Trick Or Treat Rev02.3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nov 2 5 2009

U.S. Department of Homeland Security U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services Ofice ofAdministrative Appeals, MS 2090 Washington, DC 20529-2090 U. S. Citizenship and Immigration NOV 2 5 2009 IN RE: PETITION: Immigrant Petition for Alien Worker as an Alien of Extraordinary Ability Pursuant to Section 203(b)(l)(A) of the Immigration and Nationality Act, 8 U.S.C. 5 1153(b)(l)(A) ON BEHALF OF PETITIONER: INSTRUCTIONS: This is the decision of the Administrative Appeals Office in your case. All documents have been returned to the office that originally decided your case. Any further inquiry must be made to that office. If you believe the law was inappropriately applied or you have additional information that you wish to have considered, you may file a motion to reconsider or a motion to reopen. Please refer to 8 C.F.R. 5 103.5 for the specific requirements. All motions must be submitted to the office that originally decided your case by filing a Form I-290B, Notice of Appeal or Motion, with a fee of $585. Any motion must be filed within 30 days of the decision that the motion seeks to reconsider or reopen, as required by 8 C.F.R. 8 103.5(a)(l)(i). Perry Rhew Chief, Administrative Appeals Office DISCUSSION: The Director, Texas Service Center, initially approved the preference visa petition. Subsequently, the director issued a notice of intent to revoke the approval of the petition (NOIR). In a Notice of Revocation (NOR), the director ultimately revoked the approval of the Immigrant Petition for Alien Worker (Form 1-140). -

Careers Matter May 2015 Changed.Indd

10 Careers Matter, supplement to the Mail & Guardian May 29 to June 4 2015 Helpful contacts General enquiries: [email protected] Johannesburg: Tel 011 327 2002 Durban North: Tel 031 573 2038 King Sabata Dalindyebo FET College Cape Town Campus: PO Box 3423, Fax 086 409 1627 [email protected] Fax: 031 563 2268 (Mthatha) Cape Town 8000 Fax 021 422 1827 Pretoria: Tel 012 346 2189 Fax 086 409 1627 [email protected] Tel 047 505 1000 Fax 047 536 0932 Johannesburg Campus: PO Box 2289, [email protected] www.inscape.co.za Durban West: Tel 031 266 8400 [email protected] Parklands 2121 Fax 011 781 2796 Fax 031 266 9009 Engcobo Campus: Tel 047 548 1467 Intec College (Distance Learning) [email protected] Libode Ntshuba Campus: Tel 083 477 6972 AFDA Film, TV and Performance School Tel 021 417 6700 Fax 021 419 1210 Midrand: Tel 010 224 4300 Mapuzi Campus: Tel 047 575 9044 Cape Town: Tel 021 448 7500 www.intec.edu.za Fax 086 6126058 Mngazi Campus: Tel 047 576 9469 Fax 021 448 7610 [email protected] [email protected] Mthatha Campus: Tel 047 5360 923 Durban: Tel 031 569 2252 / 2317 Leaders in the Science of Fashion (Lisof) Pietermaritzburg: Tel 033 386 2376 Ntabozuko Campus: Tel 047 575 9044 [email protected] Johannesburg: Fax 033 386 3700 www.ksdfetcollege.co.za Johannesburg: Tel 011 482 8345 Tel 086 11 54763 Fax 011 326 1767 [email protected] Fax 011 482 8347 Pretoria: Tel 012 362 6827 Port Elizabeth: PO Box 27436, Lovedale FET College [email protected] Fax 086 695 1843 Greenacres 6057 (King William’s -

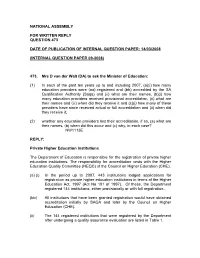

14/03/2008 (Internal Question P

NATIONAL ASSEMBLY FOR WRITTEN REPLY QUESTION 473 DATE OF PUBLICATION OF INTERNAL QUESTION PAPER: 14/03/2008 (INTERNAL QUESTION PAPER 09-2008) 473. Mrs D van der Walt (DA) to ask the Minister of Education: (1) In each of the past ten years up to and including 2007, (a)(i) how many education providers were (aa) registered and (bb) accredited by the SA Qualification Authority (Saqa) and (ii) what are their names, (b)(i) how many education providers received provisional accreditation, (ii) what are their names and (iii) when did they receive it and (c)(i) how many of these providers have since received actual or full accreditation and (ii) when did they receive it; (2) whether any education providers lost their accreditation, if so, (a) what are their names, (b) when did this occur and (c) why, in each case? NW1113E REPLY: Private Higher Education Institutions The Department of Education is responsible for the registration of private higher education institutions. The responsibility for accreditation vests with the Higher Education Quality Committee (HEQC) of the Council on Higher Education (CHE). (a) (i) In the period up to 2007, 443 institutions lodged applications for registration as private higher education institutions in terms of the Higher Education Act, 1997 (Act No 101 of 1997). Of these, the Department registered 144 institutions, either provisionally or with full registration.. (bb) All institutions that have been granted registration would have obtained accreditation initially by SAQA and later by the Council on Higher Education (CHE). (ii) The 144 registered institutions that were registered by the Department after undergoing a quality assurance evaluation are listed in Table 1. -

Register of Private Higher Education Institutions

REGISTER OF PRIVATE HIGHER EDUCATION INSTITUTIONS LAST UPDATE 22 MAY 2019 This register of private higher education institutions (hereafter referred to as the Register) is published in accordance with section 54(2)(a)(i) of the Higher Education Act, 1997 (Act No. 101 of 1997) (hereafter referred to as the Act). In terms of section 56(1) (a), any member of the public has the right to inspect the register. IMPORTANT NOTE FOR THE MEDIA The Department of Higher Education and Training recognizes that the information contained in the Register is of public interest and that the media may wish to publish it. In order to avoid misrepresentation in the public domain, the Department of Higher Education and Training kindly requests that all published lists of registered institutions are accompanied by the relevant explanatory information, and include the registered qualifications of each institution. The Register is available for inspection at:http://www.dhet.gov.za: Look under Documents/Registers ‐2 ‐ INTRODUCTION The Register provides the public with information on the registration status of private higher education institutions. Section 54(2)(a)(i) of the Act requires that the Registrar of Private Higher Education Institutions (hereafter referred to as the Registrar) enters the name of the institution in the Register, once an institution is registered. Section 56(1)(b) grants the public the right to view the auditor’s report as issued to the Registrar in terms of section 57(2)(b) of the Act. Copies of registration certificates must be kept as part of the Register, in accordance with Regulation 20. -

Rhodes University Research Report 2006 Contents

RHODES UNIVERSITY RESEARCH REPORT 2006 CONTENTS PREFACE 3 INTRODUCTION 4 RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS 6 ACADEMIC DEVELOPMENT CENTRE 8 ACCOUNTING 10 ANTHROPOLOGY 12 BIOCHEMISTRY MICROBIOLOGY AND BIOTECHNOLOGY 16 BOTANY 25 CHEMISTRY 34 COMPUTER SCIENCE 42 DICTIONARY UNIT 49 DRAMA 50 ECONOMICS AND ECONOMIC HISTORY 57 EDUCATION 61 EMUNIT 71 ENGLISH 72 ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LINGUISTICS 75 ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE 79 FINE ART 83 GEOGRAPHY 86 GEOLOGY 90 HISTORY 94 HUMAN KINETICS AND ERGONOMICS 97 ICHTHYOLOGY AND FISHERIES SCIENCE 102 INFORMATION SYSTEMS 108 INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF ENGLISH IN AFRICA 111 INSTITUTE FOR WATER RESEARCH 116 INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC RESEARCH 119 INTERNATIONAL LIBRARY OF AFRICAN MUSIC 123 INVESTEC BUSINESS SCHOOL 124 JOURNALISM AND MEDIA STUDIES 126 LAW 132 LIBRARY 138 MANAGEMENT 139 MATHEMATICS (PURE AND APPLIED) 142 MUSIC AND MUSICOLOGY 144 PHARMACY 148 PHILOSOPHY 159 PHYSICS AND ELECTRONICS 163 POLITICAL AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES 168 PSYCHOLOGY 173 RUMEP 178 SCHOOL OF LANGUAGES 179 SOCIOLOGY AND INDUSTRIAL SOCIOLOGY 181 STATISTICS 186 ZOOLOGY AND ENTOMOLOGY 189 2 PREFACE Rhodes University defines as one of its three core activities the production of knowledge through stimulating imaginative and rigorous research of all kinds (fundamental, applied, policy-oriented, etc.), and in all disciplines and fields. Though a small university with less than 6 000 students, the student profile and research output (publications, Master’s and Doctoral graduates) of Rhodes ensures that it occupies a distinctive place in the overall South African higher education landscape. For one, almost 25% of Rhodes’ students are postgraduates. Coming from a diversity of countries, these postgraduates ensure that Rhodes is a cosmopolitan and fertile environment of thinking and ideas. -

Register of Private Higher Education Institutions

REGISTER OF PRIVATE HIGHER EDUCATION INSTITUTIONS LAST UPDATE 24 FEBRUARY 2014 This register of private higher education institutions is published in accordance with section 54(2)(a)(i) of the Higher Education Act, 1997 (Act No. 101 of 1997). In terms of section 56(1) (a), any member of the public has the right to inspect the register. IMPORTANT NOTE FOR THE MEDIA The Department of Higher Education and Training recognizes that the information contained in the register is of public interest and that the media may wish to publish it. In order to avoid misrepresentation in the public domain, the Department of Higher Education and Training kindly requests that all published lists of registered institutions are accompanied by the relevant explanatory information, and include the registered qualifications of each institution. The register is available for inspection at: http://www.dhet.gov.za INTRODUCTION The Register of Private Higher Education Institutions (hereafter referred to as the Register) provides the public with information on the registration status of private higher education institutions. Section 54(2)(a)(i) of the Act requires that the Registrar of Private Higher Education Institutions (hereafter referred to as the Registrar) enters the name of the institution in the Register, once an institution is registered. Section 56(1)(b) grants the public the right to view the auditor’s report as issued to the Registrar in terms of section 57(2)(b) of the Act. Copies of registration certificates must be kept as part of the Register, in accordance with Regulation 20. ‐ 2 ‐ The Legal Framework In terms of the National Qualifications Framework Act, 2008 (Act. -

Gcro Data Brief: No

DATA BRIEF GCRO DATA BRIEF: NO. 4 Transformation of Higher Education for Development in the Gauteng City-Region (GCR) March 2013 Produced by the Gauteng City-Region Observatory (GCRO) A partnership of the University of Johannesburg (UJ), University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg (Wits), the Gauteng Provincial Government (GPG) and organized local government Annsilla Nyar GCRO Data Brief No. 4 Transformation of Higher Education for Development in the Gauteng City-Region (GCR) Contents 1. Introduction ....................................................................................... 3 2. Higher education provision in the GCR.................................4 3. Producing the graduates needed for social and economic development ...............................................................6 3.1 Enrolments by GCR HEIs ..........................................................................................6 3.2 Fields of study by GCR HEIs ..................................................................................8 3.3 Graduate output and growth, 2000-2010 .......................................................9 4. Achieving equity in the higher education system ......... 10 4.1 Student Enrolment by race and sex – 1995-2010 ........................................ 10 5. Staff Equity .........................................................................................11 5.1 Staff by personnel category for all HEIs in GCR, 2010 .............................11 5.2 Staff by qualification levels ....................................................................................12 -

Register of Private Higher Education Institutions

DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION REGISTER OF PRIVATE HIGHER EDUCATION INSTITUTIONS LAST UPDATE 11 DECEMBER 2009 This register of private higher education institutions is published in accordance with section 54(2)(a)(i) of the Higher Education Act, 1997 (Act No. 101 of 1997). In terms of section 56(1)(a), any member of the public has the right to inspect the register. IMPORTANT NOTE FOR THE MEDIA The Department of Education recognises that the information contained in the register is of public interest and that the media may wish to publish it. In order to avoid misrepresentation in the public domain, the Department of Education kindly requests that all published lists of registered institutions are accompanied by the relevant explanatory information, and include the registered qualifications of each institution. The register is available for inspection at: http://www.education.gov.za and look under DoE Branches/Higher Education/Private Higher Education Institutions/Directorate Documents/Register of Private Higher Education Institutions INTRODUCTION The Register of Private Higher Education Institutions (hereafter referred to as the Register) provides the public with information on the registration status of private higher education institutions. Section 54(2)(a)(i) of the Act requires that the Registrar of Private Higher Education Institutions (hereafter referred to as the Registrar) enters the name of the institution in the Register, once an institution is -2- registered. Section 56(1)(b) grants the public the right to view the auditor’s report as issued to the Registrar in terms of section 57(2)(b) of the Act. Copies of registration certificates must be kept as part of the Register, in accordance with Regulation 20. -

Board Notice 76 of 2015

Reproduced by Sabinet Online in terms of Government Printer’s Copyright Authority No. 10505 dated 02 February 1998 STAATSKOERANT, 31 MAART 2015 No. 38665 3 BOARD NOTICES BOARD NOTICE 76 OF 2015 FINANCIAL SERVICES BOARD FINANCIAL ADVISORY AND INTERMEDIARY SERVICES ACT, 2002 (ACT NO 37 OF 2002) ENDMENT NOTICE ON THE DETERMINATION OF QUALIFYING CRITERIA AND QUALIFICATIONS FOR FINANCIAL SERVICES PROVIDERS, 2014 I, Caroline Dey da Silva, the Deputy Registrar of Financial Services Providers, hereby under Part V of the Determination of Fit and Proper Requirements for Financial Services Providers, 2008, amend Annexure 2 to the Notice on the Determination of Qualifying Criteria and Qualifications for Financial Services Providers, Number 1 of 2008, as set out in the Schedule to this Notice. This Notice is called the Amendment Notice on the Determination of Qualifying Criteria and Qualifications for Financial Services Providers, 2015. CD da Silva, Deputy Registrar of Financial Services Providers SCHEDULE AMENDMENTS NOTICE ON THE DETERMINATION OF QUALIFYING CRITERIA AND QUALIFICATIONS FOR FINANCIAL SERVICES PROVIDERS, 2015 Definition 1. In this Schedule "the Notice" means the Notice on the Determination of Qualifying Criteria and Qualifications for Financial Services Providers, Number 1 of 2008, as published by Board Notice 105 of 2008 in Government Gazette No. 31514 of 15 October 2008. Amendment of Annexure 2 to the Notice 2. Annexure 2 of the Schedule to the Notice is hereby amended by the substitution for the lists of recognised qualifications of the following lists: This gazette is also available free online at www.gpwonline.co.za Reproduced by Sabinet Online in terms of Government Printer’s Copyright Authority No. -

Title Initial Surname Qualification Mr G Abrahams Masters Degree Mrs JM

Title Initial Surname Qualification Mr G Abrahams Masters Degree Mrs JM Abrahams Degree/ Bachelor’s Degree Ms W Abrahams Masters Degree Mr CJ Abrahams Bachelor Honours Degree Mr E Adam Masters Degree Mr MHA Adam Bachelor Honours Degree Mr MHA Adam Bachelor Honours Degree Ms OS Adu Postgraduate Diploma Ms KR Aires Bachelor Honours Degree Miss H Akoon Degree/ Bachelor’s Degree Mr F Ali Bachelor Honours Degree Ms PK Allison Masters Degree Mrs Z Ally Bachelor Honours Degree Mrs Z Ally Bachelor Honours Degree Mr PE Alvarez Masters Degree Dr F Amoah Doctoral Degree Mrs RG Amod Masters Degree (Professional) Mrs CJ Anderson Bachelor Honours Degree Mrs FS Anderson Bachelor Honours Degree Mrs PL Andrew Bachelor Honours Degree Mrs C Andrews Masters Degree Mrs T Anirudh Masters Degree Mrs JJ Apostolis Masters Degree Mrs JS Appalsami Masters Degree Mr M Appalsami Postgraduate Diploma Mrs A Archer Bachelor Honours Degree Mrs G Archibald Postgraduate Diploma Mr A Arendse Bachelor Honours Degree Mrs CB Arendse Bachelor Honours Degree Mrs CB Arendse Postgraduate Diploma Mrs BA Arentsen Degree/ Bachelor’s Degree Mrs AHJ Armatas Postgraduate Diploma Ms ZMM Arthur Bachelor Honours Degree Dr A Asakitikpi Doctoral Degree Ms H Ashington Masters Degree Mrs K Atterbury Degree/ Bachelor’s Degree Miss LK Attwood-Smith Bachelor Honours Degree Ms M Augeal Bachelor Honours Degree Ms NJ Ausmeier Masters Degree Mr N E Avery Masters Degree Miss PM Avgenikos Degree/ Bachelor’s Degree Mr MA Ayami Bachelor Honours Degree Mrs BM Ayliffe Postgraduate Certificate of Education -

Private Higher Education Institutions

REGISTER OF PRIVATE HIGHER EDUCATION INSTITUTIONS LAST UPDATE 22 MARCH 2017 This register of private higher education institutions (hereafter referred to as the Register) is published in accordance with section 54(2)(a)(i) of the Higher Education Act, 1997 (Act No. 101 of 1997) (hereafter referred to as the Act). In terms of section 56(1) (a), any member of the public has the right to inspect the register. IMPORTANT NOTE FOR THE MEDIA The Department of Higher Education and Training recognizes that the information contained in the Register is of public interest and that the media may wish to publish it. In order to avoid misrepresentation in the public domain, the Department of Higher Education and Training kindly requests that all published lists of registered institutions are accompanied by the relevant explanatory information, and include the registered qualifications of each institution. The Register is available for inspection at:http://www.dhet.gov.za: Look under Documents/Registers INTRODUCTION The Register provides the public with information on the registration status of private higher education institutions. Section 54(2)(a)(i) of the Act requires that the Registrar of Private Higher Education Institutions (hereafter referred to as the Registrar) enters the name of the institution in the Register, once an - 2 - institution is registered. Section 56(1)(b) grants the public the right to view the auditor’s report as issued to the Registrar in terms of section 57(2)(b) of the Act. Copies of registration certificates must be kept as part of the Register, in accordance with Regulation 20. -

Inkanyiso Vol 3 FM.Fm

Inkanyiso Journal of Humanities and Social Science Volume 3 2011 Contents & Index of Authors NUMBER INDEX No. 1 ................................... 1– 90 No. 2 ...............................91 – 164 Supplement to Inkanyiso Vol. 3, No. 2, 2011 Inkanyiso Journal of Humanities and Social Science ISSN 2077-2815 Volume 3 Number 2, 2011 Editor-in-Chief Prof. Dennis N. Ocholla Department of Information Studies University of Zululand [email protected] Editors Prof. C. Addison, Prof. M. Hooper, Dr. E.M. Mncwango, Prof. C.T. Moyo and Prof. E.M. Mpepo Editorial Advisory Board Prof. Catherine Addison, Associate Professor, Department of English, University of Zululand, South Africa - [email protected] Prof. Sandra Braman, Professor, Department of Communication, University of Wisconsin Milwaukee - [email protected] Prof. Hannes Britz, Professor and Interim Provost/Vice Chancellor, University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, USA – [email protected] Prof. Stephen Edwards, Durban, South Africa - [email protected] Dr. Gillian Gane, University of Massachusetts, Boston, USA- [email protected] Prof. Myrtle Hooper, Professor and Head of the Department of English, University of Zululand, South Africa – [email protected] Prof. Mojalefa LJ Koenane, Senior Lecturer, Department of Philosophy and Systematic Theology, University of South Africa - [email protected] Prof. Nomahlubi Makunga, Executive Dean Faculty of Arts, University of Zululand, South Africa – [email protected] Prof. Nicholas Meihuizen, Professor, Department of English, North West University Potchestrum Campus, South Africa - [email protected] Dr. Elliot Mcwango, Senior Lecturer, Department of General Linguistics, University of Zululand, South Africa - [email protected] Prof. Themba Moyo, Professor and Head of the Department of General Linguistics, University of Zululand, South Africa - [email protected] Prof.