The Pasha of Buda and the Edict of Torda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SERMON: "FRANCIS DAVID and the EDICT of TORDA" Francis

SERMON: "FRANCIS DAVID AND THE EDICT OF TORDA" Francis David (Ferencz David) was born at Klausenburg in Kolozsvar, the capital of Transylvania, in 1510. He was the son of a shoemaker and of a deeply religious mother descended from a noble family. He was first educated at a local Franciscan school, then at Gyulafehervar, a Catholic seminary. His high intellectual ability led him to the University of Wittenburg, where he completed his education 1545-1548 (then in his thirties). He developed the ability to debate fluently in Hungarian, German and Latin. His years of study fall in the exciting period of the Reformation. Although he must have been aware of and perhaps influenced by the debates of the time, his first position was that of rector of a Catholic school in Beszterce. He studied Luthers writings and became a Protestant. Lutheranism had spread rapidly in Transylvania during his absence and he joined the new movement on his return, becoming pastor of a Lutheran church in Peterfalva. He took part in theological debates, proving himself a gifted and powerful orator and a clear thinker. His fame spread, and he was elected as a Superintendent or Bishop of the Lutheran Church. The Calvinist or Reformed movement was at the same time spreading across Transylvania, and Francis David studied its teachings. Its main difference from Lutheranism lay in its symbolical interpretation of the Lords Supper. Gradually convinced, he resigned his Lutheran bishopric in 1559 and joined the Calvinists as an ordinary minister. Again, his intellectual ability and his gifts of oratory bore him to leadership and he was elected Bishop of the Reformed Church of Transylvania. -

The Crusade of Andrew II, King of Hungary, 1217-1218

IACOBVS REVIST A DE ESTUDIOS JACOBEOS Y MEDIEVALES C@/llOj. ~1)OI I 1 ' I'0 ' cerrcrzo I~n esrrrotos r~i corrnrro n I santiago I ' s a t'1 Cl fJ r1 n 13-14 SAHACiVN (LEON) - 2002 CENTRO DE ESTVDIOS DEL CAMINO DE SANTIACiO The Crusade of Andrew II, King of Hungary, 1217-1218 Laszlo VESZPREMY Instituto Historico Militar de Hungria Resumen: Las relaciones entre los cruzados y el Reino de Hungria en el siglo XIII son tratadas en la presente investigacion desde la perspectiva de los hungaros, Igualmente se analiza la politica del rey cruzado magiar Andres Il en et contexto de los Balcanes y del Imperio de Oriente. Este parece haber pretendido al propio trono bizantino, debido a su matrimonio con la hija del Emperador latino de Constantinopla. Ello fue uno de los moviles de la Quinta Cruzada que dirigio rey Andres con el beneplacito del Papado. El trabajo ofre- ce una vision de conjunto de esta Cruzada y del itinerario del rey Andres, quien volvio desengafiado a su Reino. Summary: The main subject matter of this research is an appro- ach to Hungary, during the reign of Andrew Il, and its participation in the Fifth Crusade. To achieve such a goal a well supported study of king Andrew's ambitions in the Balkan region as in the Bizantine Empire is depicted. His marriage with a daughter of the Latin Emperor of Constantinople seems to indicate the origin of his pre- tensions. It also explains the support of the Roman Catholic Church to this Crusade, as well as it offers a detailed description of king Andrew's itinerary in Holy Land. -

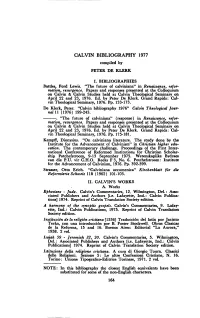

1977 Compiled by PETER DE KLERK

CALVIN BIBLIOGRAPHY 1977 compiled by PETER DE KLERK I. BIBLIOGRAPHIES Battles, Ford Lewis. "The future of calviniana" in Renaissance, refor mation, resurgence. Papers and responses presented at the Colloquium on Calvin & Calvin Studies held at Calvin Theological Seminary on April 22 and 23, 1976. Ed. by Peter De Klerk. Grand Rapids: Cal vin Theological Seminary, 1976. Pp. 133-173. De Klerk, Peter. "Calvin bibliography 1976" Calvin Theological Jour- nal U (1976) 199-243. -. "The future of calviniana" (response) in Renaissance, refor mation, resurgence. Papers and responses presented at the Colloquium on Calvin & Calvin Studies held at Calvin Theological Seminary on April 22 and 23, 1976. Ed. by Peter De Klerk. Grand Rapids: Cal vin Theological Seminary, 1976. Pp. 175-181. Kempff, Dionysius. "On calviniana literature. The study done by the Institute for the Advancement of Calvinism" in Christian higher edu cation. The contemporary challenge. Proceedings of the First Inter national Conference of Reformed Institutions for Christian Scholar ship Potchefstroom, 9-13 September 1975. Wetenskaplike Bydraes van die P.U. vir C.H.O. Reeks F 3, No. 6. Potchefstroom: Institute for the Advancement of Calvinism, 1976. Pp. 392-399. Strasser, Otto Erich. "Calviniana œcumenica" Kirchenblatt für die Reformierte Schweiz 118 (1962) 101-103. II. CALVIN'S WORKS A. Works Ephesians - Jude. Calvin's Commentaries, 12. Wilmington, Del.: Asso ciated Publishers and Authors [i.e. Lafayette, Ind.: Calvin Publica tions] 1974. Reprint of Calvin Translation Society edition. A harmony of the synoptic gospels. Calvin's Commentaries, 9. Lafay ette, Ind.: Calvin Publications, 1975. Reprint of Calvin Translation Society edition. Institución de la religion cristiana fi536] Traducción del latín por Jacinto Terán, con una introducción por Β. -

1. the Origin of the Cumans

Christianity among the Cumans Roger Finch 1. The Origin of the Cumans The question of where the Cumans originated has been the object of much study but a definitive answer to this cannot yet be given. The Cumans are known in Russian historical sources as Polovtsy and in Arabic sources generally as Kipchak Qipchak, although the Arabic author al-Marwazi writing about 1120 referred to them as Qûn, which corresponds to the Hungarian name for the Cumans, Kun. The Russian name for these people, Polovtsy < Slav. polovyi pale; pale yellow is supposedly a translation of the name Quman in Tur- kic, but there is no word in any Turkic dialect with this meaning; the only word in Turkic which at all approximates this meaning and has a similar form is OT qum sand, but this seems more an instance of folk etymology than a likely derivation. There is a word kom in Kirghiz, kaum in Tatar, meaning people, but these are from Ar. qaum fellow tribes- men; kinfolk; tribe, nation; people. The most probable reflexes of the original word in Tur- kic dialects are Uig., Sag. kun people, OT kun female slave and Sar. Uig. kun ~ kun slave; woman < *kümün ~ *qumun, cf. Mo. kümün, MMo. qu’un, Khal. xun man; person; people, and this is the most frequent meaning of ethnonyms in the majority of the worlds languages. The Kipchaks have been identified as the remainder of the Türküt or Türk Empire, which was located in what is the present-day Mongolian Republic, and which collapsed in 740. There are inscriptions engraved on stone monuments, located mainly in the basin of the Orkhon River, in what has been termed Turkic runic script; these inscriptions record events from the time the Türküt were in power and, in conjunction with information recorded in the Chinese annals of the time about them, we have a clearer idea of who these people were during the time their empire flourished than after its dissolution. -

General Historical Survey

General Historical Survey 1521-1525 tention to the Knights Hospitallers on Rhodes (which capitulated late During the later years of his reign Sultan Selīm I was engaged militar- in 1522 after a long siege). ily against the Safavid state in Iran and the Mamluk sultanate in Syria and Egypt, so Central Europe felt relatively safe. King Lajos II of Hun- gary was only ten years old when, in 1516, he succeeded to the throne 1526-1530 and was placed under guardianship. In 1506 he had already been be- Between 1523 and 1525 Süleyman and his Grand Vizier and favour- trothed to Maria, the sister of Emperor Ferdinand, by the Pact of Wie- ite, Ibrahim Pasha (d. 942/1536), were chiefly engaged in settling ner Neustadt, where a royal double marriage was arranged between the affairs of Egypt. His second campaign into Hungary, which was the Habsburg and Jagiello dynasties. The government of Hungary was launched in April 1526, led ultimately, after a slow and difficult march, entrusted to a State Council, a group of men who were interested only to a military encounter known as the first Battle of Mohács. It was in enriching themselves. In a word: the crown had been reduced to fought on 20 Zilkade 932/29 August 1526 on the plain of Mohács, west political insignificance; the country was in chaos, the treasury empty, of the Danube in southern Hungary, near the present-day intersection the army virtually non-existent and the system of defence utterly ne- of Hungary, Croatia and Serbia. Both Süleyman and Lajos II partic- glected. -

Arianism 1 Arianism

Arianism 1 Arianism "Arian" redirects here. For other uses, see Arian (disambiguation). Not to be confused with "Aryanism", which is a racial theory. Part of a series of articles on Arianism History and theology • Arius • Acacians • Anomoeanism • Arian controversy • First Council of Nicaea • Lucian of Antioch • Gothic Christianity Arian leaders • Acacius of Caesarea • Aëtius • Demophilus of Constantinople • Eudoxius of Antioch • Eunomius of Cyzicus • Eusebius of Caesarea • Eusebius of Nicomedia • Eustathius of Sebaste • George of Laodicea • Ulfilas Other Arians • Asterius the Sophist • Auxentius of Milan • Auxentius of Durostorum • Constantius II • Wereka and Batwin • Fritigern • Alaric I • Artemius • Odoacer • Theodoric the Great Modern semi-Arians • Samuel Clarke • Isaac Newton • William Whiston Opponents • Peter of Alexandria • Achillas of Alexandria Arianism 2 • Alexander of Alexandria • Hosius of Cordoba • Athanasius of Alexandria • Paul I of Constantinople Christianity portal • v • t [1] • e Arianism is the theological teaching attributed to Arius (c. AD 250–336), a Christian presbyter in Alexandria, Egypt, concerning the relationship of God the Father to the Son of God, Jesus Christ. Arius asserted that the Son of God was a subordinate entity to God the Father. Deemed a heretic by the Ecumenical First Council of Nicaea of 325, Arius was later exonerated in 335 at the regional First Synod of Tyre,[2] and then, after his death, pronounced a heretic again at the Ecumenical First Council of Constantinople of 381. The Roman Emperors Constantius II (337–361) and Valens (364–378) were Arians or Semi-Arians. The Arian concept of Christ is that the Son of God did not always exist, but was created by—and is therefore distinct from—God the Father. -

Making Maria Theresia 'King' of Hungary*

The Historical Journal, , (), pp. – © The Author(s), . Published by Cambridge University Press. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/./), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi:./SX MAKING MARIA THERESIA ‘ KING’ OF HUNGARY* BENEDEK M. VARGA Trinity Hall, Cambridge ABSTRACT. This article examines the succession of Maria Theresia as ‘king’ of Hungary in , by questioning the notion of the ‘king’s two bodies’, an interpretation that has dominated the scholar- ship. It argues that Maria Theresia’s coming to the throne challenged both conceptions of gender and the understanding of kingship in eighteenth-century Hungary. The female body of the new ruler caused anx- ieties which were mitigated by the revival of the medieval rex femineus tradition as well as ancient legal procedures aiming to stress the integrity of royal power when it was granted to a woman. When the Holy Roman Emperor, king of Hungary and Bohemia, Charles VI unexpectedly died in October , his oldest daughter and successor, the twenty-three-year-old Maria Theresia, had to shoulder the burdens of the Habsburg empire and face the ensuing War of Austrian Succession (–), the most severe crisis of the dynasty’s early modern history. The treasury was almost empty, the armies were exhausted, and the dynasty’s debt was high. Amidst these difficulties, it was essential for the young queen to emphasize the legitimacy of her power and secure the support of her lands, among them Hungary. -

Chapter Thirty the Ottoman Empire, Judaism, and Eastern Europe to 1648

Chapter Thirty The Ottoman Empire, Judaism, and Eastern Europe to 1648 In the late fifteenth and the sixteenth centuries, while the Portuguese and Spanish explored the oceans and exploited faraway lands, the eastern Mediterranean was dominated by the Ottomans. Mehmed II had in 1453 taken Constantinople and made it his capital, putting an end to the Byzantine empire. The subsequent Islamizing of Constantinople was abrupt and forceful. Immediately upon taking the city, Mehmed set about to refurbish and enlarge it. The population had evidently declined to fewer than two hundred thousand by the time of the conquest but a century later was approximately half a million, with Muslims constituting a slight majority. Mehmed and his successors offered tax immunity to Muslims, as an incentive for them to resettle in the city. Perhaps two fifths of the population was still Christian in the sixteenth century, and a tenth Jewish (thousands of Jewish families resettled in Constantinople after their expulsion from Spain in 1492). The large and impressive churches of Constantinople were taken over and made into mosques. Most dramatically, Mehmed laid claim to Haghia Sophia, the enormous cathedral that for nine hundred years had been the seat of the patriarch of Constantinople, and ordered its conversion into a mosque. It was reconfigured and rebuilt (it had been in a state of disrepair since an earthquake in 1344), and minarets were erected alongside it. The Orthodox patriarch was eventually placed in the far humbler Church of St. George, in the Phanari or “lighthouse” district of Constantinople. Elsewhere in the city Orthodox Christians were left with relatively small and shabby buildings.1 Expansion of the Ottoman empire: Selim I and Suleiman the Magnificent We have followed - in Chapter 26 - Ottoman military fortunes through the reigns of Mehmed II (1451-81) and Bayezid II (1481-1512). -

King St Ladislas, Chronicles, Legends and Miracles

Saeculum Christianum t. XXV (2018), s. 140-163 LÁSZLó VESZPRÉMY Budapest KING ST LADISLAS, CHRONICLES, LEGENDS AND mIRACLES The pillars of Hungarian state authority had crystallized at the end of the twelfth century, namely, the cult of the Hungarian saint kings (Stephen, Ladislas and Prince Emeric), especially that of the apostolic king Stephen who organized the Church and state. His cult, traditions, and relics played a crucial role in the development of the Hungarian coronation ritual and rules. The cult of the three kings was canonized on the pattern of the veneration of the three magi in Cologne from the thirteenth century, and it was their legends that came to be included in the Hungarian appendix of the Legenda Aurea1. A spectacular stage in this process was the foundation of the Hungarian chapel by Louis I of Anjou in Aachen in 1367, while relics of the Hungarian royal saints were distributed to the major shrines of pilgrimage in Europe (Rome, Cologne, Bari, etc.). Together with the surviving treasures, they were supplied with liturgical books which acquainted the non-Hungarians with Hungarian history in the special and local interpretation. In Hungary, the national and political implications of the legends of kings contributed to the representation of royal authority and national pride. Various information on King Ladislas (reigned 1077–1095) is available in the chronicles, legends, liturgical lections and prayers2. In some cases, the same motifs occur in all three types of sources. For instance, as to the etymology of the saint’s name, the sources cite a rare Greek rhetorical concept (per peragogen), which was first incorporated in the Chronicle, as the context reveals, and later transferred into the Legend and the liturgical lections. -

Francis-David.Faith-And-Freedom-2.7

Francis David: Faith and Freedom By Rev. Steven A. Protzman February 7th, 2016 © February, 2016 First Reading: The Edict of Torda1 Second Reading: dive for dreams by ee cummings2 Sermon Unitarianism has existed in Romania for more than 350 years. Among its heroes is Francis David, court preacher for the only Unitarian king in history, John Sigismund. As we honor our Partner Church this weekend with the Festival of the First Bread and begin our month of Unitarian Universalist history, we will learn about the legacy of David and Unitarianism in Transylvania, which includes some of our fundamental UU values: freedom, reason and tolerance. Part I Today as begin our month of UU history, we celebrate the Festival of the First Bread and our relationship with a small Unitarian village in Romania, Janosfalva. Today we will tell a story about the beginnings of Unitarianism almost 450 years ago in Eastern Europe and Francis David, one of our Unitarian heroes. Of the many remarkable parts of this story, perhaps the most amazing part is that a tiny kingdom on the eastern edge of Europe, Transylvania, had freedom of religion in an age where, as UU minister Frank Schulman said, "“the Inquisition was crushing religious freedom, John Calvin and his cohorts burned heretics like Michael Servetus at the stake for daring to question doctrine, when Luther wrote, “Let heads roll in the streets,” and when the massacre of St. Bartholomew killed 30,000 Protestants in France".3 It was during this tumultuous time when the Reformation and the Radical Reformation were underway and the first information age, created by the invention of the printing press, was changing the world radically and rapidly that Francis David was born in 1510 in Kolosvar, Transylvania, the son of a shoemaker. -

Mathias Rex of Hungary, Stephen the Great of Moldavia, and Vlad the Impaler of Walachia – History and Legend

Nicolae Constantinescu Mathias Rex of Hungary, Stephen the Great of Moldavia, and Vlad the Impaler of Walachia – History and Legend The three feudal rulers mentioned in the title of my paper reigned at approximately the same time, had close relationships, be these friendly or not, confronted the same enemy (chiefly the Ottoman Empire, as they ruled immediately after the fall of Constantinople in 1453), and faced the same dangers. All three entered history either as valiant defenders of their countries’ freedom, or as merciless punishers of their enemies. Probably the most famous, in this last respect, was Vlad III the Impaler, also known as (Count) Dracula, although his contemporaries were no less cruel or sanguinary. A recent study on Stephen the Great, who, in official history, is regarded as a symbol of the Moldavians’ (Romanians’) struggle for freedom and independence, and who was later even canonised, depicts the feudal ruler as a “Dracula the Westerners missed”. All three are doubly reflected in official history and in popular (folk) tradition, mainly in folk-legends and historical anecdotes, but also in folk-ballads and songs. Remembering them now offers an opportunity to revisit some old topics in folkloric studies, such as the relationship between historical truth and fictive truth, or the treatment of a historical character in various genres of folklore. In many cases, the historical facts have been coined according to the mythical logic that leads to a general model, multiplied in time and space according to the vision of the local creators and to their position regarding the historical personages about whom they narrate. -

Syllabus: Unitarianism in Transylvania Course ID: HS 4005 Instructor: Rev

Syllabus: Unitarianism in Transylvania Course ID: HS 4005 Instructor: Rev. Sándor Kovács PhD Associate Professor Protestant Theological Institute – Cluj/Kolozsvár [email protected] Course description Welcome to the Unitarianism in Transylvania course. This course will examine the history of the Unitarians in Transylvania and Central Eastern Europe from the development of the antitrinitarian movement to the last quarter of the 20th Century. The lecture-discussion course focuses on the ecclesiastical and political changes regarding Transylvanian Unitarianism. We will explore the history of Transylvania from the present days back to the previous centuries. Covering four centuries of history the participants will have the possibility to understand the religious and ethnical pluralism of the “land beyond the forests,” and the uniqueness of Unitarianism in Europe. Learning outcomes There are three purposes of this course: 1. to introduce the rich history of Transylvanian Unitarianism; 2. to show how “Transylvania” can challenge the way of thinking about religious leadership; 3. to deepen the relationship with Unitarian Universalists over the seas. Schedule Unit 1 (February 11) – Do we need to think alike? - The sentence is attributed to Francis David, what is behind it? - What do you know about Transylvania? If you have been there please bring items which connect you to Transylvania. - We are going to locate Transylvania on a map - The Unitarians living in Transylvania: numbers, statistics, maps - Parishes and districts. Congregational polity. Church governing policies - The Unitarian symbol – ways of interpretation, origin - Liturgy - Ministerial training Reading: No reading is required for the first meeting. Unit 2 (February 25)– Trauma or dilemma: the communist dictatorship - Cohabitate or collaborate for your survival? - What does “resistance” look like in a communist country - The risks of ministry - Communist strategies of repression - A Unitarian martyr mirror - Facing the past, problems of reconciliation Reading: Judit Gellérd: Prisoner of Liberté.