Representation of Deities of the Maya Manuscripts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Maya Afterlife Iconography: Traveling Between Worlds

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2006 Ancient Maya Afterlife Iconography: Traveling Between Worlds Mosley Dianna Wilson University of Central Florida Part of the Anthropology Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Wilson, Mosley Dianna, "Ancient Maya Afterlife Iconography: Traveling Between Worlds" (2006). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 853. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/853 ANCIENT MAYA AFTERLIFE ICONOGRAPHY: TRAVELING BETWEEN WORLDS by DIANNA WILSON MOSLEY B.A. University of Central Florida, 2000 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Liberal Studies in the College of Graduate Studies at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2006 i ABSTRACT The ancient Maya afterlife is a rich and voluminous topic. Unfortunately, much of the material currently utilized for interpretations about the ancient Maya comes from publications written after contact by the Spanish or from artifacts with no context, likely looted items. Both sources of information can be problematic and can skew interpretations. Cosmological tales documented after the Spanish invasion show evidence of the religious conversion that was underway. Noncontextual artifacts are often altered in order to make them more marketable. An example of an iconographic theme that is incorporated into the surviving media of the ancient Maya, but that is not mentioned in ethnographically-recorded myths or represented in the iconography from most noncontextual objects, are the “travelers”: a group of gods, humans, and animals who occupy a unique niche in the ancient Maya cosmology. -

The Political Economy of Linguistic and Social Exchange Among The

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 Mayas, Markets, and Multilingualism: The Political Economy of Linguistic and Social Exchange in Cobá, Quintana Roo, Mexico Stephanie Joann Litka Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES MAYAS, MARKETS, AND MULTILINGUALISM: THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF LINGUISTIC AND SOCIAL EXCHANGE IN COBÁ, QUINTANA ROO, MEXICO By STEPHANIE JOANN LITKA A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Anthropology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Copyright 2012 Stephanie JoAnn Litka All Rights Reserved Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2012 Stephanie JoAnn Litka defended this dissertation on October 28, 2011 . The members of the supervisory committee were: Michael Uzendoski Professor Directing Dissertation Robinson Herrera University Representative Joseph Hellweg Committee Member Mary Pohl Committee Member Gretchen Sunderman Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the [thesis/treatise/dissertation] has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For the people of Cobá, Mexico Who opened their homes, jobs, and hearts to me iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My fieldwork in Cobá was generously funded by the National Science Foundation, the Florida State University Center for Creative Research, and the Tinker Field Grant. I extend heartfelt gratitude to each organization for their support. In Mexico, I thank first and foremost the people of Cobá who welcomed me into their community over twelve years ago. I consider this town my second home and cherish the life-long friendships that have developed during this time. -

Glad Intellectual Dependence on God: a Theistic Account of Intellectual Humility"

Center for Faith & Learning Scholar Program Reading for Dinner Dialogue #3 Winter 2020 "Glad Intellectual Dependence on God: A Theistic Account of Intellectual Humility" by Peter C. Hill, Kent Dunnington and M. Elizabeth Lewis Hall From: The Journal of Psychology and Christianity, 2018, Vol. 37, No.3, 195-204 Journal of Psychology and Christianity Copyright 2018 Christian Association for Psychological Studies 2018, Vol. 37, No.3, 195-204 ISSN 0733-4273 Glad Intellectual Dependence on God: A Theistic Account of Intellectual Humility Peter C. Hill Kent Dunnington M. Elizabeth Lewis Hall Biola University We present a view of intellectual humility as it may be experienced and expressed by a theist. From a religious cultural perspective and drawing primarily on Augustine, we argue that intellectual humility for the theist is based on glad intellectual dependence on God. It is evidenced in five markers of IH: (a) proper unconcern about one’s intellectual status and entitlements; (b) proper concern about one’s intellectual failures and limitations; (c) proper posture of intellectual submis- sion to divine teaching; (d) order epistemic attitudes that properly reflect one’s justification for one’s views, including those views held on the basis of religious testimony, church authority, interpreta- tions of scripture, and the like; and (e) proper view of the divine orientation of inquiry. Implica- tions of this perspective for the study of intellectual humility are provided. Positive psychology’s critique that the study especially relevant in an age where people of what is “right” about people has been frequently ignore, belittle, or even aggressive- understudied has opened the door to investi- ly attack alternative ideas, beliefs, or perspec- gate the psychological study of virtue. -

Panthéon Maya

Liste des divinités et des démons de la mythologie des mayas. Les noms sont tirés du Popol Vuh des Mayas Quichés, des livres de Chilam Balam et de Diego de Landa ainsi que des divers codex. Divinité Dieu Déesse Démon Monstre Animal Humain AB KIN XOC Dieu de poésie. ACAN Dieu des boissons fermentées et de l'ivresse. ACANTUN Quatre démons associés à une couleur et à un point cardinal. Ils sont présents lors du nouvel an maya et lors des cérémonies de sculpture des statues. ACAT Dieu des tatouages. AH CHICUM EK Autre nom de Xamen Ek. AH CHUY KAKA Dieu de la guerre connu sous le nom du "destructeur de feu". AH CUN CAN Dieu de la guerre connu comme le "charmeur de serpents". AH KINCHIL Dieu solaire (voir Kinich Ahau). AHAU CHAMAHEZ Un des deux dieux de la médecine. AHMAKIQ Dieu de l'agriculture qui enferma le vent quand il menaçait de détruire les récoltes. AH MUNCEN CAB Dieu du miel et des abeilles sans dard; il est patron des apiculteurs. AH MUN Dieu du maïs et de la végétation. AH PEKU Dieu du Tonnerre. AH PUCH ou AH CIMI ou AH CIZIN Dieu de la Mort qui régnait sur le Metnal, le neuvième niveau de l'inframonde. AH RAXA LAC DMieu de lYa Terre.THOLOGICA.FR AH RAXA TZEL Dieu du ciel AH TABAI Dieu de la Chasse. AH UUC TICAB Dieu de la Terre. 1 AHAU CHAMAHEZ Dieu de la Médecine et de la Guérison. AHAU KIN voir Kinich Ahau. AHOACATI Dieu de la Fertilité AHTOLTECAT Dieu des orfèvres. -

Sermon Discussion

SERMON DISCUSSION This LifeGroup will focus it’s discussion on the Spring Semester sermon series God Is... During this series we will have a deeper understanding on the Character of God. There is nothing more important than a right understanding of God. Every day we have fears, concerns, and demands that distract our lives and compete for our attention. Before long, we begin to filter God’s character and nature through our experiences, creating a god in our image. God Is... is about undoing this —stripping away the false picture that we have painted and restoring a proper view of who God is based on what he has revealed to us in Scripture. WEEK 1 - The Mystery of God WEEK 2 - The Holiness of God WEEK 3 - The Faithfulness of God WEEK 4 - The Wrath of God WEEK 5 – The Sovereignty of God WEEK 6 - The Mercy of God WEEK 7 - The Jealous God WEEK 8 - The Beauty of God WEEK 9 - The Love of God WEEK 1 - GOD IS...MYSTERY: THE MYSTERY OF GOD WEEK 1 - GOD IS...MYSTERY: THE MYSTERY OF GOD God is never boring. Frustrating, confusing, enlightening, shocking, and even funny, but He is never boring. If we think that God is boring, then we are obviously worshipping a God of our own making and not the Creator, Redeemer, and Sustainer of the universe and of our own lives. God is incomprehensible, but the mystery of God is revealed in Christ. There are some things we will always wonder about and question because God’s thoughts are higher that our thoughts, and His ways are higher than our ways. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Many books were read and researched in the compilation of Binford, L. R, 1983, Working at Archaeology. Academic Press, The Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology: New York. Binford, L. R, and Binford, S. R (eds.), 1968, New Perspectives in American Museum of Natural History, 1993, The First Humans. Archaeology. Aldine, Chicago. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Braidwood, R 1.,1960, Archaeologists and What They Do. Franklin American Museum of Natural History, 1993, People of the Stone Watts, New York. Age. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Branigan, Keith (ed.), 1982, The Atlas ofArchaeology. St. Martin's, American Museum of Natural History, 1994, New World and Pacific New York. Civilizations. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Bray, w., and Tump, D., 1972, Penguin Dictionary ofArchaeology. American Museum of Natural History, 1994, Old World Civiliza Penguin, New York. tions. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Brennan, L., 1973, Beginner's Guide to Archaeology. Stackpole Ashmore, w., and Sharer, R. J., 1988, Discovering Our Past: A Brief Books, Harrisburg, PA. Introduction to Archaeology. Mayfield, Mountain View, CA. Broderick, M., and Morton, A. A., 1924, A Concise Dictionary of Atkinson, R J. C., 1985, Field Archaeology, 2d ed. Hyperion, New Egyptian Archaeology. Ares Publishers, Chicago. York. Brothwell, D., 1963, Digging Up Bones: The Excavation, Treatment Bacon, E. (ed.), 1976, The Great Archaeologists. Bobbs-Merrill, and Study ofHuman Skeletal Remains. British Museum, London. New York. Brothwell, D., and Higgs, E. (eds.), 1969, Science in Archaeology, Bahn, P., 1993, Collins Dictionary of Archaeology. ABC-CLIO, 2d ed. Thames and Hudson, London. Santa Barbara, CA. Budge, E. A. Wallis, 1929, The Rosetta Stone. Dover, New York. Bahn, P. -

In John's Gospel

John Carroll University Carroll Collected Masters Essays Theses, Essays, and Senior Honors Projects Winter 2016 A STUDY OF “BELIEVING” AND “LOVE” IN JOHN’S GOSPEL Patrick Sullivan John Carroll University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://collected.jcu.edu/mastersessays Part of the Biblical Studies Commons Recommended Citation Sullivan, Patrick, "A STUDY OF “BELIEVING” AND “LOVE” IN JOHN’S GOSPEL" (2016). Masters Essays. 56. http://collected.jcu.edu/mastersessays/56 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Essays, and Senior Honors Projects at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Essays by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A STUDY OF “BELIEVING” AND “LOVE” IN JOHN’S GOSPEL An Essay Submitted to The Office of Graduate Studies College of Arts and Sciences John Carroll University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts By Patrick Sullivan 2016 The essay of Patrick Sullivan is hereby accepted: ________________________________________ ____________________ Advisor — Dr. Sheila E. McGinn Date I certify that this is the original document ________________________________________ ___________________________ Author — Patrick Sullivan Date If one reads the Gospel of John through a contemplative lens one can discern a very useful dynamic interplay between the evangelist’s treatment of the words “believe” and “love.” This paper will investigate this dynamic. It will begin by identifying the relevant perspectives that a contemplative brings into an encounter with scripture. After this, there will be a short section exploring John’s use of the word love, and how this understanding of love is uniquely useful to the contemplative. -

Grave Exclamations: an Analysis of Tombstones and Their Seu As Narrative of Self Lacey Jae Ritter Minnesota State University - Mankato

Minnesota State University, Mankato Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects 2012 Grave Exclamations: An Analysis of Tombstones and Their seU as Narrative of Self Lacey Jae Ritter Minnesota State University - Mankato Follow this and additional works at: http://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/etds Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Ritter, Lacey Jae, "Grave Exclamations: An Analysis of Tombstones and Their sU e as Narrative of Self" (2012). Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects. Paper 242. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations, and Other Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. Grave Exclamations: An Analysis of Tombstones and Their Use as Narrative of Self By Lacey J. Ritter A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Sociology: Teaching Emphasis at Minnesota State University, Mankato May, 2012 April 3, 2012 This thesis paper has been examined and approved. Examining Committee: Dr. Leah Rogne, Chairperson Dr. Emily Boyd Dr. Kathryn Elliot i Ritter, Lacey. 2012. Grave Exclamations: An Analysis of Tombstones and their Use as Narrative of Self. Master’s Thesis. Minnesota State University, Mankato. PP.69. We establish our selves through narratives—with others and by ourselves— during life. What happens, however, when a person dies? The following paper looks at the way narratives about the deceased’s selves are created by the bereaved after their loved ones have died. -

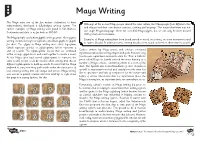

Maya Writing Comprehension Questions

Maya Writing The Maya were one of the five ancient civilisations to have Although all the ancient Maya people shared the same culture, the Maya people from different cities independently developed a fully-fledged writing system. The and villages had their own distinct customs, clothing and language. This meant that there was not earliest examples of Maya writing were found in San Bartolo, one single Mayan language. There are over 800 Maya glyphs, but we can only decipher around Guatemala and date to as far back as 300 BC. 400 of them at the moment. The Maya people used a hieroglyphic writing system. Hieroglyphic Examples of Maya writing have been found carved in wood, on pottery, on stone monuments and writing consisted of signs or symbols called hieroglyphs or glyphs in codices (books). In addition to this, writing has also been found on lintels in their temples as well. for short. The glyphs in Maya writing were either logograms (which represent words), or syllabograms (which represent a unit of sound). The syllabograms would then be combined Codices written by Maya priests and scholars contained within a single glyph block and read together to create a word. information about astronomy, religion and gods. However, only As the Maya often had several syllabograms to represent the four known copies have survived to date. In 1562, a Catholic same sound, people could be creative when writing and choose priest called Diego de Landa ordered the mass burning of a different syllabograms to build up words. It seems that the Maya number of Maya codices, condemning them as a work of the preferred to vary how they spelt words within the same piece of devil. -

On the Origin of the Different Mayan Calendars Thomas Chanier

On the origin of the different Mayan Calendars Thomas Chanier To cite this version: Thomas Chanier. On the origin of the different Mayan Calendars. 2014. hal-01018037v1 HAL Id: hal-01018037 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01018037v1 Submitted on 3 Jul 2014 (v1), last revised 14 Jan 2015 (v3) HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. On the origin of the different Mayan Calendars T. Chanier∗1 1 Department of Physics, University of Namur, rue de Bruxelles 61, B-5000 Namur, Belgium The Maya were known for their astronomical proficiency. Whereas Mayan mathematics were based on a vigesimal system, they used a different base when dealing with long periods of time, the Long Count Calendar (LCC), composed of different Long Count Periods: the Tun of 360 days, the Katun of 7200 days and the Baktun of 144000 days. There were three other calendars used in addition to the LCC: a civil year Haab’ of 365 days, a religious year Tzolk’in of 260 days and a 3276- day cycle (combination of the 819-day Kawil cycle and 4 colors-directions). Based on astronomical arguments, we propose here an explanation of the origin of the LCC, the Tzolk’in and the 3276-day cycle. -

Política Internacional Año 4 - Número 7 - Enero/Mayo 2019 - Guatemala

Política Internacional Año 4 - Número 7 - Enero/Mayo 2019 - Guatemala CONTENIDO Presentación 5 ARTICULOS • Fronteras Abiertas, Derechos Humanos y Justicia Global. 9 Juan Carlos Velasco • Migraciones y Apertura Cosmopolita de la Ciudadanía. 29 Javier Peña Echeverría • Migración Internacional y Derechos Fundamentales. 46 Elisabetta Di Castro • ¿Derecho de Fuga? Derecho de Migración y Nacionalidad Cosmopolita. 57 Victor Granado Almena • Perspectivas Internacionales Sobre Migración: Conceptualizar la Simultaneidad. 73 Peggy Levitt & Nina Glick Schiller • Los Movimientos Sociales Transnacionales como Actores del Sistema Internacional. 102 Samuel Noriega Labbé • El Desueto y la Importancia Legal de los Tratados Anglo-Españoles de 1783 y 1786 dentro del Reclamo Guatemalteco en el Diferendo Territorial, Insular y Marítimo. 132 Carlos Arturo Villagrán • La Civilización Maya: Aportes Científicos a la Humanidad. 146 Sara Angelina Solís Castañeda CONTENIDO COLABORACIONES • El Tratado de Libre Comercio Nueva Ventana por la Prosperidad Económica de la Región Centroamericana y Corea. 178 Seok-Hwa Hong • Nuevo Sistema de Gobierno Electrónico busca Mejorar el Servicio Público y la Confianza de los Ciudadanos en Corea del Sur. 180 Seok-Hwa Hong • Emigración, Medioambiente y Lucha contra la Violencia: Tres Importantes Ejes de la Política Exterior del Reino de Marruecos 182 Política Internacional - Año 4 - Número 7 - Enero/Mayo 2019 - Guatemala Presentación Este séptimo número de Política Internacional está dedicado fundamentalmente a la problemática migratoria y a la movilidad de las personas en un mundo cuya característica principal es – además de la globalización económica – la globalización humana como expresión de esa misma movilidad de los seres humanos sobre la tierra, el planeta que alberga a nuestra especie, movilidad que – por supuesto – no es algo novedoso si tomamos como punto de partida la aparición de homo sapiens en el continente africano hace unos 200,000 años. -

The Summons of Death on the Medieval and Renaissance English Stage

The Summons of Death on the Medieval and Renaissance English Stage The Summons of Death on the Medieval and Renaissance English Stage Phoebe S. Spinrad Ohio State University Press Columbus Copyright© 1987 by the Ohio State University Press. All rights reserved. A shorter version of chapter 4 appeared, along with part of chapter 2, as "The Last Temptation of Everyman, in Philological Quarterly 64 (1985): 185-94. Chapter 8 originally appeared as "Measure for Measure and the Art of Not Dying," in Texas Studies in Literature and Language 26 (1984): 74-93. Parts of Chapter 9 are adapted from m y "Coping with Uncertainty in The Duchess of Malfi," in Explorations in Renaissance Culture 6 (1980): 47-63. A shorter version of chapter 10 appeared as "Memento Mockery: Some Skulls on the Renaissance Stage," in Explorations in Renaissance Culture 10 (1984): 1-11. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Spinrad, Phoebe S. The summons of death on the medieval and Renaissance English stage. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. English drama—Early modern and Elizabethan, 1500-1700—History and criticism. 2. English drama— To 1500—History and criticism. 3. Death in literature. 4. Death- History. I. Title. PR658.D4S64 1987 822'.009'354 87-5487 ISBN 0-8142-0443-0 To Karl Snyder and Marjorie Lewis without who m none of this would have been Contents Preface ix I Death Takes a Grisly Shape Medieval and Renaissance Iconography 1 II Answering the Summon s The Art of Dying 27 III Death Takes to the Stage The Mystery Cycles and Early Moralities 50 IV Death