ATINER's Conference Paper Series MDT2015-1478

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rough Guide to Naples & the Amalfi Coast

HEK=> =K?:;I J>;HEK=>=K?:;je CVeaZh i]Z6bVaÒ8dVhi D7FB;IJ>;7C7B<?9E7IJ 7ZcZkZcid BdcYgV\dcZ 8{ejV HVc<^dg\^d 8VhZgiV HVciÉ6\ViV YZaHVcc^d YZ^<di^ HVciVBVg^V 8{ejVKiZgZ 8VhiZaKdaijgcd 8VhVaY^ Eg^cX^eZ 6g^Zcod / AV\dY^EVig^V BVg^\a^Vcd 6kZaa^cd 9WfeZ_Y^_de CdaV 8jbV CVeaZh AV\dY^;jhVgd Edoojda^ BiKZhjk^jh BZgXVidHVcHZkZg^cd EgX^YV :gXdaVcd Fecf[__ >hX]^V EdbeZ^ >hX]^V IdggZ6ccjco^ViV 8VhiZaaVbbVgZY^HiVW^V 7Vnd[CVeaZh GVkZaad HdggZcid Edh^iVcd HVaZgcd 6bVa[^ 8{eg^ <ja[d[HVaZgcd 6cVX{eg^ 8{eg^ CVeaZh I]Z8Vbe^;aZ\gZ^ Hdji]d[CVeaZh I]Z6bVa[^8dVhi I]Z^haVcYh LN Cdgi]d[CVeaZh FW[ijkc About this book Rough Guides are designed to be good to read and easy to use. The book is divided into the following sections, and you should be able to find whatever you need in one of them. The introductory colour section is designed to give you a feel for Naples and the Amalfi Coast, suggesting when to go and what not to miss, and includes a full list of contents. Then comes basics, for pre-departure information and other practicalities. The guide chapters cover the region in depth, each starting with a highlights panel, introduction and a map to help you plan your route. Contexts fills you in on history, books and film while individual colour sections introduce Neapolitan cuisine and performance. Language gives you an extensive menu reader and enough Italian to get by. 9 781843 537144 ISBN 978-1-84353-714-4 The book concludes with all the small print, including details of how to send in updates and corrections, and a comprehensive index. -

CAPRI È...A Place of Dream. (Pdf 2,4

Posizione geografica Geographical position · Geografische Lage · Posición geográfica · Situation géographique Fra i paralleli 40°30’40” e 40°30’48”N. Fra i meridiani 14°11’54” e 14°16’19” Est di Greenwich Superficie Capri: ettari 400 Anacapri: ettari 636 Altezza massima è m. 589 Capri Giro dell’isola … 9 miglia Clima Clima temperato tipicamente mediterraneo con inverno mite e piovoso ed estate asciutta Between parallels Zwischen den Entre los paralelos Entre les paralleles 40°30’40” and 40°30’48” Breitenkreisen 40°30’40” 40°30’40”N 40°30’40” et 40°30’48” N N and meridians und 40°30’48” N Entre los meridianos Entre les méridiens 14°11’54” and 14°16’19” E Zwischen den 14°11’54” y 14°16’19” 14e11‘54” et 14e16’19“ Area Längenkreisen 14°11’54” Este de Greenwich Est de Greenwich Capri: 988 acres und 14°16’19” östl. von Superficie Surface Anacapri: 1572 acres Greenwich Capri: 400 hectáreas; Capri: 400 ha Maximum height Fläche Anacapri: 636 hectáreas Anacapri: 636 ha 1,920 feet Capri: 400 Hektar Altura máxima Hauter maximum Distances in sea miles Anacapri: 636 Hektar 589 m. m. 589 from: Naples 17; Sorrento Gesamtoberfläche Distancias en millas Distances en milles 7,7; Castellammare 13; 1036 Hektar Höchste marinas marins Amalfi 17,5; Salerno 25; Erhebung über den Nápoles 17; Sorrento 7,7; Naples 17; Sorrento 7,7; lschia 16; Positano 11 Meeresspiegel: 589 Castellammare 13; Castellammare 13; Amalfi Distance round the Entfernung der einzelnen Amalfi 17,5; Salerno 25; 17,5 Salerno 25; lschia A Place of Dream island Orte von Capri, in Ischia 16; Positano 11 16; Positano 11 9 miles Seemeilen ausgedrükt: Vuelta a la isla por mar Tour de l’ île par mer Climate Neapel 17, Sorrento 7,7; 9 millas 9 milles Typical moderate Castellammare 13; Amalfi Clima Climat Mediterranean climate 17,5; Salerno 25; lschia templado típicamente Climat tempéré with mild and rainy 16; Positano 11 mediterráneo con typiquement Regione Campania Assessorato al Turismo e ai Beni Culturali winters and dry summers. -

AD Default.Pdf

our tenter de comprendre l'engouement qu'a toujours suscité Capri, perle de la Méditerranée, il faut s'y rendre à bord de l'un des ferries qui, tous les vendredis après-midi, de mai à septembre, quittent Naples, depuis le môle Beverello, en direction de l'île. Accou- dés au bastingage, les hommes bavardent gaiement sur leur téléphone portable der- nier cri avec leurs amis moins chanceux, retenus au travail à Naples, à Rome ou à Milan. Les femmes - de la grande bour- geoisie ou de l'aristocratie italiennes - affi- chent un look qui rappelle celui de la Jackie Kennedy des années 50: pantalon en coton style pêcheur, sandales à talon plat ou espadrilles à semelle de corde et haut pastel. Seules concessions à l'esprit du temps: le sac à main Gucci ou Prada et les lunettes de soleil Versace ou Fendi. Quelques bijoux de corail ou de turquoises soulignent le caractère décidément estival de cette tenue de villégiature. L'engouement des élites pour Capri n'est pas chose nouvelle. Déjà l'empereur Tibère décidait, en l'an 27 de notre ère, d'aban- donner Rome pour venir s'y installer... Dès le tournant du XVIIe siècle, l'île enchanta 1. Le grand salon de la villa Fersen est orné de marbres précieux, colonnes, stucs, et dorures. 2. Les fêtes organisées parle baron Jacques d'Adelsward -Fersen s'achevaient dans la chambre à opium. les «étrangers». D'abord des Allemands, léopard et se rendait à dîner chez ses amis des Français, des Anglais et des Suédois, avec un serpent enroulé au poignet en puis des Russes et enfin des Américains qui guise de bracelet.. -

Unearth the Essence of the Amalfi Coast with Our Extraordinary Experiences Contents

UNEARTH THE ESSENCE OF THE AMALFI COAST WITH OUR EXTRAORDINARY EXPERIENCES CONTENTS SIGNATURE EXPERIENCES 3 COASTAL LIVING 12 WINING AND DINING 23 TREASURES OF THE LAND 38 ART AND CULTURE 49 – SIGNATURE EXPERIENCES 3 MYSTERIES OF NAPLES Italian writer and journalist Curzio Malaparte once wrote: “Naples is the most mysterious city in Europe. It is the only city in the ancient world that has not perished like Ilium, like Nineveh, like Babylon. It is the only city in the world that has not sunk in the immense shipwreck of ancient civilisation. Naples is a Pompeii that has never been buried.” In the company of an expert storyteller, embark on a journey through the vibrant heart of this mysterious southern capital, discovering decorated catacombs, richly encoded chapels and aged rituals. Customise your tour, choosing from: – Farmacia degli Incurabili: This pharmaceutical laboratory was a meeting point for the Neapolitan Enlightened elite. Discover the intriguing anecdotes of a place where art and science collided. – Biblioteca dei Girolamini: Home to a vast archive of books and opera music since 1586, this is the oldest public library in Naples. – San Gaudioso Catacombs: Concealed beneath the Basilica di Santa Maria della Santità lies one of the most important early Christian cemeteries in Naples. Head underground to unearth the mysterious crypt’s secrets. – Sansevero Chapel: Preserving the Veiled Christ, one of the greatest masterpieces ever carved in marble, this chapel is an iconic example of 18th-century creativity. The statues appear so fluid and soft, you may be tempted to reach out and touch them. Visits may vary according to availability. -

Frank Heller På Capri

© Frank Orton 2016 Frank Heller på Capri Det första mötet Men våren 1920 kom jag till Capri, och med ens var det som om mina ögon öpp- nades och jag blev seende. Jag kastade mig i det kristallklara Medelhavet med sann frenesi och började springa i bergen som en stenget. Capri bestod den gången huvudsakligen av mulåsnestigar. O lårmusklernas vällust under klätt- ringen upp till Salto Tiberio och Monte Solaro! O lungornas vällust, då man där insög den kristallklara luften som var bräddad med vilda dofter! O gommens vällust då man därefter insög det skarpa vita caprivinet med sin lätta arom av svavel! Så entusiastiskt skildrar Frank Heller sitt första möte med Capri.1 Entusiasmen är rent allmänt inte ägnad att förvåna. Nationalencyklopedin, t ex, framhäver öns storslagna skönhet och nämner att den är ett av hela Italiens främsta turistmål. En färsk resebroschyr talar om naturen, som växlar mellan böljande grönska och blommande ängar, dramatiska klippor och hisnande stup.2 Inte för inte har ön be- gåvats med epitetet ”Medelhavets pärla”. Med decenniers erfarenhet av det moderna Capri som mångårig intendent vid den Axel Muntheska Stiftelsen Villa San Michele förmedlar den ungerskfödde arki- tekten Levente Erdeös3 dock en något bredare bild. Han framhåller bl a det mot- sägelsefulla förhållandet mellan Capris två ansikten. På denna poesins och le- gendernas ö finner man nämligen naturens skönhet och harmoni i en fredlig men spänningsladdad samlevnad med den ohejdade materialismens och det så ofta bedrägliga framstegets anda.4 Han tänker förstås inte minst på turismen och vad den kan föra med sig. Belägen vid södra inloppet till Neapelbukten, rakt söder om Neapel och Vesuvi- us, består Capri av två branta, 600 meter höga kalkstensformationer med en sänka emellan. -

Travel's Taste

Travel’s taste YOUR LUXURY TRAVEL PARTNER IN ITALY www.italycreative.it Amalfi Coast Amalfi More about: things to know Coast www.italycreative.it Deemed by Unesco to be an outstanding example of a Mediterranean landscape, the Amalfi Coast is a beguiling combination of great beauty and gripping drama: coastal mountains plunge into the sea in a stunning vertical scene of precipitous crags, picturesque towns and lush forests. Most hotels and villas are open from March/April through October/November. The towns on the water with beaches include Amalfi, Atrani, Cetara, Furore, Maiori, Minori, Praiano, Positano, and Vietri sul Mare. Towns higher up on the cliffs include Agerola, Ravello, Scala, and Tramonti. Amalfi Coast is crossed by Strada Statale 163 Amalfitana (world-famous known as Amalfi Drive), a 50km (30 miles) stretch of road from north to south. If we take the two entrance points to the Amalfi Coast with Sorrento in the north and Salerno in the south, the road goes through the towns in this order: Positano | Praiano | Amalfi | Atrani | Minori | Maiori | Cetara | Vietri Sul Mare It's important to know the order as that would make exploring the towns a bit easier. The Sorrento to Salerno direction is more preferrable as, by being in the right lane, you are right next to the cliffs with no opposing traffic to block your view. There are no trains serving the Amalfi Coast. HOTELS selection Amalfi à POSITANO Coast www.italycreative.it Spread between four villas, each of the suites offers a unique blend of carefree comfort and careful attention to detail. -

Amalfi Coast Capri-Amalfi-Ischia-Procida

Amalfi Coast Capri-Amalfi-Ischia-Procida Cabin Charter Cruises by GoFunSailing Itinerary: Procida - Capri - Amalfi - Positano - Praiano – Ischia One of the iconic symbols of Sorrento and the Amalfi Coast, the lemons produced in this beautiful part of Campania have been prized for centuries for their intense flavor and healthy properties. The production of lemons on the steep and rocky cliff sides along the Sorrento Peninsula is anything but easy. Driving on the Amalfi Coast Road, you’ll spot terraces of lemon groves climbing high up the steep cliffs. It’s quite the experience to spot the bright yellow lemons caught somewhere between the majestic mountains and the blue Mediterranean Sea. Sat: Embark in Procida island 3pm - overnight in marine Embarkment in Procida, introductory briefing with the skipper, accommodation in double cabin. Galley boat storage. Evening at leisure in the beautiful village of Marina grande, enjoying the nearby Coricella village. Mooring, overnight. Sun : Marvellous isand of Capri Breakfast in Procida and sailing cruise to magic Capri and the “faraglioni” (scenic, prestigiuos rocks on the sea). Short swimming brake at famous “Galli“, and direct to Marina Piccola shore. Free time, dinner, overnight. Mon : Capri island Island of Capri round trip is something not to be missed, quite a unique exprience, made up with pleasant surprises... the coast of Capri is varied, rich in rocky spots, sandy bays, and marine caves. The full round trip will take half a day (2/3 hrs), indulging with relax and enjoyment. Lunch in one of the many Anacapri restaurants, time at leisure in the small “Piazzetta”. -

Avviso Pubblico – Fase I Per L

AVVISO PUBBLICO – FASE I PER L’INDIVIDUAZIONE DI 45 DESTINATARI PERCORSI DI EMPOWERMENT AZIONE B) - PERCORSI FORMATIVI “KEY COMPETENCE” “CENTRO TERRITORIALE di INCLUSIONE “KEY OF CHANGE” AZIONI 9.1.2, 9.1.3, 9.2.1, 9.2.2 PROGRAMMA I.T.I.A. INTESE TERRITORIALI DI INCLUSIONE ATTIVA P.O.R. CAMPANIA FSE 2014-2020, ASSE II OBIETTIVI SPECIFICI 6 -7 D.D. n. 191 del 22.06.2018 CUP J19D18000070006 Approvato con Determina R.G. 1542 del 14/07/2020 PREMESSO CHE: - il Coordinamento Istituzionale dell’Ambito S2, costituito ed operante ex art. 11 della Legge Regionale della Campania 23 ottobre 2007, n.11 “Legge per la dignità e la cittadinanza sociale”, come modificata dalla Legge regionale della Campania N. 15 del 06/07/2012, è composto dai Sindaci dei Comuni di: Amalfi, Atrani, Cava de’ Tirreni, Cetara, Conca de’Marini, Furore, Maiori, Minori, Positano, Praiano, Ravello, Scala, Tramonti, Vietri Sul Mare; - in data 21 novembre 2016 è stato sottoscritto tra i Comuni dell’Ambito S2, la Provincia di Salerno e l’ASL Salerno, l’Accordo di Programma finalizzato alla realizzazione in forma associata del Piano Sociale di Zona S2 Cava de’ Tirreni- Costiera Amalfitana; - con decreto dirigenziale n. 191 del 22 giugno 2018, la Regione Campania ha approvato l’Avviso Pubblico non competitivo “I.T.I.A. Intese Territoriali di Inclusione Attiva”, a valere sull’Asse II POR Campania FSE 2014/2020, finalizzato a promuovere la costituzione di Intese Territoriali di Inclusione Attiva per l’attuazione di misure di contrasto alla povertà attraverso la realizzazione di Centri Territoriali di Inclusione; - con decreto dirigenziale della Direzione Generale per le Politiche Sociali e Socio-Sanitarie della Regione Campania n. -

How to Get from Naples to Amalfi Coast

By Wanderlust Storytellers Quick Overview: • Day 1: Drive to Amalfi Coast and explore Positano • Day 2: Enjoy the stunning Ilse of Capri • Day 3: Explore the beautiful coastal towns along the Amalfi Coast drive Accommodation: • 2 Nights at either Positano, Praiano, Ravello or Amalfi (We recommend 3 nights in Amalfi) HELPFUL INFORMATION When to Go: May – June and September – October Try to avoid heading there in the middle of summer as it will be sweltering hot and you will find crowds everywhere! How Long Should I Stay on the Amalfi Coast? We highly recommend a minimum of 3 days and 4 nights. Most travelers choose to spend 7 days on Amalfi Coast which is the optimum amount of days to fit in all the towns, walks, beaches and day trips. Which Town Should I Stay at on the Amalfi Coast? Our absolutely favourite town to stay in is Positano. It is truly the most beautiful out of all the towns but unfortunately it is also one of the costlier ones to stay at. Read more about Positano in our guide here. If you need help in figuring out where to stay, you will find our detailed comparison table and review guide of the towns beneficial. How to get from Naples to Amalfi Coast: • Options: You have the option of catching local transport (bus, train, ferry); grabbing a private transfer (we personally love Blacklane Transfers); or Renting a Car (our personal favourite method). • Time Required to get from Naples to Positano: Around 1.30 hours (more if driving in rush hour traffic) Day One POSITANO ACCOMMODATION: Amalfi MORNING | Drive from Naples to Positano Depending on your arrival time in Naples, you could either visit Pompeii or Sorrento on the way down to Positano. -

Gardens of Campania 4 – 9 May 2018

Italy: Gardens of Campania 4 – 9 May 2018 May 4 Naples ( D ) Arrival in Naples airport and private transfer to your 4 star hotel Santa Lucia Time at leisure and dinner at the gourmet restaurant of the hotel where you will taste the best of the Neapolitan cuisine. May 5 Naples, Santa Chiara cloister, Botanical Garden ( B ) This morning you will meet your guide at the hotel, then you will reach by bus the Cloister of Santa Chiara. The gardens of the cloister of Santa Chiara are of not only horticultural but also great historical and cultural interest. The cloisters are located behind the Gothic Church built in 1320. You have very little information about the origins of the cloister gardens as the Monastery allowed its nuns very little contact with the outside world. In the 1700's, life in the Monastery changed significantly and the Mother Superior engaged the Architect Domenico Antonio Vaccaro to decorate the cloister which was in that time used also for parties and concerts. Vaccaro built the gardens as we see them today including the 72 tile covered pillars of the pergola, the tile covered benches and fountains, tiles being a traditional form of art in Campania. The plantings in the raised flower beds are representative of the antique monastic tradition with vegetables and citrus fruits as well as ornamental plants. Then your guide will lead you on a short walk through the street of “Spaccanapoli” and you will reach Piazza San Domenico where you will taste the Naples’ typical pastry “ Sfogliatella” with a legendary Espresso . -

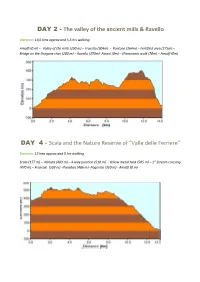

DAY 2 - the Valley of the Ancient Mills & Ravello

DAY 2 - The valley of the ancient mills & Ravello Distance: 13,6 kms approx and 5,5 hrs walking Amalfi (0 m) – Valley of the mills (250 m) – Frassito (304m) - Pontone (264m) – Fortified area (275m) – Bridge on the Dragone river (200 m) – Ravello (370m)- Atrani (0m) – (Panoramic walk (70m) – Amalfi (0m) DAY 4 - Scala and the Nature Reserve of “Valle delle Ferriere” Distance : 13 kms approx and 5 hrs walking Scala (377 m) – Minuta (403 m) – 4-way junction (510 m) - Yellow metal tank (505 m) – 1st Stream crossing (470 m) – Frascale (503 m) –Paradiso (486 m)- Pogerola (310 m) - Amalfi (0 m) DAY 5 - Today you can choose between two options depending on your level of fitness. 1st OPTION: Tre Calli Hike (circular walk Agerola – tre calli – Agerola) + optional walk (2 nd option) from Bomerano to Colle Serra and return to Bomerano – moderate - min 4,5 – max 6 hrs 2nd OPTION : Walk From Bomerano to Colle Serra and return to Bomerano – easy – minimum 1,5 hrs Mt. Tre Calli hike Distance: 10 kms approx and 4,5 hrs walking Bomerano (635 m) – Monte Tre Calli (1122 m) – Monte Calabrice (1143 m) - Capo Muro (1079 m) – Bomerano (635 m) 2nd option - Walk from Bomerano to Colle Serra and return. Distance: 5 kms approx and 1,5hrs walking Bomerano Square – Piazza Capasso (635 m.) - Colle Serra (573 m.) – Piazza Capasso (635 m.)- Bomerano Square DAY 6 - San Lazzaro - Fjord of Furore - Praiano Distance: 11 kms approx and 5 hrs walking San Lazzaro (620 m) – Monastery of Santa Rosa (250 m) – S. -

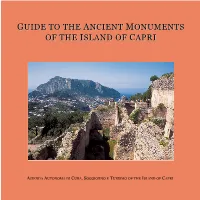

Guide to the Ancient Monuments of the Island of Capri

GGUIDEUIDE TOTO THETHE AANCIENTNCIENT MMONUMENTSONUMENTS OFOF THETHE IISLANDSLAND OFOF CCAPRIAPRI AZIENDA AUTONOMA DI CURA, SOGGIORNO E TURISMO OF THE ISLAND OF CAPRI Index 2 History 6 Grotta delle Felci 7 Muro greco 7 Scala fenicia 8 Palazzo a Mare 10 Villa di Damecuta 12 Villa Jovis Villa Jovis. 15 Villa di Gradola - Grotta Azzurra 16 Grottoes and nymphaea 16 Grotta di Matermania 17 Grotta del Castiglione 17 Grotta dell’Arsenale 18 Detailed studies 19 Museums and libraries For up-to-date information on monument opening hours and itineraries, please contact Information Offices of Azienda Autonoma di Cura, Soggiorno e Turismo of the Island of Capri: Capri, piazza Umberto I - tel. +39 0818370686 Villa di Damecuta. Marina Grande, banchina del Porto - tel. +39 0818370634 Anacapri, via Giuseppe Orlandi - tel +39 0818371524 www.capritourism.com Guide produced by OEBALUS ASSOCIAZIONE CULTURALE ONLUS Via San Costanzo, 8 - Capri www.oebalus.org with the collaboration of SOPRINTENDENZA ARCHEOLOGICA DELLE PROVINCE DI NAPOLI E CASERTA Ufficio scavi Capri, via Certosa - Capri tel. +39 0818370381 Texts by EDUARDO FEDERICO (history) Grotta di Matermania. ROBERTA BELLI (archaeology) CLAUDIO GIARDINO (Grotta delle Felci) Photographs by MARCO AMITRANO UMBERTO D’ANIELLO (page 1) MIMMO JODICE (back cover) Co-ordination ELIO SICA Translations by QUADRIVIO Printed by Scala fenicia. SAMA Via Masullo I traversa, 10 - Quarto (NA) www.samacolors.com GUIDE TO THE ANCIENT MONUMENTS OF THE ISLAND OF CAPRI AZIENDA AUTONOMA DI CURA, SOGGIORNO E TURISMO OF THE ISLAND OF CAPRI History Although rather poorly document- independent island history. ed by ancient authors, the history The history of Capri between the of Capri involves many characters 4th millennium BC and the 8th cen- of notable importance.