Cause They Don't Get to Come Here!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January 21, 2019 27 Nottingham City Schools Receive Award For

January 21, 2019 27 Nottingham City Schools receive award for commitment to music Nottingham City Schools were lauded for their commitment and collaboration with Nottingham’s music hub to provide their pupils with life-changing music opportunities. Nottingham Music Service (NMS), a registered charity that provides music programmes for young people in the city, introduced the ‘Music Hub Champion’ award to recognise schools that have gone the extra mile to promote inclusive music education and support their pupils to benefit from the many music making opportunities provided by NMS. These schools have extraordinary staff members that support, encourage and inspire their children to continue learning their instruments and participate in out-of- school groups and events. The awards were announced at NMS’s Christmas in the City event on Dec 12, 2018 at the Royal Concert Hall in front of an audience of 1,800+ people. Lord Mayor of Nottingham Councillor Liaqat Ali presented a certificate to representatives of the Champion schools. NMS Business, Operations & Strategy Manager Michael Aspinall says: “We wanted to publicly acknowledge those school that are going the extra mile to provide music educational opportunities for their pupils. We are proud of our work with local city schools and feel that it is important to recognise those schools that are helping students to engage with all aspects of the service.” The Music Hub Champion Schools for 2018 – 19 are: Bluecoat (Aspley) Academy Nottingham Academy Primary Bluecoat (Wollaton) Academy Nottingham -

Recruiting Talent in Gedling

Welcome to Recruiting Talent in Gedling Joelle Davies Service Manager Economic Growth and Regeneration Gedling Borough Council • Karen Bradford – Chief Executive, Gedling Borough Council • Dawn Edwards – President East Midlands Chamber • Lisa Vernon – D2N2 LEP BREAK • Workshop 1: Nottingham Jobs, BBO or Marketplace • Workshop 2: Chamber of Commerce, Nottinghamshire CC or Marketplace • Workshop 3: Princes Trust, Groundwork or Marketplace • Closing remarks NETWORKING LUNCH Karen Bradford Chief Executive Gedling Borough Council Dawn Edwards Challenge Consulting and President East Midlands Chamber Lisa Vernon Employment and Skills Coordinator D2N2 LEP The D2N2 Labour Market Lisa Vernon Skills & Enterprise Coordinator D2N2 Local Enterprise Partnership November 2019 Vision 2030 “By 2030, D2N2 will have a transformed high-value economy, prosperous, healthy and inclusive, and one of the most productive in Europe. The spark in the UK’s growth engine.” www.d2n2lep.org/sep Change • “The greatest danger in times of turbulence is not the turbulence—it is to act with yesterday’s logic.” —Peter Drucker • “All great changes are preceded by chaos.” — Deepak Chopra • “Change is the law of life and those who look only to the past or present are certain to miss the future.” —John F. Kennedy Global Trends • Automation will destroy and create jobs • Globalisation will require language skills • Population aging will require health skills • Urbanisation will require transport skills • Green economy will require new engineering skills • Health and education will grow • Food and retail will change • Skills for construction and agriculture will change futureskills.pearson.com 1. Demographic ‘squeeze’ “An ageing society with limited growth in working age population will make it harder to bridge the skills gap – we have to do more and better with what/who we have ” Population Jobs and Workforce Growth (to 2030) 2. -

Network News Spotlight on Sarah Gilkinson

Network News March 2013 Network News is a monthly newsletter produced during term time for teaching and support staff whose work involves DMU’s UK, undergraduate and postgraduate collaborative programmes. 4 2 5 2 3 3 11 42 3 4 3 5 5 7 7 52 32 In this edition: 1 Happy Easter 2 Confetti Industry Week 2013 3 £70m Centre for Central College Nottingham 4 Spotlight on Sarah Gilkinson Network News Contents Happy Easter 1 Confetti Industry Week 2013 2 £70m Centre for Central College Nottingham 3 Spotlight on Sarah 3 Gilkinson 4 Colleges share Principal and Chief Executive Educational Partnerships wish you all a Happy Easter. Please note that the university will be closed from: 5 Friday 29 March Professorial Lecture Series and will reopen: Wednesday 3 April. 1 56 1 Network News Confetti Industry Week 2013 England and working for Madonna. She was an inspiring Confetti Institute of Technologies has just celebrated its twelfth annual Industry Week. An event that just and motivating speaker and gave students a valuable gets bigger and better. For one week in February the insight into the mechanisms of film and television usual timetable stops and their 1000 Further drama. Education and Higher Education students attend a myriad of inspiring day time lectures, seminars and Music legends DJ Phantasy and Harry Shotta cooked up workshops and an exciting array of evening events. a storm with the students in our famed recording studio Electric Mayhem. “It truly was a pleasure to be part of For their students studying TV & Film, Music your industry week and it was great to meet so many Technology, Technical Events Production and Gaming different students who all have different ambitions and the industry experts’ insights into the ‘real world’ goals. -

Post-16 Options Booklet

Contents Page Page 1 – What Are The Options Available & How Do I Pay For It Page 2 – Sixth Form Colleges Page 3 – Local Sixth Form ‐ Contact Details Page 4 – Further Education Colleges Page 5 – Local Colleges ‐ Contact Details Page 6 – What Are T Levels? Page 7 – Apprenticeships & Traineeships Page 8 – Providers of Apprenticeships & Traineeships ‐ Contact Details Page 9 – Applying For Post 16 – How Does It Work? Page 10 – Frequently Asked Questions About Applying Page 11 – Entry Requirements Page 12 – Qualification Levels Guide Page 13 – How Do I Make My Final Decision About Post 16? Page 14 & 15 – Useful Websites and Where To Seek Further Support Since 2013, the Raising of the Participation Age law has stated that young people must be in some form of ‘education or training’ until they are 18. This can include: Full‐Time Study – this could be a qualification taken at a sixth form, college or training provider, totalling 540 hours of learning time per year, or around 18 hours per week. Apprenticeships – this involves working for an employer while studying for a qualification as part of your training. Usually, work makes up 80% of an apprenticeship and at least 20% (or one day a week) should be dedicated to studying. Traineeships – this is an option for students who would like to do an apprenticeship but may not have the experience, skills or qualifications to do so yet. Traineeships can last up to six months and involve a work placement, Maths and English qualifications and support with finding an apprenticeship. Part‐Time Study with Employment or Volunteering – this could be working in a full‐time job (classed as any work that takes place over more than two months and is over 20 hours per week) or volunteering (again, over 20 hours per week) while studying part‐ time at a college or training provider (totalling 280 hours of learning per year). -

EIB Board Minutes 20Th March 2019

Minutes of the Meeting of the Education Improvement Board of 20th March 2019. Present: Sir David Greenaway (DG) University of Nottingham John Dexter (JDx) Nottingham City Council (Education) John Dyson (JDy) Raleigh Trust Chris Hall (CH) University of Nottingham Sian Hampton (SH) Archway Trust Nick Lee (NL) (Alison Michalska) Nottingham City Council (Education) Matt Varley (MV) (Jane Moore) Nottingham Trent University Cllr Jon Collins (JC) Leader Nottingham City Council Liz Anderson (LA) Djanogly Learning Trust Tom Dick (TD) Nottingham College *Rav Kalsi (RK) Nottingham City Council (Executive Support) *Jonny Kirk (JK) Nottingham City Council (Admissions) *Lucy Juby (LJ) Nottingham City Council (Admissions) (*Invited guests) Apologies: Rebecca Meredith Transform Trust Cllr Neghat Khan Portfolio holder Nottingham City Council Kevin Fear Nottingham High School Matt Lawrence Teaching School Alliance LEAD Wayne Norrie Greenwood Dale Academies Trust Pat Fielding Nottingham Schools Trust Andy Burns Redhill Academy Trust Sir David thanked Cllr Jon Collins for his contribution to the Board before he steps down as leader of Nottingham City Council. 1) The minutes of the last meeting of 21st November were accepted as a correct record. • Sir David (DG) apologizes the minutes were delayed as had to be careful as Amanda Spielman attended and it’s a public document 2) Business Documents: • Budget - John Dexter (JDx) confirms that math’s support, Thistley Hough and science support is due to end this summer unless the board asks for them to continue. The EIB has contributed to numerous projects such as the Unlock Programme, Ambitious Literacy Campaign and Active Tutoring. The projects are commissioned via speaking to the relevant heads and getting a sense of what might help. -

Aoc Sport East Midlands Regional Tournament Results 2017

AoC Sport East Midlands Regional Tournament Results 2017 Badminton Women’s Singles Badminton Men’s Singles Pos Name College Pos Name College 1 Emma Hooper Lincoln College 1 Ryan Curtis Stamford College 2 Eve Dale Loughborough 2 Ethan Smith Bilborough College 3 Kate Garnham Lincoln College 3 Daniel Straw Bilborough College 4 Jaskirat Kanwal Wyggeston and QE 4 Tom Wyggeston and QE Cowperthwaite Women’s Basketball Men’s Basketball Pos College Pos College 1 Wyggeston 1 Loughborough 2 Bilborough 2 Gateway 3 Bilborough 4 Wyggeston and Queen Elizabeth 5 Nottingham College 6 Brooksby Melton 7 New College Stanford Cricket – Indoor24 Pos College 1 Derby College 2 Bilborough College 3 Nottingham College 4 Burton and South Derbyshire AoC Sport East Midlands Regional Tournament Results 2017 Cross Country – Women’s Regional Pos Name College 1 Eleanor Miller Bilborough College 2 Megan Hellam Nottingham College 3 Elizabeth Snodgrass New College Stamford 4 Leah Clark New College Stamford 5 Catherine Snodgrass New College Stamford 6 Shannon Beadsworth Nottingham College 7 Shannon Goton Burton and South Derby Cross Country – Men’s Regional Pos Name College 1 Milan Campion Bilborough College 2 Luke Ward Derby College 3 Tom Wood Derby College 4 Mohamed Nottingham College 5 Zac Treween New College Stamford 6 Zamal Nottingham College 7 Devids Ots Burton and South Derbyshire 8 Jojo Daji Burton and South Derbyshire 9 (1st res) Warren Pearson Burton and South Derbyshire 10 (2nd res) Ed Nawaz Burton and South Derbyshire 11(3rd res) George Derby College 12 Owen -

237 Colleges in England.Pdf (PDF,196.15

This is a list of the formal names of the Corporations which operate as colleges in England, as at 3 February 2021 Some Corporations might be referred to colloquially under an abbreviated form of the below College Type Region LEA Abingdon and Witney College GFEC SE Oxfordshire Activate Learning GFEC SE Oxfordshire / Bracknell Forest / Surrey Ada, National College for Digital Skills GFEC GL Aquinas College SFC NW Stockport Askham Bryan College AHC YH York Barking and Dagenham College GFEC GL Barking and Dagenham Barnet and Southgate College GFEC GL Barnet / Enfield Barnsley College GFEC YH Barnsley Barton Peveril College SFC SE Hampshire Basingstoke College of Technology GFEC SE Hampshire Bath College GFEC SW Bath and North East Somerset Berkshire College of Agriculture AHC SE Windsor and Maidenhead Bexhill College SFC SE East Sussex Birmingham Metropolitan College GFEC WM Birmingham Bishop Auckland College GFEC NE Durham Bishop Burton College AHC YH East Riding of Yorkshire Blackburn College GFEC NW Blackburn with Darwen Blackpool and The Fylde College GFEC NW Blackpool Blackpool Sixth Form College SFC NW Blackpool Bolton College FE NW Bolton Bolton Sixth Form College SFC NW Bolton Boston College GFEC EM Lincolnshire Bournemouth & Poole College GFEC SW Poole Bradford College GFEC YH Bradford Bridgwater and Taunton College GFEC SW Somerset Brighton, Hove and Sussex Sixth Form College SFC SE Brighton and Hove Brockenhurst College GFEC SE Hampshire Brooklands College GFEC SE Surrey Buckinghamshire College Group GFEC SE Buckinghamshire Burnley College GFEC NW Lancashire Burton and South Derbyshire College GFEC WM Staffordshire Bury College GFEC NW Bury Calderdale College GFEC YH Calderdale Cambridge Regional College GFEC E Cambridgeshire Capel Manor College AHC GL Enfield Capital City College Group (CCCG) GFEC GL Westminster / Islington / Haringey Cardinal Newman College SFC NW Lancashire Carmel College SFC NW St. -

Children with Disabilities And/Or Special Educational Needs A

Children with Disabilities and/or Special Educational Needs A Needs Assessment for Nottinghamshire September 2012 “I am very grateful for the respite and play services my son receives and would feel far less anxious if I could be assured that planners were assessing needs for the growing population……..coming through the system and that provision, recruitment and training of staff should be happening now to meet their needs once they reach adulthood.” Local parent Developed by the Nottinghamshire Joint Commissioning Group for Children with Disabilities and/or Special Educational Needs 1 2 Contributors Ann Berry Public Health, NHS Nottinghamshire County David Pearce Public Health, NHS Nottinghamshire County Denis McCarthy Nottinghamshire Futures Edwina Cosgrove Parent Partnership Fran Arnold Children’s Social Care, Nottinghamshire County Council Geoff Hamilton Policy & Planning, Nottinghamshire County Council Helen Crowder SEND Service, Nottinghamshire County Council Irene Kakoullis Health Partnerships, Nottinghamshire County Council Kirti Shah Policy & Planning, Nottinghamshire County Council Liz Marshall Early Years & Early Intervention, Nottinghamshire County Council Louise Benson Nottinghamshire Futures Michelle Crunkhorn Business & Administration, Nottinghamshire County Council Richard Fisher SEND Service, Nottinghamshire County Council Sally Moorcroft NAVO Sarah Everest Public Health, NHS Nottinghamshire County Scott Smith SEND Service, Nottinghamshire County Council Simon Bernacki Disability Nottinghamshire Sue Bold Data Management, -

Greater Lincolnshire Colleges and Universities (Emfec)

BTECs) in: Science and Mathematics, Social Sciences, to tomorrow’s workforce and find out how the college Literature and Languages, ICT, Business Administration, community can support the business world too. Finance and Law, Health, Public Services and Care, > The College already have successful business partnerships Leadership Skills, Engineering, Travel and Tourism, and are developing innovative programmes, including: Electronics, English for Speakers of Other Languages. work placements, employer linked commissions, > John Leggott works proactively with the region’s competitions or projects, Business mentors working with employers to help inspire students, promote organisations students, Stepping stones to Apprenticeships. University Technical Colleges University Technical Colleges (UTCs) are a new initiative in technical schooling for 14 to 19-year-old students. Learning is delivered in a very practical way, integrating National Curriculum requirements with technical and vocational elements. A UTC: and delivered by companies including Able UK, BAE Greater Lincolnshire contributes > Focuses on one or two technical specialisms. Systems, Centrica Storage, TATA Steel, SMart Wind and Clugstons, and based on leading research carried out at > Works with employers and a local university to develop the University of Hull. over £16 billion to the national and deliver their curriculum. > Provides essential academic education and relates this to Lincoln UTC the technical specialisms. economy and has real potential to > Lincoln UTC opened in September 2014 and specialises in Humber UTC Engineering and Science for 14–18 year olds. > The UTC aspires to become a regional hub for > Humber UTC (located in Scunthorpe) opens in September deliver sustainable growth. technological innovation and the new engineering 2015 and will specialise in Renewables & Engineering, for applications. -

List of Eligible Schools for Website 2019.Xlsx

England LEA/Establishment Code School/College Name Town 873/4603 Abbey College, Ramsey Ramsey 860/4500 Abbot Beyne School Burton‐on‐Trent 888/6905 Accrington Academy Accrington 202/4285 Acland Burghley School London 307/6081 Acorn House College Southall 931/8004 Activate Learning Oxford 307/4035 Acton High School London 309/8000 Ada National College for Digital Skills London 919/4029 Adeyfield School Hemel Hempstead 935/4043 Alde Valley School Leiston 888/4030 Alder Grange School Rossendale 830/4089 Aldercar High School Nottingham 891/4117 Alderman White School Nottingham 335/5405 Aldridge School ‐ A Science College Walsall 307/6905 Alec Reed Academy Northolt 823/6905 All Saints Academy Dunstable Dunstable 916/6905 All Saints' Academy, Cheltenham Cheltenham 301/4703 All Saints Catholic School and Technology College Dagenham 879/6905 All Saints Church of England Academy Plymouth 383/4040 Allerton Grange School Leeds 304/5405 Alperton Community School Wembley 341/4421 Alsop High School Technology & Applied Learning Specialist College Liverpool 358/4024 Altrincham College Altrincham 868/4506 Altwood CofE Secondary School Maidenhead 825/4095 Amersham School Amersham 380/4061 Appleton Academy Bradford 341/4796 Archbishop Beck Catholic Sports College Liverpool 330/4804 Archbishop Ilsley Catholic School Birmingham 810/6905 Archbishop Sentamu Academy Hull 306/4600 Archbishop Tenison's CofE High School Croydon 208/5403 Archbishop Tenison's School London 916/4032 Archway School Stroud 851/6905 Ark Charter Academy Southsea 304/4001 Ark Elvin Academy -

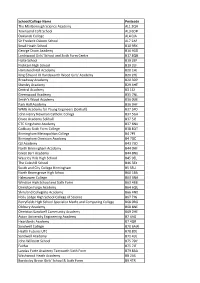

Global Recognition List August

Accept PTE Academic: pearsonpte.com/accept Africa Egypt • Global Academic Foundation - Hosting university of Hertfordshire • Misr University for Science & Technology Libya • International School Benghazi Nigeria • Stratford Academy Somalia • Admas University South Africa • University of Cape Town Uganda • College of Business & Development Studies Accept PTE Academic: pearsonpte.com/accept August 2021 Africa Technology & Technology • Abbey College Australia • Australian College of Sport & Australia • Abbott School of Business Fitness • Ability Education - Sydney • Australian College of Technology Australian Capital • Academies Australasia • Australian Department of • Academy of English Immigration and Border Protection Territory • Academy of Information • Australian Ideal College (AIC) • Australasian Osteopathic Technology • Australian Institute of Commerce Accreditation Council (AOAC) • Academy of Social Sciences and Language • Australian Capital Group (Capital • ACN - Australian Campus Network • Australian Institute of Music College) • Administrative Appeals Tribunal • Australian International College of • Australian National University • Advance English English (AICE) (ANU) • Alphacrucis College • Australian International High • Australian Nursing and Midwifery • Apex Institute of Education School Accreditation Council (ANMAC) • APM College of Business and • Australian Pacific College • Canberra Institute of Technology Communication • Australian Pilot Training Alliance • Canberra. Create your future - ACT • ARC - Accountants Resource -

2020 Aston Ready School and College List

School/College Name Postcode The Marlborough Science Academy AL1 2QA Townsend CofE School AL3 6DR Oaklands College AL4 0JA Sir Frederic Osborn School AL7 2AF Small Heath School B10 9RX George Dixon Academy B16 9GD Lordswood Girls' School and Sixth Form Centre B17 8QB Holte School B19 2EP Nishkam High School B19 2LF Hamstead Hall Academy B20 1HL King Edward VI Handsworth Wood Girls' Academy B20 2HL Broadway Academy B20 3DP Shenley Academy B29 4HE Central Academy B3 1SJ Greenwood Academy B35 7NL Smith's Wood Academy B36 0UE Park Hall Academy B36 9HF WMG Academy for Young Engineers (Solihull) B37 5FD John Henry Newman Catholic College B37 5GA Grace Academy Solihull B37 5JS CTC Kingshurst Academy B37 6NU Cadbury Sixth Form College B38 8QT Birmingham Metropolitan College B4 7PS Birmingham Ormiston Academy B4 7QD Q3 Academy B43 7SD North Birmingham Academy B44 0HF Great Barr Academy B44 8NU Waseley Hills High School B45 9EL The Coleshill School B46 3EX South and City College Birmingham B5 5SU North Bromsgrove High School B60 1BA Halesowen College B63 3NA Windsor High School and Sixth Form B63 4BB Ormiston Forge Academy B64 6QU Shireland Collegiate Academy B66 4ND Holly Lodge High School College of Science B67 7JG Perryfields High School Specialist Maths and Computing College B68 0RG Oldbury Academy B68 8NE Ormiston Sandwell Community Academy B69 2HE Aston University Engineering Academy B7 4AG Heartlands Academy B7 4QR Sandwell College B70 6AW Health Futures UTC B70 8DJ Sandwell Academy B71 4LG John Willmott School B75 7DY Fairfax B75 7JT Landau