The Occupation of Iraq

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

XVIII AIRBORNE CORPS ASSOCIATION SKY DRAGONS Spring 2012 ------82ND DOMINATES XVIII ABN CORPS NCO and SOLDIER of YEAR COMPETITION

XVIII AIRBORNE CORPS ASSOCIATION SKY DRAGONS Spring 2012 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 82ND DOMINATES XVIII ABN CORPS NCO AND SOLDIER OF YEAR COMPETITION Left to Right – CSM (Ret) Ted Gaweda, Pfc. Jeremy Shivick, Sgt. Jason Thomas, Alan Yeater On 5 April in a ceremony conducted at Sports USA, a huge sports bar at Ft. Bragg, North Carolina, two paratroopers of the XVIII Airborne Corps' 82nd Airborne Division were selected as the XVIII Airborne Corps' 2012 NCO and Soldier of the Year. They were Sgt. Jason T. Thomas, 26, and Pfc. Jeremy Shivick, 21. Both Soldiers are assigned to the 1st Platoon, C Company, 2nd Battalion, 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment, which is part of the division's 3rd Brigade Combat Team (BCT). This is 2 the first time that both winners were from the same unit. The competition was held from 2 to 4 April, and the winners were announced during the ceremony which was presided over by the Ft. Bragg Garrison Command Sergeant Major (CSM) Samuel Campbell and the command sergeant major of XVIII Abn Corps' NCO Academy, CSM Nicolino Parisi. These were four days of grueling, early morning and late night events which included basic Soldier skills, the Army physical fitness test, a written exam, urban map orienteering, M4 rifle qualification, a weapons event, and an interview board. The competition certainly challenged the confidence and motivation of the Soldiers. Twenty-one Soldiers competed, representing each subordinate unit of the XVIII Abn Corps. Spc. Michael C. Lauritzen, from Jackson, Michigan, assigned to the 716th MP Battalion, 16th MP Brigade, Ft. Campbell, Kentucky, was quoted saying, “I'm grateful for being here, glad that my leadership had the confidence in me to compete at this level. -

The Courage of General Matthew Ridgway

The Courage of General Matthew Ridgway Full Lesson Plan COMPELLING QUESTION How can acting with courage help you accomplish your identity and purpose? VIRTUE Courage DEFINITION Courage is the capacity to overcome fear in order to do good. LESSON OVERVIEW In this lesson, students will explore the life of Matthew Ridgway and his role in the Korean War. Students will understand how Matthew Ridgway’s courage helped save the United States’ and United Nations’ forces during the Korean War. Through his example, they will learn how they can use courage in their own lives to accomplish their purpose. OBJECTIVES • Students will analyze General Matthew Ridgway’s performance during the Korean War. • Students will understand how to use courage to accomplish their purpose. • Students will apply their knowledge of courage to their own lives. BACKGROUND The Korean War was an outgrowth of an unstable situation on the Korean Peninsula at the conclusion of the Second World War. In August 1945, the Soviet Union declared war on the Empire of Japan. With the endorsement of the United States, Soviet forces seized land in the northern part of the peninsula, stopping at the 38th Parallel. The United States then occupied the southern half. Two different political regimes with opposing views emerged from this situation, creating the perfect recipe for conflict. War broke out in June 1950. North Korea, hoping to assert its dominance over the entire peninsula, invaded South Korea and made quick progress. South Korea, supported by United States and United https://voicesofhistory.org BACKGROUND Nations forces, fell back around the port city of Pusan. -

Three US Joint Forces Command (USJFCOM) "Lessons Learned" Reports for the Period of the Surge of Forces in Or About 2007 for Operation Iraqi Freedom

Description of document: Three US Joint Forces Command (USJFCOM) "Lessons Learned" reports for the period of the surge of forces in or about 2007 for Operation Iraqi Freedom Requested date: 28-August-2010 Released date: 01-November-2010 Posted date: 29-November-2010 Titles of documents: Operation Iraqi Freedom, January 2007 to December 2008 - The Comprehensive Approach: an Iraq Case Study, 16 February 2010 Joint Tactical Environment: An Analysis of Urban Operations in Iraq, 2008 (undated) Operation Iraqi Freedom October to December 2007 - Counterinsurgency Targeting and Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (25 March 2008) Source of document: U.S. Joint Forces Command FOIA Requestor Service Center (J00L) 1562 Mitscher Avenue, Ste 200 Norfolk, VA 23551-2488 Fax: (757) 836-0058 The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. -

Main Command Post-Operational Detachments

C O R P O R A T I O N Main Command Post- Operational Detachments (MCP-ODs) and Division Headquarters Readiness Stephen Dalzell, Christopher M. Schnaubelt, Michael E. Linick, Timothy R. Gulden, Lisa Pelled Colabella, Susan G. Straus, James Sladden, Rebecca Jensen, Matthew Olson, Amy Grace Donohue, Jaime L. Hastings, Hilary A. Reininger, Penelope Speed For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR2615 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-1-9774-0225-7 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2019 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface This report documents research and analysis conducted as part of a project entitled Multi- Component Units and Division Headquarters Readiness sponsored by U.S. -

ARMY the Army Is Older Than the Country It Serves

Overview YOUR UNITED STATES ARMY The Army is older than the country it serves. Authorized by the Second Continental Congress, the Continental Army was established on 14 June 1775. THE ARMY: • is the oldest and largest of the military departments; • has Soldiers in every state and U.S. territory (Total Army); • is the second largest U.S. employer (Wal-Mart is the largest); • has over 250 Military Occupational Specialties and Officer specialties; and • is the foundation of the Joint Force. Fewer than 1% of Americans currently serve in the military; 79% of Soldiers come from families that have served in the military. People Are Our Army SOLDIERS SERVE AND LIVE BY A SET OF SEVEN COMMON VALUES: LOYALTY DUTY RESPECT SELFLESS SERVICE EVERY SOLDIER HONOR IS A VOLUNTEER INTEGRITY PERSONAL COURAGE Soldiers are not in the Army— Soldiers are the army. Gen. Creighton Abrams, 26th Chief of Staff of the Army America’s Army 1.012 MILLION* 340,216 SOLDIERS PIECES OF EQUIPMENT ~187,000 WORLDWIDE DEPLOYED 284,344 26,232 WHEELED COMBAT VEHICLES VEHICLES 82% 18% MALE FEMALE 20,742 4,300 MRAP AIRCRAFT VEHICLES • 55% Caucasian • 21% African American • 16% Hispanic 4,466 132 • 5% Asian/Pacific Islander STRYKER WATERCRAFT • 3% Other/Unknown VEHICLES *AS OF MAY 21 The American Soldier: Then & Now 1968 2020 (ENLISTED) (ENLISTED) • 22 years old • 28 years old • 79% high school graduates • 96% high school graduates • < 1% female • 18% female • 21% minority • 42% minority • 60% draftees • 100% volunteers • 36% married • 52% married • SGT base pay = $279/mo* • SGT base pay = $3,001/mo • SGLI coverage = $10,000* • SGLI coverage = $400,000 • 35 lbs of equipment • 75+ lbs of equipment ($1,856)* ($19,454) • Individual replacements • Unit rotations • 62% survival rate if wounded • 88% survival rate if wounded * NOT ADJUSTED FOR INFLATION What Your Army Does The U.S. -

Cultural Resource Survey of Cold War Properties Fort Bragg, North Carolina

CULTURAL RESOURCE SURVEY OF COLD WAR PROPERTIES FORT BRAGG, NORTH CAROLINA AUGUST, 2005 Report Prepared By Thomason and Associates Preservation Planners P.O. Box 121225 Nashville, TN 37212 Tel and Fax: 615-385-4960 e-mail: [email protected] Report Prepared For the US Corps of Engineers, Savannah, Georgia and the Cultural Resources Management Program, Fort Bragg, North Carolina Principal Investigator, Philip Thomason ──────────────────────── TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures....................................................................................................................................... iii Abstract ................................................................................................................................................. iv I. Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 1 II. The Cold War Context of Fort Bragg ...................................................................................... 8 III. The Cold War and National Register Eligibility ................................................................... 36 IV. Fort Bragg’s Cold War-Era National Register Eligible Properties ....................................... 48 V. Summary ................................................................................................................................. 66 VI. Bibliography .......................................................................................................................... -

"Jumping JAG", the Incredible Wartime Career of Nicholas E. Allen

" Allen was unique in at least one other as a member of the Air Force Judge Advo happened to him- lmtil an exanunation of way: Gavin previously had been so im cate General's Corps, finished his military his NARA me provided the answer. pressed withAllen's legal work that Gavin career as a brigadier general, there is no had obtained a battlefield promotion for doubt that Allen was an exceptional lawyer, 'l'DI~ "lUI. lUUlU(~llNS": him-the only time in history that an a courageous soldier, and an outstanding air 'I'HI~ U2Nn llIlUIOUNI~ nnTISION Army lawyer has received this high honor man.Allen's incredible World War II career for outstanding performance in combat. can only be told today because his military The 82nd Airborne Division has a short Allen rose from second lieutenant to lieu records have been preserved in the but distinguished history. First organized tenant colonel in just two and a half National Archives and Records Administra in 1917 as part of Gen. John ]. Pershing's years-fast even by wartime standards. tion's Military Personnel Records Center in American Expeditionary Force, the unit Allen's World War II career was singu St. Louis, Missouri. Allen died in 1993, but picked up its nickname, the "All-Ameri larly remarkable by any measure, but even because his records contain photographs, cans," from the fact that its originalmem more so because he was a lawyer, not a documents, and detailed repOlts on his per bers hailed from all 48 states. After World combat leader. formance of duty, a complete picture of his War I ended, the division was deactivated When one considers that he subse unusual military career can be assembled. -

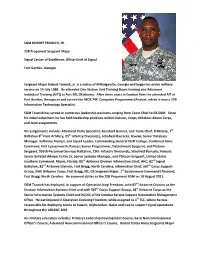

SGM ROBERT TRAWICK, JR. 25B Proponent Sergeant Major Signal

SGM ROBERT TRAWICK, JR. 25B Proponent Sergeant Major Signal Center of Excellence, Office Chief of Signal Fort Gordon, Georgia Sergeant Major Robert Trawick, Jr. is a native of Milledgeville, Georgia and began his active military service on 14 July 1988. He attended One Station Unit Training (basic training and Advanced Individual Training (AIT)) at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. After three years in Combat Arms he attended AIT at Fort Gordon, Georgia as and earned the MOS 74F, Computer Programmer/Analyst, which is now a 25B Information Technology Specialist. SGM Trawick has served in numerous leadership positions ranging from Team Chief to G6 SGM. Since his initial enlistment he has held leadership positions within Division, Corps, Echelons Above Corps, and Joint assignments. His assignments include: Advanced Party Specialist, Assistant Gunner, and Team Chief, B Battery, 7th Battalion 8th Field Artillery, 25th Infantry Division(L), Schofield Barracks, Hawaii; Senior Database Manager, Software Analyst, and Squad Leader, Commanding General Staff College, Combined Arms Command, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas; Senior Programmer, Detachment Sergeant, and Platoon Sergeant, 556th Personnel Services Battalion, 25th Infantry Division(L), Schofield Barracks, Hawaii; Senior Enlisted Advisor to the J5, Senior Systems Manager, and Platoon Sergeant, United States Southern Command, Miami, Florida; 82nd Airborne Division Information Chief, HHC, 82nd Signal Battalion, 82nd Airborne Division, Fort Bragg, North Carolina; Information Chief, 507th Corps Support Group, XVIII Airborne Corps, Fort Bragg, NC; G6 Sergeant Major, 1st Sustainment Command (Theater), Fort Bragg, North Carolina. He assumed duties as the 25B Proponent SGM on 10 August 2011. SGM Trawick has deployed, in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom, with 82nd Airborne Division as the Division Information Systems Chief and with 507th Corps Support Group, 18th Airborne Corps as the Senior Information Systems Chief and NCOIC of the Combat Service Support Automation Management Office. -

Wear and Appearance of Army Uniforms and Insignia

Army Regulation 670–1 Uniform and Insignia Wear and Appearance of Army Uniforms and Insignia Headquarters Department of the Army Washington, DC 31 March 2014 UNCLASSIFIED SUMMARY of CHANGE AR 670–1 Wear and Appearance of Army Uniforms and Insignia This major revision, dated 31 March 2014-- o Notifies Soldiers of which portions of the regulation are punitive and violations of these provisions may subject offenders to adverse administrative action and/or charges under the provisions of the Uniform Code of Military Justice (paras 1-5a, 3-2, 3-3, 3-4, 3-5, 3-7, and 3-10). o Removes Army Ideas for Excellence Program (para 1-6a). o Updates Responsibilities for The Institute of Heraldry (para 2-3), Program Executive Officer, Program Executive Office Soldier, and U.S. Army Natick Soldier Research, Development and Engineering Center (para 2-4). o Updates the hair and fingernail standards and grooming policies for males and females (para 3-2). o Updates tattoo and brand policy (para 3-3). o Updates jewelry policy to limit gauging size to 1.6mm (para 3-4(d)) and adding prohibited dental ornamentation (para 3-4f). o Updates policy of the wear of Army uniforms at national, regional, and local events (para 3-5). o Updates policy on use of electronic devices while in uniform (para 3-6). o Updates policy on wear of combat uniform on commercial flights (para 3-7c). o Updates policy on hand carried and shoulder bags (3-7f). o Updates policy on eyeglasses, sunglasses, and contact lenses (para 3-10). o Updates the policy on wear of identification tags (para 3-11a). -

Army in Desert St Rm

ARMY I IN DESERT ST RM ASSOCIATIO THE UNITED STATES WILSON BOULEVARD • ARLINGTON, It PREPARED UNDER THE AUSPICES OF THE AUSA INSTITUTE OF LAND WARFARE ASSOCIATION OF THE UNITED STATES ARMY 2425 WILSON BOULEVARD ARLINGTON, VIRGINIA 22201-3385 A Nonprofit, Educational Association Reproduction of this Report, in whole or in part, is authorized with appropriate acknowledgment of the source. II THE U.S. ARMY IN OPERATION DESERT STORM An Overview Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 1 A GULF WAR CHRONOLOGY . ....... ..... ....................................................................... 2 HOW IT STARTED ............................................ ........................................................... 3 OPERATION DESERT SHIELD ........ ......................................... .......... ....... ................ 5 Army Deployment - Phase !. ... ........................... ........................................................ 7 Army Deployment - Phase!! . .............................................. ... ................................... 8 A Logistics Miracle................................................................................................... 9 The Reserve Components in the Gulf War.............................................................. 10 Countdown to War.................................................................................................. 11 OPERATION DESERT STORM............................................................................... -

Questionnaire for Presidential Appointees

~-- - -- -------- ----- ;. SELECT COMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE UNITED STATES SENATE QUESTIONNAIRE FOR COMPLETION BY PRESIDENTIAL NOMINEES SELECf COMMITIEE ON INTELLIGENCE UNITED STATES SENATE QUESTIONNAIRE FQR COMPLETION BY PRESIDENTIAL NOMINEES PART A - BIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION I. NAME: David H. Petraeus 2. DATE AND PLACE OF BIRTH: 7 November 1952, Cornwall, NY 3. MARITAL STATUS: Married 4. SPOUSE' S NAME: Ho ll ister K.. Petraeus 5. SPOUSE'S MAlDEN NAME IF APPUCABLE: Knowllon 6. NAMES AND AGES OF CHILDREN: [INFORMATI ON REDACTED] 7. EDUCATION SINCE HIGH SCHOOL: INSTInmON DATES AITENPEP pEGREE RECEIVEP DATE Of DEGREE United States Military Academy Jun 70- Jun 74 as, No Major Jun 1974 Princeton University Jun 83 -Jun 85 MPA, Inti Relations Jun 1985 Princeton University Offcampus PHD, Inti Relations Jun 1987 8. EMPLOYMENT RECORD (LIST ALL POSITIONS HELD SINCE COLLEGE, JNCLUDING MJLlTARY SERVICE. INDICATE NAME OF EMPLOYER, POSITION, TITLE OR DESCRIPTION, LOCATION, AND DATES OF EMPLOYMENT.) EMPLOYER pQSmONlI1TLE LOCATION United States Army Platoon LeaderlPlaos Officer Viccnza, Italy =May 7S - Jan 79 Battalion Adjutantll LT United States Army Asst. Operations Officer/CPT Fort Stewart, GA Jan 79 - lui 79 United States Army Company Commander/CPT Fort Stewart, GA Ju179-May81 and Battalion Operations Officer United States Army Aide to !he Division Commander/CPT Fort Stewart, GA May 81 - May 82 United States Army Student CGSClCPT Fort Leavenworth, KS May 82 - Jim 8) United States Army Student, Princeton University Princeton, NJ Jun 8) - Jim 85 United -

The Courage of General Matthew Ridgway

The Courage of General Matthew Ridgway Handout A: Narrative BACKGROUND The Korean War was an outgrowth of an unstable situation on the Korean Peninsula at the conclusion of the Second World War. In August 1945, the Soviet Union declared war on the Empire of Japan. With the endorsement of the United States, Soviet forces seized land in the northern part of the peninsula, stopping at the 38th Parallel. The United States then occupied the southern half. Two different political regimes with opposing views emerged from this situation, creating the perfect recipe for conflict. War broke out in June 1950. North Korea, hoping to assert its dominance over the entire peninsula, invaded South Korea and made quick progress. South Korea, supported by United States and United Nations forces, fell back around the port city of Pusan. They fought hard and were finally relieved when U.N. and U.S. forces landed at Incheon, forcing the North Koreans to withdraw. The fight then moved north, all the way to the Chinese border. Then, in November, the Chinese shocked the world by allying with North Korea and attacking U.N. and U.S. forces, once again driving them south. Fighting eventually settled in the area around the 38th Parallel. It was during this chaotic situation that General Matthew Ridgway arrived on the Korean Peninsula. NARRATIVE Matthew Ridgway was born into a military family in March 1895. His father, Colonel Thomas Ridgway, was an artillery officer. Upon graduating high school, Ridgway applied for the United States Military Academy, West Point. However, he failed the entrance exam.