Roots in Europe, Part 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SERMON: "FRANCIS DAVID and the EDICT of TORDA" Francis

SERMON: "FRANCIS DAVID AND THE EDICT OF TORDA" Francis David (Ferencz David) was born at Klausenburg in Kolozsvar, the capital of Transylvania, in 1510. He was the son of a shoemaker and of a deeply religious mother descended from a noble family. He was first educated at a local Franciscan school, then at Gyulafehervar, a Catholic seminary. His high intellectual ability led him to the University of Wittenburg, where he completed his education 1545-1548 (then in his thirties). He developed the ability to debate fluently in Hungarian, German and Latin. His years of study fall in the exciting period of the Reformation. Although he must have been aware of and perhaps influenced by the debates of the time, his first position was that of rector of a Catholic school in Beszterce. He studied Luthers writings and became a Protestant. Lutheranism had spread rapidly in Transylvania during his absence and he joined the new movement on his return, becoming pastor of a Lutheran church in Peterfalva. He took part in theological debates, proving himself a gifted and powerful orator and a clear thinker. His fame spread, and he was elected as a Superintendent or Bishop of the Lutheran Church. The Calvinist or Reformed movement was at the same time spreading across Transylvania, and Francis David studied its teachings. Its main difference from Lutheranism lay in its symbolical interpretation of the Lords Supper. Gradually convinced, he resigned his Lutheran bishopric in 1559 and joined the Calvinists as an ordinary minister. Again, his intellectual ability and his gifts of oratory bore him to leadership and he was elected Bishop of the Reformed Church of Transylvania. -

TRANSYLVANIAN UNITARIANISM BIBLIOGRAPHY (Update 9/10/2014)—Compiled by Harold Babcock

TRANSYLVANIAN UNITARIANISM BIBLIOGRAPHY (update 9/10/2014)—compiled by Harold Babcock Allen, J. H. A Visit to Transylvania and the Consistory at Kolozvar. Boston: George H. Ellis, 1881. Ashton, Timothy W. “Transylvanian Unitarianism: Background and Theology in the Contemporary Situation of Communist Romania.” Manuscript of research paper, Meadville/Lombard Theological School, 1968. Balazs, Mihaly. Ference David. Bibliotheca Dissidentium: Repertoire des non‐conformistes religieux des seizieme et dis‐septiemesiecles/edite par Andre Seguenny. T. 26: Ungarlandische Antitrinitarier IV. Baden‐Baden; Bouxwiller: Koerner, 2008. [translated by Judit Gellerd] Balazs, Mihaly and Keseru, Gizella, eds. Gyorgy Enyedi and Central European Unitarianism in the 16th‐17th Centuries. Budapest: Balassi Kiedo, 1998. Boros, George, ed. Report of the International Unitarian Conference. Kolozsvart: Nyomatott Gambos Ferencznel, 1897. Campbell, Judy. “Here They Come! A Visit to Transylvania,”uu & me! Vol. 3 No. 3., December 1999: 2‐3. Cheetham, Henry H. Unitarianism and Universalism: An Illustrated History. Boston: Beacon Press, 1962. Codrescu, Andrei and Ross, Warren. “Rediscovering Our Transylvanian Connection: A Challenge and a Response,”World Magazine, July/August 1995: 24‐30. Cornish, Louis C., ed. The Religious Minorities in Transylvania. Boston: The Beacon Press, Inc., 1925. _____, ed. Transylvania in 1922. Boston: The Beacon Press, Inc., 1923. Erdo, Janos. “Light Upon Religious Toleration from Francis David and Transylvania,” Faith and Freedom 32, Part II (1979): 75‐82. _____. “The Biblicism of Ferenc David,” Faith and Freedom 48, Part I, (?): 44‐50. Erdo, John. “The Foundations of the Transylvanian Unitarian Church,” Faith and Freedom 23, Part II (1970): 61‐70. _____. Transylvanian Unitarian Church: Chronological History and Theological Essays. -

Liberty, Enlightenment, and the Polish Brethren

INTERCULTURAL RELATIONS ◦ RELACJE MIĘDZYKULTUROWE ◦ 2018 ◦ 2 (4) Jarosław Płuciennik1 LIBERTY, ENLIGHTENMENT, AND THE POLISH BRETHREN Abstract The article presents an overview of the history of the idea of dialogics and lib- erty of expression. This liberty is strictly tied to the problem of liberty of con- science. Since the 17th century, the development of the dialogics traveled from an apocalyptic – and demonising its opponents – discourse as in John Milton’s approach in Areopagitica, through dialogics of cooperation and obligations and laws (in the Polish Brethren, so-called Socinians, especially Jan Crell), through dialogics of deduction (transcendental deduction in Immanuel Kant), to dialog- ics of induction and creativity (John Stuart Mill). Key words: liberty of conscience, liberty of expression, Enlightenment, history of ideas, dialogue AREOPAGITICA BY JOHN MILTON AND THE APOCALYPTIC AND MARKET DIALOGICS (1644) The best starting point of my analysis is John Milton’s Areopagitica from 1644, which not only concerns liberty and freedom of speech, but also is the most famous and most extensive prose work of Milton, who has be- come world famous, above all, due to his poetry (Tazbir, 1973, p. 111). The text was published on November 23, 1644, without a license, with- out registration, without the identification of the publisher and printer, and was the first English text entirely devoted to freedom of speech and pub- lishing. The fact that responsibility was taken for the “free word” of the author, who allowed himself to be identified on the title page is critical. 1 Prof.; University of Lodz, Institute of Contemporary Culture, Faculty of Philology; e-mail: [email protected]. -

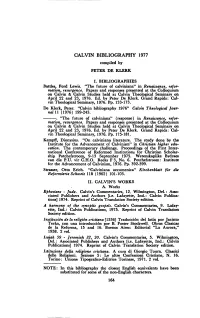

1977 Compiled by PETER DE KLERK

CALVIN BIBLIOGRAPHY 1977 compiled by PETER DE KLERK I. BIBLIOGRAPHIES Battles, Ford Lewis. "The future of calviniana" in Renaissance, refor mation, resurgence. Papers and responses presented at the Colloquium on Calvin & Calvin Studies held at Calvin Theological Seminary on April 22 and 23, 1976. Ed. by Peter De Klerk. Grand Rapids: Cal vin Theological Seminary, 1976. Pp. 133-173. De Klerk, Peter. "Calvin bibliography 1976" Calvin Theological Jour- nal U (1976) 199-243. -. "The future of calviniana" (response) in Renaissance, refor mation, resurgence. Papers and responses presented at the Colloquium on Calvin & Calvin Studies held at Calvin Theological Seminary on April 22 and 23, 1976. Ed. by Peter De Klerk. Grand Rapids: Cal vin Theological Seminary, 1976. Pp. 175-181. Kempff, Dionysius. "On calviniana literature. The study done by the Institute for the Advancement of Calvinism" in Christian higher edu cation. The contemporary challenge. Proceedings of the First Inter national Conference of Reformed Institutions for Christian Scholar ship Potchefstroom, 9-13 September 1975. Wetenskaplike Bydraes van die P.U. vir C.H.O. Reeks F 3, No. 6. Potchefstroom: Institute for the Advancement of Calvinism, 1976. Pp. 392-399. Strasser, Otto Erich. "Calviniana œcumenica" Kirchenblatt für die Reformierte Schweiz 118 (1962) 101-103. II. CALVIN'S WORKS A. Works Ephesians - Jude. Calvin's Commentaries, 12. Wilmington, Del.: Asso ciated Publishers and Authors [i.e. Lafayette, Ind.: Calvin Publica tions] 1974. Reprint of Calvin Translation Society edition. A harmony of the synoptic gospels. Calvin's Commentaries, 9. Lafay ette, Ind.: Calvin Publications, 1975. Reprint of Calvin Translation Society edition. Institución de la religion cristiana fi536] Traducción del latín por Jacinto Terán, con una introducción por Β. -

The Polish Baptist Identity in Historical Context

The Polish Baptist Identity Eistorical Context Thesis Presented to the Faculty of McMaster Divinity College in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Divinity by Jerzy Pawel Rogaczewski Hamilton, Ontario April, L995 nc|rAStEt UxlVl|ltltY UllAfl MASTER OF DIVINITY McMASTER UNIVERSITY Hamilton, Ontario The Polish Baptist Identity in Historical Context AUTHOR: Jerzy Pawel Rogaczewski SUPERVISOR: Rev. Dr. Witliam H. Bracknev NUMBER OF PAGES: 115 McMASTER DTVIMTY COLLEGE Upon the recommendation of an oral examination committee and vote of the facultv. this thesis-project by JERZY PAWEL ROGACZEWSKI is hereby accepted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF DTVIMTY Second Reader External Reader Date Apnl27, 7995 This thesis is dedicated to my father, Stefan Rogaczewski, a beloved Baptist leader in Poland. TABIJE OF CONTEIITS fntroduction ' 1 Cbapter I. uarry christiaJ.; ;;"r""" ; *" ltaking of A Ueritage . 5 Christian Origins in poland . 5 The Pre-Christian period in Poland . 5 Roman Catholic Influence 6 The Beginnings of Christianity in Poland 8 Pre-Reformation Catholic Church in Poland L4 The Protestant Reforrnation L7 Martin Luther L7 Huldrych Zwingli 18 John Calvin 19 The Anabaptist Movement 20 The Po1ish Reformation 2L The Dovnfall of polish protestantisn and the Victory of the Counter-Reformation . 2g Summary 30 Chapter fI. Tbe Beginnings of tbe naptist Movement in Poland........32 Baptist History from Great Britain to Europe 32 Origins of the Baptists in Great Britain 32 The Spread -

Arianism 1 Arianism

Arianism 1 Arianism "Arian" redirects here. For other uses, see Arian (disambiguation). Not to be confused with "Aryanism", which is a racial theory. Part of a series of articles on Arianism History and theology • Arius • Acacians • Anomoeanism • Arian controversy • First Council of Nicaea • Lucian of Antioch • Gothic Christianity Arian leaders • Acacius of Caesarea • Aëtius • Demophilus of Constantinople • Eudoxius of Antioch • Eunomius of Cyzicus • Eusebius of Caesarea • Eusebius of Nicomedia • Eustathius of Sebaste • George of Laodicea • Ulfilas Other Arians • Asterius the Sophist • Auxentius of Milan • Auxentius of Durostorum • Constantius II • Wereka and Batwin • Fritigern • Alaric I • Artemius • Odoacer • Theodoric the Great Modern semi-Arians • Samuel Clarke • Isaac Newton • William Whiston Opponents • Peter of Alexandria • Achillas of Alexandria Arianism 2 • Alexander of Alexandria • Hosius of Cordoba • Athanasius of Alexandria • Paul I of Constantinople Christianity portal • v • t [1] • e Arianism is the theological teaching attributed to Arius (c. AD 250–336), a Christian presbyter in Alexandria, Egypt, concerning the relationship of God the Father to the Son of God, Jesus Christ. Arius asserted that the Son of God was a subordinate entity to God the Father. Deemed a heretic by the Ecumenical First Council of Nicaea of 325, Arius was later exonerated in 335 at the regional First Synod of Tyre,[2] and then, after his death, pronounced a heretic again at the Ecumenical First Council of Constantinople of 381. The Roman Emperors Constantius II (337–361) and Valens (364–378) were Arians or Semi-Arians. The Arian concept of Christ is that the Son of God did not always exist, but was created by—and is therefore distinct from—God the Father. -

The Polish Socinians: Contribution to Freedom of Conscience and the American Constitution

1 THE POLISH SOCINIANS: CONTRIBUTION TO FREEDOM OF CONSCIENCE AND THE AMERICAN CONSTITUTION Marian Hillar Published in Dialogue and Universalism, Vol. XIX, No 3-5, 2009, pp. 45-75 La société païenne a vécu sous le régime d'une substantielle tolérance religieuse jusqu'au moment où elle s'est trouvée en face du christianisme. Robert Joly1 Un Anglais comme homme libre, va au Ciel par le chemin qui lui plaît. Voltaire2 Abstract Socinians were members of the specific radical Reformation international religious group that was formed originally in Poland and in Transylvania in the XVIth century and went beyond the limited scope of the reform initiated by Luther or Calvin. At the roots of their religious doctrines was the Antitrinitarianism developed by Michael Servetus (1511-1553) and transplanted by Italian Humanists, as well as the social ideas borrowed initially from the Anabaptists and Moravian Brethren. They called themselves Christians or Brethren, hence Polish Brethren, also Minor Reformed Church. Their opponents labeled them after the old heresies as Sabellians, Samosatinians, Ebionites, Unitarians, and finally Arians. They were also known abroad as Socinians, after the Italian Faustus Socinus (1539-1604) (Fausto Sozzini, nephew of Lelio Sozzini) who at the end of the XVIth century became a prominent figure in the Raków Unitarian congregation for systematizing the doctrines of the Polish Brethren. Although the spirit of religious liberty was one of the elements of the Socinian doctrine, the persecution and coercion they met as a result of the Counter Reformation led them to formulate the most advanced ideas in the realm of human freedom and church-state relations. -

The Akademia Zamojska: Shaping a Renaissance University

Chapter 1 The Akademia Zamojska: Shaping a Renaissance University 1 Universities in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth In the course of the sixteenth century, in the territory initially under the juris- diction of Poland and, from 1569 on, of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, three centres of higher education were established that could boast the status of university. The first to be founded, in 1544, was the academy of Königsberg, known as the Albertina after the first Duke of Prussia, Albert of Hohenzollern. In actual fact, like other Polish gymnasia established in what was called Royal Prussia, the dominant cultural influence over this institution, was German, although the site purchased by the Duke on which it was erected was, at the time, a feud of Poland.1 It was indeed from Sigismund ii Augustus of Poland that the academy received the royal privilege in 1560, approval which – like the papal bull that was never ac- tually issued – was necessary for obtaining the status of university. However, in jurisdictional terms at least, the university was Polish for only one century, since from 1657 it came under direct Prussian control. It went on to become one of the most illustrious German institutions, attracting academics of international and enduring renown including the philosophers Immanuel Kant and Johann Gottlieb Fichte. The Albertina was conceived as an emanation of the University of Marburg and consequently the teaching body was strictly Protestant, headed by its first rector, the poet and professor of rhetoric Georg Sabinus (1508–1560), son-in-law of Philip Melanchthon. When it opened, the university numbered many Poles and Lithuanians among its students,2 and some of its most emi- nent masters were also Lithuanian, such as the professor of Greek and Hebrew 1 Karin Friedrich, The Other Prussia (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2000), 20–45, 72–74. -

CENTER for PHILOSOPHY, RELIGIOUS, and SOCINIAN STUDIES Marian Hillar M.D., Ph.D

CENTER FOR PHILOSOPHY, RELIGIOUS, AND SOCINIAN STUDIES Marian Hillar M.D., Ph.D. Professor of Philosophy and Religious Studies, Department of Biology and Biochemistry/Molecular Biology Website http://www.socinian.org College of Science and Technology Center for Socinians were members of the specific radical Reformation international religious group that was formed originally in Poland and in Transylvania in the Philosophy, XVIth century and went beyond the limited scope of the reform initiated by Religious Luther or Calvin. At the roots of their religious doctrines was the Antitrinitarianism developed by Michael Servetus (1511-1553) and transplanted and by Italian Humanists, as well as the social ideas borrowed initially from the Socinian Studies Anabaptists and Moravian Brethren. About the middle of the XVIth century a variety of Antitrinitarian sects emerged. They called themselves Christians or Brethren, hence Polish Brethren, also Minor Reformed Church. Their opponents labeled them after the old heresies as Sabellians, Samosatinians, Ebionites, Unitarians, and finally Arians. They were also known abroad as Socinians, after the Italian Faustus Socinus (1539-1604) (Fausto Sozzini, nephew of Lelio Sozzini) who at the end of the XVIth century became a prominent figure in the Raków Unitarian congregation for systematizing the doctrines of the Polish Brethren. Although the spirit of religious liberty was one of the elements of the Socinian doctrine, the persecution and coercion they met as a result of the Counter Reformation led them to formulate the most advanced ideas in the realm of human freedom and church-state relations. The intellectual ferment Socinian ideas produced in all of Europe determined the future philosophical trends and led directly to the development of Enlightenment. -

Isaac Newton, Socinianism And“Theonesupremegod”

Mulsow-Rohls. 11_Snobelen. Proef 1. 12-5-2005:15.16, page 241. ISAAC NEWTON, SOCINIANISM AND“THEONESUPREMEGOD” Stephen David Snobelen … we know that an idol is nothing in the world, and that there is none other God but one. For though there be that are called gods, whether in heaven or in earth, (as there be gods many, and lords many,) but to us there is but one God, the Father, of whom are all things, and we in him; and one Lord Jesus Christ, by whom are all things, and we by him. (1Corinthians 8:4–6) 1. Isaac Newton and Socinianism Isaac Newton was not a Socinian.1 That is to say, he was not a commu- nicant member of the Polish Brethren, nor did he explicitly embrace the Socinian Christology. What is more, Newton never expressly ac- knowledged any debt to Socinianism—characterised in his day as a heresy more dangerous than Arianism—and his only overt comment 1 The first version of this paper was written in 1997 as an MPhil assignment in History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Cambridge. I am grateful to Peter Lipton and my supervisor Simon Schaffer for their invaluable help at that time, along with David Money, who kindly refined my Latin translations. A later version of the paper was presented in November 2000 as a lecture in the Department of Early Hungarian Literature at the University of Szeged in Hungary. I benefited greatly from the knowledge and expertise of the scholars of the early modern Polish Brethren and Hungarian Unitarians associated with that department. -

Chapter Thirty the Ottoman Empire, Judaism, and Eastern Europe to 1648

Chapter Thirty The Ottoman Empire, Judaism, and Eastern Europe to 1648 In the late fifteenth and the sixteenth centuries, while the Portuguese and Spanish explored the oceans and exploited faraway lands, the eastern Mediterranean was dominated by the Ottomans. Mehmed II had in 1453 taken Constantinople and made it his capital, putting an end to the Byzantine empire. The subsequent Islamizing of Constantinople was abrupt and forceful. Immediately upon taking the city, Mehmed set about to refurbish and enlarge it. The population had evidently declined to fewer than two hundred thousand by the time of the conquest but a century later was approximately half a million, with Muslims constituting a slight majority. Mehmed and his successors offered tax immunity to Muslims, as an incentive for them to resettle in the city. Perhaps two fifths of the population was still Christian in the sixteenth century, and a tenth Jewish (thousands of Jewish families resettled in Constantinople after their expulsion from Spain in 1492). The large and impressive churches of Constantinople were taken over and made into mosques. Most dramatically, Mehmed laid claim to Haghia Sophia, the enormous cathedral that for nine hundred years had been the seat of the patriarch of Constantinople, and ordered its conversion into a mosque. It was reconfigured and rebuilt (it had been in a state of disrepair since an earthquake in 1344), and minarets were erected alongside it. The Orthodox patriarch was eventually placed in the far humbler Church of St. George, in the Phanari or “lighthouse” district of Constantinople. Elsewhere in the city Orthodox Christians were left with relatively small and shabby buildings.1 Expansion of the Ottoman empire: Selim I and Suleiman the Magnificent We have followed - in Chapter 26 - Ottoman military fortunes through the reigns of Mehmed II (1451-81) and Bayezid II (1481-1512). -

Unitarianism in Poland the Corn Poppy

The Garden of Unitarian*Universalism Unit 4: Poland Unitarianism in Poland The Corn Poppy The Garden of Unitarian*Universalism (12/2005) by Melinda Sayavedra and Marilyn Walker may not be published or used in any sort of profit-making manner. It is solely for the use of individuals and congregations to learn about international Unitarians and Universalists. Copies of the material may be made for educational use or for use in worship. The entire curriculum may be viewed and downloaded by going to http://www.icuu.net/resources/curriculum.html This project is funded in part by the Fund for Unitarian Universalism. Every effort has been made to properly acknowledge and reference sources and to trace owners of copyrighted material. We regret any omission and will, upon written notice, make the necessary correction(s) in subsequent editions. * The asterisk used in this curriculum in Unitarian*Universalism stands for “and/or” to include Unitarian, Universalist and Unitarian Universalist groups that are part of our international movement. The flower shape of the asterisk helps remind us that we are part of an ever-changing garden. Poland p. 2 Unitarianism in Poland: The Corn Poppy Table of Contents for Unit 4 Preparing for this Unit p. 3 Session 1: History and Context Preparing for Session 1 p. 4 Facilitating Session 1 p. 4 Handout: Blowing in the Wind: Seeds of Unitarianism in Poland p. 5-8 (with pre- and post-reading activities) Session 2: Beliefs and Practices Preparing for Session 2 p. 9 Facilitating Session 2 p. 9-10 Handout: A Truth-Seeking Tradition p.