Higher Education Monitor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sumbandila Scholarship Trust

The Sumbandila Scholarship Trust Transforming the lives of underprivileged children, creating entrepreneurs and leaders who will make significant contributions to the future of South Africa. We believe that the eight year relationship we have with the students starts a process of positive change that lives with the children throughout their lives and influences the people and communities with whom they interact. Table of Contents Introduction ....................................................................... Page 1 Education is the key .......................................................... Page 2 The story so far.................................................................. Page 3 Sumbandila Our Programmes............................................................... Page 4 means Student selection............................................................... Page 5 ‘show the way’, or directly The Full Residential Programme .......................................Page 6 translated Schooling at Ridgeway College ........................................Page 7 from Venda, The Outlier Programme .....................................................Page 8 ‘point the road’. Tertiary Education .............................................................. Page 9 Student numbers ............................................................. Page 11 Our impact so far ............................................................ Page 12 Academic performance ................................................... Page 12 Building communities -

February 2013 Teacher.Co.Za Reducing Disciplinary Challenges a System That Works

Thanking Educators School your do parent no drop off teacher learners zone Page 13 Page 16 Page 17 Your Guide to Education •February 2013 teacher.co.za Reducing disciplinary challenges A system that works PBIS schools equip learners with pro-social behavioural skills. Kutlwano Khumalo is in Grade 3 at Vuleka School, the first PBIS school. Page 20. Photo: Oupa Nkosi 2 Career February 2013 theTeacher Helping in her blood Driving for people with physical disabilities Thabo Mohlala aroline Rule works as an occupational therapist and a driving consultant for people with disabili- ties such as a spinal cord Cinjury and amputations. After assessing their remaining functionality and how best they can use it, she recommends driving adap- tations that would enable them to be behind the steering wheel safely and independently, as well as how they will get their wheelchairs in and out of the car. She then refers them to the relevant companies that can build the adaptations and in an ongoing way, she works with these companies to brainstorm even more effective solutions. Where a person has had a stroke or head injury, they undergo a physical and cognitive assessment and then team up with a driving instructor to do an on-road driving test to assess whether it will be safe for the person to drive. Rule also helps manage the Driving Ambitions driving school, owned by the QuadPara association. They have two adapted vehicles that they use to Caroline Rule is passionate about the mobility of the physically disabled. Photo: Delwyn Verasamy teach people with disabilities to drive. -

A Report on the Mapping Study of Peace & Security Engagement In

A Report on the Mapping Study of Peace & Security Engagement in African Tertiary Institutions Written by Funmi E. Vogt This project was funded through the support of the Carnegie Corporation About the African Leadership Centre In July 2008, King’s College London through the Conflict, Security and Development group (CSDG), established the African Leadership Centre (ALC). In June 2010, the ALC was officially launched in Nairobi, Kenya, as a joint initiative of King’s College London and the University of Nairobi. The ALC aims to build the next generation of scholars and analysts on peace, security and development. The idea of an African Leadership Centre was conceived to generate innovative ways to address some of the challenges faced on the African continent, by a new generation of “home‐grown” talent. The ALC provides mentoring to the next generation of African leaders and facilitates their participation in national, regional and international efforts to achieve transformative change in Africa, and is guided by the following principles: a) To foster African‐led ideas and processes of change b) To encourage diversity in terms of gender, region, class and beliefs c) To provide the right environment for independent thinking d) Recognition of youth agency e) Pursuit of excellence f) Integrity The African Leadership Centre mentors young Africans with the potential to lead innovative change in their communities, countries and across the continent. The Centre links academia and the real world of policy and practice, and aims to build a network of people who are committed to the issue of Peace and Security on the continent of Africa. -

Key Indicators of Student Success at a Tertiary Institution: a Case Study of Cti Education Group’S Accounting Programmes

KEY INDICATORS OF STUDENT SUCCESS AT A TERTIARY INSTITUTION: A CASE STUDY OF CTI EDUCATION GROUP’S ACCOUNTING PROGRAMMES Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Technology: Public Management in the Faculty of Management Sciences at Durban University of Technology Ntemo Kiamuangana Maurice Student Number: 21451943 Supervisor: Dr Alexander Dawid Van Der Merwe Date: March 2015 DECLARATION I Kiamuangana Maurice Ntemo declare that (i) The research reported in this dissertation/thesis, except where otherwise indicated, is my original research. (ii) This dissertation/thesis has not been submitted for any degree or examination at any other university. (iii) This dissertation/thesis does not contain other persons’ data, pictures, graphs or other information, unless specifically acknowledged as being sourced from other persons. (iv) This dissertation/thesis does not contain other persons’ writing, unless specifically acknowledged as being sourced from other researchers. Where other written sources have been quoted, then: a) their words have been re-written but the general information attributed to them has been referenced; b) where their exact words have been used; their writing has been placed inside quotation marks, and referenced. (v) This dissertation/thesis does not contain text, graphs or tables copied and pasted from the internet, unless specifically acknowledged, and the source being detailed in the dissertation/thesis and in the references sections. Signature: i ABSTRACT Linking access with success in South African higher education has become vital. There is a clear necessity to identify and rigorously research factors contributing to student success that are within the institutions sphere of influence so that institutional policies and practices can be intentionally aligned and designed to create conducive conditions for student success This study documents the key indicators of student success based on a sample of BComm Accounting students enrolled at CTI Education group (MGI)/Durban Campus from 2009 to 2011. -

Curriculum Vitae Dr Walter Matli

CURRICULUM VITAE OF DR WALTER MATLI ____________________________________________________ PERSONAL INFORMATION Full names and Surname : Walter Matli Date of Birth : 27 October 1986 Contact Number : 076 288 3345 Email : [email protected] Nationality : South African Residential area : Tembisa Township EDUCATIONAL HISTORY 1. Institute Attended : University of South Africa (UNISA) Qualification : PhD studies (2017 to 2019) About the study: Developing an information services system framework towards developing the capacity of people who are not in employment, education or training (NEET). 2. Institute Attended : University of Johannesburg (UJ) Course : Information System Auditing Qualification : Postgraduate Diploma (2015 – 2016) 3. Institute Attended : National Institute of Teachers Technical Training & Research (Chennai, INDIA) Course : Technical Education to meet Global needs Qualification : Advanced Certificate (8 week course) 4. Institute Attended : Vaal University of Technology Course : Masters in Information Technology About the study: The use of messaging service applications as an educational supporting tool in higher education institutions (HEIs) (Completion 2015) 5. Institute Attended : University of the Free State Course : Advanced Diploma in Qualification : Higher Education2012 – 2013 6. Institute Attend : Vaal University of Technology Course : B Tech: Degree (CUM LAUDE ) Qualification : Information Technology: Business (2007 – 2011) ADDITIONAL ACTIVITIES • Member of the panel adjudicating the prestigious South African Innovation Awards hosted by My World of Tomorrow (MWOT) under Business Connexion. • Business Unity SA anti-corruption training and mentorship programme AWARDS • Rectorate’s award for teaching excellence – highest recognition - This awards are for recognizing the teaching excellence (VUT) • Vice-chancellors academic excellence award – faculty of applied and computer sciences. - This award is given to a student that obtained the highest average in the respective faculty (VUT) ORGANIZATIONAL INVOLVEMENT Current: 1. -

FADA Annual Report 2012

Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 1 OPERATING CONTEXT 7 1.1 Nature and scope of the Faculty 7 1.2 Strategic objectives 8 1.3 Governance and quality management 9 1.4 Risk management 15 1.5 Branding and marketing 16 2 TEACHING AND LEARNING 19 2.1 Enrolment figures 19 2.2 Student profile 22 2.3 Performance overview 24 2.4 Student awards and achievements 27 2.5 Teaching and learning interventions 32 2.6 Programme and module developments 38 2.7 New progammes planned for 2011-2013 42 2.8 Student experience 43 2.9 Report Teaching and Learning Forum 44 3 RESEARCH AND CREATIVE PRODUCTION 49 3.1 Performance overview 49 3.2 Research funding 62 3.3 Report: FADA Research Centre (VIAD) 66 3.4 Report: FADA Gallery 67 3.5 Report: Design for Social Development 69 3.6 Research capacity building 70 4 COMMUNITY SERVICE AND STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT 72 4.1 Community projects 72 4.2 Service to academic and professional communities 78 4.3 Public lectures, presentations and media interviews 88 4.3 New agreements and partnerships 89 4.4 Advisory committees 90 4.5 Interaction and collaboration 90 5 RESOURCE MANAGEMENT 102 5.1 Employee profile 102 5.2 Staff achievements 106 5.3 Staff developments 107 5.4 Health and Safety 113 5.5 Working environment 114 5.6 Financial Report 115 5.7 Studios, laboratories and equipment 117 5.8 Social responsibility and environmental sustainability 117 6 CONCLUSION 118 6.1 Review 118 6.2 Planning for 2013 121 APPENDICES 123 1 Departmental reviews 123 2 Departmental comments on quality management 139 3 Undergraduate and postgraduate external -

Gavin John Dollman

21 Horeb Street Gavin John Dollman LaRola Clarens, Free State Gender: Male South Africa Health: Excellent [email protected] Nationality: South African Home +2783 234 1299 Date of Birth: 1983/05/27 Office (058) 718 5234 Notice period: 60 days https://www.linkedin.com/in/gavin -dollman-17410388/ _______________________________________________________________________________ Motivation My philosophy for teaching is to provide practical industry related problems that students need to solve using hard and soft skills. Personally, I am interested in machine learning and it’s many applications within other fields. My current project involves the creation of a predictive model that prospects for fossils within South Africa using drones and image classification. This project involves machine learning, deep learning and photogrammetry to construct these predictive models. Work Experience 2015 - Present University of the Free State Lecturer, Computer Science and Informatics My role is the administration and presentation of a number of courses within the computer science field. As an academic my responsibilities do not end in the classroom, I am expected to be a researcher and actively participate in department activities such as marketing and mentorship programs. • Lectured various courses including Website Design, Databases I and II, Software Engineering, Design Patterns, Human-Computer Interaction and Data Structures (Advanced Programming) • Assessed and designed assignments, exams, project and practical’s • Designed and implemented coursework -

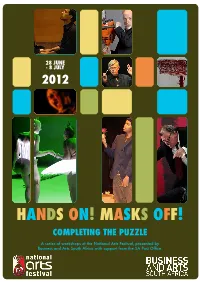

Hands On! Masks Off!

28 JUNE - 8 JULY 2012 HANDS ON! MASKS OFF! COMPLETING THE PUZZLE A series of workshops at the National Arts Festival, presented by Business and Arts South Africa with support from the SA Post Office. Growing the art of partnerships Seed to strength to sustainability Corporate Members: ABSA KWV Telkom SA Ltd Adele Lucas Promotions KykNet Terraplane Africa Empowered Le Canard Restaurant The Brand Leadership Group Anglo American Leaders Unlimited The Cement and Concrete Institute Anglogold Ashanti Legacy Group Holdings The Forum Artinsure Lemnis Lighting Africa The Grand Daddy Hotel Atterbury Live Wire Learning (Pty) Ltd The Sharks (Pty) Ltd ATKV Lombard Insurance Company Ltd The Soweto Hotel on Freedom Square Avalon Group Lotsha Ministries Trust The Walt Disney Company Africa Bell Dewar Louis Karol Architecture & Interiors TIXSA BHP Billiton Mastrantonio Holdings Total Exposure Black Coffee Design CC Matchboxology Translate.org.za Black Brand, Strategy and Design (Pty) Ltd Matumi Corporate Advisors (Pty) Ltd Transnet Foundation BMI Sponsorwatch (Pty) Ltd Mandela Bay Development Agency Trainiac SA (Pty) Ltd Boston Media House MayFord Seeds 3 Millar Warehouse CC Breinstorm Brand Architects Media 24 Ltd Vega the Brand Communication School Brown Spice Boutique CC Mercedes-Benz SA (Pty)Ltd, Vodacom Buz Publicity formerly Daimler Chrysler VWV Productions (Pty) Ltd Cape Town Partnership Middel & Partners Wag the Dog Publishers (Pty) Ltd Cell C Mobile Telephone Networks (MTN) Webber Wentzel Citadel, Private Client Wealthcare Models International -

94 Students' Perceptions on the Use of Technology in Language Teaching

Journal of Education and Vocational Research Vol. 5, No. 3, pp. 94-100, September 2014 (ISSN 2221-2590) Students’ Perceptions on the use of Technology in Language Teaching *Sandiso Ngcobo, Vukile Mgijima Mangosuthu University of Technology, Durban, South Africa *[email protected] Abstract: Research on the use of technology in educational settings has tended to focus on the impact of technology on the educational outcomes. The other area that that has long been ignored in this research field, when it should form an integral part of research in educational technology, is historical background and views of the students on the technology’s role in achieving educational goals. The research theory that is relevant in this regard is cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT) to additional language learning in education that is drawn from the cultural-historical psychology theory. One-hundred and five participants completed a survey questionnaire. The findings reveal that 66% of the respondents come from families where there are no computers at home and 57% have no good knowledge of computer use even though 53% claim to have been introduced to the use of computers at their last schools. Despite this, the respondents show overwhelming support for the use of technology in higher education. The results are important in that they give hope on the acceptance and possible independent use of technology by students to improve their English proficiency once they have been introduced to technology in language learning. Keywords: historical background, students’ perceptions, additional language learning, technology in education 1. Introduction The use of technology in developing countries’ education systems, such as South Africa where even the distribution of school textbooks can be an issue that is sometimes taken to courts before it materialises, is not yet well explored. -

Nov 2 5 2009

U.S. Department of Homeland Security U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services Ofice ofAdministrative Appeals, MS 2090 Washington, DC 20529-2090 U. S. Citizenship and Immigration NOV 2 5 2009 IN RE: PETITION: Immigrant Petition for Alien Worker as an Alien of Extraordinary Ability Pursuant to Section 203(b)(l)(A) of the Immigration and Nationality Act, 8 U.S.C. 5 1153(b)(l)(A) ON BEHALF OF PETITIONER: INSTRUCTIONS: This is the decision of the Administrative Appeals Office in your case. All documents have been returned to the office that originally decided your case. Any further inquiry must be made to that office. If you believe the law was inappropriately applied or you have additional information that you wish to have considered, you may file a motion to reconsider or a motion to reopen. Please refer to 8 C.F.R. 5 103.5 for the specific requirements. All motions must be submitted to the office that originally decided your case by filing a Form I-290B, Notice of Appeal or Motion, with a fee of $585. Any motion must be filed within 30 days of the decision that the motion seeks to reconsider or reopen, as required by 8 C.F.R. 8 103.5(a)(l)(i). Perry Rhew Chief, Administrative Appeals Office DISCUSSION: The Director, Texas Service Center, initially approved the preference visa petition. Subsequently, the director issued a notice of intent to revoke the approval of the petition (NOIR). In a Notice of Revocation (NOR), the director ultimately revoked the approval of the Immigrant Petition for Alien Worker (Form 1-140). -

Technology and Job-Readiness Blend in South African Higher Education Institute

Technology and Job-Readiness Blend in South African Higher Education Institute Type: Learning Institution Age/Stage: Higher Education CTI Education Group (CTI) is an institute of higher education that serves approximately 11,000 students across 12 campuses in South Africa. The institute consists of two separately registered entities, CTI and Midrand Graduate Institute (MGI), which together, referred to as CTI, focus on arming students with real-life career skills and training them to succeed as employable graduates in a competitive 21st century economy. Because career-readiness is such a steadfast priority for the institute, CTI has developed a number of strategies to ensure that all of its graduates are well prepared for a highly demanding labor market. For example, a virtual employability center will open in 2016 to serve as a resource hub for students looking to enter the job market. The virtual hub will be followed by six physical employability centers to provide personalized, face-to-face job coaching. Finally, employability competencies are firmly embedded into the CTI curriculum, which focuses primarily on information technology, commerce, and law. 1 Intended Outcome: Students progress to employment, post-graduate education, or a professional training program once they graduate from the institution.1 Pearson has gathered student-reported evidence that suggests a majority of students were able to find a job, enroll in post-graduate education, or begin a training program after graduating from one of CTI’s qualifications. More than two-thirds (68 percent) of CTI graduates have reported to be in full-time, part-time or voluntary work; in further education; or in a training program six months after graduating. -

Private Higher Education Institutions

REGISTER OF PRIVATE HIGHER EDUCATION INSTITUTIONS LAST UPDATE 13 DECEMBER 2016 This register of private higher education institutions (hereafter referred to as the Register) is published in accordance with section 54(2)(a)(i) of the Higher Education Act, 1997 (Act No. 101 of 1997) (hereafter referred to as the Act). In terms of section 56(1) (a), any member of the public has the right to inspect the register. IMPORTANT NOTE FOR THE MEDIA The Department of Higher Education and Training recognizes that the information contained in the Register is of public interest and that the media may wish to publish it. In order to avoid misrepresentation in the public domain, the Department of Higher Education and Training kindly requests that all published lists of registered institutions are accompanied by the relevant explanatory information, and include the registered qualifications of each institution. The Register is available for inspection at:http://www.dhet.gov.za: Look under Documents/Registers INTRODUCTION The Register provides the public with information on the registration status of private higher education institutions. Section 54(2)(a)(i) of the Act requires that the Registrar of Private Higher Education Institutions (hereafter referred to as the Registrar) enters the name of the institution in the Register, once an institution is registered. Section 56(1)(b) grants the public the right to view the auditor’s report as issued to the Registrar in terms of section 57(2)(b) of the Act. Copies of registration certificates must be kept as part of the Register, in accordance with Regulation 20.