Technical Guidance on Assessing Impacts to Air Quality in NEPA and Planning Documents January 2011 Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/ARD/NRR—2011/ 289

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quality Assurance Project Plan (Qapp)

FCEAP Criteria Air Pollutants QAPP September 2017 Page 1 of 109 Revision 0 QUALITY ASSURANCE PROJECT PLAN (QAPP) FOR AMBIENT AIR QUALITY MONITORING OF CRITERIA AIR POLLUTANTS 9/5/17 SUBMITTED BY THE FORSYTH COUNTY OFFICE OF ENVIRONMENTAL ASSISTANCE AND PROTECTION (FCEAP) FCEAP Criteria Air Pollutants QAPP September 2017 Page 2 of 109 Revision 0 Quality Assurance Project Plan Acronym Glossary A&MD- Analysis and Monitoring Division A&MPM- Analysis and Monitoring Program Manager AQI – Air Quality Index AQS - Air Quality System (EPA's Air database) CFR – Code of Federal Regulations DAS - Data Acquisition System DQA - Data Quality Assessment DQI - Data Quality Indicator DQO - Data Quality Objective EPA - Environmental Protection Agency FCEAP-Forsyth County Office of Environmental Assistance and Protection FTS - Flow Transfer Standard FEM – Federal Equivalent Method FRM – Federal Reference Method LAN – Local Area Network MQO – Measurement Quality Objective NAAQS - National Ambient Air Quality Standards NCDAQ - North Carolina Division of Air Quality NIST - National Institute of Science and Technology NPAP - National Performance Audit Program PEP – Performance Evaluation Program PQAO – Primary Quality Assurance Organization QA – Quality Assurance QA/QC - Quality Assurance/Quality Control QAPP - Quality Assurance Project Plan QC – Quality Control SD – Standard Deviation SLAMS - State and Local Air Monitoring Station SOP - Standard Operating Procedure SPM - Special Purpose Monitor TEOM - Tapered Elemental Oscillating Microbalance TSA - Technical -

Indicators in Practice: How Environmental Indicators Are Being Used in Policy and Management Contexts

8c\o[\J_\iY`e`e#8XifeI\lY\e#DXiZ8%C\mp#Xe[CXliXAf_ejfe )'(* Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 4 2. BACKGROUND .................................................................................................................................. 4 3. THE USE OF INDICATORS .................................................................................................................. 7 4. FACTORS AFFECTING THE ROLES AND INFLUENCE OF INDICATORS ................................................. 11 5. GOING FORWARD – FUTURE ACTION AND RESEARCH .................................................................... 15 REFERENCES ....................................................................................................................................... 17 ANNEX 1. CASE STUDIES ..................................................................................................................... 21 1. AFRICA CASE STUDY ...................................................................................................................... 21 Energy, Environment and Development Network for Africa .............................................................. 21 2. CAMBODIA CASE STUDY................................................................................................................. 22 The Tonle Sap Rural Water Supply and Sanitation Sector Project of Cambodia ............................... 22 3. DENMARK CASE STUDY -

Technical Assistance Document for the Reporting of Daily Air Quality – the Air Quality Index (AQI)

Technical Assistance Document for the Reporting of Daily Air Quality – the Air Quality Index (AQI) EPA 454/B-18-007 September 2018 Technical Assistance Document for the Reporting of Daily Air Quality – the Air Quality Index (AQI) U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Air Quality Planning and Standards Air Quality Assessment Division Research Triangle Park, NC CONTENTS I. REPORTING THE AQI II. CALCULATING THE AQI III. FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS IV. RESOURCES LIST OF TABLES Table 1. Names and colors for the six AQI categories Table 2. AQI color formulas Table 3. Pollutant-Specific Sensitive Groups Table 4. Cautionary Statements Table 5. Breakpoints for the AQI LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1. The AQI is reported in many formats Figure 2. Display of AQI forecast Figure 3. The NowCast Figure 4. Airnow.gov page showing the AQI at U.S. Embassies and Consulates Figure 5. The AQI on AirNow’s Fires: Current Conditions page Figure 6. The AirNow widget This guidance is designed to aid local agencies in reporting air quality using the Air Quality Index (AQI) as required in 40 CFR Part 58.50 and according to 40 CFR Appendix G to Part 58. I. REPORTING THE AQI Do I have to report the AQI? Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs) with a population of more than 350,000 are required to report the AQI daily to the general public. The population of an MSA for purposes of index reporting is based on the latest available U.S. census population. How often do I report the AQI? MSAs must report the AQI daily, which is defined as at least five days each week. -

THE AIR QUALITY INDEX FACT SHEET Using Air Quality Information to Protect Yourself from Ozone Air Pollution

Air Quality Index Fact Sheet www.lung.org 1-800-LUNG-USA 200 150 100 50 Schools AIR QUALITY INDEX and THE AIR QUALITY INDEX FACT SHEET Using Air Quality Information to Protect Yourself From Ozone Air Pollution The Air Quality Index, or AQI, is the standardized system that state and local air pollution control programs use to notify the public about levels of air pollution. Keeping track of the current air quality information can help you plan your activities during the ozone season so as to minimize your exposure to unhealthy levels of air pollution. This is especially important for people who are sensitive to air pollution, including young children, and people with asthma and other lung diseases. The American Lung Association also recommends that the elderly take precautions on high ozone and high particle pollution days. How Does the Air Quality Index Work? In most cities and suburbs, air pollution levels are measured daily and ranked on a scale of 0 for pristine air all the way up to 500 for air pollution levels that pose immediate danger to the public (fortunately, we do not have pollution levels that high in this country anymore). The AQI further breaks air pollution levels into five categories, each of which has a descriptor (name), color, and advisory statement. The AQI tracks levels of two pollutants: ozone (smog) and particle pollution. The purpose of the AQI is to help you understand what local air quality means to your health. To make it easier to understand, the AQI is divided into six categories. -

A Review on Air Quality Indexing System

Asian Journal of Atmospheric Environment Vol. 9-2, pp. 101-113, June 2015 Ozone Concentration in the Morning in InlandISSN(Online) Kanto Region 2287-1160 101 doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.5572/ajae.2015.9.2.101 ISSN(Print) 1976-6912 A Review on Air Quality Indexing System Kanchan, Amit Kumar Gorai1),* and Pramila Goyal2) Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Birla Institute of Technology, Mesra, Ranchi835215, India 1)Department of Mining Engineering, National Institute of Technology, Rourkela, Odisha769008, India 2)Centre for Atmospheric Sciences, Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi, Delhi110016, India *Corresponding author. Tel: +916612462938, Email: [email protected] Globally, many cities continuously assess air quality ABSTRACT using monitoring networks designed to measure and record air pollutant concentrations at several points Air quality index (AQI) or air pollution index (API) is deemed to represent exposure of the population to commonly used to report the level of severity of air these pollutants. Current research indicates that guide pollution to public. A number of methods were dev eloped in the past by various researchers/environ lines of recommended pollution values cannot be regar mental agencies for determination of AQI or API but ded as threshold values below which a zero adverse there is no universally accepted method exists, which response may be expected. Therefore, the simplistic is appropriate for all situations. Different method comparison of observed values against guidelines may uses different aggregation function in calculating mislead unless suitably quantified. In recent years, air AQI or API and also considers different types and quality information are provided by governments to the numbers of pollutants. -

Revised Air Quality Standards for Particle Pollution and Updates to the Air Quality Index (Aqi)

The National Ambient Air Quality Standards for Particle Pollution REVISED AIR QUALITY STANDARDS FOR PARTICLE POLLUTION AND UPDATES TO THE AIR QUALITY INDEX (AQI) On Dec. 14, 2012 the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) strengthened the nation’s air quality standards for fine particle pollution to improve public health protection by revising the 3 primary annual PM2.5 standard to 12 micrograms per cubic meter (µg/m ) and retaining the 24- hour fine particle standard of 35 µg/m3. Exposure to fine particle pollution can cause premature death and harmful cardiovascular effects such as heart attacks and strokes, and is linked to a variety of other significant health problems. Particle pollution also harms public welfare, including causing haze in cities and some of our nation’s most treasured national parks. EPA has issued a number of rules that will make significant strides toward reducing fine particle pollution (PM2.5). These rules will help the vast majority of U.S. counties meet the revised PM2.5 standard without taking additional action to reduce emissions. AIR QUALITY STANDARDS The Clean Air Act requires EPA to set two types of outdoor air quality standards: primary standards, to protect public health, and secondary standards, to protect the public against adverse environmental effects. The law requires that primary standards be “requisite to protect public health with an adequate margin of safety,” including the health of people most at risk from PM exposure. These include people with heart or lung disease, children, older adults and people of lower socioeconomic status. Secondary standards must be “requisite to protect the public welfare” from both known and anticipated adverse effects. -

World-Air-Quality-Report-2020-En.Pdf

2020 World Air Quality Report Region & City PM2.5 Ranking Contents About this report ................................................................................................ 3 Executive summary ............................................................................................. 4 Where does the data come from? ........................................................................... 5 Why PM2.5? Data presentation ................................................................................................ 6 COVID-19, air pollution and health .......................................................................... 7 Links between COVID-19 and PM2.5 Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on air quality Global overview ................................................................................................. 10 World country ranking World capital city ranking Overview of public monitoring status Regional Summaries East Asia ..................................................................................................... 14 China ........................................................................................ 15 South Korea ............................................................................... 16 Southeast Asia ............................................................................................. 17 Indonesia .................................................................................. 18 Thailand .................................................................................... 19 -

AQI Toolkit for Weathercasters

Endorsed by: EPA-456/B-05-001 November 2006 AQI Toolkit For Weathercasters U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Air Quality Planning and Standards Research Triangle Park, NC 27711 This Toolkit is available online at: www.airnow.gov 2 Printed on recycled paper Contents Acknowledgments . iii Toolkit Overview Your Role in Air Quality Awareness. 1 What’s in the Toolkit?. 1 Quick Prep . 2 Presentations Grades 3-5 . 3 Key Messages. 5 Notes Pages . 7 Student Handout. 9 Transparencies (see enclosed CD for PowerPoint presentation) . 13 Grades 6-8 . 15 Key Messages. 17 Notes Pages . 19 Student Handout. 21 Transparencies (see enclosed CD for PowerPoint presentation) . 25 Civic Groups . 27 Key Messages. 29 Long version: Civic Groups presentation . 31 Notes Pages. 33 Short version: Civic Groups presentation . 35 Notes Pages. 39 Handout for Civic Groups/Adults. 41 Optional Additional Activity for Civic Groups: Jeopardy Game . 45 Transparencies (see enclosed CD for PowerPoint presentation) Civic Groups — Long version . 49 Civic Groups — Short version . 51 Additional Resources for Weathercasters Air Pollution and Health. 53 Tips for Weathercasters . 55 Air Quality Index . 57 AirNow Air Quality Mapping and Forecasting . 61 Supplementary Air Quality Resources. 63 AQI Toolkit for Weathercasters i Contents Teacher Resources Introduction. 67 Air Quality Activities: Grades 3-5 . 71 Breathing, Exercise, and Air Pollution . 73 Particle Pollution: How Dirty Is the Air We Breathe? . 77 Air Pollution: What’s the Solution? — The Ozone Between Us. 79 Air Quality Activities: Grades 6-8 . 83 Tracking Air Quality . 85 Smog Alert . 99 “What’s Riding the Wind” in Your Community?. 103 Smog City . -

EPA Air Quality Index a Guide to Air Quality and Your Health

aqibro4x9collect.qxd 7/11/00 11:28 AM Page a United States EPA-454/R-00-005 Environmental Protection June 2000 Agency http://www.epa.gov Air and Radiation Washington, DC 20460 1EPA Air Quality Index A Guide to Air Quality and Your Health Printed on paper containing at least 2 30% postconsumer recovered fiber. aqibro4x9collect.qxd 7/11/00 11:28 AM Page c “Local air quality is unhealthy today.” Air Quality Index A Guide to Air Quality “It’s a code red day and Your Health for ozone.” Local air quality affects how we live and breathe. Like the weather, it can change from day to day or even hour to hour. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and others are working to make information about outdoor air quality as available to the public as Increasingly, radio, TV, and newspapers are information about the weather. A key tool in this effort providing information like this to local is the Air Quality Index, or AQI. EPA and local officials use the AQI to provide the public with timely and easy- communities. But what does it mean to you to-understand information on local air quality and ...if you plan to be outdoors that day? whether air pollution levels pose a health concern. ...if you have children who play outdoors? This booklet tells you about the AQI and how it is used to ...if you are retired? ...if you have asthma? provide air quality information. This booklet will help you understand what It also tells you about the possi- ble health effects of major air this information means to you and your family pollutants at various levels and and what you can do to protect your health. -

“How Can Planting Vegetation Enhance the Quality of Air, Water, and Soil in Fort Valley, Ga to Combat Environmental Justice Issues Due to Blue Bird Company?”

“HOW CAN PLANTING VEGETATION ENHANCE THE QUALITY OF AIR, WATER, AND SOIL IN FORT VALLEY, GA TO COMBAT ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE ISSUES DUE TO BLUE BIRD COMPANY?” Shakeena B. Reeves Fort Valley State University Fall 2020 FORT VALLEY WAS FOUNDED IN THE 1820S AS A NATIVE AMERICAN TRADING POST AT THE INTERSECTION OF TWO EARLY INDIAN TRAILS. FOUNDER JAMES EVERETT, WAS A WEALTHY AND INFLUENTIAL PLANTATION OWNER WAS DETERMINED TO HAVE THE TRAIN ROUTE IN HIS NEW TOWN. ON MARCH 23, 1856, FORT VALLEY WAS CHARTED BY A LEGISLATIVE ACT. BLUE BIRD CORPORATION (ORIGINALLY KNOWN AS THE BLUE BIRD BODY COMPANY) IS AN AMERICAN BUS MANUFACTURER FOUNDED IN 1932 IN FORT VALLEY, GA . BLUE BIRD CORPORATION WAS A GLOBAL WORLD LEADER IN SCHOOL BUS PRODUCTION IN THE EARLY AND MID 1900’S. BLUE BIRD CORPORATION WAS A FAMILY-OWNED BUSINESS UNTIL 1992. OVER THE PERIOD FROM 1987-1999, BLUE BIRD’S OPERATION IN FORT VALLEY REPORTED TO EPA THE RELEASE OF THOUSANDS OF POUNDS OF TOXIC AND DANGEROUS CHEMICALS INTO THE AIR ON AN ANNUAL BASE. BLUE BIRD’S OPERATION DOES EMIT FUGITIVE AND STACK AIR EMISSIONS AND GROUNDWATER EMISSIONS (IN THE FORM OF CONTAMINATION). THERE ARE ALSO OFFSITE SHIPMENTS OF TOXIC WASTE THAT PASS THROUGH THE COMMUNITY. http://www.movementech.org/gis/pdf/fortvalleyrpt.pdf Fort Valley was placed on the National Priorities List (NPL) in 1990 because of contaminated ground water and soils resulting from facility operations. EPA identified Blue Bird as a site PRPs; however, they were not required to conduct any cleanup. Index Fort Valley Georgia National Air -

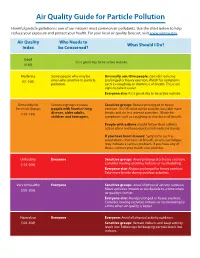

Air Quality Guide for Particle Pollution

Air Quality Guide for Particle Pollution Harmful particle pollution is one of our nation’s most common air pollutants. Use the chart below to help reduce your exposure and protect your health. For your local air quality forecast, visit www.airnow.gov Air Quality Who Needs to What Should I Do? Index be Concerned? Good It’s a great day to be active outside. (0-50) Moderate Some people who may be Unusually sensitive people: Consider reducing (51-100) unusually sensitive to particle prolonged or heavy exertion. Watch for symptoms pollution. such as coughing or shortness of breath. These are signs to take it easier. Everyone else: It’s a good day to be active outside. Unhealthy for Sensitive groups include Sensitive groups: Reduce prolonged or heavy Sensitive Groups people with heart or lung exertion. It’s OK to be active outside, but take more (101-150) disease, older adults, breaks and do less intense activities. Watch for children and teenagers. symptoms such as coughing or shortness of breath. People with asthma should follow their asthma action plans and keep quick relief medicine handy. If you have heart disease: Symptoms such as palpitations, shortness of breath, or unusual fatigue may indicate a serious problem. If you have any of these, contact your heath care provider. Unhealthy Everyone Sensitive groups: Avoid prolonged or heavy exertion. (151-200) Consider moving activities indoors or rescheduling. Everyone else: Reduce prolonged or heavy exertion. Take more breaks during outdoor activities. Very Unhealthy Everyone Sensitive groups: Avoid all physical activity outdoors. (201-300) Move activities indoors or reschedule to a time when air quality is better. -

Air Quality Index (AQI) (Pdf)

Air Quality Index (AQI) Air Quality Communication Workshop San Salvador, El Salvador April 16-17, 2012 How Do People Know What Particle Pollution Levels Are In their City or Country? • Air quality monitors measure PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations in g/m3 • Local, regional, and national governments decide how to disseminate monitor measurements to the public • Preferred way to communicate is via a color-coded Air Quality Index (AQI) that is easy for the public to understand 2 What is the Air Quality Index? • Index for reporting air quality • Color is key for communication • Ranges from 0 to 500 (no units) • Provides indicator of the quality of the air and its health effects • 101 typically corresponds to the level that violates the national health standard 3 Air Quality Index (AQI) AQI Value AQI Category AQI Color 0 - 50 Good Green 51 - 100 Moderate Yellow 101 - 150 Unhealthy for Sensitive Groups Orange 151 - 200 Unhealthy Red 201 - 300 Very Unhealthy Purple 301 - 500 Hazardous Maroon Daily Air Quality Standard4 AQI Health Messages AQI AQI Value Health Message Color 0 - 50 None Green Unusually sensitive people should reduce 51 - 100 Yellow prolonged or heavy exertion Sensitive groups should reduce prolonged 101 - 150 Orange or heavy exertion Sensitive groups should avoid prolonged 151 - 200 or heavy exertion; general public should Red reduce prolonged or heavy exertion Sensitive groups should avoid all physical 201 - 300 activity outdoors; general public should Purple avoid prolonged or heavy exertion Everyone should avoid all physical activity