Introduction of Control Unit and Its Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

18-447 Computer Architecture Lecture 6: Multi-Cycle and Microprogrammed Microarchitectures

18-447 Computer Architecture Lecture 6: Multi-Cycle and Microprogrammed Microarchitectures Prof. Onur Mutlu Carnegie Mellon University Spring 2015, 1/28/2015 Agenda for Today & Next Few Lectures n Single-cycle Microarchitectures n Multi-cycle and Microprogrammed Microarchitectures n Pipelining n Issues in Pipelining: Control & Data Dependence Handling, State Maintenance and Recovery, … n Out-of-Order Execution n Issues in OoO Execution: Load-Store Handling, … 2 Reminder on Assignments n Lab 2 due next Friday (Feb 6) q Start early! n HW 1 due today n HW 2 out n Remember that all is for your benefit q Homeworks, especially so q All assignments can take time, but the goal is for you to learn very well 3 Lab 1 Grades 25 20 15 10 5 Number of Students 0 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 n Mean: 88.0 n Median: 96.0 n Standard Deviation: 16.9 4 Extra Credit for Lab Assignment 2 n Complete your normal (single-cycle) implementation first, and get it checked off in lab. n Then, implement the MIPS core using a microcoded approach similar to what we will discuss in class. n We are not specifying any particular details of the microcode format or the microarchitecture; you can be creative. n For the extra credit, the microcoded implementation should execute the same programs that your ordinary implementation does, and you should demo it by the normal lab deadline. n You will get maximum 4% of course grade n Document what you have done and demonstrate well 5 Readings for Today n P&P, Revised Appendix C q Microarchitecture of the LC-3b q Appendix A (LC-3b ISA) will be useful in following this n P&H, Appendix D q Mapping Control to Hardware n Optional q Maurice Wilkes, “The Best Way to Design an Automatic Calculating Machine,” Manchester Univ. -

The Von Neumann Computer Model 5/30/17, 10:03 PM

The von Neumann Computer Model 5/30/17, 10:03 PM CIS-77 Home http://www.c-jump.com/CIS77/CIS77syllabus.htm The von Neumann Computer Model 1. The von Neumann Computer Model 2. Components of the Von Neumann Model 3. Communication Between Memory and Processing Unit 4. CPU data-path 5. Memory Operations 6. Understanding the MAR and the MDR 7. Understanding the MAR and the MDR, Cont. 8. ALU, the Processing Unit 9. ALU and the Word Length 10. Control Unit 11. Control Unit, Cont. 12. Input/Output 13. Input/Output Ports 14. Input/Output Address Space 15. Console Input/Output in Protected Memory Mode 16. Instruction Processing 17. Instruction Components 18. Why Learn Intel x86 ISA ? 19. Design of the x86 CPU Instruction Set 20. CPU Instruction Set 21. History of IBM PC 22. Early x86 Processor Family 23. 8086 and 8088 CPU 24. 80186 CPU 25. 80286 CPU 26. 80386 CPU 27. 80386 CPU, Cont. 28. 80486 CPU 29. Pentium (Intel 80586) 30. Pentium Pro 31. Pentium II 32. Itanium processor 1. The von Neumann Computer Model Von Neumann computer systems contain three main building blocks: The following block diagram shows major relationship between CPU components: the central processing unit (CPU), memory, and input/output devices (I/O). These three components are connected together using the system bus. The most prominent items within the CPU are the registers: they can be manipulated directly by a computer program. http://www.c-jump.com/CIS77/CPU/VonNeumann/lecture.html Page 1 of 15 IPR2017-01532 FanDuel, et al. -

A 4.7 Million-Transistor CISC Microprocessor

Auriga2: A 4.7 Million-Transistor CISC Microprocessor J.P. Tual, M. Thill, C. Bernard, H.N. Nguyen F. Mottini, M. Moreau, P. Vallet Hardware Development Paris & Angers BULL S.A. 78340 Les Clayes-sous-Bois, FRANCE Tel: (+33)-1-30-80-7304 Fax: (+33)-1-30-80-7163 Mail: [email protected] Abstract- With the introduction of the high range version of parallel multi-processor architecture. It is used in a family of the DPS7000 mainframe family, Bull is providing a processor systems able to handle up to 24 such microprocessors, which integrates the DPS7000 CPU and first level of cache on capable to support 10 000 simultaneously connected users. one VLSI chip containing 4.7M transistors and using a 0.5 For the development of this complex circuit, a system level µm, 3Mlayers CMOS technology. This enhanced CPU has design methodology has been put in place, putting high been designed to provide a high integration, high performance emphasis on high-level verification issues. A lot of home- and low cost systems. Up to 24 such processors can be made CAD tools were developed, to meet the stringent integrated in a single system, enabling performance levels in performance/area constraints. In particular, an integrated the range of 850 TPC-A (Oracle) with about 12 000 Logic Synthesis and Formal Verification environment tool simultaneously active connections. The design methodology has been developed, to deal with complex circuitry issues involved massive use of formal verification and symbolic and to enable the designer to shorten the iteration loop layout techniques, enabling to reach first pass right silicon on between logical design and physical implementation of the several foundries. -

Embedded Multi-Core Processing for Networking

12 Embedded Multi-Core Processing for Networking Theofanis Orphanoudakis University of Peloponnese Tripoli, Greece [email protected] Stylianos Perissakis Intracom Telecom Athens, Greece [email protected] CONTENTS 12.1 Introduction ............................ 400 12.2 Overview of Proposed NPU Architectures ............ 403 12.2.1 Multi-Core Embedded Systems for Multi-Service Broadband Access and Multimedia Home Networks . 403 12.2.2 SoC Integration of Network Components and Examples of Commercial Access NPUs .............. 405 12.2.3 NPU Architectures for Core Network Nodes and High-Speed Networking and Switching ......... 407 12.3 Programmable Packet Processing Engines ............ 412 12.3.1 Parallelism ........................ 413 12.3.2 Multi-Threading Support ................ 418 12.3.3 Specialized Instruction Set Architectures ....... 421 12.4 Address Lookup and Packet Classification Engines ....... 422 12.4.1 Classification Techniques ................ 424 12.4.1.1 Trie-based Algorithms ............ 425 12.4.1.2 Hierarchical Intelligent Cuttings (HiCuts) . 425 12.4.2 Case Studies ....................... 426 12.5 Packet Buffering and Queue Management Engines ....... 431 399 400 Multi-Core Embedded Systems 12.5.1 Performance Issues ................... 433 12.5.1.1 External DRAMMemory Bottlenecks ... 433 12.5.1.2 Evaluation of Queue Management Functions: INTEL IXP1200 Case ................. 434 12.5.2 Design of Specialized Core for Implementation of Queue Management in Hardware ................ 435 12.5.2.1 Optimization Techniques .......... 439 12.5.2.2 Performance Evaluation of Hardware Queue Management Engine ............. 440 12.6 Scheduling Engines ......................... 442 12.6.1 Data Structures in Scheduling Architectures ..... 443 12.6.2 Task Scheduling ..................... 444 12.6.2.1 Load Balancing ................ 445 12.6.3 Traffic Scheduling ................... -

Demystifying Internet of Things Security Successful Iot Device/Edge and Platform Security Deployment — Sunil Cheruvu Anil Kumar Ned Smith David M

Demystifying Internet of Things Security Successful IoT Device/Edge and Platform Security Deployment — Sunil Cheruvu Anil Kumar Ned Smith David M. Wheeler Demystifying Internet of Things Security Successful IoT Device/Edge and Platform Security Deployment Sunil Cheruvu Anil Kumar Ned Smith David M. Wheeler Demystifying Internet of Things Security: Successful IoT Device/Edge and Platform Security Deployment Sunil Cheruvu Anil Kumar Chandler, AZ, USA Chandler, AZ, USA Ned Smith David M. Wheeler Beaverton, OR, USA Gilbert, AZ, USA ISBN-13 (pbk): 978-1-4842-2895-1 ISBN-13 (electronic): 978-1-4842-2896-8 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4842-2896-8 Copyright © 2020 by The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this book are included in the book’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. -

Reverse Engineering X86 Processor Microcode

Reverse Engineering x86 Processor Microcode Philipp Koppe, Benjamin Kollenda, Marc Fyrbiak, Christian Kison, Robert Gawlik, Christof Paar, and Thorsten Holz, Ruhr-University Bochum https://www.usenix.org/conference/usenixsecurity17/technical-sessions/presentation/koppe This paper is included in the Proceedings of the 26th USENIX Security Symposium August 16–18, 2017 • Vancouver, BC, Canada ISBN 978-1-931971-40-9 Open access to the Proceedings of the 26th USENIX Security Symposium is sponsored by USENIX Reverse Engineering x86 Processor Microcode Philipp Koppe, Benjamin Kollenda, Marc Fyrbiak, Christian Kison, Robert Gawlik, Christof Paar, and Thorsten Holz Ruhr-Universitat¨ Bochum Abstract hardware modifications [48]. Dedicated hardware units to counter bugs are imperfect [36, 49] and involve non- Microcode is an abstraction layer on top of the phys- negligible hardware costs [8]. The infamous Pentium fdiv ical components of a CPU and present in most general- bug [62] illustrated a clear economic need for field up- purpose CPUs today. In addition to facilitate complex and dates after deployment in order to turn off defective parts vast instruction sets, it also provides an update mechanism and patch erroneous behavior. Note that the implementa- that allows CPUs to be patched in-place without requiring tion of a modern processor involves millions of lines of any special hardware. While it is well-known that CPUs HDL code [55] and verification of functional correctness are regularly updated with this mechanism, very little is for such processors is still an unsolved problem [4, 29]. known about its inner workings given that microcode and the update mechanism are proprietary and have not been Since the 1970s, x86 processor manufacturers have throughly analyzed yet. -

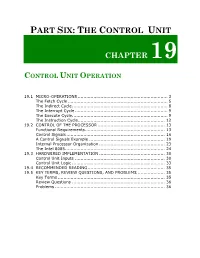

Control Unit Operation

PART SIX: THE CONTROL UNIT CHAPTER 19 CONTROL UNIT OPERATION 19.1 MICRO-OPERATIONS ............................................................... 3 The Fetch Cycle ...................................................................... 5 The Indirect Cycle................................................................... 8 The Interrupt Cycle ................................................................. 9 The Execute Cycle................................................................... 9 The Instruction Cycle............................................................. 12 19.2 CONTROL OF THE PROCESSOR ............................................... 13 Functional Requirements........................................................ 13 Control Signals ..................................................................... 16 A Control Signals Example ..................................................... 19 Internal Processor Organization .............................................. 23 The Intel 8085...................................................................... 24 19.3 HARDWIRED IMPLEMENTATION .............................................. 30 Control Unit Inputs ............................................................... 30 Control Unit Logic ................................................................. 33 19.4 RECOMMENDED READING ...................................................... 35 19.5 KEY TERMS, REVIEW QUESTIONS, AND PROBLEMS ................... 35 Key Terms .......................................................................... -

IBM Z Connectivity Handbook

Front cover IBM Z Connectivity Handbook Octavian Lascu John Troy Anna Shugol Frank Packheiser Kazuhiro Nakajima Paul Schouten Hervey Kamga Jannie Houlbjerg Bo XU Redbooks IBM Redbooks IBM Z Connectivity Handbook August 2020 SG24-5444-20 Note: Before using this information and the product it supports, read the information in “Notices” on page vii. Twentyfirst Edition (August 2020) This edition applies to connectivity options available on the IBM z15 (M/T 8561), IBM z15 (M/T 8562), IBM z14 (M/T 3906), IBM z14 Model ZR1 (M/T 3907), IBM z13, and IBM z13s. © Copyright International Business Machines Corporation 2020. All rights reserved. Note to U.S. Government Users Restricted Rights -- Use, duplication or disclosure restricted by GSA ADP Schedule Contract with IBM Corp. Contents Notices . vii Trademarks . viii Preface . ix Authors. ix Now you can become a published author, too! . xi Comments welcome. xi Stay connected to IBM Redbooks . xi Chapter 1. Introduction. 1 1.1 I/O channel overview. 2 1.1.1 I/O hardware infrastructure . 2 1.1.2 I/O connectivity features . 3 1.2 FICON Express . 4 1.3 zHyperLink Express . 5 1.4 Open Systems Adapter-Express. 6 1.5 HiperSockets. 7 1.6 Parallel Sysplex and coupling links . 8 1.7 Shared Memory Communications. 9 1.8 I/O feature support . 10 1.9 Special-purpose feature support . 12 1.9.1 Crypto Express features . 12 1.9.2 Flash Express feature . 12 1.9.3 zEDC Express feature . 13 Chapter 2. Channel subsystem overview . 15 2.1 CSS description . 16 2.1.1 CSS elements . -

Introduction to Microcoded Implementation of a CPU Architecture

Introduction to Microcoded Implementation of a CPU Architecture N.S. Matloff, revised by D. Franklin January 30, 1999, revised March 2004 1 Microcoding Throughout the years, Microcoding has changed dramatically. The debate over simple computers vs complex computers once raged within the architecture community. In the end, the most popular microcoded computers survived for three reasons - marketshare, technological improvements, and the embracing of the principles used in simple computers. So the two eventually merged into one. To truly understand microcoding, one must understand why they were built, what they are, why they survived, and, finally, what they look like today. 1.1 Motivation Strictly speaking, the term architecture for a CPU refers only to \what the assembly language programmer" sees|the instruction set, addressing modes, and register set. For a given target architecture, i.e. the architecture we wish to build, various implementations are possible. We could have many different internal designs of the CPU chip, all of which produced the same effect, namely the same instruction set, addressing modes, etc. The different internal designs could then all be produced for the different models of that CPU, as in the familiar Intel case. The different models would have different speed capabilities, and probably different prices to the consumer. But the same machine languge program, say a .EXE file in the Intel/DOS case, would run on any CPU in the family. When desigining an instruction set architecture, there is a tradeoff between software and hardware. If you provide very few instructions, it takes more instructions to perform the same task, but the hardware can be very simple. -

The Microprogrammed Control Unit

The Microprogrammed Control Unit Up to this point, we have studied: 1. The microoperation sequence associated with each assembly language instruction 2. The control signals associated with those microoperations. 3. The use of combinational logic in the form of a signal generation tree to generate these control signals. We now consider another option for generating the control signals. This is the microprogramming option, in which representations of the control signals are stored in a micro–memory and read into a MBR (micro–memory buffer register) from whence they are issued. Consider the control signal PC B1. When this is asserted, the contents of the Program Counter are copied onto bus B1. The method of generating this signal has no effect on the action it takes. We have two options for generating each control signal: Hardwired: The signal is output from an AND gate Microprogrammed: The signal is output from a D flip–flop. Survey of Bus Usage and Other Control Signals In order to structure the micro–memory properly, we must tabulate the control signals used and arrange them by use: bus transfer, ALU operation, memory operation, etc. Option Bus 1 Bus 2 Bus 3 ALU Other 0 1 PC B1 1 B2 B3 PC tra1 L / R’ 2 MAR B1 – 1 B2 B3 MAR tra2 A 3 R B1 R B2 B3 R shift C 4 IR B1 MBR B2 B3 IR not READ 5 SP B1 IOD B2 B3 SP add WRITE 6 B3 MBR sub extend 7 B3 IOD and 0 RUN 8 B3 IOA or 9 xor Note the important option 0. -

Microprogramming: Basic Idea

5-45 Chapter 5—Processor Design—Advanced Topics Microprogramming: Basic Idea • Recall control sequence for 1-bus SRC Step Concrete RTN Control Sequence T0 MA ← PC: C ← PC + 4; PCout, MAin, INC4, Cin, Read ← ← T1 MD M[MA]: PC C; Cout, PCin, Wait T2 IR ← MD; MDout, IRin ← T3 A R[rb]; Grb, Rout, Ain ← T4 C A + R[rc]; Grc, Rout, ADD, Cin ← T5 R[ra] C; Cout, Gra, Rin, End • Control unit job is to generate the sequence of control signals • How about building a computer to do this? Computer Systems Design and Architecture by V. Heuring and H. Jordan © 1997 V. Heuring and H. Jordan 5-46 Chapter 5—Processor Design—Advanced Topics The Microcode Engine • A computer to generate control signals is much simpler than an ordinary computer • At the simplest, it just reads the control signals in order from a read-only memory • The memory is called the control store • A control store word, or microinstruction, contains a bit pattern telling which control signals are true in a specific step • The major issue is determining the order in which microinstructions are read Computer Systems Design and Architecture by V. Heuring and H. Jordan © 1997 V. Heuring and H. Jordan 5-47 Chapter 5—Processor Design—Advanced Topics Fig 5.16 Block Diagram of Microcoded Control Unit Ck CCs Other IR Opcode PLA • Microinstruction has Sequencer (computes branch control, 2 start addr) External source n branch address, and control signal fields Increment 4–1 Mux n • Microprogram µPC counter can be set n from several sources to do the required Control sequencing store k n m µBranch µIR control Branch Control signals address PCout, etc. -

A Characterization of Processor Performance in the VAX-1 L/780

A Characterization of Processor Performance in the VAX-1 l/780 Joel S. Emer Douglas W. Clark Digital Equipment Corp. Digital Equipment Corp. 77 Reed Road 295 Foster Street Hudson, MA 01749 Littleton, MA 01460 ABSTRACT effect of many architectural and implementation features. This paper reports the results of a study of VAX- llR80 processor performance using a novel hardware Prior related work includes studies of opcode monitoring technique. A micro-PC histogram frequency and other features of instruction- monitor was buiit for these measurements. It kee s a processing [lo. 11,15,161; some studies report timing count of the number of microcode cycles execute z( at Information as well [l, 4,121. each microcode location. Measurement ex eriments were performed on live timesharing wor i loads as After describing our methods and workloads in well as on synthetic workloads of several types. The Section 2, we will re ort the frequencies of various histogram counts allow the calculation of the processor events in 5 ections 3 and 4. Section 5 frequency of various architectural events, such as the resents the complete, detailed timing results, and frequency of different types of opcodes and operand !!Iection 6 concludes the paper. specifiers, as well as the frequency of some im lementation-s ecific events, such as translation bu h er misses. ?phe measurement technique also yields the amount of processing time spent, in various 2. DEFINITIONS AND METHODS activities, such as ordinary microcode computation, memory management, and processor stalls of 2.1 VAX-l l/780 Structure different kinds. This paper reports in detail the amount of time the “average’ VAX instruction The llf780 processor is composed of two major spends in these activities.