Newsletter of May 7, 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pembrokeshire Fungus Recorder Issue 2/2019

Pembrokeshire Fungus Recorder Issue 2/2019 Published biannually by the Pembrokeshire Fungus Recording Network www.pembsfungi.org.uk Contents 1. Contents & Editorial 2. Fungus records 4. Events - Training day - Joint events 6. Pembrokeshire Nature Partnership 6. Illustrating waxcaps 7. Entoloma vezzenaense - new to Britain Editorial With the season well underway, time for a mid-term report. Rainfall (mm) Rainfall figures (courtesy of Orielton Field Study Centre) show that after a fairly average April-July rainfall, August and September were wetter than average: something that may explain a reasonably promising start to the waxcap-grassland season. This year has been a busy one for events - and in this issue we report on our training day in May which covered rusts and DNA-barcoding and two autumn field recording events which were run in conjunction with other groups. Our next issue will include reports on our UK Fungus Day event hosted at Orielton Field Centre together with other recent recording/traing events in which we have been involved. As we develop our expertise in DNA-barcoding techiques we are happy to consider in-house projects where we use barcoding to support the identification of cryptic species from particular fungus assemblages. Currently we are looking at chanterelles, at the suggestion of Adam Pollard-Powell, and will report on this, and our work on sand dune morels, in the next issue. David Harries October 2019 Records Fungal galls on plants June produced some interesting fungal plant pathogens with the County's second record for camellia galls (Exobasidium camelliae) (pictured right) reported by Robin Taylor from his garden in Hayscastle. -

Noble Hardwoods Network

EUROPEAN FOREST GENETIC RESOURCES PROGRAMME (EUFORGEN) Noble Hardwoods Network Report of the second meeting 22-25 March 1997 Lourizan, Spain J. Turok, E. Collin, B. Demesure, G. Eriksson, J. Kleinschmit, M. Rusanen and R. Stephan, compilers ii NOBLE HARDWOODS NETWORK: SECOND MEETING The International Plant Genetic Resources Institute (IPGRl) is an autonomous international scientific organization, supported by the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). IPGRl's mandate is to advance the conservation and use of plant genetic resources for the benefit of present and future generations. IPGRl's headquarters is based in Rome, Italy, with offices in another 14 countries worldwide. It operates through three programmes: (1) the Plant Genetic Resources Programme, (2) the CGIAR Genetic Resources Support Programme, and (3) the International Network for the Improvement of Banana and Plantain (INIBAP). The international status of IPGRl is conferred under an Establishment Agreement which, by January 1998, had been signed and ratified by the Governments of Algeria, Australia, Belgium, Benin, Bolivia, Brazil, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chile, China, Congo, Costa Rica, Cote d'Ivoire, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Ecuador, Egypt, Greece, Guinea, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Iran, Israel, Italy, Jordan, Kenya, Malaysia, Mauritania, Morocco, Pakistan, Panama, Peru, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Senegal, Slovak Republic, Sudan, Switzerland, Syria, Tunisia, Turkey, Uganda and Ukraine. Financial support for the Research Agenda of -

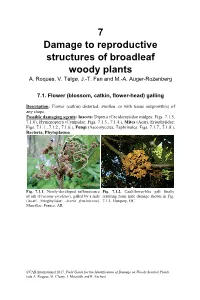

Field Guide for the Identification of Damage on Woody Sentinel Plants (Eds A

7 Damage to reproductive structures of broadleaf woody plants A. Roques, V. Talgø, J.-T. Fan and M.-A. Auger-Rozenberg 7.1. Flower (blossom, catkin, flower-head) galling Description: Flower (catkin) distorted, swollen, or with tissue outgrowth(s) of any shape. Possible damaging agents: Insects: Diptera (Cecidomyiidae midges: Figs. 7.1.5, 7.1.6), Hymenoptera (Cynipidae: Figs. 7.1.3., 7.1.4.), Mites (Acari, Eriophyiidae: Figs. 7.1.1., 7.1.2., 7.1.6.), Fungi (Ascomycetes, Taphrinales: Figs. 7.1.7., 7.1.8.), Bacteria, Phytoplasma. Fig. 7.1.1. Newly-developed inflorescence Fig. 7.1.2. Cauliflower-like gall finally of ash (Fraxinus excelsior), galled by a mite resulting from mite damage shown in Fig. (Acari, Eriophyiidae: Aceria fraxinivora). 7.1.1. Hungary, GC. Marcillac, France, AR. ©CAB International 2017. Field Guide for the Identification of Damage on Woody Sentinel Plants (eds A. Roques, M. Cleary, I. Matsiakh and R. Eschen) Damage to reproductive structures of broadleaf woody plants 71 Fig. 7.1.3. Berry-like gall on a male catkin Fig. 7.1.4. Male catkin of Quercus of oak (Quercus sp.) caused by a gall wasp myrtifoliae, deformed by a gall wasp (Hymenoptera, Cynipidae: Neuroterus (Hymenoptera, Cynipidae: Callirhytis quercusbaccarum). Hungary, GC. myrtifoliae). Florida, USA, GC. Fig. 7.1.5. Inflorescence of birch (Betula sp.) Fig. 7.1.6. Symmetrically swollen catkin of deformed by a gall midge (Diptera, hazelnut (Corylus sp.) caused by a gall Cecidomyiidae: Semudobia betulae). midge (Diptera, Cecidomyiidae: Contarinia Hungary, GC. coryli) or a gall mite (Acari Eriophyiidae: Phyllocoptes coryli). -

Species of Taphrina on Alnus in Slovakia

C zech m y co l. 47 (3), 1994 Species of Taphrina on Alnus in Slovakia Kamila Bacigálová Institute of Botany, Slovak Academy of Sciences, Dúbravská cesta 14, 842 23 Bratislava, Slovak Republic Bacigálová K. (1994): Species of Taphrina on Alnus in Slovakia. - Czech Mycol. 47: 223-236 New data are presented on the occurrence of Taphrina Fr. [T. alni (Berk, et Br.) Gjaerum, Tepiphylla (Sadeb.) Sacc., T. tosquinetii (Westend.) Magn. and T. sadebeckii Johans.) on Alnus Mill. (A. incana (L.) Moench, A. glutinosa (L.) Gaertn.], till now unknown in Slovakia. Brief characteristics as to biology, ecology and distribution of the mentioned fungi as well as their host plants are given together with the ecological characteristics of the new localities. Key words: Taphrina Fr., Alnus Mill., Slovakia, biology, ecology, distribution Bacigálová K. (1994): Druhy rodu Taphrina na hostitelských rastlinách rodu Alnus na Slovensku. - Czech Mycol. 47: 223-236 Sú opísané v rastlinných spoločenstvách na Slovensku doteraz všeobecne málo známe druhy fytopatogénnych húb rodu Taphrina Fr.: Taphrina alni (Berk, et Br.) Gjaerum - grmaník šištičiek jelše, Taphrina epiphylla (Sadeb.) Sacc. - grmaník vetvičiek jelše šedej, Taphrina tosquinetii (Westend.) Magn. - grmaník listov jelše lepkavej, Taphrina sadebeckii Johans. — grmaník listov jelše na druhoch rodu Alnus Mill.: Alnus glutinosa (L.) Gaertn., Alnus incana (L.) Moench). Autorka opisuje symptomy ochorenia na hostitelských rastlinách, anatomicko- morfologické charakteristiky húb, lokality ich výskytu a ich ekologické -

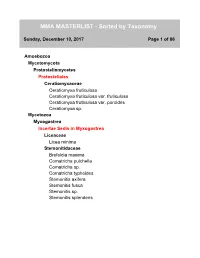

MMA MASTERLIST - Sorted by Taxonomy

MMA MASTERLIST - Sorted by Taxonomy Sunday, December 10, 2017 Page 1 of 86 Amoebozoa Mycetomycota Protosteliomycetes Protosteliales Ceratiomyxaceae Ceratiomyxa fruticulosa Ceratiomyxa fruticulosa var. fruticulosa Ceratiomyxa fruticulosa var. poroides Ceratiomyxa sp. Mycetozoa Myxogastrea Incertae Sedis in Myxogastrea Liceaceae Licea minima Stemonitidaceae Brefeldia maxima Comatricha pulchella Comatricha sp. Comatricha typhoides Stemonitis axifera Stemonitis fusca Stemonitis sp. Stemonitis splendens Chromista Oomycota Incertae Sedis in Oomycota Peronosporales Peronosporaceae Plasmopara viticola Pythiaceae Pythium deBaryanum Oomycetes Saprolegniales Saprolegniaceae Saprolegnia sp. Peronosporea Albuginales Albuginaceae Albugo candida Fungus Ascomycota Ascomycetes Boliniales Boliniaceae Camarops petersii Capnodiales Capnodiaceae Scorias spongiosa Diaporthales Gnomoniaceae Cryptodiaporthe corni Sydowiellaceae Stegophora ulmea Valsaceae Cryphonectria parasitica Valsella nigroannulata Elaphomycetales Elaphomycetaceae Elaphomyces granulatus Elaphomyces sp. Erysiphales Erysiphaceae Erysiphe aggregata Erysiphe cichoracearum Erysiphe polygoni Microsphaera extensa Phyllactinia guttata Podosphaera clandestina Uncinula adunca Uncinula necator Hysteriales Hysteriaceae Glonium stellatum Leotiales Bulgariaceae Crinula caliciiformis Crinula sp. Mycocaliciales Mycocaliciaceae Phaeocalicium polyporaeum Peltigerales Collemataceae Leptogium cyanescens Lobariaceae Sticta fimbriata Nephromataceae Nephroma helveticum Peltigeraceae Peltigera evansiana Peltigera -

Tarset and Greystead Biological Records

Tarset and Greystead Biological Records published by the Tarset Archive Group 2015 Foreword Tarset Archive Group is delighted to be able to present this consolidation of biological records held, for easy reference by anyone interested in our part of Northumberland. It is a parallel publication to the Archaeological and Historical Sites Atlas we first published in 2006, and the more recent Gazeteer which both augments the Atlas and catalogues each site in greater detail. Both sets of data are also being mapped onto GIS. We would like to thank everyone who has helped with and supported this project - in particular Neville Geddes, Planning and Environment manager, North England Forestry Commission, for his invaluable advice and generous guidance with the GIS mapping, as well as for giving us information about the archaeological sites in the forested areas for our Atlas revisions; Northumberland National Park and Tarset 2050 CIC for their all-important funding support, and of course Bill Burlton, who after years of sharing his expertise on our wildflower and tree projects and validating our work, agreed to take this commission and pull everything together, obtaining the use of ERIC’s data from which to select the records relevant to Tarset and Greystead. Even as we write we are aware that new records are being collected and sites confirmed, and that it is in the nature of these publications that they are out of date by the time you read them. But there is also value in taking snapshots of what is known at a particular point in time, without which we have no way of measuring change or recognising the hugely rich biodiversity of where we are fortunate enough to live. -

Index to Cecidology up to Vol. 31 (2016)

Index to Cecidology Up to Vol. 31 (2016) This index has been based on the contents of the papers rather than on their actual titles in order to facilitate the finding of papers on particular subjects. The figures following each entry are the year of publication, the volume and, in brackets, the number of the relevant issue. Aberbargoed Grasslands: report of 2011 field meeting 2012 27 (1) Aberrant Plantains 99 14(2) Acacia species galled by Fungi in India 2014 29(2) Acer gall mites (with illustrations) 2013 28(1) Acer galls: felt galls re-visited 2005 20(2) Acer saccharinum – possibly galled by Dasineura aceris new to Britain 2017 32(1) Acer seed midge 2009 24(1) Aceria anceps new to Ireland 2005 20 (1) Aceria geranii from North Wales 1999 14(2) Aceria heteronyx galling twigs of Norway Maple 2014 29(1) Aceria ilicis (gall mite) galling holm oak flowers in Brittany 1997 12(1) In Ireland 2010 25(1) Aceria mites on sycamore 2005 20(2) Aceria populi galling aspen in Scotland 2000 15(2) Aceria pterocaryae new to the British mite fauna 2008 23(2) Aceria rhodiolae galling roseroot 2013 28(1): 2016 31(1) Aceria rhodiolae in West Sutherland 2014 29(1) Aceria tristriata on Walnut 2007 22(2) Acericecis campestre sp. nov. on Field Maple 2004 19(2) Achillea ptarmica (sneezewort) galled by Macrosiphoniella millefolii 1993 8(2) Acorn galls on red oak 2014 29(1) Acorn stalks: peculiar elongation 2002 17(2) Aculops fuchsiae – a fuchsia-galling mite new to Britain 2008 23 (1) Aculus magnirostris new to Ireland 2005 20 (1) Acumyia acericola – the Acer seed -

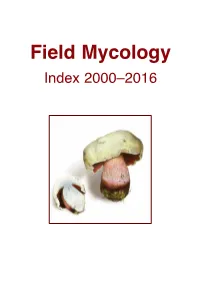

Field Mycology Index 2000 –2016 SPECIES INDEX 1

Field Mycology Index 2000 –2016 SPECIES INDEX 1 KEYS TO GENERA etc 12 AUTHOR INDEX 13 BOOK REVIEWS & CDs 15 GENERAL SUBJECT INDEX 17 Illustrations are all listed, but only a minority of Amanita pantherina 8(2):70 text references. Keys to genera are listed again, Amanita phalloides 1(2):B, 13(2):56 page 12. Amanita pini 11(1):33 Amanita rubescens (poroid) 6(4):138 Name, volume (part): page (F = Front cover, B = Amanita rubescens forma alba 12(1):11–12 Back cover) Amanita separata 4(4):134 Amanita simulans 10(1):19 SPECIES INDEX Amanita sp. 8(4):B A Amanita spadicea 4(4):135 Aegerita spp. 5(1):29 Amanita stenospora 4(4):131 Abortiporus biennis 16(4):138 Amanita strobiliformis 7(1):10 Agaricus arvensis 3(2):46 Amanita submembranacea 4(4):135 Agaricus bisporus 5(4):140 Amanita subnudipes 15(1):22 Agaricus bohusii 8(1):3, 12(1):29 Amanita virosa 14(4):135, 15(3):100, 17(4):F Agaricus bresadolanus 15(4):113 Annulohypoxylon cohaerens 9(3):101 Agaricus depauperatus 5(4):115 Annulohypoxylon minutellum 9(3):101 Agaricus endoxanthus 13(2):38 Annulohypoxylon multiforme 9(1):5, 9(3):102 Agaricus langei 5(4):115 Anthracoidea scirpi 11(3):105–107 Agaricus moelleri 4(3):102, 103, 9(1):27 Anthurus – see Clathrus Agaricus phaeolepidotus 5(4):114, 9(1):26 Antrodia carbonica 14(3):77–79 Agaricus pseudovillaticus 8(1):4 Antrodia pseudosinuosa 1(2):55 Agaricus rufotegulis 4(4):111. Antrodia ramentacea 2(2):46, 47, 7(3):88 Agaricus subrufescens 7(2):67 Antrodiella serpula 11(1):11 Agaricus xanthodermus 1(3):82, 14(3):75–76 Arcyria denudata 10(3):82 Agaricus xanthodermus var. -

Parasitic Microfungi of the Tatra Mountains. 1. Taphrinales

Polish Botanical Studies 50(2): 185–207, 2005 PARASITIC MICROFUNGI OF THE TATRA MOUNTAINS. 1. TAPHRINALES KAMILA BACIGÁLOVÁ, WIESŁAW MUŁENKO & AGATA WOŁCZAŃSKA Abstract. A list of species and the distribution of the members of Protomycetaceae and Taphrinaceae (Taphrinales, Ascomycota) in the Tatra Mts are given. Noted in the area were 20 species of fungi parasitizing 33 species of plants, including 4 species of the genus Protomyces Unger on 16 host plants, 3 species of the genus Protomycopsis Magn. on 4 species of host plants, and 13 species of the genus Taphrina Fr. on 14 species of host plant. Key words: Protomycetaceae, Taphrinaceae, Ascomycota, Western Carpathians, Tatra Mts, Slovakia, Poland Kamila Bacigálová, Institute of Botany, Slovak Academy of Sciences, Dúbravská cesta 14, SK-845 23, Bratislava, Slovakia; e-mail: [email protected] Wiesław Mułenko & Agata Wołczańska, Department of Botany and Mycology, Institute of Biology, Maria Curie-Skłodowska Uni- versity, Akademicka 19, PL-20-033 Lublin, Poland; e-mail: [email protected] INTRODUCTION Members of the Taphrinales are biotrophic fungi rosporus Unger on Aegopodium podagraria L., parasitizing ferns and higher plants. They are di- Prenčov, 12 Oct. 1886, leg. A. Kmeť, BRA), and morphic organisms with a saprobic yeast stage and later from the Spiš region, collected by Viktor Gre- a parasitic mycelial stage on plant hosts, causing schik [Taphrina alni (Berk. & Broome) Gjaerum characteristic morphological changes on infected on Alnus incana, Levoča, Aug. 1928, leg. V. Gre- plants: hypertrophy and hyperplasia of the infected schik, BRA]. Intense investigations began about tissues usually result in the formation of distinct 20 years ago, when a series of publications on the galls or swellings (Protomycetaceae), ‘leaf curl,’ distribution, ecology and taxonomy of these fungi ‘witches brooms,’ tongue-like outgrowths from in Slovakia came out (Bacigálová 1991, 1992, female catkins, leaf spots or deformed fruits (Ta- 1994a, b, c, 1997; Bacigálová et al. -

The Flora and Fauna of the Northwich Woodlands

The Flora and Fauna of the Northwich Woodlands Compiled by Paul M Hill Last updated: 23 rd August 2010 CONTENTS Plants 4 Mosses 8 Fungi 9 Bryophytes 10 Lichens 10 Beetles 11 Bees, Ants and Wasps 13 Sawflies 13 Parasitic / Gall Waps 14 True Bugs 14 Planthoppers and Aphids 14 Mayflies 14 Scorpianflies 15 Lacewings 15 Stoneflies 15 Caddisflies 15 Flies 15 Micro-moths 20 Butterflies 24 Macro-moths 24 Dragonflies and Damselflies 27 Earwigs 27 Grasshopper, Crickets and Groundhoppers 28 Amphipods 28 Wood and Water Louse 28 Spiders 28 Mites 29 Centipedes and Millipedes 29 Leeches 29 Snails and Slugs 30 Birds 31 Mammals 33 Amphibians and Reptiles 33 BOTANICAL Plants Equisetum arvense............. Field Horsetail Phleum bertolonii................ Smaller Cat's-tail Equisetum palustre............. Marsh Horsetail Phleum pratense ................ Timothy Equisetum sylvaticum......... Wood Horsetail Phragmites australis ........... Common Reed Larix decidua ..................... European Larch Poa annua.......................... Annual Meadow-grass Pinus nigra......................... Austrian Pine / Corsican Poa compressa .................. Flattened Meadow-grass Pine Poa pratensis ..................... Smooth Meadow-grass Pinus sylvestris .................. Scots Pine Poa humilis......................... Spreading Meadow-grass Taxus baccata.................... Yew Poa trivialis......................... Rough Meadow-grass Taxodium distichum ........... Swamp Cypress Puccinellia distans.............. Reflexed Saltmarsh-grass Ophioglossum vulgatum.... -

Kritische Untersuchungen Über Die Durch Taphrina-Arten

© Biodiversity Heritage Library, http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/; www.zobodat.at Kritische Untersuchungen über die durch Taphrina-Arten hervorgebrachten Baumkrankheiten. Von Prof. Dr. B. Sadebeck, Director des Botanischen Museums und Laboratoriums lüi* Waarenkundi zu Hamburg. (Arbeiten des Botanischen Museums. 1890.) Mit 5 Tafeln Abbildungen. © Biodiversity Heritage Library, http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/; www.zobodat.at © Biodiversity Heritage Library, http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/; www.zobodat.at Einleitung. • In meiner ersten Abhandlung über « l i < Pilzgruppe Taphrina, resp. Exoascus: „Untersuchungen über die Pilzgattung Exoascus und die durch dieselbe um Eam]jrarg hervorgerufenen Baumkrankheiten, diese Jahrbücher, I. I>d. Eamburg, 1884" hatte ich versucht, einerseits die Entwicklungsgeschichte dieser auch in pathologischer Beziehung interessanten Pilzgruppe vorläufig an zwei Beispielen klarzulegen, andererseits aber auch in der Vergleichung der Gestalt, Grösse und Entwicklung des Fruchtkörpers die Wege für eine genaue Bestimmung der Species zu finden. Bezüglich der letzteren kam es nicht darauf an, neue Arten aufzusuchen, als vielmehr sichere Anhalts- punkte zu gewinnen für die bei dieser Familie hervortretende Frage- stellung mich der Accomodationsfähigkeit dcv Pilzspecies für ver- schiedene Nährpflanzen, sowie im Einzelnen die pathologischen Eingriffe der Taphrina-Arten genauer zu studiren. Unter Zugrundelegung dieser Gesichtspunkte ist inzwischen eine 1 Anzahl von Abhandlungen ) erschienen, welche meine ersten An- gaben erweitert haben, namentlich mit Bezug auf diejenigen Species und Varietäten, welche ausserhalb des von mir untersuchten Gebietes i) W. Gr. Farlow. \. Provisio»al Host-Index of the fungi of the United Staates. Cambridge, August 1888. — C. Fisch. Ueber Exoascus Aceris Linie (Bot. Centralbl. Bd. XXII. L885. Nr. 17). — Derselbe, Ueber *die Pikgattung \ c yces (Botanische Zeitung, Jahrg. XL III). -

Cecidology 33.1 Page 5: Plant Galls at Brocks Hill Country Park Oadby Leicestershire (Chris Leach)

Cecidology 33.1 page 5: Plant Galls at Brocks Hill Country Park Oadby Leicestershire (Chris Leach) List of Gall causing species found in Brocks Hill Park 2003-2017 * species cited in the text Host Host (common name) Gall Gall causer Organism Comment Acer campestre Maple (Field/hedge) warty growth on twigs Aceria heteronyx a mite Acer campestre small rounded pustules, usually red Aceria myriadeum a mite Acer campestre rounded pustules usually 1-10 per leaf Aceria macrochela a mite Acer campestre small pimple on leaves, depression below Acericecis campestris a mite Acer campestre felt on underside of leaves Aceria eriobia a mite Acer campestre wrinkled leaves with thick veins Dasineura irregularis a midge Acer campestre pale blister in leaves Dasineura tympani* a midge a new comer, first seen 2015 Acer pseudoplatanus Sycamore small rounded pustules, usually red Aceria cephalonea a mite Acer pseudoplatanus felt on underside of leaves Aceria pseudoplatani a mite Aesculus hippocastanum Horse-chestnut tufts of hairs in angle of leaf veins Aculus hippocastani a mite Alnus glutinosa Alder felt with bulge above on leaves Acalitus brevitarsus a mite Alnus glutinosa bulges in vein angles Aceria nalepai a mite Alnus glutinosa small bulges scattered on leaves Eriophyes laevis a mite Alnus glutinosa leaf margin rolled Dasineura tortilis a midge Alnus glutinosa "tongues" emerging from female catkins Taphrina alni* a fungus Alnus glutinosa incurved, much enlarged leaves, brittle Taphrina tosquinetii a fungus Alnus glutinosa enlarged leaves, bright yellow