Dramatic Aspirations at Villa Borghese: the Theatrics of Bernini's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Name of Object: Apollo and Daphne Location: Rome, Italy Holding

Name of Object: Apollo and Daphne Location: Rome, Latium, Italy Holding Museum: Borghese Gallery Date of Object: 1622–1625 Artist(s) / Craftsperson(s): Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598, Naples-1680, Rome) Museum Inventory Number: CV Material(s) / Technique(s): Marble Dimensions: h: 243 cm Provenance: Borghese Collection Type of object: Sculpture Description: This sculpture is considered one of the masterpieces in the history of art. Bernini began sculpting it in 1622 after he finished The Rape of Proserpina. He stopped working on it from 1623 to 1624 to sculpt David, before completing it in 1625. With notable technical accuracy, the natural agility of this work shows the astonishing moment when the nymph turns into a laurel tree. The artist uses his exceptional technical skill to turn the marble into roots, leaves and windswept hair. Psychological research, combined with typically Baroque expressiveness, renders the emotion of Daphnes terror, caught by the god in her desperate journey, still ignorant of her ongoing transformation. Apollo, thinking he has achieved his objective, is caught in the moment he becomes aware of the metamorphosis, before he is able to react, watching astonished as his victim turns into a laurel tree. For Apollos head, Bernini looked to Apollo Belvedere, which was in the Vatican at the time. The base includes two scrolls, the first containing the lines of the distich by Maffeo Barberini, a friend of Cardinal Scipione Borghese and future Pope Urban VIII. It explores the theme of vanitas in beauty and pleasure, rendered as a Christian moralisation of a profane theme. The second scroll was added in the mid-1700s. -

An Art Lover's

INSIGHT DELICIOUSLY TRAVEL AND SMALLER SEAMLESS, EXPERIENCES AUTHENTIC STAY IN STYLE GROUP STRESS-FREE DINING CAMARADERIE TRAVEL AN ART LOVER’S TASTE OF EUROPE 15 DAYS | Departing 26 September 2021 A cultural journey, visiting some of the best art galleries and museums in Europe while enjoying the sights and tastes of a selection of Europe’s most loved cities. INSIGHTVACATIONS.COM #INSIGHTMOMENTS An Art Lover’s Taste of EuropeThe Louvre, Paris Itinerary DAY 1: ARRIVAL ROME DAY 3: GALLERIA BORGHESE DAY 5: RENAISSANCE FLORENCE Welcome to Rome! On arrival AND FREE TIME With a Local Expert, visit the Uffizi Gallery, complimentary transfers are provided to A highlight for art lovers today, a visit one of the oldest and most famous art your hotel, departing the airport at 09.30, to the Galleria Borghese, which houses museums in Europe. Admire works by 12.30 and 15.30hrs. Later, meet your a substantial part of the Borghese Michelangelo, Botticelli and Raphael Travel Director for a Welcome Dinner in a collection of paintings, sculptures and amongst other masterpieces. Then local restaurant. (DW) antiquities, begun by Cardinal Scipione embark on a sightseeing trip to see the Hotel: Kolbe, Rome – 3 nights Borghese, the nephew of Pope Paul V who multi coloured marble cathedral, bell reigned from 1605 to 1621. The rest of the tower and baptistry, adorned by Ghiberti’s “Gate of Paradise”. This evening is yours DAY 2: ROME SIGHTSEEING day is yours to explore before joining for dinner at a local restaurant this evening. to enjoy the ambience of this timeless The day is devoted to the Eternal City. -

Ist. Arts & Culture Festival First Global Edition Kicks

IST. ARTS & CULTURE FESTIVAL FIRST GLOBAL EDITION KICKS OFF IN ROME, ITALY ON MAY 31 ISTANBUL ’74 C o - Founders Demet Muftuoglu Eseli & Alphan Esel i to Co - curate IST.FEST.ROME With Delfina Delettrez Fendi and Nico Vascellari Demet Muftuoglu Eseli & Alphan Eseli , Co - Founders of ISTANBUL’74 launch the first global edition of IST. Arts & Culture Festival i n the city of Rome , the artistic an d cultural center of the world that has played host to some of the most impressive art and architecture achieved by human civilization , on May 31 st - June 2 nd 2019. Co - c urated by Demet Muftuoglu Eseli, Alphan Eseli, with Delfina Delettrez Fendi and Nico Vascellari , the IST.FEST. ROME will bring together some of the world’s most talented and creative minds , and leading cultural figures around an inspiring program of panels, talks, exhibitions, performances, screenings and workshops while maintaining its admission - free format. IST. FEST. ROME will focus on the theme: “Self - Expression in the Post - Truth World.” This edition of IST. F estival sets out to explore the ways in which constant changes in our surrounding habitats affect crea tive minds and artistic output. The core mission of the theme is to invoke lively debate around the struggle between reality and make - believe while acknow ledging digital technology and its undeniable power and vast reach as the ultimate tool for self - expression. IST.FEST.ROME will be presented in collaboration with MAXXI, the National Museum of 21st Century Arts , the first Italian national institution dev oted to contemporary creativity designed by the acclaimed architect Zaha Hadid , and Galleria Borghese , one the most respected museums over the world with masterpieces by Bernini and Caravaggio in its collection. -

Impressionist & Modern

Impressionist & Modern Art New York | November 17, 2020 Impressionist & Modern Art New York | Tuesday November 17, 2020 at 5pm EST BONHAMS INQUIRIES BIDS COVID-19 SAFETY STANDARDS 580 Madison Avenue New York Register to bid online by visiting Bonhams’ galleries are currently New York, New York 10022 Molly Ott Ambler www.bonhams.com/26154 subject to government restrictions bonhams.com +1 (917) 206 1636 and arrangements may be subject Bonded pursuant to California [email protected] Alternatively, contact our Client to change. Civil Code Sec. 1812.600; Services department at: Bond No. 57BSBGL0808 Preeya Franklin [email protected] Preview: Lots will be made +1 (917) 206 1617 +1 (212) 644 9001 available for in-person viewing by appointment only. Please [email protected] SALE NUMBER: contact the specialist department IMPORTANT NOTICES 26154 Emily Wilson on impressionist.us@bonhams. Please note that all customers, Lots 1 - 48 +1 (917) 683 9699 com +1 917-206-1696 to arrange irrespective of any previous activity an appointment before visiting [email protected] with Bonhams, are required to have AUCTIONEER our galleries. proof of identity when submitting Ralph Taylor - 2063659-DCA Olivia Grabowsky In accordance with Covid-19 bids. Failure to do this may result in +1 (917) 717 2752 guidelines, it is mandatory that Bonhams & Butterfields your bid not being processed. you wear a face mask and Auctioneers Corp. [email protected] For absentee and telephone bids observe social distancing at all 2077070-DCA times. Additional lot information Los Angeles we require a completed Bidder Registration Form in advance of the and photographs are available Kathy Wong CATALOG: $35 sale. -

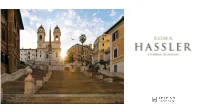

Hassler's Roma: a Publication That Descrive Tutte Le Meraviglie Intorno Al Nostro Al- Describes All the Marvels, Both Hidden and Not, Bergo, Nascoste E Non

HASSLER’S ROMA A CURA DI FILIPPO COSMELLI Prodotto in esclusiva per l’Hotel Hassler direzione creativa: Filippo Cosmelli direzione editoriale: Daniela Bianco fotografie: Alessandro Celani testi: Filippo Cosmelli & Giacomo Levi ricerche iconografiche: Pietro Aldobrandini traduzione: Logos Srls. - Creative services assistente: Carmen Mariel Di Buono mappe disegnate a mano: Mario Camerini progetto grafico: Leonardo Magrelli stampato presso: Varigrafica, Roma Tutti I Diritti Riservati Nessuna parte di questo libro può essere riprodotta in nessuna forma senza il preventivo permesso da parte dell’Hotel Hassler 2018. If/Books · Marchio di Proprietà di If S.r.l. Via di Parione 17, 00186 Roma · www.ifbooks.it Gentilissimi ospiti, cari amici, Dear guests, dear friends, Le strade, le piazze e i monumenti che circonda- The streets, squares and buildings that surround no l’Hotel Hassler sono senza dubbio parte inte- the Hassler Hotel are without a doubt an in- grante della nostra identità. Attraversando ogni tegral part of our identity. Crossing Trinità de mattina la piazza di Trinità de Monti, circonda- Monti every morning, surrounded by the stair- ta dalla scalinata, dal verde brillante del Pincio case, the brilliant greenery of the Pincio and the e dalla quiete di via Gregoriana, è inevitabile silence of Via Gregoriana, the desire to preser- che sorga il desiderio di preservare, e traman- ve and hand so much beauty down to future ge- dare tanta bellezza. È per questo che sono feli- nerations is inevitable. This is why I am pleased ce di presentarvi Hassler’s Roma: un volume che to present Hassler's Roma: a publication that descrive tutte le meraviglie intorno al nostro al- describes all the marvels, both hidden and not, bergo, nascoste e non. -

Pursuing the Perspective. Conflicts and Accidents in the Gran Palazzo Degli Eccellentissimi Borghesi a Ripetta

Publisher: FeDOA Press - Centro di Ateneo per le Biblioteche dell’Università di Napoli Federico II Registered in Italy Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.serena.unina.it/index.php/eikonocity/index Pursuing the Perspective. Conflicts and Accidents in the Gran Palazzo degli Eccellentissimi Borghesi a Ripetta Fabio Colonnese Sapienza Università di Roma - Dipartimento di Storia, Disegno e Restauro dell’Architettura To cite this article: Colonnese, F. (2021).Pursuing the Perspective. Conflicts and Accidents in theGran Palazzo degli Eccellentissimi Borghesi a Ripetta: Eikonocity, 2021, anno VI, n. 1, 9-25, DOI: 110.6092/2499-1422/6156 To link to this article:http://dx.doi.org/10.6092/2499-1422/6156 FeDOA Press makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. FeDOA Press, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Versions of published FeDOA Press and Routledge Open articles and FeDOA Press and Routledge Open Select articles posted to institutional or subject repositories or any other third-party website are without warranty from FeDOA Press of any kind, either expressed or im- plied, including, but not limited to, warranties of merchantability, fitness for a particular purpose, or non-infringement. Any opinions and views expressed in this article are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by FeDOA Press. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. -

C HAPTER THREE Dissertation I on the Waters and Aqueducts Of

Aqueduct Hunting in the Seventeenth Century: Raffaele Fabretti's De aquis et aquaeductibus veteris Romae Harry B. Evans http://www.press.umich.edu/titleDetailDesc.do?id=17141, The University of Michigan Press C HAPTER THREE Dissertation I on the Waters and Aqueducts of Ancient Rome o the distinguished Giovanni Lucio of Trau, Raffaello Fabretti, son of T Gaspare, of Urbino, sends greetings. 1. introduction Thanks to your interest in my behalf, the things I wrote to you earlier about the aqueducts I observed around the Anio River do not at all dis- please me. You have in›uenced my diligence by your expressions of praise, both in your own name and in the names of your most learned friends (whom you also have in very large number). As a result, I feel that I am much more eager to pursue the investigation set forth on this subject; I would already have completed it had the abundance of waters from heaven not shown itself opposed to my own watery task. But you should not think that I have been completely idle: indeed, although I was not able to approach for a second time the sources of the Marcia and Claudia, at some distance from me, and not able therefore to follow up my ideas by surer rea- soning, not uselessly, perhaps, will I show you that I have been engaged in the more immediate neighborhood of that aqueduct introduced by Pope Sixtus and called the Acqua Felice from his own name before his ponti‹- 19 Aqueduct Hunting in the Seventeenth Century: Raffaele Fabretti's De aquis et aquaeductibus veteris Romae Harry B. -

Return International Airfares 3-4 Star Accommodation Professional

D aily Breakfast & dinner R eturn International Ai rfares 3 - 4 star accommodation P rDoafeilsys ional loca&l guide AiRrpeoturrtn T Irnatnesrfneartsi onal TrAiainrf atircekse ts 3-4 star accommodation Professional local guide Airport Transfers Train tickets Day 1: Melbourne - - Rome Departure from Melbourne, begin your journey of Italy. Day 2: Rome Arrive in Rom e , a C ity of 3 00 0 yea rs histor y. Italy ’ s capital is a sprawling , cosmopolitan city with nearly 3,000 years of globally influential art , architecture and culture on display . Ancient ruins such as the Roman Forum and the Colosseum evoke the power of the former Roman Empire .Up on arrival , your tour gu ide will meet you at the airport with the warmest greeting. Transfer to hotel . Day 3: Rome Empire Explore Rome after breakfast . You ’ll understand soon why it is defined an “open air mu seum”: as you walk aroun d the ci ty center, yo u’ll s ee the remains of it s glorio us past all around y ou, as you’re making a time travel back to the ancient Rome empire era. Visit C olosseum *, Arch of Constantine, Roman Forum*. Walk over to Venice Square and way up the Campidoglio Hill you will visit Capitoline Museums*. opened to the public since 1734.The Capitoline Museums are considered the first museum in the world including a large number of ancient Roman statues , inscriptions , and other artifacts ; a collection of medieval and Renaissance art ; and collections of jewels , coins and other items . Transfer ba c k to ho t el after din ner . -

Rome: a New Planning Strategy

a selected chapter from Rome: A New Planning Strategy by Franco Archibugi draft of a forthcoming book to be published by Gordon and Breach, New York an overview of this book CHAPTER 5: THE NEW STRATEGY FOR ROME 1. The "Catchment Areas" of the New "Urban Centres" 2. The Spatial Distribution of the Catchment Areas Table 2 - Catchment Areas of the Roman Metropolitan System (by thousands of inhabitants) 3. What decentralization of services for the new "urban centres"? 4. What "City Architecture"? 5. What Strategy for "Urban Greenery"? 6. Programmed Mobility 7. A "Metropolitan" Residentiality Notes References Further Reading THE NEW STRATEGY FOR ROME Authentic "polycentrism", therefore, is founded first of all on an evaluation of the "catchment areas" of the services that define it. The location of the centers and infrastructures of such services is a subsequent question (we would say "secondary" if with this adjective is meant not inferiority in importance, but rather a temporal and conceptual subordination). The polycentrism supported here in Rome means, first of all, a theoretical assignation of the potentiality of the catchment area of the Roman system to respective "units" of service that locationally assume the 1 role of realizing the objectives, reasserted by everybody numerous times of: integrating functions, improving accessibility, distances, traveling times, not exceeding the thresholds that have been indicated as "overloading". The locational problem of the new strategy therefore, is posed as a problem of not letting all the users participate in any function in any part of the system (the 2,8 million Roman citizens plus the by now recognized other 700 thousand citizens of the Roman "system"); but to functionally distribute the services in such a way as to not render "indifferent" (but on the contrary very.. -

WORLD YOUTH SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Larry Rachleff, Conductor

109th Program of the 91st Season Interlochen, Michigan * WORLD YOUTH SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Larry Rachleff, conductor Sunday, July 15, 2018 8:00pm, Kresge Auditorium WORLD YOUTH SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Larry Rachleff, conductor PROGRAM Symphony No. 8 in B Minor, D. 759 “Unfinished” ........................................... Franz Schubert Allegro moderato (1797-1828) Andante con moto The Pines of Rome ...................................................................................... Ottorino Respighi The Pines of the Villa Borghese (1879-1936) The Pines Near a Catacomb The Pines of the Janiculum The Pines of the Appian Way The audience is requested to remain seated during the playing of the Interlochen Theme and to refrain from applause upon its completion. * * * PROGRAM NOTES By Amanda Sewell Symphony No. 8 in B Minor, D. 759 “Unfinished” Franz Schubert Franz Schubert was only 31 years old when he died in 1828, and he left this particular symphony unfinished at the time of his death. Although it makes a dramatic story that would parallel the composition of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Requiem, it is not true that Schubert was working on this symphony up to the moment of his death. Schubert began composing this symphony in 1822, writing only two complete movements before setting it aside. He may have returned to it later if he had lived longer, but it seems clear that he stopped working on this piece because he wasn’t interested in finishing it at the time. The two completed movements were both very typical in form and style of symphonies at the time. The first is an Allegro moderato in sonata form, and the second is an Andante con moto that alternates two contrasting themes. -

Hassler Roma Overview Presentation.Pdf

The residence of choice for luxury accommodation The Hassler Roma, one of the most prestigious hotels in the world, is located in the heart of Rome next to the Trinità dei Monti church at the top of the famous Spanish Steps and Piazza di Spagna. It is owned by President & Managing Director Roberto E. Wirth. Elegance, style, and the highest quality of service have made the Hassler the very symbol of international hospitality, making it the preferred destination of VIPs all over the world. Classic Italian style and flair Eighty-seven rooms and suites, each uniquely decorated and fitted with all the modern comforts, offer an unparalleled city or lovely courtyard or garden view. All the rooms are beautifully appointed, featuring warm light and bright colors. Classic Rooms Elegantly furnished, the Classic double is perfect for a comfortable single occupancy sojourn or a couple’s weekend getaway at one of the best Rome City centre hotels. All Classic doubles feature king or twin beds, refined marble bathrooms and work desks. Classic double rooms have either garden-side or city view. Approx. 23 sq. mt. Deluxe Rooms Each Deluxe double room offers an harmonious atmosphere, with a unique blend of modern convenience and classical charm. Equipped with all the necessary advanced technologies, either with king or twin beds, marble bathroom, the Deluxe rooms are designed with ultimate guest comfort. Many of the Deluxe rooms are interconnecting either with a Classic Suite or a Double Deluxe. Deluxe double rooms are ideal for one who wishes to experience a romantic holiday escape in Rome or is visiting for a business matter. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) The Artful Hermit. Cardinal Odoardo Farnese's religious patronage and the spiritual maening of landsacpe around 1600 Witte, A.A. Publication date 2004 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Witte, A. A. (2004). The Artful Hermit. Cardinal Odoardo Farnese's religious patronage and the spiritual maening of landsacpe around 1600. in eigen beheer. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:07 Oct 2021 3.. PATRONAGE, PROTECTORATE AND REGULAR REFORMS Orazionee e Morte Thee name of the brotherhood of Santa Maria dell'Orazione e Morte. from which Farnese rented thee Camerino degli i:remiti in !61 ! alluded to its two aims: orazione indicated the act of prayer, andd morte referred to burying the dead.