Introduction to the Unitarian and Universalist Traditions Andrea Greenwood and Mark W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SERMON: "FRANCIS DAVID and the EDICT of TORDA" Francis

SERMON: "FRANCIS DAVID AND THE EDICT OF TORDA" Francis David (Ferencz David) was born at Klausenburg in Kolozsvar, the capital of Transylvania, in 1510. He was the son of a shoemaker and of a deeply religious mother descended from a noble family. He was first educated at a local Franciscan school, then at Gyulafehervar, a Catholic seminary. His high intellectual ability led him to the University of Wittenburg, where he completed his education 1545-1548 (then in his thirties). He developed the ability to debate fluently in Hungarian, German and Latin. His years of study fall in the exciting period of the Reformation. Although he must have been aware of and perhaps influenced by the debates of the time, his first position was that of rector of a Catholic school in Beszterce. He studied Luthers writings and became a Protestant. Lutheranism had spread rapidly in Transylvania during his absence and he joined the new movement on his return, becoming pastor of a Lutheran church in Peterfalva. He took part in theological debates, proving himself a gifted and powerful orator and a clear thinker. His fame spread, and he was elected as a Superintendent or Bishop of the Lutheran Church. The Calvinist or Reformed movement was at the same time spreading across Transylvania, and Francis David studied its teachings. Its main difference from Lutheranism lay in its symbolical interpretation of the Lords Supper. Gradually convinced, he resigned his Lutheran bishopric in 1559 and joined the Calvinists as an ordinary minister. Again, his intellectual ability and his gifts of oratory bore him to leadership and he was elected Bishop of the Reformed Church of Transylvania. -

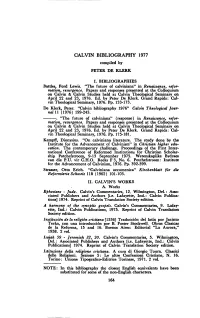

1977 Compiled by PETER DE KLERK

CALVIN BIBLIOGRAPHY 1977 compiled by PETER DE KLERK I. BIBLIOGRAPHIES Battles, Ford Lewis. "The future of calviniana" in Renaissance, refor mation, resurgence. Papers and responses presented at the Colloquium on Calvin & Calvin Studies held at Calvin Theological Seminary on April 22 and 23, 1976. Ed. by Peter De Klerk. Grand Rapids: Cal vin Theological Seminary, 1976. Pp. 133-173. De Klerk, Peter. "Calvin bibliography 1976" Calvin Theological Jour- nal U (1976) 199-243. -. "The future of calviniana" (response) in Renaissance, refor mation, resurgence. Papers and responses presented at the Colloquium on Calvin & Calvin Studies held at Calvin Theological Seminary on April 22 and 23, 1976. Ed. by Peter De Klerk. Grand Rapids: Cal vin Theological Seminary, 1976. Pp. 175-181. Kempff, Dionysius. "On calviniana literature. The study done by the Institute for the Advancement of Calvinism" in Christian higher edu cation. The contemporary challenge. Proceedings of the First Inter national Conference of Reformed Institutions for Christian Scholar ship Potchefstroom, 9-13 September 1975. Wetenskaplike Bydraes van die P.U. vir C.H.O. Reeks F 3, No. 6. Potchefstroom: Institute for the Advancement of Calvinism, 1976. Pp. 392-399. Strasser, Otto Erich. "Calviniana œcumenica" Kirchenblatt für die Reformierte Schweiz 118 (1962) 101-103. II. CALVIN'S WORKS A. Works Ephesians - Jude. Calvin's Commentaries, 12. Wilmington, Del.: Asso ciated Publishers and Authors [i.e. Lafayette, Ind.: Calvin Publica tions] 1974. Reprint of Calvin Translation Society edition. A harmony of the synoptic gospels. Calvin's Commentaries, 9. Lafay ette, Ind.: Calvin Publications, 1975. Reprint of Calvin Translation Society edition. Institución de la religion cristiana fi536] Traducción del latín por Jacinto Terán, con una introducción por Β. -

Arianism 1 Arianism

Arianism 1 Arianism "Arian" redirects here. For other uses, see Arian (disambiguation). Not to be confused with "Aryanism", which is a racial theory. Part of a series of articles on Arianism History and theology • Arius • Acacians • Anomoeanism • Arian controversy • First Council of Nicaea • Lucian of Antioch • Gothic Christianity Arian leaders • Acacius of Caesarea • Aëtius • Demophilus of Constantinople • Eudoxius of Antioch • Eunomius of Cyzicus • Eusebius of Caesarea • Eusebius of Nicomedia • Eustathius of Sebaste • George of Laodicea • Ulfilas Other Arians • Asterius the Sophist • Auxentius of Milan • Auxentius of Durostorum • Constantius II • Wereka and Batwin • Fritigern • Alaric I • Artemius • Odoacer • Theodoric the Great Modern semi-Arians • Samuel Clarke • Isaac Newton • William Whiston Opponents • Peter of Alexandria • Achillas of Alexandria Arianism 2 • Alexander of Alexandria • Hosius of Cordoba • Athanasius of Alexandria • Paul I of Constantinople Christianity portal • v • t [1] • e Arianism is the theological teaching attributed to Arius (c. AD 250–336), a Christian presbyter in Alexandria, Egypt, concerning the relationship of God the Father to the Son of God, Jesus Christ. Arius asserted that the Son of God was a subordinate entity to God the Father. Deemed a heretic by the Ecumenical First Council of Nicaea of 325, Arius was later exonerated in 335 at the regional First Synod of Tyre,[2] and then, after his death, pronounced a heretic again at the Ecumenical First Council of Constantinople of 381. The Roman Emperors Constantius II (337–361) and Valens (364–378) were Arians or Semi-Arians. The Arian concept of Christ is that the Son of God did not always exist, but was created by—and is therefore distinct from—God the Father. -

Chapter Thirty the Ottoman Empire, Judaism, and Eastern Europe to 1648

Chapter Thirty The Ottoman Empire, Judaism, and Eastern Europe to 1648 In the late fifteenth and the sixteenth centuries, while the Portuguese and Spanish explored the oceans and exploited faraway lands, the eastern Mediterranean was dominated by the Ottomans. Mehmed II had in 1453 taken Constantinople and made it his capital, putting an end to the Byzantine empire. The subsequent Islamizing of Constantinople was abrupt and forceful. Immediately upon taking the city, Mehmed set about to refurbish and enlarge it. The population had evidently declined to fewer than two hundred thousand by the time of the conquest but a century later was approximately half a million, with Muslims constituting a slight majority. Mehmed and his successors offered tax immunity to Muslims, as an incentive for them to resettle in the city. Perhaps two fifths of the population was still Christian in the sixteenth century, and a tenth Jewish (thousands of Jewish families resettled in Constantinople after their expulsion from Spain in 1492). The large and impressive churches of Constantinople were taken over and made into mosques. Most dramatically, Mehmed laid claim to Haghia Sophia, the enormous cathedral that for nine hundred years had been the seat of the patriarch of Constantinople, and ordered its conversion into a mosque. It was reconfigured and rebuilt (it had been in a state of disrepair since an earthquake in 1344), and minarets were erected alongside it. The Orthodox patriarch was eventually placed in the far humbler Church of St. George, in the Phanari or “lighthouse” district of Constantinople. Elsewhere in the city Orthodox Christians were left with relatively small and shabby buildings.1 Expansion of the Ottoman empire: Selim I and Suleiman the Magnificent We have followed - in Chapter 26 - Ottoman military fortunes through the reigns of Mehmed II (1451-81) and Bayezid II (1481-1512). -

Francis-David.Faith-And-Freedom-2.7

Francis David: Faith and Freedom By Rev. Steven A. Protzman February 7th, 2016 © February, 2016 First Reading: The Edict of Torda1 Second Reading: dive for dreams by ee cummings2 Sermon Unitarianism has existed in Romania for more than 350 years. Among its heroes is Francis David, court preacher for the only Unitarian king in history, John Sigismund. As we honor our Partner Church this weekend with the Festival of the First Bread and begin our month of Unitarian Universalist history, we will learn about the legacy of David and Unitarianism in Transylvania, which includes some of our fundamental UU values: freedom, reason and tolerance. Part I Today as begin our month of UU history, we celebrate the Festival of the First Bread and our relationship with a small Unitarian village in Romania, Janosfalva. Today we will tell a story about the beginnings of Unitarianism almost 450 years ago in Eastern Europe and Francis David, one of our Unitarian heroes. Of the many remarkable parts of this story, perhaps the most amazing part is that a tiny kingdom on the eastern edge of Europe, Transylvania, had freedom of religion in an age where, as UU minister Frank Schulman said, "“the Inquisition was crushing religious freedom, John Calvin and his cohorts burned heretics like Michael Servetus at the stake for daring to question doctrine, when Luther wrote, “Let heads roll in the streets,” and when the massacre of St. Bartholomew killed 30,000 Protestants in France".3 It was during this tumultuous time when the Reformation and the Radical Reformation were underway and the first information age, created by the invention of the printing press, was changing the world radically and rapidly that Francis David was born in 1510 in Kolosvar, Transylvania, the son of a shoemaker. -

The Pasha of Buda and the Edict of Torda

1 Children of the Same God: Unitarianism in Kinship with Judaism and Islam Minns Lectures, 2009 Rev. Dr. Susan Ritchie First Church Boston; Wednesday April 22, 2009 Lecture Two of the Series Children of the Same God: European Unitarianism in Creative Cultural Exchange with Ottoman Islam1 When Sultan Suleyman of the Ottoman Empire first learned of the birth of John Sigismund, the son of the King of Hungary, he felt it be such an important event that he sent a personal representative to stand in a corner of Queen Isabella’s room to watch over her and the infant.2 Sigismund’s father, King John Zapolya , King of Hungary and Viovode of Transylvania, had died just two weeks after his son’s birth that July of 1540. On his deathbed he had given instructions that his son be named heir to his titles, a violation of a previous agreement that promised Hungary after John’s death to Ferdinand, the brother of the Hapsburg Emperor Charles. When it became clear after John’s death that his successors had no intention of allowing Hungary to become a part of the Hapsburg Empire, Ferdinand responded by laying siege on Buda. In 1541, with Queen Isabella’s forces nearing collapse, Sultan Suleyman appeared in Buda with a large army, successfully repulsing Ferdinand. Suleyman claimed the capital of Buda and much of lower Hungary for his control while granting Isabella and her infant son Transylvania to rule independently, but under the ultimate control of the Ottoman State. After some years of political contrivance and redefinition, Transylvania developed into its new identity as a border state. -

Syllabus: Unitarianism in Transylvania Course ID: HS 4005 Instructor: Rev

Syllabus: Unitarianism in Transylvania Course ID: HS 4005 Instructor: Rev. Sándor Kovács PhD Associate Professor Protestant Theological Institute – Cluj/Kolozsvár [email protected] Course description Welcome to the Unitarianism in Transylvania course. This course will examine the history of the Unitarians in Transylvania and Central Eastern Europe from the development of the antitrinitarian movement to the last quarter of the 20th Century. The lecture-discussion course focuses on the ecclesiastical and political changes regarding Transylvanian Unitarianism. We will explore the history of Transylvania from the present days back to the previous centuries. Covering four centuries of history the participants will have the possibility to understand the religious and ethnical pluralism of the “land beyond the forests,” and the uniqueness of Unitarianism in Europe. Learning outcomes There are three purposes of this course: 1. to introduce the rich history of Transylvanian Unitarianism; 2. to show how “Transylvania” can challenge the way of thinking about religious leadership; 3. to deepen the relationship with Unitarian Universalists over the seas. Schedule Unit 1 (February 11) – Do we need to think alike? - The sentence is attributed to Francis David, what is behind it? - What do you know about Transylvania? If you have been there please bring items which connect you to Transylvania. - We are going to locate Transylvania on a map - The Unitarians living in Transylvania: numbers, statistics, maps - Parishes and districts. Congregational polity. Church governing policies - The Unitarian symbol – ways of interpretation, origin - Liturgy - Ministerial training Reading: No reading is required for the first meeting. Unit 2 (February 25)– Trauma or dilemma: the communist dictatorship - Cohabitate or collaborate for your survival? - What does “resistance” look like in a communist country - The risks of ministry - Communist strategies of repression - A Unitarian martyr mirror - Facing the past, problems of reconciliation Reading: Judit Gellérd: Prisoner of Liberté. -

Calvin's Tormentors Baker Academic, a Division of Baker Publishing Group, © 2018

C ALVIN’S TORMENTORS Understanding the Conflicts That Shaped the Reformer GARY W. JENKINS K Gary W. Jenkins, Calvin's Tormentors Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group, © 2018. Used by permission. _Jenkins_CalvinsTormentors_BKB_djm.indd 3 1/19/18 10:02 AM 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 © 2018 by Gary W. Jenkins Published by Baker Academic a division of Baker Publishing Group PO Box 6287, Grand Rapids, MI 49516-6287 www.bakeracademic.com Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—for example, electronic, photocopy, recording—without the prior written permission of the publisher. The only exception is brief quotations in printed reviews. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Jenkins, Gary W., 1961– author. Title: Calvin’s tormentors : understanding the conflicts that shaped the reformer / Gary W. Jenkins. Description: Grand Rapids : Baker Publishing Group, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2017052473 | ISBN 9780801098338 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Calvin, Jean, 1509–1564. | Reformation. Classification: LCC BX9418 .J46 2018 | DDC 284/.2092—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017052473 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Gary W. Jenkins, Calvin's Tormentors Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group, © 2018. Used by permission. _Jenkins_CalvinsTormentors_BKB_djm.indd 4 1/19/18 10:02 AM For Professors William J. Tighe and Gary R. Hafer, in gratitude for decades of friendship. -

Experiencing the Mystery

Out of the Flames Led by Rev. Steven A. Protzman February 2, 2014 Part I of a UU History Series First Reading: An excerpt from "Out of the Flames" by Lawrence and Nancy Goldstone1 Second Reading: "Sunrise" by Mary Oliver2 Out of the Flames By Steven A. Protzman © February, 2014 As the Protestant Reformation took hold in Europe and forever changed the course of western Christianity, an even more radical reformation was taking place, out of which Unitarianism in Poland and Transylvania would arise. It is a fascinating story that includes the invention of the printing press, the death by burning of proto-Unitarian Michael Servetus, and the rise of tolerance for diverse religious beliefs. There was a facebook post yesterday that asked: If someone from the 1500s suddenly appeared, what would be the most difficult thing to explain to them about modern life? The answer: I possess a device in my pocket that is capable of accessing every piece of information know to humankind but I use it to look at pictures of kittens and get into arguments with strangers. Earlier this week a member of this congregation asked me about today's sermon topic. When I told them it was about the rise of Unitarianism in Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries, they made a bet with me that I couldn't tie Pete Seeger into my sermon. I accepted of course! But before Seeger, a legendary American folk singer who died on Monday at the age of 94, makes his cameo appearance, we're going to take a journey of the imagination back to 16th century Europe. -

A History of Unitarianism: in Transylvania, England and America Volume II (1952)

A History of Unitarianism: In Transylvania, England and America Volume II (1952) This text was taken from a 1977 Beacon Press edition of Wilbur’s book and was made possible through the generous and kind permission of Earl Morse Wilbur’s family, with whom the copyright resides. PREFACE THE AUTHOR'S earlier work, A History of Unitarianism: Socinianism and Its Antecedents (Cambridge, 1945) was designed, though no indication was given in the preface or elsewhere, as the first of two volumes on the general subject. The present volume therefore is to be taken as the second or complementary volume of the work, and any cross-references to the former work are given as to Volume 1. The present book has been written with constant reference to available sources, and the author's obligation to various persons for valued help given still stand; but further acknowledgment is here made to Dr. Alexander Szent-Ivanyi, sometime Suffragan Bishop of the Unitarian Church in Hungary, who has carefully read the manuscript of the section on Transylvania and made sundry valued suggestions; to Dr. Herbert McLachlan, formerly Principal of the Unitarian College, Manchester, who has performed a like service for the chapters of the English section; and to Dr. Henry Wilder Foote for his constant interest and for unnumbered services of kindness in the course of the whole work I can not take my leave of a subject that has engaged my active interest for over forty-five years, and has furnished my chief occupation for the past fifteen years, without giving expression to the profound gratitude I feel that in spite of great difficulties and many interruptions I have been granted life and strength to carry my task through to completion. -

7. Augustine and Early Medieval Church

Augustine & Early Church who is the real Augustine? Legacy and Importance of Augustine Brian Stock, Augustine the Reader: Meditation, Self-Knowledge, and the Ethics of Interpretation (Belknap Press, 1996), Augustine's world is not only pre-print, it's pre-literate, emerging from a fundamentally oral culture where the rhetor reigns and the legacy of the bishop is his sermons, not his books. Finally, Augustine’s “world” is relatively small, circumscribed by boundaries of the empire. What could such a foreign voice have to say to us, in our post- modern, post-Christian, post-literate, globalized world? Worldview “Worldview” = v how one sees and interprets their reality , which is a particular context (time, place, culture). v philosophical view, all-encompassing perspective on everything that exists & matters to us. v most fundamental beliefs & assumptions about universe reflects answers to all “big questions” of human existence: about who & what we are, where we came from, why we’re here, where we’re headed, meaning & purpose of life, nature of afterlife, what counts as a good life here & now. Christians live in a particular time/place/culture but are led to see in a different way; thus, a Christian worldview is the goal; rooted in a Biblical worldview as much as possible. Legacy and Importance of Augustine James K.A. Smith, Prof. Philosophy Calvin College = 25 books ! (2019) On the Road with Saint Augustine: A Real-World Spirituality for Restless Hearts. “…when I think of the tireless bishop I think first and foremost of love. For Augustine, love is who we are. We are made to love, for love, and what we love is what defines us. -

Each According to Their Understanding1 Rev

Each According to Their Understanding1 Rev. Myke Johnson January 7, 2018 Allen Avenue Unitarian Universalist Church This month, January, 2018, marks the 450th anniversary of one of the first official statements of religious tolerance. Today we will explore this historic moment in Unitarianism, and its implications for our UU faith today. Time For All Ages: A Story Of Religious Freedom2 This is the text of a slideshow by Carolyn Barschow, Director of Religious Education Unitarian Universalist churches welcome people from all different religious backgrounds. In our Sanctuary, you could meet someone who follows the teachings of Jewish, Hindu, Christian, Buddhist or Pagan religion, just to name a few. You could also meet people who follow no religious tradition. That idea is part of our third principle – to accept each other AND our fourth principle – that people are free to search for what is true in life. Our city of Portland welcomes people from all different religious backgrounds. When you travel around town, you might notice many different churches, synagogues and temples. Your classmates at school might spend their weekend time in those buildings while you and your family come to Allen Avenue. That idea is part of the Bill of Rights of the whole United States, the first amendment says the government can make no laws that stop people from gathering to practice religion. In this church and in this country, we practice freedom of religion. Freedom of religion. What do you think that means? It may seem hard to believe, but freedom of religion was once a new idea! Can you imagine what it would be like to live without religious freedom? One time and place that new idea of religious freedom was born was 450 years ago - back in January of 1568- in the country known as Transylvania.