Download This PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

138904 02 Classic.Pdf

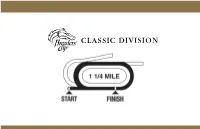

breeders’ cup CLASSIC BREEDERs’ Cup CLASSIC (GR. I) 30th Running Santa Anita Park $5,000,000 Guaranteed FOR THREE-YEAR-OLDS & UPWARD ONE MILE AND ONE-QUARTER Northern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 122 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs.; Southern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 117 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs. All Fillies and Mares allowed 3 lbs. Guaranteed $5 million purse including travel awards, of which 55% of all monies to the owner of the winner, 18% to second, 10% to third, 6% to fourth and 3% to fifth; plus travel awards to starters not based in California. The maximum number of starters for the Breeders’ Cup Classic will be limited to fourteen (14). If more than fourteen (14) horses pre-enter, selection will be determined by a combination of Breeders’ Cup Challenge winners, Graded Stakes Dirt points and the Breeders’ Cup Racing Secretaries and Directors panel. Please refer to the 2013 Breeders’ Cup World Championships Horsemen’s Information Guide (available upon request) for more information. Nominated Horses Breeders’ Cup Racing Office Pre-Entry Fee: 1% of purse Santa Anita Park Entry Fee: 1% of purse 285 W. Huntington Dr. Arcadia, CA 91007 Phone: (859) 514-9422 To Be Run Saturday, November 2, 2013 Fax: (859) 514-9432 Pre-Entries Close Monday, October 21, 2013 E-mail: [email protected] Pre-entries for the Breeders' Cup Classic (G1) Horse Owner Trainer Declaration of War Mrs. John Magnier, Michael Tabor, Derrick Smith & Joseph Allen Aidan P. O'Brien B.c.4 War Front - Tempo West by Rahy - Bred in Kentucky by Joseph Allen Flat Out Preston Stables, LLC William I. -

German Translation of Press Release Dated January 20, 2004 Magna Gibt

German translation of press release dated January 20, 2004 Magna gibt personelle Veränderungen an der Führungsspitze bekannt AURORA, Ontario - Wie die Magna International Inc. (TSX: MG.A, MG.B, NYSE: MGA) heute bekannt gab, hat Belinda Stronach ihre Ämter als President und Chief Executive Officer des Unternehmens mit sofortiger Wirkung niedergelegt. Frank Stronach übernimmt auf Interimsbasis die Position des President. Der Vorstand des Unternehmens hat unterdessen einen Sonderausschuss eingerichtet, der gemeinsam mit Frank Stronach innerhalb und ausserhalb des Konzerns nach einem Nachfolger für Frau Stronach suchen wird. Frank Stronach, Chairman von Magna, erklärte: "Im Namen des Vorstands und der Mitarbeiter des Unternehmens möchte ich Belinda meinen Dank für den herausragenden Beitrag aussprechen, den sie als President und CEO für unsere Aktionäre, Kunden und Beschäftigten geleistet hat." Stronach weiter: "Magna wird partnerschaftlich geführt. Andere Mitglieder im Managementteam, vor allem Manfred Gingl, Siegfried Wolf und Vince Galifi, werden nun grössere Aufgabenbereiche übernehmen." "Unter Frau Stronachs Führung hat Magna Wachstum und Gewinne in Rekordhöhe erzielt", so Ed Lumley, Lead Director im Vorstand des Unternehmens. "Sie hat einen wesentlichen Beitrag zum Wohle von Magna und seinen Tochtergesellschaften geleistet. Der Vorstand wünscht ihr für ihre berufliche Zukunft alles Gute." "Ich möchte allen Mitarbeitern von Magna für ihre Unterstützung danken", erklärte Belinda Stronach. "Magna und seine Tochtergesellschaften haben hervorragende Mitarbeiter und starke Führungsteams. Magna ist heute in einer guten Position, um auch in der Zukunft robuste Betriebsergebnisse zu zielen. Ich bin zuversichtlich, dass Magna auch weiterhin die Konkurrenz weit hinter sich lassen wird." Frau Stronach legte auch ihre Ämter als Vorstandsmitglied von Magna und als Vorstandsmitglied der Decoma International Inc., der Intier Automotive Inc. -

Teen Voters: the Austrian Experience

PRZEGLĄD ZACHODNI 2018 KATARZYNA GELLES Wrocław TEEN VOTERS: THE AUSTRIAN EXPERIENCE For a democratic country general elections are a process of a fundamental na- ture. They enable all eligible citizens to participate on equal terms in shaping their country’s politics. Therefore, in the analysis of a selected party system it is not only the actors on the political stage (primarily the political parties) that are important but also the support they enjoy in society. After all, their electoral success and ability to exercise power are dependent on the electorate’s decision. Of equal merit is the issue of voter turnout, which is defined as “the ratio of votes cast to registered voters”.1 Whether the turnout is high or low, it always provokes questions about the reasons for this state of affairs as in a democratic system it is always indicative of civic maturity. In recent years in Europe there has been increasing talk of the crisis of democracy. One of its most noticeable syndromes is decreased voter turnout, which fell below 70% after 1990.2 This phenomenon occurs on a broad scale and its reasons have been analysed by political scientists and sociologists. Among the most oft-cited causes is “politics fatigue”, i.e. a lack of interest in political life displayed by citizens, for whom the differences between political groups and factions are becoming less and less clear. Voters are also losing faith in their effectiveness, often assuming that election results do not exert a visible impact on the surrounding reality. People resignedly say: “those at the top will do what they want to”. -

Notice of Annual Meeting Management Information Circular/Proxy Statement

Notice of Annual Meeting Management Information Circular/Proxy Statement Annual Meeting May 4, 2011 BODY & CHASSIS SYSTEMS | POWERTRAIN SYSTEMS | EXTERIOR SYSTEMS www.magna.com SEATING SYSTEMS | INTERIOR SYSTEMS | VISION SYSTEMS | CLOSURE SYSTEMS | ROOF SYSTEMS | ELECTRONIC SYSTEMS | HYBRID & ELECTRIC VEHICLES/SYSTEMS | VEHICLE ENGINEERING & CONTRACT ASSEMBLY 24MAR201113335785 Magna International Inc. 337 Magna Drive 24MAR200901113112 Aurora, Ontario, Canada L4G 7K1 Telephone: (905) 726-2462 Legal Fax: (905) 726-7164 March 30, 2011 Dear Shareholder, I am pleased to invite you to attend Magna’s 2011 Annual Meeting of Shareholders on May 4, 2011 at 10:00 a.m. (Toronto time) at the Hilton Suites Toronto/Markham Conference Centre, 8500 Warden Avenue, Markham, Ontario, Canada. The business items which will be addressed at the annual meeting are set out in the notice of annual meeting and the accompanying proxy circular. We encourage you to vote your shares in person, or by phone, fax or internet, as described in the proxy circular. As in prior years, those not attending the annual meeting in person can access a simultaneous webcast through Magna’s website (www.magna.com). As you are aware, 2010 was a year of significant change for Magna. In August 2010, Magna completed the plan of arrangement and related transactions (the ‘‘Arrangement’’) announced in May 2010. The Arrangement, which was approved by over 75% of Magna’s disinterested shareholders, represented an historic milestone for Magna as it collapsed the dual-class share structure which had been in place since 1978. In conjunction with the Arrangement, the consulting, business development and business services agreements through which Frank Stronach has provided his knowledge and expertise to Magna and its divisions were amended to extend the expiry date of each agreement to December 31, 2014, after which they will automatically terminate. -

The Mainstream Right, the Far Right, and Coalition Formation in Western Europe by Kimberly Ann Twist a Dissertation Submitted In

The Mainstream Right, the Far Right, and Coalition Formation in Western Europe by Kimberly Ann Twist A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Jonah D. Levy, Chair Professor Jason Wittenberg Professor Jacob Citrin Professor Katerina Linos Spring 2015 The Mainstream Right, the Far Right, and Coalition Formation in Western Europe Copyright 2015 by Kimberly Ann Twist Abstract The Mainstream Right, the Far Right, and Coalition Formation in Western Europe by Kimberly Ann Twist Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley Professor Jonah D. Levy, Chair As long as far-right parties { known chiefly for their vehement opposition to immigration { have competed in contemporary Western Europe, scholars and observers have been concerned about these parties' implications for liberal democracy. Many originally believed that far- right parties would fade away due to a lack of voter support and their isolation by mainstream parties. Since 1994, however, far-right parties have been included in 17 governing coalitions across Western Europe. What explains the switch from exclusion to inclusion in Europe, and what drives mainstream-right parties' decisions to include or exclude the far right from coalitions today? My argument is centered on the cost of far-right exclusion, in terms of both office and policy goals for the mainstream right. I argue, first, that the major mainstream parties of Western Europe initially maintained the exclusion of the far right because it was relatively costless: They could govern and achieve policy goals without the far right. -

Stronach Wins Riding-Barely Belinda Stronach Has a Job for I Have the Support of the the Next Four Years

Sending Your Teen To Us For 4 Days This Summer Could Save Their Life. Your local source for... Next Course Insurance Starts July 20th/04 Investments Wealth Management 905 727 4605 www.hsfinancial.ca 905-726-4132 Aurora’s Community Newspaper Representing email • [email protected] Vol. 4 No. 36 Week of June 29, 2004 905-727-3300 Stronach wins riding-barely Belinda Stronach has a job for I have the support of the the next four years. community. But only barely. “I’m in it for the long haul,” she Following Monday’s Federal told The Auroran in an exclusive election, in which Stronach battled interview. to victory in the new riding of Since January, Stronach has Newmarket-Aurora, the popular been running - sometimes literally blonde who made sure everyone - for this political position. knew she was born and raised in She put a spark into the newly the Newmarket-Aurora area, formed Conservative Party of breathed a sigh of relief. Canada when she announced she “I never took anything for grant- would seek the leadership. ed,” she told The Auroran. “I ran Suddenly, the woman who was this race believing I was always 10 Chief Executive Officer of Magna points behind.” International became a national And, apparently, she was. figure. Late numbers put her only She finished a respectable about 500 votes ahead of Liberal second behind Stephen Harper, Martha Hall Findlay and with only who lost out being Canada’s next a few polls to be heard from, sug- prime minister as the voters decid- gested Stronach was the narrow ed to stay “with the devil” they winner. -

Belinda Stronach? National Newspaper Coverage of the Conservative Party of Canada’S 2004 Leadership Race

Who Framed Belinda Stronach? National Newspaper Coverage of the Conservative Party of Canada’s 2004 Leadership Race Paper presented to the 2005 Canadian Political Science Association Conference London, Ontario June 4, 2005 Linda Trimble, Professor Political Science Department University of Alberta 12-26 HM Tory Bldg. Edmonton, Alberta T6G 2H4 [email protected] 2 Who Framed Belinda Stronach? National Newspaper Coverage of the Conservative Party of Canada’s 2004 Leadership Race Paper presented to the 2005 Canadian Political Science Association Conference London, Ontario June 4, 2005 Linda Trimble, Professor Political Science Department University of Alberta 12-26 HM Tory Bldg. Edmonton, Alberta T6G 2H4 [email protected] Abstract If masculine norms define political leadership roles and shape media coverage of leadership contests they are likely to be revealed by press coverage of serious challenges by women for the leadership of competitive political parties. The new Conservative Party of Canada’s inaugural leadership race featured such a candidate, Belinda Stronach. While Stronach lost the leadership to Stephen Harper on the first ballot, she ran a well-financed, staffed and organized campaign, enjoyed considerable backing from party insiders, and placed a respectable second. This paper reports the results of a content analysis of all news stories, opinion pieces, editorials and columns published about the leadership race in Canada’s national newspapers, the Globe and Mail and the National Post, from January 13 to March 22, 2004. It reveals striking differences in the amount of coverage accorded the candidates, as well as sexist framing and gendered evaluations of the female candidate. While Belinda Stronach’s campaign received a plethora of media attention, a considerable amount of it scrutinized her looks, wardrobe, sexual availability and personal background while mocking her leadership aspirations and deriding her qualifications for political office. -

Austrian Populism and the Not-So-Great Recession. the Primacy of Politics1

Austrian populism and the not-so-great Recession. The primacy of politics Kurt Richard Luther [email protected] Keele European Parties Research Unit (KEPRU) Working Paper 38 © Kurt Richard Luther, 2014 2 ISSN 1475-15701 ISBN 1-899488-77-6 KEPRU Working Papers are published by: School of Politics, International Relations and Philosophy (SPIRE) Keele University Staffs ST5 5BG, UK Fax +44 (0)1782 73 3592 www.keele.ac.uk/kepru Editor: Prof Kurt Richard Luther ([email protected]) KEPRU Working Papers are available via KEPRU’s website. ___________________________________________________________________ Launched in September 2000, the Keele European Parties Research Unit (KEPRU) was the first research grouping of its kind in the UK. It brings together the hitherto largely independent work of Keele researchers focusing on European political parties, and aims: • to facilitate its members' engagement in high-quality academic research, individually, collectively in the Unit and in collaboration with cognate research groups and individuals in the UK and abroad; • to hold regular conferences, workshops, seminars and guest lectures on topics related to European political parties; • to publish a series of parties-related research papers by scholars from Keele and elsewhere; • to expand postgraduate training in the study of political parties, principally through Keele's MA in Parties and Elections and the multinational PhD summer school, with which its members are closely involved; • to constitute a source of expertise on European parties and party politics for media and other interests. Convenor KEPRU: Prof Kurt Richard Luther ([email protected]) Kurt Richard Luther is Professor of Comparative Politics at Keele University 3 Austrian populism and the not-so-great Recession. -

Information Guide Euroscepticism

Information Guide Euroscepticism A guide to information sources on Euroscepticism, with hyperlinks to further sources of information within European Sources Online and on external websites Contents Introduction .................................................................................................. 2 Brief Historical Overview................................................................................. 2 Euro Crisis 2008 ............................................................................................ 3 European Elections 2014 ................................................................................ 5 Euroscepticism in Europe ................................................................................ 8 Eurosceptic organisations ......................................................................... 10 Eurosceptic thinktanks ............................................................................. 10 Transnational Eurosceptic parties and political groups .................................. 11 Eurocritical media ................................................................................... 12 EU Reaction ................................................................................................. 13 Information sources in the ESO database ........................................................ 14 Further information sources on the internet ..................................................... 14 Copyright © 2016 Cardiff EDC. All rights reserved. 1 Cardiff EDC is part of the University Library -

Challenger Party List

Appendix List of Challenger Parties Operationalization of Challenger Parties A party is considered a challenger party if in any given year it has not been a member of a central government after 1930. A party is considered a dominant party if in any given year it has been part of a central government after 1930. Only parties with ministers in cabinet are considered to be members of a central government. A party ceases to be a challenger party once it enters central government (in the election immediately preceding entry into office, it is classified as a challenger party). Participation in a national war/crisis cabinets and national unity governments (e.g., Communists in France’s provisional government) does not in itself qualify a party as a dominant party. A dominant party will continue to be considered a dominant party after merging with a challenger party, but a party will be considered a challenger party if it splits from a dominant party. Using this definition, the following parties were challenger parties in Western Europe in the period under investigation (1950–2017). The parties that became dominant parties during the period are indicated with an asterisk. Last election in dataset Country Party Party name (as abbreviation challenger party) Austria ALÖ Alternative List Austria 1983 DU The Independents—Lugner’s List 1999 FPÖ Freedom Party of Austria 1983 * Fritz The Citizens’ Forum Austria 2008 Grüne The Greens—The Green Alternative 2017 LiF Liberal Forum 2008 Martin Hans-Peter Martin’s List 2006 Nein No—Citizens’ Initiative against -

Compensation, Austerity, and Populism

PRELIMINARY VERSION: PLEASE DO NOT QUOTE Compensation, Austerity, and Populism: Social Spending and Voting in 17 Western European Countries Chase Foster Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs Brown University [email protected] Jeffry Frieden Department of Government Harvard University [email protected] Abstract The existence of comprehensive social policies to compensate those who might be harmed by integration is widely seen as an important precondition for public support for economic and political integration in western Europe. However, many western European countries reduced spending on income maintenance after 1990. In countries hard hit by the sovereign debt crisis, there have also been significant cuts to social services. We evaluate the impact of levels of social spending on public support for populist parties. We also evaluate the impact of austerity measures on support for such parties. We examine a panel of 187 elections from 1990-2017 and analyze pooled cross-sectional data from eight waves of the European Social Survey. We find evidence that populist parties fare worse where countries spend more on social support, and where spending has not been reduced from historical levels. On the other hand, where countries spend less on income maintenance, and/or have decreased spending from earlier levels, populist vote shares are consistently higher, and the likelihood of supporting populist parties greater. This relationship holds when controlling for a range of individual and macroeconomic factors, including occupational and educational characteristics, unemployment, economic growth, and immigration rates. The growing strength of populist political parties is rooted in long-term economic and cultural changes, but appropriate social policies may moderate their appeal. -

French Translation of Press Release Dated September 29, 2004 Magna

French translation of press release dated September 29, 2004 Magna conclut l'acquisition de New Venture Gear AURORA, Ontario Magna International Inc. (MG.A et MG.B à la Bourse de Toronto et MGA à la Bourse de New York) a conclu l'acquisition des activités mondiales de la filiale en propriété exclusive de DaimlerChrysler Corporation, New Venture Gear, Inc. ("NVG"). L'opération, annoncée le 17 mai 2004, porte sur la création d'une nouvelle coentreprise, désignée New Process Gear, Inc. A l'origine propriété à 80 % de Magna et à 20 % de DaimlerChrysler Corporation, cette coentreprise exploite des installations de fabrication à Syracuse, dans l'État de New York. Magna acquerra la participation de DaimlerChrysler Corporation dans New Process Gear, Inc. en septembre 2007. L'opération implique également l'acquisition par Magna de certains autres actifs américains et européens de NVG, y compris des installations de fabrication à Roitzsch, en Allemagne, et un centre de recherche et développement de même qu'une agence à Troy, au Michigan. Les approbations des autorités antitrust des Etats-Unis et d'Europe ont été obtenues récemment et les deux unités de négociation des TUA ont ratifié une nouvelle convention collective hier. Le prix d'achat de la totalité des activités de NVG s'élève à environ 431 million de dollars américains, sous réserve des ajustements après clôture. Dans le cadre de l'opération décrite ci-dessus, Magna a émis des billets de premier rang à coupon zéro non garantis, pour un prix d'émission total de 365 millions de dollars canadiens et un montant total exigible à échéance de 415 millions de dollars canadiens.