of Wales Dates; November 3, 1985 through March 16, 1986, exactly one week later than previously announced. (This exhibition will not travel. Loans from houses open to view are expected to remain in place until the late summer of 1985 and to be returned before many of the houses open for their visitors in the spring of 1986.) Credits; This exhibition is made possible by a generous grant from the Ford Motor Company. The exhibition was organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, in collaboration v\n.th the British Council and is supported by indemnities from Her Majesty's Treasury and the U.S. Federal Council on the Arts and Humanities. Further British assistance was supplied by the National Trust and the Historic Houses Association. History of the exhibition; The suggestion that the National Gallery of Art consider holding a major exhibition devoted to British art was made by the British Council in 1979. J. Carter Brown, Director of the National Gallery, responded with the idea of an exhibition on the British Country House as a "vessel of civilization," bringing together works of art illustrating the extraordinary achievement of collecting and patronage throughout Britain over the past five hundred years. As this concept carried with it the additional, contemporary advantage of stimulating greater interest in and support of those houses open to public viewing, it was enthusiastically endorsed by the late Lord Howard of Henderskelfe, then-Chairman of the Historic Houses Association, Julian Andrews, Director of the Fine Arts Department of the British Council, and Lord Gibson, Chairman of the National Trust. -

Tstog of Or 6Ttr4* Anor of Ratigan

Thank you for buying from Flatcapsandbonnets.com Click here to revisit THE • tstog of Or 6ttr4* anor of ratigan IN THE COUNTY OF LANCASTER. BY THE HONOURABLE AND REVEREND GEORGE T. 0. BRIDGEMAN, Rotor of Wigan, Honorary Canon of Liverpool, and Chaplain in Ordinary to the Queen. (AUTHOR OF "A HISTORY OF THE PRINCES OF SOUTH WALES," ETC.) PART II. PRINTEDwww.flatcapsandbonnets.com FOR THE CH 1.71'HAM SOCIETY. 1889. Thank you for buying from Flatcapsandbonnets.com Click here to revisit 'tam of die cpurcl) ant) manor of Etligatt. PART II. OHN BRIDGEMAN was admitted to the rectory of Wigan on the 21st of January, 1615-16. JHe was the eldest son of Mr. Thomas Bridgeman of Greenway, otherwise called Spyre Park, near Exeter, in the county of Devon, and grandson of Mr. Edward Bridgeman, sheriff of the city and county of Exeter for the year 1562-3.1 John Bridgeman was born at Exeter, in Cookrow Street, and christened at the church of St. Petrok's in that city, in the paro- chial register of which is the following entry : " the seconde of November, A.D. 1597, John Bridgman, the son of Thomas Bridgman, was baptized." '1 Bishop John Bridgeman is rightly described by Sir Peter Leycester as the son of Mr. Thomas Bridgeman of Greenway, though Ormerod, in his History of Cheshire, who takes Leycester's Historical Antiquities as the groundwork for his History, erro- neously calls him the son of Edward Bridgeman, and Ormerod's mistake has been repeated by his later editor (Helsby's ed.