Was Magna in the Public Interest? Anita Anand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

138904 02 Classic.Pdf

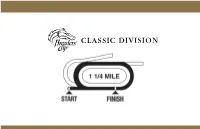

breeders’ cup CLASSIC BREEDERs’ Cup CLASSIC (GR. I) 30th Running Santa Anita Park $5,000,000 Guaranteed FOR THREE-YEAR-OLDS & UPWARD ONE MILE AND ONE-QUARTER Northern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 122 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs.; Southern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 117 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs. All Fillies and Mares allowed 3 lbs. Guaranteed $5 million purse including travel awards, of which 55% of all monies to the owner of the winner, 18% to second, 10% to third, 6% to fourth and 3% to fifth; plus travel awards to starters not based in California. The maximum number of starters for the Breeders’ Cup Classic will be limited to fourteen (14). If more than fourteen (14) horses pre-enter, selection will be determined by a combination of Breeders’ Cup Challenge winners, Graded Stakes Dirt points and the Breeders’ Cup Racing Secretaries and Directors panel. Please refer to the 2013 Breeders’ Cup World Championships Horsemen’s Information Guide (available upon request) for more information. Nominated Horses Breeders’ Cup Racing Office Pre-Entry Fee: 1% of purse Santa Anita Park Entry Fee: 1% of purse 285 W. Huntington Dr. Arcadia, CA 91007 Phone: (859) 514-9422 To Be Run Saturday, November 2, 2013 Fax: (859) 514-9432 Pre-Entries Close Monday, October 21, 2013 E-mail: [email protected] Pre-entries for the Breeders' Cup Classic (G1) Horse Owner Trainer Declaration of War Mrs. John Magnier, Michael Tabor, Derrick Smith & Joseph Allen Aidan P. O'Brien B.c.4 War Front - Tempo West by Rahy - Bred in Kentucky by Joseph Allen Flat Out Preston Stables, LLC William I. -

German Translation of Press Release Dated January 20, 2004 Magna Gibt

German translation of press release dated January 20, 2004 Magna gibt personelle Veränderungen an der Führungsspitze bekannt AURORA, Ontario - Wie die Magna International Inc. (TSX: MG.A, MG.B, NYSE: MGA) heute bekannt gab, hat Belinda Stronach ihre Ämter als President und Chief Executive Officer des Unternehmens mit sofortiger Wirkung niedergelegt. Frank Stronach übernimmt auf Interimsbasis die Position des President. Der Vorstand des Unternehmens hat unterdessen einen Sonderausschuss eingerichtet, der gemeinsam mit Frank Stronach innerhalb und ausserhalb des Konzerns nach einem Nachfolger für Frau Stronach suchen wird. Frank Stronach, Chairman von Magna, erklärte: "Im Namen des Vorstands und der Mitarbeiter des Unternehmens möchte ich Belinda meinen Dank für den herausragenden Beitrag aussprechen, den sie als President und CEO für unsere Aktionäre, Kunden und Beschäftigten geleistet hat." Stronach weiter: "Magna wird partnerschaftlich geführt. Andere Mitglieder im Managementteam, vor allem Manfred Gingl, Siegfried Wolf und Vince Galifi, werden nun grössere Aufgabenbereiche übernehmen." "Unter Frau Stronachs Führung hat Magna Wachstum und Gewinne in Rekordhöhe erzielt", so Ed Lumley, Lead Director im Vorstand des Unternehmens. "Sie hat einen wesentlichen Beitrag zum Wohle von Magna und seinen Tochtergesellschaften geleistet. Der Vorstand wünscht ihr für ihre berufliche Zukunft alles Gute." "Ich möchte allen Mitarbeitern von Magna für ihre Unterstützung danken", erklärte Belinda Stronach. "Magna und seine Tochtergesellschaften haben hervorragende Mitarbeiter und starke Führungsteams. Magna ist heute in einer guten Position, um auch in der Zukunft robuste Betriebsergebnisse zu zielen. Ich bin zuversichtlich, dass Magna auch weiterhin die Konkurrenz weit hinter sich lassen wird." Frau Stronach legte auch ihre Ämter als Vorstandsmitglied von Magna und als Vorstandsmitglied der Decoma International Inc., der Intier Automotive Inc. -

Notice of Annual Meeting Management Information Circular/Proxy Statement

Notice of Annual Meeting Management Information Circular/Proxy Statement Annual Meeting May 4, 2011 BODY & CHASSIS SYSTEMS | POWERTRAIN SYSTEMS | EXTERIOR SYSTEMS www.magna.com SEATING SYSTEMS | INTERIOR SYSTEMS | VISION SYSTEMS | CLOSURE SYSTEMS | ROOF SYSTEMS | ELECTRONIC SYSTEMS | HYBRID & ELECTRIC VEHICLES/SYSTEMS | VEHICLE ENGINEERING & CONTRACT ASSEMBLY 24MAR201113335785 Magna International Inc. 337 Magna Drive 24MAR200901113112 Aurora, Ontario, Canada L4G 7K1 Telephone: (905) 726-2462 Legal Fax: (905) 726-7164 March 30, 2011 Dear Shareholder, I am pleased to invite you to attend Magna’s 2011 Annual Meeting of Shareholders on May 4, 2011 at 10:00 a.m. (Toronto time) at the Hilton Suites Toronto/Markham Conference Centre, 8500 Warden Avenue, Markham, Ontario, Canada. The business items which will be addressed at the annual meeting are set out in the notice of annual meeting and the accompanying proxy circular. We encourage you to vote your shares in person, or by phone, fax or internet, as described in the proxy circular. As in prior years, those not attending the annual meeting in person can access a simultaneous webcast through Magna’s website (www.magna.com). As you are aware, 2010 was a year of significant change for Magna. In August 2010, Magna completed the plan of arrangement and related transactions (the ‘‘Arrangement’’) announced in May 2010. The Arrangement, which was approved by over 75% of Magna’s disinterested shareholders, represented an historic milestone for Magna as it collapsed the dual-class share structure which had been in place since 1978. In conjunction with the Arrangement, the consulting, business development and business services agreements through which Frank Stronach has provided his knowledge and expertise to Magna and its divisions were amended to extend the expiry date of each agreement to December 31, 2014, after which they will automatically terminate. -

Stronach Wins Riding-Barely Belinda Stronach Has a Job for I Have the Support of the the Next Four Years

Sending Your Teen To Us For 4 Days This Summer Could Save Their Life. Your local source for... Next Course Insurance Starts July 20th/04 Investments Wealth Management 905 727 4605 www.hsfinancial.ca 905-726-4132 Aurora’s Community Newspaper Representing email • [email protected] Vol. 4 No. 36 Week of June 29, 2004 905-727-3300 Stronach wins riding-barely Belinda Stronach has a job for I have the support of the the next four years. community. But only barely. “I’m in it for the long haul,” she Following Monday’s Federal told The Auroran in an exclusive election, in which Stronach battled interview. to victory in the new riding of Since January, Stronach has Newmarket-Aurora, the popular been running - sometimes literally blonde who made sure everyone - for this political position. knew she was born and raised in She put a spark into the newly the Newmarket-Aurora area, formed Conservative Party of breathed a sigh of relief. Canada when she announced she “I never took anything for grant- would seek the leadership. ed,” she told The Auroran. “I ran Suddenly, the woman who was this race believing I was always 10 Chief Executive Officer of Magna points behind.” International became a national And, apparently, she was. figure. Late numbers put her only She finished a respectable about 500 votes ahead of Liberal second behind Stephen Harper, Martha Hall Findlay and with only who lost out being Canada’s next a few polls to be heard from, sug- prime minister as the voters decid- gested Stronach was the narrow ed to stay “with the devil” they winner. -

Belinda Stronach? National Newspaper Coverage of the Conservative Party of Canada’S 2004 Leadership Race

Who Framed Belinda Stronach? National Newspaper Coverage of the Conservative Party of Canada’s 2004 Leadership Race Paper presented to the 2005 Canadian Political Science Association Conference London, Ontario June 4, 2005 Linda Trimble, Professor Political Science Department University of Alberta 12-26 HM Tory Bldg. Edmonton, Alberta T6G 2H4 [email protected] 2 Who Framed Belinda Stronach? National Newspaper Coverage of the Conservative Party of Canada’s 2004 Leadership Race Paper presented to the 2005 Canadian Political Science Association Conference London, Ontario June 4, 2005 Linda Trimble, Professor Political Science Department University of Alberta 12-26 HM Tory Bldg. Edmonton, Alberta T6G 2H4 [email protected] Abstract If masculine norms define political leadership roles and shape media coverage of leadership contests they are likely to be revealed by press coverage of serious challenges by women for the leadership of competitive political parties. The new Conservative Party of Canada’s inaugural leadership race featured such a candidate, Belinda Stronach. While Stronach lost the leadership to Stephen Harper on the first ballot, she ran a well-financed, staffed and organized campaign, enjoyed considerable backing from party insiders, and placed a respectable second. This paper reports the results of a content analysis of all news stories, opinion pieces, editorials and columns published about the leadership race in Canada’s national newspapers, the Globe and Mail and the National Post, from January 13 to March 22, 2004. It reveals striking differences in the amount of coverage accorded the candidates, as well as sexist framing and gendered evaluations of the female candidate. While Belinda Stronach’s campaign received a plethora of media attention, a considerable amount of it scrutinized her looks, wardrobe, sexual availability and personal background while mocking her leadership aspirations and deriding her qualifications for political office. -

French Translation of Press Release Dated September 29, 2004 Magna

French translation of press release dated September 29, 2004 Magna conclut l'acquisition de New Venture Gear AURORA, Ontario Magna International Inc. (MG.A et MG.B à la Bourse de Toronto et MGA à la Bourse de New York) a conclu l'acquisition des activités mondiales de la filiale en propriété exclusive de DaimlerChrysler Corporation, New Venture Gear, Inc. ("NVG"). L'opération, annoncée le 17 mai 2004, porte sur la création d'une nouvelle coentreprise, désignée New Process Gear, Inc. A l'origine propriété à 80 % de Magna et à 20 % de DaimlerChrysler Corporation, cette coentreprise exploite des installations de fabrication à Syracuse, dans l'État de New York. Magna acquerra la participation de DaimlerChrysler Corporation dans New Process Gear, Inc. en septembre 2007. L'opération implique également l'acquisition par Magna de certains autres actifs américains et européens de NVG, y compris des installations de fabrication à Roitzsch, en Allemagne, et un centre de recherche et développement de même qu'une agence à Troy, au Michigan. Les approbations des autorités antitrust des Etats-Unis et d'Europe ont été obtenues récemment et les deux unités de négociation des TUA ont ratifié une nouvelle convention collective hier. Le prix d'achat de la totalité des activités de NVG s'élève à environ 431 million de dollars américains, sous réserve des ajustements après clôture. Dans le cadre de l'opération décrite ci-dessus, Magna a émis des billets de premier rang à coupon zéro non garantis, pour un prix d'émission total de 365 millions de dollars canadiens et un montant total exigible à échéance de 415 millions de dollars canadiens. -

The Publisher's Page

Our 44th Year Our 44th Year EX ECUT IVE GOLFER ® PAZDUR PUBLISHING The Publisher’s Page e America’s only national magazine published exclusively 2171 Campus Drive, Suite 330 g for private country club executive golfers Irvine, California 92612 a HE OLDEN ULE PH: (949) 752-6474 FAX: (949) 752-0398 T G R ADMINISTRATION P WEBSITE : EXECUTIVEGOLFERMAGAZINE.COM Frank with his horse, Frank Stronach, founder of the Mark E. Pazdur Ghostzapper, in 2004 s ’ Publisher NOVEMBER 2016 VOL. 44 NUMBER 314 after winning the r $30 billion in sales Magna International, Theda Ahern Pazdur Breeders’ Cup Classic e discusses living under the boot of two of the President & cfo at Lone Star Park h G. David Piper CORPORATE OFFICERS & in Texas. s most brutal regimes, true hunger, and the certified Public AccountAnt BOARD DIRECTORS i l hardship of discrimination. EDITORIAL/MANAGEMENT Edward F. Pazdur b chAirMAn, ceo & founder HONORARY LIFE MEMBER, PGA OF AMERICA SC u Mark E. Pazdur HONOREE: 2007 HAWAII HONU AWARD By Mark Pazdur, Publisher editor in chief P Theda Ahern Pazdur Theda Ahern Pazdur President, cfo & co-founder Art director e OCALA, FLORIDA: The sound of gunfire is still fresh in Mark E. Pazdur h Joyce Stevens Frank Stronach’s memory more than a half century later. Publisher & senior Vice President MAnAging editor T “As a young child, I was exposed to the atrocities of Hitler JoAnn Pazdur SUBSCRIPTION DEPARTMENT and the Nazi regime,” emotionally recalled Stronach. “My home dePuty editor country of Austria was devastated by the war. The front lines of Netta Riffel grAPhic designer HAVE EXECUTIVE GOLFER SENT battle made it as close as three miles to the outskirts of our small Nikki Haydin TO YOUR HOME town at the foot of the Alps before the allies prevailed. -

Magna International, Inc Canada

Magna International, Inc Canada The Challenge of Integration into Global Supply Chains Written by Charles Gastle Founding Partner Bennett Gastle Professional Corporation, Barristers & Solicitors and Heather Gastle1 The case was developed with the cooperation of Magna International solely for educational purposes as a contribution to the project entitled ―IPR Strategies for Emerging Enterprises — Capacity Building for Successful Entry to Global Supply Chain,‖ conducted under the auspices of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC). The case is neither designed nor intended to illustrate the correct or incorrect management of the situation or issues contained in the case. Reproduction and duplication of this case for personal and educational use is encouraged. No part of this case however can be reproduced, stored, or used for purposes other than the above without the written permission of the author(s) and APEC. © 2010 APEC Secretariat 20 Canada Introduction In 2009 there was a limited number of major automobile manufacturers (OEMs) such as Ford, General Motors and Toyota, and the competition for their business was intense among the major autoparts suppliers. Innovation in the design of automotive parts and manufacturing processes was crucial to securing new contracts as automobile models changed and technology evolved. Innovation and design also played an important role in achieving the price milestones established in the contracts that existed ―at will‖ with the major OEMs, which meant that they were subject to cancellation at any time. An industry marked by constant innovation required special corporate processes to recognize an innovative idea that had value and to commercialize it. Magna International Inc. 2 (Magna) was the leading automobile parts manufacturer in North America with sales exceeding $20 billion. -

Stronach Frank

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM SC 13D/A Schedule filed to report acquisition of beneficial ownership of 5% or more of a class of equity securities [amend] Filing Date: 2011-02-02 SEC Accession No. 0001193125-11-022049 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILED BY STRONACH FRANK Mailing Address 337 MAGNA DRIVE CIK:903977 AURORA ONTARIO CANADA Type: SC 13D/A A6 L4G7K1 SUBJECT COMPANY MI DEVELOPMENTS INC Mailing Address Business Address 455 MAGNA DR 455 MAGNA DR CIK:1252509| IRS No.: 000000000 | State of Incorp.:A6 | Fiscal Year End: 1231 AURORA ONTARIO AURORA ONTARIO Type: SC 13D/A | Act: 34 | File No.: 005-79210 | Film No.: 11567648 CANADA A6 L4G7A9 CANADA A6 L4G7A9 SIC: 7948 Racing, including track operation 9057136322 Copyright © 2012 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 SCHEDULE 13D/A Under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (Amendment No. 19)* MI Developments Inc. (Name of Issuer) Class A Subordinate Voting Shares (Title of Class of Securities) 55304X 10 4 (CUSIP Number) Kenneth G. Alberstadt Akerman Senterfitt LLP 335 Madison Avenue, Suite 2600 New York, NY 10017 (212) 880-3817 (Name, Address and Telephone Number of Person Authorized to Receive Notices and Communications) January 31, 2011 (Date of Event Which Requires Filing of this Statement) If the filing person has previously filed a statement on Schedule 13G to report the acquisition that is the subject of this Schedule 13D, and is filing this schedule because of §§240.13d-1(e), 240.13d-1(f) or 240.13d-1(g), check the following box. -

THOROUGHBRED TIMES Inside Pluck Training Well Toward ® Fountain of Youth Notes, P

International THOROUGHBRED TIMES Inside Pluck training well toward ® Fountain of Youth notes, p. 2 European classic target, page 11 Kathmanblu, p. 3 Five Minutes With…, p. 4 Pedigree Patterns, p. 5 Tuesday, Buena Vista H. recap, p. 6 February 22, 2011 TAn international daily newsletterDAY for THOROUGHBRED TIMES subscribers Archarcharch bounces back, beats J P’s Gusto in Southwest After a disappointing effort in the fog in the Smarty Jones Stakes, “He was a different horse today,” Yagos Road to the Archarcharch made amends with a one-length score at odds of 14.50- said. “He was a little rank [in the Smarty ® to-1 in the $250,000 Southwest Jones] and he’s a horse who wants to sit off TRIPLE CROWN Sponsored by Stakes on Monday at Oaklawn Park. the pace a little bit, so when he got pushed The three-year-old colt by Arch, around a little bit he got keyed up and put himself on the lead. On that sire of 2010 Breeders’ Cup Classic track that day, it was so tiring. He pretty much wore himself out that day.” (G1) winner and champion older Jon Court rated Archarcharch, the sixth betting choice, in fifth, then male Blame, spurted clear in the fourth, before angling him five wide in the stretch for his winning rally. stretch of the one-mile race and held With the Southwest victory, Archarcharch picked up $150,000 in off a late surge from Grade 1 win- graded stakes earnings, which is used to determine the field for the ner J P’s Gusto to prevail in 1:38.23 Kentucky Derby Presented by Yum! Brands (G1) if more than 20 three- on a track rated as fast. -

List of Canadians by Net Worth - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia List of Canadians by Net Worth from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

21/9/2014 List of Canadians by net worth - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia List of Canadians by net worth From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The following is a list of Canadians by net worth: Contents 1 Richest Canadians (2013 statistics) 2 Richest Canadians (2012 statistics) 3 Richest Canadians (2011 statistics) 4 Richest Canadians (2010 statistics) 5 Richest Canadians (2009 statistics) 6 References 7 External links Richest Canadians (2013 statistics) Updated November 23, 2013.[1] Legend Icon Description Has not changed since the 2012 ranking. Has increased since the 2012 ranking. Has decreased since the 2012 ranking. Net worth Home Sources of No. Name Age Residence (CAD) Province wealth Thomson David Thomson, 3rd Reuters, 1 Baron Thomson of $26.10 billion 56 Ontario Toronto, Ontario Woodbridge Co. Fleet and family Ltd George Weston Ltd., Loblaw 2 Galen Weston $10.40 billion 73 Ontario Toronto, Ontario Cos. Ltd, Holt Renfrew Arthur Irving, James New Saint John, New Irving Oil Ltd., 3 $7.85 billion — Irving, John Irving Brunswick Brunswick J.D. Irving Ltd. Edward Rogers III and Rogers 4 $7.60 billion 44 Ontario Toronto, Ontario http://en.wikipfeadmia.iolryg/wiki/List_of_Canadians_by_net_worth Communication1/s21 21/9/2014 List of Canadians by net worth - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia family Communications Vancouver, British Jim Pattison 5 Jim Pattison $7.39 billion 85 British Columbia Group Columbia Montreal, 6 Lino Saputo and family $5.24 billion 76 Quebec Saputo Inc. Quebec Montreal, Power Corp. of 7 Paul Desmarais $4.93 billion 86 Quebec Quebec Canada eBay Inc., Palo Alto, 8 Jeffrey Skoll $4.92 billion 48 Quebec Participant California Media James James Armstrong Winnipeg, 9 $4.45 billion — Richardson & Richardson and family Manitoba Manitoba Sons Ltd. -

Austria͛s Internaional Posiion After the End Of

ƵƐƚƌŝĂ͛Ɛ/ŶƚĞƌŶĂƟŽŶĂůWŽƐŝƟŽŶ ĂŌĞƌƚŚĞŶĚŽĨƚŚĞŽůĚtĂƌ Günter Bischof, Ferdinand Karlhofer (Eds.) CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES | VOLUME 22 UNO PRESS innsbruck university press Copyright © 2013 by University of New Orleans Press, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage nd retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to UNO Press, University of New Orleans, LA 138, 2000 Lakeshore Drive. New Orleans, LA, 70119, USA. www.unopress.org. Printed in the United States of America Design by Lauren Capone Cover photo credit: Hopi Media Published in the United States by Published and distributed in Europe University of New Orleans Press: by Innsbruck University Press ISBN: 9781608011162 ISBN: 9783902936011 UNO PRESS Contemporary Austrian Studies Sponsored by the University of New Orleans and Universität Innsbruck Editors Günter Bischof, CenterAustria, University of New Orleans Ferdinand Karlhofer, Universität Innsbruck Assistant Editor Production and Copy Editor Dominik Hofmann-Wellenhof Lauren Capone University of New Orleans Executive Editors Christina Antenhofer, Universität Innsbruck Kevin Graves, University of New Orleans Advisory Board Siegfried Beer Sándor Kurtán Universität Graz Corvinus University Budapest Peter Berger Günther Pallaver Wirtschaftsuniversität