The South China Sea: Crouching Threat and Hidden Dangers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cruising Guide to the Philippines

Cruising Guide to the Philippines For Yachtsmen By Conant M. Webb Draft of 06/16/09 Webb - Cruising Guide to the Phillippines Page 2 INTRODUCTION The Philippines is the second largest archipelago in the world after Indonesia, with around 7,000 islands. Relatively few yachts cruise here, but there seem to be more every year. In most areas it is still rare to run across another yacht. There are pristine coral reefs, turquoise bays and snug anchorages, as well as more metropolitan delights. The Filipino people are very friendly and sometimes embarrassingly hospitable. Their culture is a unique mixture of indigenous, Spanish, Asian and American. Philippine charts are inexpensive and reasonably good. English is widely (although not universally) spoken. The cost of living is very reasonable. This book is intended to meet the particular needs of the cruising yachtsman with a boat in the 10-20 meter range. It supplements (but is not intended to replace) conventional navigational materials, a discussion of which can be found below on page 16. I have tried to make this book accurate, but responsibility for the safety of your vessel and its crew must remain yours alone. CONVENTIONS IN THIS BOOK Coordinates are given for various features to help you find them on a chart, not for uncritical use with GPS. In most cases the position is approximate, and is only given to the nearest whole minute. Where coordinates are expressed more exactly, in decimal minutes or minutes and seconds, the relevant chart is mentioned or WGS 84 is the datum used. See the References section (page 157) for specific details of the chart edition used. -

M.V. Solita's Passage Notes

M.V. SOLITA’S PASSAGE NOTES SABAH BORNEO, MALAYSIA Updated August 2014 1 CONTENTS General comments Visas 4 Access to overseas funds 4 Phone and Internet 4 Weather 5 Navigation 5 Geographical Observations 6 Flags 10 Town information Kota Kinabalu 11 Sandakan 22 Tawau 25 Kudat 27 Labuan 31 Sabah Rivers Kinabatangan 34 Klias 37 Tadian 39 Pura Pura 40 Maraup 41 Anchorages 42 2 Sabah is one of the 13 Malaysian states and with Sarawak, lies on the northern side of the island of Borneo, between the Sulu and South China Seas. Sabah and Sarawak cover the northern coast of the island. The lower two‐thirds of Borneo is Kalimantan, which belongs to Indonesia. The area has a fascinating history, and probably because it is on one of the main trade routes through South East Asia, Borneo has had many masters. Sabah and Sarawak were incorporated into the Federation of Malaysia in 1963 and Malaysia is now regarded a safe and orderly Islamic country. Sabah has a diverse ethnic population of just over 3 million people with 32 recognised ethnic groups. The largest of these is the Malays (these include the many different cultural groups that originally existed in their own homeland within Sabah), Chinese and “non‐official immigrants” (mainly Filipino and Indonesian). In recent centuries piracy was common here, but it is now generally considered relatively safe for cruising. However, the nearby islands of Southern Philippines have had some problems with militant fundamentalist Muslim groups – there have been riots and violence on Mindanao and the Tawi Tawi Islands and isolated episodes of kidnapping of people from Sabah in the past 10 years or so. -

Nesting Incidence, Exploitation and Trade Dynamics of Sea Turtles in Balabac Strait Marine Biodiversity Conservation Corridor, Palawan, Philippines

Nesting incidence, exploitation and trade dynamics of sea turtles in Balabac Strait Marine Biodiversity Conservation Corridor, Palawan, Philippines Rene Abdulhamed S. Antonio 1,2 and Joie D. Matillano 1,3 1College of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences Western Philippines University Puerto Princesa Campus Sta. Monica, Puerto Princesa City, Palawan, Philippines 2Present Office Address: Katala Foundation Inc. Puerto Princesa City, Philippines 3Present Office Address: Local Government of Taytay, Palawan, Philippines ABSTRACT The study assessed the nesting incidence, threats to nesting habitats, exploitation and trade dynamics of sea turtles in the Balabac Strait Marine Biodiversity Conservation Corridor (MBCC). The most number of nests found belonged to the green sea turtle Chelonia mydas and only very few were of hawksbill sea turtle Eretmochelys imbricata. The shoreline vegetation was the most preferred nesting area, followed by beach forest and open beach. The eggs and meat of sea turtles in Balabac Strait MBCC are exploited for local consumption and trade. Information on trade route and local perception on conservation issues about sea turtles is also presented herein. Keywords: Balabac Strait, exploitation, nesting incidence, sea turtle, trade dynamics INTRODUCTION In 2004, the Conservation International-Philippines (CI-P) declared Balabac Strait as a Conservation Priority Area (CPA) for the presence of several threatened species of vertebrates, particularly sea turtles (Anda and Tabangay-Baldera 2004). In that same year, Torres et al. (2004) together with the Exercise Luzon Sea Team conducted a rapid site assessment in several islands in Balabac Strait including Secam, Roughton and Candaraman Islands. Based on this survey, it was confirmed that there were hawksbill turtle Eretmochelys imbricata nests in Roughton Island. -

Spratly Islands

R i 120 110 u T4-Y5 o Ganzhou Fuqing n h Chenzhou g Haitan S T2- J o Dao Daojiang g T3 S i a n Putian a i a n X g i Chi-lung- Chuxiong g n J 21 T6 D Kunming a i Xingyi Chang’an o Licheng Xiuyu Sha Lung shih O J a T n Guilin T O N pa Longyan T7 Keelung n Qinglanshan H Na N Lecheng T8 T1 - S A an A p Quanzhou 22 T'ao-yüan Taipei M an T22 I L Ji S H Zhongshu a * h South China Sea ng Hechi Lo-tung Yonaguni- I MIYAKO-RETTO S K Hsin-chu- m c Yuxi Shaoguan i jima S A T21 a I n shih Suao l ) Zhangzhou Xiamen c e T20 n r g e Liuzhou Babu s a n U T Taichung e a Quemoy p i Meizhou n i Y o J YAEYAMA-RETTO a h J t n J i Taiwan C L Yingcheng K China a a Sui'an ( o i 23 n g u H U h g n g Fuxing T'ai- a s e i n Strait Claimed Straight Baselines Kaiyuan H ia Hua-lien Y - Claims in the Paracel and Spratly Islands Bose J Mai-Liao chung-shih i Q J R i Maritime Lines u i g T9 Y h e n e o s ia o Dongshan CHINA u g B D s Tropic of Cancer J Hon n Qingyuan Tropic of Cancer Established maritime boundary ian J Chaozhou Makung n Declaration of the People’s Republic of China on the Baseline of the Territorial Sea, May 15, 1996 g i Pingnan Heyuan PESCADORES Taiwan a Xicheng an Wuzhou 21 25° 25.8' 00" N 119° 56.3' 00" E 31 21° 27.7' 00" N 112° 21.5' 00" E 41 18° 14.6' 00" N 109° 07.6' 00" E While Bandar Seri Begawan has not articulated claims to reefs in the South g Jieyang Chaozhou 24 T19 N BRUNEI Claim line Kaihua T10- Hsi-yü-p’ing Chia-i 22 24° 58.6' 00" N 119° 28.7' 00" E 32 19° 58.5' 00" N 111° 16.4' 00" E 42 18° 19.3' 00" N 108° 57.1' 00" E China Sea (SCS), since 1985 the Sultanate has claimed a continental shelf Xinjing Guiping Xu Shantou T11 Yü Luxu n Jiang T12 23 24° 09.7' 00" N 118° 14.2' 00" E 33 19° 53.0' 00" N 111° 12.8' 00" E 43 18° 30.2' 00" N 108° 41.3' 00" E X Puning T13 that extends beyond these features to a hypothetical median with Vietnam. -

Wp19cover Copy

YUSOF ISHAK NALANDA-SRIWIJAYA CENTRE INSTITUTE WORKING PAPER SERIES NO. 19 EARLY VOYAGING IN THE SOUTH CHINA SEA: IMPLICATIONS ON TERRITORIAL CLAIMS The clipper Taeping under full sail. Photograph of a painting by Allan C. Green 1925 [public domain]. Credit: State Library of Victoria. Michael Flecker YUSOF ISHAK INSTITUTE NALANDA-SRIWIJAYA CENTRE WORKING PAPER SERIES NO. 19 (Aug 2015) EARLY VOYAGING IN THE SOUTH CHINA SEA: IMPLICATIONS ON TERRITORIAL CLAIMS Michael Flecker Michael Flecker has 28 years of experience in searching for and archaeologically excavating ancient shipwrecks, specialising in the evolution and interaction of various Asian shipbuilding traditions. In 2002 he received a PhD from the National University of Singapore based on his excavation of the 10th century Intan Wreck in Indonesia. His thesis was published as a book by the British Archaeological Report Series (2002). Other works include the book, Porcelain from the Vung Tau Wreck (2001), contributions to Shipwrecked: Tang Treasures and Monsoon Winds (2010) and Southeast Asian Ceramics: New Light on Old Pottery (2009), as well as numerous articles in the International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, the Mariner's Mirror and World Archaeology. Email: mdfl[email protected] The NSC Working Paper Series is published Citations of this electronic publication should be electronically by the Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre of made in the following manner: ISEAS - Yusok Ishak Institute Michael Flecker, Early Voyaging in the South China Sea: Implications on Territorial Claims, © Copyright is held by the author or authors of each Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre Working Paper No Working Paper. 19 (Aug 2015). NSC WPS Editors: NSC Working Papers cannot be republished, reprinted, or Andrea Acri Terence Chong Joyce Zaide reproduced in any format without the permission of the paper’s author or authors. -

Re-Framing the South China Sea: Geographical Reality and Historical Fact and Fiction

Re-framing the South China Sea: Geographical Reality and Historical Fact and Fiction Vivian Louis Forbes Universiti Brunei Darussalam Working Paper No.33 Institute of Asian Studies, Universiti Brunei Darussalam Gadong 2017 Editorial Board, Working Paper Series Professor Lian Kwen Fee, Institute of Asian Studies, Universiti Brunei Darussalam. Dr. Koh Sin Yee, Institute of Asian Studies, Universiti Brunei Darussalam. Author Dr Forbes is an Adjunct Research Professor at the National Institute for South China Sea Studies, Haikou; a Distinguished Research Fellow and Guest Professor at the China Institute of Boundary and Ocean Studies, Wuhan University; a Senior Visiting Research Fellow with the Maritime Institute of Malaysia since 1993; and an Adjunct Professor at the University of Western Australia. Contact: [email protected] The Views expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute of Asian Studies or the Universiti Brunei Darussalam. © Copyright is held by the author(s) of each working paper; no part of this publication may be republished, reprinted or reproduced in any form without permission of the paper’s author(s). 2 Re-framing the South China Sea: Geographical Reality and Historical Fact and Fiction Vivian Louis Forbes Abstract: The ‘labyrinth of detachable shoals’ in the South China Sea presented mariners during the late- 18th and early-19th centuries with a maritime area of considerable hazard that was best avoided. These same marine features now not only pose a problem for safe navigation within the South China Sea basin but have also challenged the minds of lawyers and politicians since the early- 1980s. -

Maps of Pleistocene Sea Levels in Southeast Asia: Shorelines, River Systems and Time Durations Harold K

^ Journal of Biogeography, 27, I 153-l I67 , Maps of Pleistocene sea levels in Southeast Asia: shorelines, river systems and time durations Harold K. Voris Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, Illinois, USA Abstract Aim Glaciation and deglaciation and the accompanying lowering and rising of sealevels during the late Pleistoceneare known to have greatly affected land massconfigurations in SoutheastAsia. The objective of this report is to provide a seriesof mapsthat estimatethe areasof exposed land in the Indo-Australian region during periods of the Pleistocenewhen sealevels were below present day levels. Location The maps presentedhere cover tropical SoutheastAsia and Austral-Asia. The east-westcoverage extends 8000 km from Australia to Sri Lanka. The north-south coverage extends 5000 km from Taiwan to Australia. Methods Present-day bathymetric depth contours were used to estimate past shore lines and the locations of the major drowned river systemsof the Sunda and Sahul shelves. The timing of sea level changesassociated with glaciation over the past 250,000 years was taken from multiple sourcesthat, in some cases,account for tectonic uplift and sub- sidenceduring the period in question. Results This report provides a seriesof maps that estimate the areasof exposed land in the Indo-Australian region during periods of 17,000, 150,000 and 250,000 years before present. The ancient shorelinesare basedon present day depth contours of 10, 20, 30, 40,50,75, 100 and 120 m. On the maps depicting shorelinesat 75,100 and 120 m below present levels the major Pleistoceneriver systemsof the Sunda and Sahul shelves are depicted. Estimatesof the number of major sealevel fluctuation events and the duration of time that sealevels were at or below the illustrated level are provided. -

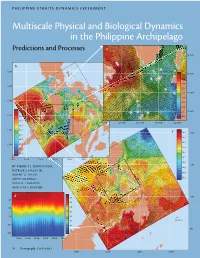

Multiscale Physical and Biological Dynamics in the Philippine Archipelago Predictions and Processes a 12°30’N

PHILIppINE STRAITS DYNAMICS EXPERIMENT Multiscale Physical and Biological Dynamics in the Philippine Archipelago Predictions and Processes a 12°30’N b 15°N 28.5 12°00’N 28.2 27.9 14°N 27.6 27.3 11°30’N 27.0 13°N 26.7 26.4 28.5 26.1 11°00’N 12°N 28.2 25.8 27.9 120°00’E 120°30’E 121°00’E 121°30’E 122°00’E 27.6 11°N 27.3 c 29.7 20°N 27.0 29.0 26.7 28.3 10°N 26.4 27.6 26.1 25.8 26.9 26.2 118°E 119°E 120°E 121°E 122°E 123°E 124°E 25.5 15°N BY PIERRE F.J. LERMUSIAUX, 24.8 PATRICK J. HALEY JR., 24.0 WAYNE G. LESLIE, 23.4 ARPIT AgARWAL, OLEG G. LogUTov, AND LISA J. BURTon d 28 10°N -50 26 24 -100 22 -150 20 -1 18 40 cm s -200 16 5°N 14 -250 06Feb 11Feb 16Feb 21Feb 26Feb 03Mar 70 Oceanography | Vol.24, No.1 115°E 120°E 125°E 130°E ABSTRACT. The Philippine Archipelago is remarkable because of its complex of which are known to be among the geometry, with multiple islands and passages, and its multiscale dynamics, from the strongest in the world (e.g., Apel et al., large-scale open-ocean and atmospheric forcing, to the strong tides and internal 1985). The purpose of the present study waves in narrow straits and at steep shelfbreaks. -

Patterns of Coral Species Richness and Reef Connectivity in Malaysia Issue Date: 2016-11-22

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/44304 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation Author: Waheed, Zarinah Title: Patterns of coral species richness and reef connectivity in Malaysia Issue Date: 2016-11-22 Patterns of coral species richness and reef connectivity in Malaysia Waheed, Z. Patterns of coral species richness and reef connectivity in Malaysia PhD thesis, Leiden University Cover design: Yee Wah Lau Printed by: Gildeprint, Enschede ISBN: 978 94 6233 460 1 © 2016 by Z. Waheed, all rights reserved. Funding. This thesis was accomplished with financial support from the Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia, with additional support from Universiti Malaysia Sabah, WWF-Malaysia, the A.M. Buitendijkfonds, and TREUB-maatschappij (Society for the Advancement of Research in the Tropics). Disclaimer. Following the recommendation of Article 8.2 of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, I declare that this publication is not issued for public and permanent scientific record, or for purposes of zoological nomenclature, and therefore not published within the meaning of the Code. Patterns of coral species richness and reef connectivity in Malaysia Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden, op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof. mr. C.J.J.M. Stolker, volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties te verdedigen op dinsdag 22 november 2016 klokke 13:45 door Zarinah Waheed geboren te Kota Kinabalu, Maleisië in 1978 Promotiecommissie Prof. dr. L.M. Chou (National University of Singapore, Singapore) Prof. dr. M. Schilthuizen (Universiteit Leiden & Naturalis Biodiversity Center) Prof. dr. H.P. Spaink (Universiteit Leiden) Prof. -

The Mountain Bird Fauna of Palawan, Philippine Islands" by FINN SALOMONSEN

129 The Mountain Bird Fauna of Palawan, Philippine Islands" By FINN SALOMONSEN NOONA DAN PAPERS No.Z The mountains of Palawan had never been explored, and its fauna and flora was completely unknown when the commit tee of the Danish "NooNA DAN Expedition" decided to carry out an investigation of Palawan, including a visit to the mountains of the interior. A short narrative of the sojourn of the NooNA DAN Expedition in the mountains has been given by me in a previous paper (SALOMONSEN, 1961, Dansk Ornith. Foren. Tidsskr., vol. 55, p. 219). Hitherto no mountain hirds were known from Palawan, but as a result of the NooN.A. DAN Expedition it is now possible to state that the following true mountain hirds are found in the island: Zostero ps montana Muscicapa westermanni Seicercus montis Phylloscopus triuirgatus Orthotomus cucullatus Stachyris hypogrammica These hirds are all restricted to the mountain forests above 900-1000 meters and are quite unknown at lower altitudes. They are all new to Palawan, although a single specimen of Seicercus montis had been collected as far back as in 1887, but the species has never been met with since then. Compared with the highlands of Borneo and Luzon, which abound in endemic species, the mountains of Palawan have a very poor bird fauna. This was predicted long ago by WmTEHEAD (1890, Ibis, ser. 6, vol. 2, p. 39), who said: "I should rather doubt if anisland like Palawan, which has no land above 6000 feet in altitude, has a very numerous highland fauna". It must be assumed, however, that the mountain fauna comprises a few other species than those discovered during the rather short stay 9 130 of the NooNA DAN Expedition. -

Modeled Connectivity of Acropora Millepora Populations from Reefs of the Spratly Islands and the Greater South China Sea

Coral Reefs (2016) 35:169–179 DOI 10.1007/s00338-015-1354-3 REPORT Modeled connectivity of Acropora millepora populations from reefs of the Spratly Islands and the greater South China Sea 1 2 3,4 Jeffrey G. Dorman • Frederic S. Castruccio • Enrique N. Curchitser • 2 1 Joan A. Kleypas • Thomas M. Powell Received: 11 September 2014 / Accepted: 14 September 2015 / Published online: 25 September 2015 Ó Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2015 Abstract The Spratly Island archipelago is a remote on other reefs. Examination of particle dispersal without network of coral reefs and islands in the South China Sea biology (settlement and mortality) suggests that larval that is a likely source of coral larvae to the greater region, connectivity is possible throughout the South China Sea but about which little is known. Using a particle-tracking and into the Coral Triangle region. Strong differences in model driven by oceanographic data from the Coral Tri- the spring versus fall larval connectivity and dispersal angle region, we simulated both spring and fall spawning highlight the need for a greater understanding of spawning events of Acropora millepora, a common coral species, dynamics of the region. This study confirms that the over a 46-yr period (1960–2005). Simulated population Spratly Islands are likely an important source of larvae for biology of A. millepora included the acquisition and loss of the South China Sea and Coral Triangle region. competency, settlement over appropriate benthic habitat, and mortality based on experimental data. The simulations Keywords Larval connectivity Á Coral reefs Á Individual- aimed to provide insights into the connectivity of reefs based modeling Á Coral Triangle Á South China Sea within the Spratly Islands, the settlement of larvae on reefs of the greater South China Sea, and the potential dispersal range of reef organisms from the Spratly Islands. -

Patterns of Coral Species Richness and Reef Connectivity in Malaysia

Patterns of coral species richness and reef connectivity in Malaysia Waheed, Z. Patterns of coral species richness and reef connectivity in Malaysia PhD thesis, Leiden University Cover design: Yee Wah Lau Printed by: Gildeprint, Enschede ISBN: 978 94 6233 460 1 © 2016 by Z. Waheed, all rights reserved. Funding. This thesis was accomplished with financial support from the Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia, with additional support from Universiti Malaysia Sabah, WWF-Malaysia, the A.M. Buitendijkfonds, and TREUB-maatschappij (Society for the Advancement of Research in the Tropics). Disclaimer. Following the recommendation of Article 8.2 of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, I declare that this publication is not issued for public and permanent scientific record, or for purposes of zoological nomenclature, and therefore not published within the meaning of the Code. Patterns of coral species richness and reef connectivity in Malaysia Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden, op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof. mr. C.J.J.M. Stolker, volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties te verdedigen op dinsdag 22 november 2016 klokke 13:45 door Zarinah Waheed geboren te Kota Kinabalu, Maleisië in 1978 Promotiecommissie Prof. dr. L.M. Chou (National University of Singapore, Singapore) Prof. dr. M. Schilthuizen (Universiteit Leiden & Naturalis Biodiversity Center) Prof. dr. H.P. Spaink (Universiteit Leiden) Prof. dr. P.C. van Welzen (Universiteit Leiden & Naturalis Biodiversity Center) Dr. F. Benzoni (University of Milano-Bicoca, Italy) Dr. C.H.J.M. Fransen (Naturalis Biodiversity Center) Promoter Prof. dr. E. Gittenberger (Universiteit Leiden & Naturalis Biodiversity Center) Copromoter Dr.