Aberystwyth University Robert Gwyn and Robert Persons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

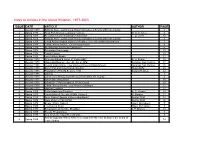

Clwyd Historian Index to Articles Issue 1 1977

Index to Articles in the Clwyd Historian, 1977-2005 ISSUE DATE ARTICLE AUTHOR PAGE 1 Autumn 1977 Editorial Note - List of Local History Societies & Events within the County 1 2 Spring 1978 Rhyn Park Roman Legionary Fortress G. D. B Jones 5 2 Spring 1978 All Saints Church at Llangar in Edeirnion T. O. Jones 10 2 Spring 1978 Editorial Note - List of Local History Societies & Events within the County 1 2 Spring 1978 Clwyd Archaeological Volunteer Register - Greenfield Mills Excavations 7 2 Spring 1978 Clwyd Library Service - Oral History Project 8 2 Spring 1978 An Historical Society for Edeyrnion? 9 2 Spring 1978 Recording Graveyards 10 2 Spring 1978 Family History 10 2 Spring 1978 Local History Books 11 3 Autumn 1978 Who was Edward Jones of Wepre Hall? D. G. Evans 15 3 Autumn 1978 Notes and Queries - Aer, Air, Ayr or Offa? Goronwy Alun Hughes 17 3 Autumn 1978 Recent Publications - Lles Cymru articles of Clwyd Interest Goronwy Alun Hughes 26 3 Autumn 1978 Bryn Y Pys and Gwernhaled, Overton Helen Duffy 28 3 Autumn 1978 Population of Flint M.B. since 1891 Zuzana Hughes 22 3 Autumn 1978 Editorial 1 3 Autumn 1978 List of Local History Societies & Events within the County 2 3 Autumn 1978 Information Requested 19 3 Autumn 1978 Exhibition of Photographs at Theatr Clwyd 20 3 Autumn 1978 Clwyd Library Service Local History Catalogue 21 3 Autumn 1978 Harvest Customs 21 4 Spring 1979 Puffin Island and Flintshire A. G. Veysey 19 4 Spring 1979 Excavations at Greenfield Mills, Holywell D. Morgan 11 4 Spring 1979 Does Rossett Appear in Domesday Book? Derrick Pratt 13 4 Spring 1979 Point of Ayr or Point Offa? Derrick Pratt 16 4 Spring 1979 Beware Place Names! Hywel Wyn Owen 8 4 Spring 1979 The Roman Road Hywel Wyn Owen 9 4 Spring 1979 Excavations at Hendre, Rhuddlan J. -

The Martyrology of the Monastery of the Ascension

The Martyrology of the Monastery of the Ascension Introduction History of Martyrologies The Martyrology is an official liturgical book of the Catholic Church. The official Latin version of the Martyrology contains a short liturgical service the daily reading of the Martyrology’s list of saints for each day. The oldest surviving martyologies are the lists of martyrs and bishops from the fourth-century Roman Church. The martyrology wrongly attributed to St. Jerome was written in Ital in the second half of the fifth century, but all the surviving versions of it come from Gaul. It is a simple martyrology, which lists the name of the saint and the date and place of death of the saint. Historical martyrologies give a brief history of the saints. In the eighth and ninth centuries, St. Bede, Rhabanus Maurus, and Usuard all wrote historical martyrologies. The Roman Martyrology, based primarily on Usuard’s, was first published in 1583, and the edition of 1584 was made normative in the Roman rite by Gregory XIII. The post-Vatican II revision appeared first in 2001. A revision that corrected typographical errors and added 117 people canonized by Pope John Paul II between 2001 and 2004, appeared in 2005.1 The Purpose and Principles of This Martyology The primary purpose of this martyrology is to provide an historically accurate text for liturgical use at the monastery, where each day after noon prayer it is customary to read the martyrology for the following day. Some things in this martyrology are specific to the Monastery of the Ascension: namesdays of the members of the community, anniversaries of members of the community who have died, a few references to specific events or saints of local interest. -

The Holy Maid of Wales: Visions, Imposture and Catholicism in Elizabethan Britain

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo 1 The Holy Maid of Wales: Visions, Imposture and Catholicism in Elizabethan Britain Alexandra Walsham (University of Cambridge) Abstract: This article explores the case of Elizabeth Orton of Overton in Flintshire, a young girl who experienced two ecstatic visions in February and March 1581 and was later exposed as a fraud. First, it uses this intriguing incident to illuminate the precarious stability of the Elizabethan polity at a moment of acute political crisis, when the fate of the Reformation itself seemed to be balanced on a knife edge. It contends that religious developments in north Wales and the Marches were far more significant than has previously been recognised and investigates how far it was inflected by Welsh patriotism. Secondly, it focuses attention on the rhetorical strategies by which Elizabeth Orton was discredited – on the modes of argument that were utilised in the ensuing contest about her own authenticity and about the truth of the Catholic religion. Setting aside the question of whether or not she was guilty of faking her trances and revelations, it suggests that the incident sheds fresh light on the nature and evolution of the entangled concepts of the imposture, hypocrisy and fraud. It shows how anxiety about the status and source of Elizabeth’s ecstatic experiences converged with intense concern about a second species of deceit and dissimulation: religious conformity. 2 At 8pm on the feast of Candlemas 1581 a thirteen-year-old girl from Overton in Flintshire who was sitting by the fireside in her father’s house suddenly began to weep.1 She fell down on her knees in front of her stepmother, sobbing and sighing that her time was appointed, and begging the forgiveness of any that she had offended. -

Eagle 1971 Lent

THE EAGLE A MAGAZIN E SUP PORTED BY MEMBERS OF ' ST J OHN S COLLEGE, CAM BRIDGE FO R SUBSC R IBERS ONLY J ANUAR Y 1971 Editorial page 86 Saints Richard Gwyn and Philip Howard 0' Kenneth Snipes 87 Letter to the Editor 89 Is St John's Christianity Christian? 0' GottJried Emsiin 90 Living in Provence 0' TOJ'!)' Wiiiiams 92 A Dust Street 0' Andrew Duff 94 The Making of Desmond Hackett 0' Sean lVIagee 95 Some Reminiscences of Alfred Marshall 0' c. W. Guiiiebaud 97 Reviews 100 Poems 0': John Eisberg, Graham HaruJood, Steve Briauit, Charles Reid-Dick, Vivian Bazaigette, Caius J\;lartius College Chronicle College Notes Front Cover: New Court and Cellars �y David Thistiethzvaite Editorial Committee: Dr LINEHAN (Senior Editor), Mr MACIN TOSH (Treasurer), GRAHAM HARDING (junior Editor), DAVID THISTLETHWAITE (Art Editor), JOHN ELSBER G, K. C. B. HUT CHESON , SEAN MAGEE, IAN THOR PE. All contributions for the next issue of the Magazine should be sent to the Editors, The Eagie, St John's College. in future; but their waking hours will certainly be that much duller. We wish him Editorial well, nonetbeless, for he still has thousands of runs in him and is eminently qualified to be a neighbour of that other Trinity College, where, doubtless, he will discover ' I DON T really like editorials. Look at the national papers; some sit on the fence, try just as many indications as he did here of the Absurdity of It All. ing to protect the danger spots with 'Asquithian liberalism', others defiantly wave P. -

Ordo-2021.Pdf

INTRODUCTION I THE CALENDAR The Plymouth Ordo is based on the General Calendar of the Church, the approved National Calendar for England, and the approved Calendar proper for the Diocese of Plymouth. II MOVABLE FEASTS and Weekday Holydays of Obligation First Sunday of Advent 29th November 2020 Immaculate Conception 8th December (Tuesday) The Nativity of the Lord 25th December (Friday) The Holy Family of Jesus, Mary and Joseph 27th December (Sunday) Mary, Mother of God 1st January 2021 (Friday) 2nd Sunday after the Nativity 3rd January The Epiphany 6th January (Wednesday) The Baptism of the Lord 10th January (Sunday) Ash Wednesday 17th February Easter Sunday 4th April The Ascension of the Lord 13th May (Thursday) Pentecost Sunday 23rd May The Most Holy Body and Blood of Christ 6th June (Sunday) The Most Sacred Heart of Jesus 11th June (Friday) St Peter & St Paul 29th June (Tuesday) The Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary 15th August (Sunday) All Saints (transferred) 31st October (Sunday) Our Lord Jesus Christ, King of the Universe 21st November First Sunday of Advent 28th November The Nativity of the Lord 25th December (Saturday) The Holy Family of Jesus, Mary and Joseph 26th December (Sunday) III THE MASS MASS FOR THE PEOPLE is to be said on Sundays and Solemnities which are Holydays of Obligation. Canon 534: After a pastor has taken possession of his parish, he is obliged to apply the Mass for the people entrusted to him on each Sunday and Holy Day of Obligation in his diocese. If he is legitimately impeded from this celebration however, he is to apply it on the same days through another or on other days himself. -

To What Extent Was Catholicism in Wales Still

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs To what extent was Catholicism in Wales still prevalent during the Reformation period, from its inception in 1536 to the Gunpowder Plot of 1605? A discussion relating to families and martyrs Student Dissertation How to cite: Brodie, Pauline (2018). To what extent was Catholicism in Wales still prevalent during the Reformation period, from its inception in 1536 to the Gunpowder Plot of 1605? A discussion relating to families and martyrs. Student dissertation for The Open University module A329 The making of Welsh history. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2018 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Redacted Version of Record Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk “To what extent was Catholicism in Wales still prevalent during the Reformation period, from its inception in 1536 to the Gunpowder Plot of 1605? A discussion relating to families and martyrs.” Pauline Brodie May 2018 Contents Introduction Pages 1 - 4 Chapter One Pages 4 - 10 Chapter Two Pages 10 - 13 Chapter Three Pages 13 - 16 Conclusion Pages 16 - 17 Bibliography Page 18 - 23 Page 1 Introduction With the founding of the Church of England by Henry VIII, the Reformation period was one of great change and upheaval for both church and country. As the Reformation in Wales became a pivotal point in history both in terms of religion, and also in language, law and unity with England, it seems that the continuance of the Catholic faith had been diminished, and willingly overthrown by the Anglican Protestant Church (Bradshaw 1998, p74), and it is noted that in the Protestant faith, ‘crucially-public worship was Welsh’ (Suggett and White 2002 p53). -

Vagabonds and Minstrels in Sixteenth-Century Wales Vagabonds and Minstrels in Sixteenth-Century Wales Richard Suggett

Chapter 5 The spoken word6 Vagabonds and minstrels in sixteenth-century Wales Vagabonds and minstrels in sixteenth-century Wales Richard Suggett hroughout much of late medieval and early modern Europe, from TPoland and Russia in the east to Wales and Ireland in the west, itinerant minstrels entertained noble and plebeian audiences. Wandering entertainers may well have provided (as Burke has suggested) one of the unifying elements within European popular culture. A pan-European tradition of minstrelsy, crossing social and cultural boundaries, is an appealing idea, but the differ- ences as well as the similarities between minstrels need to be appreciated. A diversity of vernacular terms for minstrels conveyed status differences as well as different performance skills among the entertainers. Some perform- ance genres travelled better than others. Low-status physical performers – acrobats, jugglers and dancers – probably moved more easily between different language and cultural groupings than verbal performers, who might have high status within their own speech communities. Traditions of minstrelsy that gave high prestige to oral poetry and the music that accompanied recitation, and were tightly related to internal social structures, may have been important for defining local solidarities but might be regarded externally as ludicrously unmusical. However it is clear that, despite a diversity of performance genres, minstrels considered as a professional occupational grouping shared recognizably similar historical experiences of itinerancy, episodic persecution, and attempts at self-protection through membership of fraternities. Minstrels were culturally important as entertainers, social com- mentators and remembrancers but their mobility, communication in oral rather than written genres, and increasingly marginal position in the sixteenth century have made entertainers particularly elusive for the historian. -

Worship the Lord

St. John the Beloved Catholic Church in McLean, Virginia October 25, 2020 Worship the Lord Mass Intentions Remember in Prayer Monday, October 26 Patricia Ahern Diana Meisel Weekday Frank Bohan Bonnie Moran 6:30 Richard Straub † Carmel Broadfoot Veronica Nowakowski 9:00 Special Intention John Cartelli Anita Oliveira Victoria Grace Czarniecki Emelinda Oliveira 8:00 Souls in Purgatory Kerry Darby Sally O’Malley Tuesday, October 27 Tara Flanagan-Koenig John Peterson Weekday Alexa Frisbie Mary Pistorino Reilly 6:30 Gary Arlen Broomes Susan Glover Shelby Rogers Francisca Grego Thomas Rosa 9:00 Hugo Valdes † Arnold L. Harrington III Murielle Rozier-Francoville Wednesday, October 28 Colleen Hodgdon Avery Schaeffer Sts. Simon and Jude, Apostles David Johnson Merle Shannon 6:30 Richard Stier † Mark Johnson Gloribeth Smith Christopher Katz Glenn Snyder 9:00 William Kremidas † Margaret Kemp Bill Sullivan Thursday, October 29 Dorothy Kottler Brian Turner Weekday Sue Malone Ana Vera 6:30 James Michael Kazunas † Carmella Manetti Mary Warchot Cristina Marques Marie Wysolmerski 9:00 Fredda Coomes Richard Meade Friday, October 30 Weekday Eternal Rest Grant Unto Them, O Lord 6:30 Nazhet Ol-Molouk Safi-Shahi † † CAROLYN STEINHOFF † 9:00 Collin, Leah and Finn † ARLENE ZELEZNIKAR † Saturday, October 31 Weekday † RICHARD DECORPS † 8:15 Cynthia Cotter † 5:00 The Perlowski Family † Sunday, November 1 Holy Father’s Prayer Intentions All Saints October—The Laity's Mission in the Church 7:30 James Michael Kazunas † We pray that by the virtue of baptism, the laity, 9:00 Ludmilla Kukuvka † especially women, may participate more in areas of 10:30 People of the Parish responsibility in the Church. -

28Th Sunday of the Year 2020

Recently died Parish Contacts The Priory 67 Talbot St. Canton, Cardiff Holy Family & St Mary of the Angels Please pray for the eternal repose of the tel: (029) 20 230 492 following: Parishes of St. Mary’s and Holy Family Keyston Rd, Fairwater CF5 3NP Kings Rd, Canton CF11 9BX new email address is: [email protected] Canon Peter Collins 11th-18th October 2020 28th Sunday of the Year Cycle A Mr Daniel Thompson – The e-mail: [email protected] Holy Family Masses Funeral Mass will be celebrated on Fr Nick Williams Readings for 28th Sunday of the Year Monday 12th October at 12.00.pm in Sunday: 28th Sunday of the Year (11th October) e-mail: [email protected] Isaiah 25:6-10. St Mary’s. Deacon Professor Maurice Scanlon For some religious-philosophical-cultural traditions, history is merely one long 6pm Vigil Mass Geraldine Luxton e-mail: [email protected] decline from some previous golden age or merely an endless cyclical repetition 11am May Davet of established patterns which cannot truly be altered. The Hebraeo-Christian Mr Danny O’Driscoll, formerly of tel (029) 2021 2651 tradition teaches something different, something distinct. Revelation is pur- Sunday: 29th Sunday of the Year (18th October) Holy Family parish, died recently at his home in Website: cardiffwestcatholics.org.uk poseful, it is providential. God is the source of world history and its end. God 6pm Vigil Mass For the People of the Parish reveals himself not as a distant figure but as one engaged with his chosen peo- Australia. -

Government of the People Not the Politicians by the People Not the Pressure Groups for the People All of Us

ine tony martyrs /ire Canonized POLITICAL ADVERTISEMENT By RONALD PAPPERT DAMICO SAYS: The Forty Martyrs of Eng- land'and Wales were canonized last Sunday by Pope Paul VI. THE ABORTION LAW The largest group of saints ever canonized, they represent IS FAR TOO LIBERAL. men and women of many dif ferent ages and occupations IT MUST BE AMEND . who were executed between; the years 1535 and 1679.' ED. Many disapproved of the canonization as being detrimen VOTE NOV. 3 tal to the ecumenical spirit, since they were martyred dur JOHN ing the English Protestant Eeformation, These 40 martyrs, ASSEMBLYMAN however, were selected 10 years ago from a long list and are DAMICO-GREECE & N. WEST CITY known for their spirit of char i ity and holiness in the face of unjust, legal persecution. Among the many laws en forced in 16th Century England against Catholics, one of the most damaging,was enacted by Scene from painting of "40 Martyrs". Queen 'Elizabeth I in 1585 ^ 'EVERGREEN NURSERY Tr which made it high treason to being found today. He spoke life to God rather than betray be a priest and a felony to little, prayed much, worked the trust that his special voca NOW OPEN 7 DAYS assist one, both punishable by hard, and in the end gave his tion demanded. death. Many of these martyrs, See and Buy Where it Grows were priests and laymen who 3446 Mt. Read Blvd. 865-7813 carried out an extensive under 8 Mooney Seniors ground apostolate in violation Christie Named of these laws. Awarded Letters SPECIAL OFFER Famous members of the To Cancer Post Letters of commendation group include Blessed Cuthbert from the National Merit Schol Mayne, secular priest; Blessed R. -

Tudor Religious Changes

TUDOR RELIGIOUS CHANGES KEY STAGE 3 In the sixteenth century Britain and Europe experienced a hugely significant and far-reaching challenge to existing ideas: the Reformation. This was a religious movement which clashed with the powerful institution of the Catholic Church and challenged people’s beliefs about God and the world. A new strand of Christian faith emerged from the Reformation called Protestantism. Protestants saw the old Catholic faith and those who practised it as their enemies. Catholics likewise viewed Protestants as heretics tearing down centuries of tradition. The Reformation affected how ordinary people worshipped in their local churches but also how they thought about their place in society. Across Europe it also threatened kings and queens, toppled governments and sparked rebellions. Much of the blood spilled in sixteenth-century Europe was shed because of religion and battles over the Reformation. As all of this shows, religion was a much more important part of this society than is the case in most western countries today. Everyone, from monarchs to peasants, saw religion as a crucial feature of their lives. Imagine, then, the huge challenges presented by King Henry VIII’s decision in the 1530s to break with the Catholic Church and set England and Wales on the road to Protestantism. This struck directly at the religion which had been at the core of Welsh life and identity for a thousand years. Beloved beliefs and practices were forbidden. The worship of cherished local saints and pilgrimages to important shrines were stopped. Churches changed radically as colourful paintings were blotted out and beautiful images (like stained glass) and statues were vandalised or destroyed. -

11Th October 2020 Twenty-Eighth Sunday in Ordinary Time

Weekend 10th – 11th October 2020 Twenty-Eighth Sunday in Ordinary Time List of Topics in this newsletter – click on the topic list to get to the relevant section Mass Times and Intentions week beginning 11th October 2020 ............................................ 2 Occasions when the Church is open for Mass ...................................................................... 3 If you wish to attend Mass .................................................................................................... 3 Mass Times .......................................................................................................................... 4 October – The Month of the Holy Rosary.............................................................................. 5 Exposition of the Blessed Sacrament ................................................................................... 5 Polish Masses ....................................................................................................................... 5 Live Streaming ...................................................................................................................... 5 Dial for Mass ......................................................................................................................... 5 Quote of the Week ................................................................................................................ 6 Rest in Peace ......................................................................................................................