The Edict of Torda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review Copy. © 2021 Indiana University Press. All Rights Reserved. Do Not Share. STUDIES in HUNGARIAN HISTORY László Borhi, Editor

HUNGARY BETWEEN TWO EMPIRES 1526–1711 Review Copy. © 2021 Indiana University Press. All rights reserved. Do not share. STUDIES IN HUNGARIAN HISTORY László Borhi, editor Top Left: Ferdinand I of Habsburg, Hungarian- Bohemian king (1526–1564), Holy Roman emperor (1558–1564). Unknown painter, after Jan Cornelis Vermeyen, circa 1530 (Hungarian National Museum, Budapest). Top Right: Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent (1520–1566). Unknown painter, after Titian, sixteenth century (Hungarian National Museum, Budapest). Review Copy. © 2021 Indiana University Press. All rights reserved. Do not share. Left: The Habsburg siege of Buda, 1541. Woodcut by Erhardt Schön, 1541 (Hungarian National Museum, Budapest). STUDIES IN HUNGARIAN HISTORY László Borhi, editor Review Copy. © 2021 Indiana University Press. All rights reserved. Do not share. Review Copy. © 2021 Indiana University Press. All rights reserved. Do not share. HUNGARY BETWEEN TWO EMPIR ES 1526–1711 Géza Pálffy Translated by David Robert Evans Indiana University Press Review Copy. © 2021 Indiana University Press. All rights reserved. Do not share. This book is a publication of Indiana University Press Office of Scholarly Publishing Herman B Wells Library 350 1320 East 10th Street Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA iupress . org This book was produced under the auspices of the Research Center for the Humanities of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences and with the support of the National Bank of Hungary. © 2021 by Géza Pálffy All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. -

SERMON: "FRANCIS DAVID and the EDICT of TORDA" Francis

SERMON: "FRANCIS DAVID AND THE EDICT OF TORDA" Francis David (Ferencz David) was born at Klausenburg in Kolozsvar, the capital of Transylvania, in 1510. He was the son of a shoemaker and of a deeply religious mother descended from a noble family. He was first educated at a local Franciscan school, then at Gyulafehervar, a Catholic seminary. His high intellectual ability led him to the University of Wittenburg, where he completed his education 1545-1548 (then in his thirties). He developed the ability to debate fluently in Hungarian, German and Latin. His years of study fall in the exciting period of the Reformation. Although he must have been aware of and perhaps influenced by the debates of the time, his first position was that of rector of a Catholic school in Beszterce. He studied Luthers writings and became a Protestant. Lutheranism had spread rapidly in Transylvania during his absence and he joined the new movement on his return, becoming pastor of a Lutheran church in Peterfalva. He took part in theological debates, proving himself a gifted and powerful orator and a clear thinker. His fame spread, and he was elected as a Superintendent or Bishop of the Lutheran Church. The Calvinist or Reformed movement was at the same time spreading across Transylvania, and Francis David studied its teachings. Its main difference from Lutheranism lay in its symbolical interpretation of the Lords Supper. Gradually convinced, he resigned his Lutheran bishopric in 1559 and joined the Calvinists as an ordinary minister. Again, his intellectual ability and his gifts of oratory bore him to leadership and he was elected Bishop of the Reformed Church of Transylvania. -

The Crusade of Andrew II, King of Hungary, 1217-1218

IACOBVS REVIST A DE ESTUDIOS JACOBEOS Y MEDIEVALES C@/llOj. ~1)OI I 1 ' I'0 ' cerrcrzo I~n esrrrotos r~i corrnrro n I santiago I ' s a t'1 Cl fJ r1 n 13-14 SAHACiVN (LEON) - 2002 CENTRO DE ESTVDIOS DEL CAMINO DE SANTIACiO The Crusade of Andrew II, King of Hungary, 1217-1218 Laszlo VESZPREMY Instituto Historico Militar de Hungria Resumen: Las relaciones entre los cruzados y el Reino de Hungria en el siglo XIII son tratadas en la presente investigacion desde la perspectiva de los hungaros, Igualmente se analiza la politica del rey cruzado magiar Andres Il en et contexto de los Balcanes y del Imperio de Oriente. Este parece haber pretendido al propio trono bizantino, debido a su matrimonio con la hija del Emperador latino de Constantinopla. Ello fue uno de los moviles de la Quinta Cruzada que dirigio rey Andres con el beneplacito del Papado. El trabajo ofre- ce una vision de conjunto de esta Cruzada y del itinerario del rey Andres, quien volvio desengafiado a su Reino. Summary: The main subject matter of this research is an appro- ach to Hungary, during the reign of Andrew Il, and its participation in the Fifth Crusade. To achieve such a goal a well supported study of king Andrew's ambitions in the Balkan region as in the Bizantine Empire is depicted. His marriage with a daughter of the Latin Emperor of Constantinople seems to indicate the origin of his pre- tensions. It also explains the support of the Roman Catholic Church to this Crusade, as well as it offers a detailed description of king Andrew's itinerary in Holy Land. -

![List 3-2016 Accademia Della Crusca – Aldine Device 1) [BARDI, Giovanni (1534-1612)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5354/list-3-2016-accademia-della-crusca-aldine-device-1-bardi-giovanni-1534-1612-465354.webp)

List 3-2016 Accademia Della Crusca – Aldine Device 1) [BARDI, Giovanni (1534-1612)]

LIST 3-2016 ACCADEMIA DELLA CRUSCA – ALDINE DEVICE 1) [BARDI, Giovanni (1534-1612)]. Ristretto delle grandeze di Roma al tempo della Repub. e de gl’Imperadori. Tratto con breve e distinto modo dal Lipsio e altri autori antichi. Dell’Incruscato Academico della Crusca. Trattato utile e dilettevole a tutti li studiosi delle cose antiche de’ Romani. Posto in luce per Gio. Agnolo Ruffinelli. Roma, Bartolomeo Bonfadino [for Giovanni Angelo Ruffinelli], 1600. 8vo (155x98 mm); later cardboards; (16), 124, (2) pp. Lacking the last blank leaf. On the front pastedown and flyleaf engraved bookplates of Francesco Ricciardi de Vernaccia, Baron Landau, and G. Lizzani. On the title-page stamp of the Galletti Library, manuscript ownership’s in- scription (“Fran.co Casti”) at the bottom and manuscript initials “CR” on top. Ruffinelli’s device on the title-page. Some foxing and browning, but a good copy. FIRST AND ONLY EDITION of this guide of ancient Rome, mainly based on Iustus Lispius. The book was edited by Giovanni Angelo Ruffinelli and by him dedicated to Agostino Pallavicino. Ruff- inelli, who commissioned his editions to the main Roman typographers of the time, used as device the Aldine anchor and dolphin without the motto (cf. Il libro italiano del Cinquec- ento: produzione e commercio. Catalogo della mostra Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, Roma 20 ottobre - 16 dicembre 1989, Rome, 1989, p. 119). Giovanni Maria Bardi, Count of Vernio, here dis- guised under the name of ‘Incruscato’, as he was called in the Accademia della Crusca, was born into a noble and rich family. He undertook the military career, participating to the war of Siena (1553-54), the defense of Malta against the Turks (1565) and the expedition against the Turks in Hun- gary (1594). -

Myth and Reality. Changing Awareness of Transylvanian Identity

Sándor Vogel Transylvania: Myth and Reality. Changing Awareness of Transylvanian Identity Introduction In the course of history Transylvania has represented a specific configuration in Eur ope. A unique role was reserved for it by its three ethnic communities (Hungarian, Romanian and Saxon), its three estates in politicallaw, or natio (nations), Hungarian, Szekler and Saxon existing until modern times, and its four established religions (recepta re/igio), namely Catholic, Lutheran, Calvinist and Unitarian, along with the Greek Orthodox religion of Romanians which was tolerated by Transylvania's political law. At the same time the Transylvanian region was situated at the point of contact or intersection oftwo cultures, the Western and the East European. A glance at the ethnic map - displaying an oveIWhelming majority of Hungarians and Saxon settlers in medieval times - clearly reveals that its evolution is in many respects associated with the rise ofthe medieval State of Hungary and resultant from the Hungarian king's con scious policies of state organization and settlement. lts historical development, social order, system of state organization and culture have always made it a part of Europe in all these dimensions. During the centuries ofthe Middle Ages and early modern times the above-mention ed three ethnic communities provided the estate-based framework for the region's spe cial state organization. The latter served in turn as an integument for the later develop ment of nationhood for the Hungarian and Saxon communities, and as a model for the Romanian community. During the 16th and 17th centuries, the period of the Ottoman State's expansion, the Transylvanian region achieved the status of an independent state in what was referred to in contemporary Hungarian documents as the 'shadow ofthe Turkish Power', thereby becoming the repository ofthe idea of a Hungarian State, the ultimate resource of Hungarian culture and the nerve center of its development. -

Biblioteca.Txt 50 De Ani De La Apariția Operei Lui V.I

Biblioteca.txt 50 De Ani De La Apariția Operei Lui V.I. Lenin „Materialism Și Empiriocriticism”. Edited by C.I Gulian. București: Academiei RPR, 1960. 150 De Ani De Lectură Publică. Biblioteca... Edited by Silviu Borș. Sibiu: Armanis, 2011. 1948: Marea Dramă a României. Edited by Ioan Păuc Otiman. București: Academia Română, 2013. Abbrüche Und Aufbrüche. Die Rumäniendeutschen ... Sibiu: Honterus, 2014. Academia Artelor Tradiționale Din România. Edited by Corneliu Bucur. Sibiu: Astra Museum, 2008. Academia Română 1866-2016. Edited by Ionel-Valentin Vlad. București: Academia Română, 2016. Academia Română Și Casa Regală a României. București: Academia Română, 2013. Academia Română. Filiala Cluj-Napoca. Cercetarea ... Cluj-Napoca: Mega, 2016. Activitatea Științifică a Institutului De Istorie „G. Barițiu”. Edited by Nicolae Edroiu. București: Enciclopedică, 2011. Acțiunea „Recuperarea”. Securitatea Și Emigrarea ... București: Ed. Enciclopedică, 2011. Alltag Und Materielle Kultur Im Mittelalaterichen Ungarn. Edited by András Kubiny. Krems: Gesellschaft zur Erforschung der materiellen Kultur des Mittelalters, 1991. Am Kreuzweg Der Geschichte: Mühlbach Im Unterwald. Siebenbürgen. Edited by Gerhard M. Wagner. Moosburg a.d. Isar: HOG Mühlbach, 2014. The Ambiguous Nation Case Studies From... München: Oldenbourg, 2013. Amintirile Colonelului Lăcusteanu ... București: Polirom, 2015. Analele Academiei Rsr. Seria a Iv-A. București, 1982. Ancient Linear Fortifications on the Lower Danube ... Edited by Valeriu Sîrbu. Cluj-Napoca: Mega, 2015. Anfänge Des Städtewesens an Schelde, Maas Und Rhein Bis Zum Jahre 1000. Edited by Adriaan Verhulst. Köln, Wien: Böhlau, 1996. Antidoron. Centenarul Acad. Emil Condurachi (1912-2012). Edited Page 1 Biblioteca.txt by Zoe Petre. București: Academia Română, 2012. Antologie De Filosofie Românească. Edited by Mircea Mâciu. 3 vols. -

Monastic Landscapes of Medieval Transylvania (Between the Eleventh and Sixteenth Centuries)

DOI: 10.14754/CEU.2020.02 Doctoral Dissertation ON THE BORDER: MONASTIC LANDSCAPES OF MEDIEVAL TRANSYLVANIA (BETWEEN THE ELEVENTH AND SIXTEENTH CENTURIES) By: Ünige Bencze Supervisor(s): József Laszlovszky Katalin Szende Submitted to the Medieval Studies Department, and the Doctoral School of History Central European University, Budapest of in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Medieval Studies, and CEU eTD Collection for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Budapest, Hungary 2020 DOI: 10.14754/CEU.2020.02 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My interest for the subject of monastic landscapes arose when studying for my master’s degree at the department of Medieval Studies at CEU. Back then I was interested in material culture, focusing on late medieval tableware and import pottery in Transylvania. Arriving to CEU and having the opportunity to work with József Laszlovszky opened up new research possibilities and my interest in the field of landscape archaeology. First of all, I am thankful for the constant advice and support of my supervisors, Professors József Laszlovszky and Katalin Szende whose patience and constructive comments helped enormously in my research. I would like to acknowledge the support of my friends and colleagues at the CEU Medieval Studies Department with whom I could always discuss issues of monasticism or landscape archaeology László Ferenczi, Zsuzsa Pető, Kyra Lyublyanovics, and Karen Stark. I thank the director of the Mureş County Museum, Zoltán Soós for his understanding and support while writing the dissertation as well as my colleagues Zalán Györfi, Keve László, and Szilamér Pánczél for providing help when I needed it. -

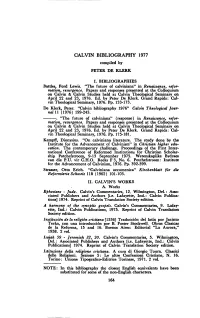

1977 Compiled by PETER DE KLERK

CALVIN BIBLIOGRAPHY 1977 compiled by PETER DE KLERK I. BIBLIOGRAPHIES Battles, Ford Lewis. "The future of calviniana" in Renaissance, refor mation, resurgence. Papers and responses presented at the Colloquium on Calvin & Calvin Studies held at Calvin Theological Seminary on April 22 and 23, 1976. Ed. by Peter De Klerk. Grand Rapids: Cal vin Theological Seminary, 1976. Pp. 133-173. De Klerk, Peter. "Calvin bibliography 1976" Calvin Theological Jour- nal U (1976) 199-243. -. "The future of calviniana" (response) in Renaissance, refor mation, resurgence. Papers and responses presented at the Colloquium on Calvin & Calvin Studies held at Calvin Theological Seminary on April 22 and 23, 1976. Ed. by Peter De Klerk. Grand Rapids: Cal vin Theological Seminary, 1976. Pp. 175-181. Kempff, Dionysius. "On calviniana literature. The study done by the Institute for the Advancement of Calvinism" in Christian higher edu cation. The contemporary challenge. Proceedings of the First Inter national Conference of Reformed Institutions for Christian Scholar ship Potchefstroom, 9-13 September 1975. Wetenskaplike Bydraes van die P.U. vir C.H.O. Reeks F 3, No. 6. Potchefstroom: Institute for the Advancement of Calvinism, 1976. Pp. 392-399. Strasser, Otto Erich. "Calviniana œcumenica" Kirchenblatt für die Reformierte Schweiz 118 (1962) 101-103. II. CALVIN'S WORKS A. Works Ephesians - Jude. Calvin's Commentaries, 12. Wilmington, Del.: Asso ciated Publishers and Authors [i.e. Lafayette, Ind.: Calvin Publica tions] 1974. Reprint of Calvin Translation Society edition. A harmony of the synoptic gospels. Calvin's Commentaries, 9. Lafay ette, Ind.: Calvin Publications, 1975. Reprint of Calvin Translation Society edition. Institución de la religion cristiana fi536] Traducción del latín por Jacinto Terán, con una introducción por Β. -

1. the Origin of the Cumans

Christianity among the Cumans Roger Finch 1. The Origin of the Cumans The question of where the Cumans originated has been the object of much study but a definitive answer to this cannot yet be given. The Cumans are known in Russian historical sources as Polovtsy and in Arabic sources generally as Kipchak Qipchak, although the Arabic author al-Marwazi writing about 1120 referred to them as Qûn, which corresponds to the Hungarian name for the Cumans, Kun. The Russian name for these people, Polovtsy < Slav. polovyi pale; pale yellow is supposedly a translation of the name Quman in Tur- kic, but there is no word in any Turkic dialect with this meaning; the only word in Turkic which at all approximates this meaning and has a similar form is OT qum sand, but this seems more an instance of folk etymology than a likely derivation. There is a word kom in Kirghiz, kaum in Tatar, meaning people, but these are from Ar. qaum fellow tribes- men; kinfolk; tribe, nation; people. The most probable reflexes of the original word in Tur- kic dialects are Uig., Sag. kun people, OT kun female slave and Sar. Uig. kun ~ kun slave; woman < *kümün ~ *qumun, cf. Mo. kümün, MMo. qu’un, Khal. xun man; person; people, and this is the most frequent meaning of ethnonyms in the majority of the worlds languages. The Kipchaks have been identified as the remainder of the Türküt or Türk Empire, which was located in what is the present-day Mongolian Republic, and which collapsed in 740. There are inscriptions engraved on stone monuments, located mainly in the basin of the Orkhon River, in what has been termed Turkic runic script; these inscriptions record events from the time the Türküt were in power and, in conjunction with information recorded in the Chinese annals of the time about them, we have a clearer idea of who these people were during the time their empire flourished than after its dissolution. -

General Historical Survey

General Historical Survey 1521-1525 tention to the Knights Hospitallers on Rhodes (which capitulated late During the later years of his reign Sultan Selīm I was engaged militar- in 1522 after a long siege). ily against the Safavid state in Iran and the Mamluk sultanate in Syria and Egypt, so Central Europe felt relatively safe. King Lajos II of Hun- gary was only ten years old when, in 1516, he succeeded to the throne 1526-1530 and was placed under guardianship. In 1506 he had already been be- Between 1523 and 1525 Süleyman and his Grand Vizier and favour- trothed to Maria, the sister of Emperor Ferdinand, by the Pact of Wie- ite, Ibrahim Pasha (d. 942/1536), were chiefly engaged in settling ner Neustadt, where a royal double marriage was arranged between the affairs of Egypt. His second campaign into Hungary, which was the Habsburg and Jagiello dynasties. The government of Hungary was launched in April 1526, led ultimately, after a slow and difficult march, entrusted to a State Council, a group of men who were interested only to a military encounter known as the first Battle of Mohács. It was in enriching themselves. In a word: the crown had been reduced to fought on 20 Zilkade 932/29 August 1526 on the plain of Mohács, west political insignificance; the country was in chaos, the treasury empty, of the Danube in southern Hungary, near the present-day intersection the army virtually non-existent and the system of defence utterly ne- of Hungary, Croatia and Serbia. Both Süleyman and Lajos II partic- glected. -

Edict of Torda 450Years

Sermon delivered at Glasgow Unitarian Church on 21 January 2018 by Rev John Clifford Edict of Torda, 450 years Well, if anyone had any doubt about what we are celebrating today before they left home for church, the excellent Chalice Lighting words from ICUU and the two readings from the Hungarian Unitarian Catechism should have dispelled all doubt. 450 years, almost to the day, since the Edict of Torda was promulgated by the King and Parliament of an Eastern European backwater that was effectively a buffer between Sultan Suleiman of the Ottoman Empire to the South and “Christian” civilisation to the West. The Edict itself was proclaimed following several public debates between different religious groups: The Roman Catholics, the Swiss Calvinists, the German Lutherans, and the followers of Pure Christianity who would come to be called Unitarians. These four groups had special status. The Eastern Orthodox, the Jews, and any other small groups like Anabaptists were not part of this journey towards toleration. We don't have the ceremony of Confirmation in our English speaking churches, although a few do have coming of age ceremonies. But I've been privileged to be at a Hungarian Unitarian Confirmation service. The teenagers, having been studying for some months and having completed a personal project, are gently interrogated by the minister about their self- understandings as Unitarians and their desire to become full members of the community. The youngsters were not expected to feed back sections of the Catechism verbatim, but it is the key normative document that organises their studies. The Unitarian Catechism from which we heard excerpts in the Reading dates the foundation of the Hungarian Unitarian Church from the Edict of Torda. -

Arianism 1 Arianism

Arianism 1 Arianism "Arian" redirects here. For other uses, see Arian (disambiguation). Not to be confused with "Aryanism", which is a racial theory. Part of a series of articles on Arianism History and theology • Arius • Acacians • Anomoeanism • Arian controversy • First Council of Nicaea • Lucian of Antioch • Gothic Christianity Arian leaders • Acacius of Caesarea • Aëtius • Demophilus of Constantinople • Eudoxius of Antioch • Eunomius of Cyzicus • Eusebius of Caesarea • Eusebius of Nicomedia • Eustathius of Sebaste • George of Laodicea • Ulfilas Other Arians • Asterius the Sophist • Auxentius of Milan • Auxentius of Durostorum • Constantius II • Wereka and Batwin • Fritigern • Alaric I • Artemius • Odoacer • Theodoric the Great Modern semi-Arians • Samuel Clarke • Isaac Newton • William Whiston Opponents • Peter of Alexandria • Achillas of Alexandria Arianism 2 • Alexander of Alexandria • Hosius of Cordoba • Athanasius of Alexandria • Paul I of Constantinople Christianity portal • v • t [1] • e Arianism is the theological teaching attributed to Arius (c. AD 250–336), a Christian presbyter in Alexandria, Egypt, concerning the relationship of God the Father to the Son of God, Jesus Christ. Arius asserted that the Son of God was a subordinate entity to God the Father. Deemed a heretic by the Ecumenical First Council of Nicaea of 325, Arius was later exonerated in 335 at the regional First Synod of Tyre,[2] and then, after his death, pronounced a heretic again at the Ecumenical First Council of Constantinople of 381. The Roman Emperors Constantius II (337–361) and Valens (364–378) were Arians or Semi-Arians. The Arian concept of Christ is that the Son of God did not always exist, but was created by—and is therefore distinct from—God the Father.