NSIAD-90-146 Missile Procurement Executive Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prepared by Textore, Inc. Peter Wood, David Yang, and Roger Cliff November 2020

AIR-TO-AIR MISSILES CAPABILITIES AND DEVELOPMENT IN CHINA Prepared by TextOre, Inc. Peter Wood, David Yang, and Roger Cliff November 2020 Printed in the United States of America by the China Aerospace Studies Institute ISBN 9798574996270 To request additional copies, please direct inquiries to Director, China Aerospace Studies Institute, Air University, 55 Lemay Plaza, Montgomery, AL 36112 All photos licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, or under the Fair Use Doctrine under Section 107 of the Copyright Act for nonprofit educational and noncommercial use. All other graphics created by or for China Aerospace Studies Institute Cover art is "J-10 fighter jet takes off for patrol mission," China Military Online 9 October 2018. http://eng.chinamil.com.cn/view/2018-10/09/content_9305984_3.htm E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.airuniversity.af.mil/CASI https://twitter.com/CASI_Research @CASI_Research https://www.facebook.com/CASI.Research.Org https://www.linkedin.com/company/11049011 Disclaimer The views expressed in this academic research paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Government or the Department of Defense. In accordance with Air Force Instruction 51-303, Intellectual Property, Patents, Patent Related Matters, Trademarks and Copyrights; this work is the property of the U.S. Government. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights Reproduction and printing is subject to the Copyright Act of 1976 and applicable treaties of the United States. This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This publication is provided for noncommercial use only. -

Navy Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

Navy Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) Program: Background and Issues for Congress Updated September 30, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL33745 SUMMARY RL33745 Navy Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) September 30, 2021 Program: Background and Issues for Congress Ronald O'Rourke The Aegis ballistic missile defense (BMD) program, which is carried out by the Missile Defense Specialist in Naval Affairs Agency (MDA) and the Navy, gives Navy Aegis cruisers and destroyers a capability for conducting BMD operations. BMD-capable Aegis ships operate in European waters to defend Europe from potential ballistic missile attacks from countries such as Iran, and in in the Western Pacific and the Persian Gulf to provide regional defense against potential ballistic missile attacks from countries such as North Korea and Iran. MDA’s FY2022 budget submission states that “by the end of FY 2022 there will be 48 total BMDS [BMD system] capable ships requiring maintenance support.” The Aegis BMD program is funded mostly through MDA’s budget. The Navy’s budget provides additional funding for BMD-related efforts. MDA’s proposed FY2021 budget requested a total of $1,647.9 million (i.e., about $1.6 billion) in procurement and research and development funding for Aegis BMD efforts, including funding for two Aegis Ashore sites in Poland and Romania. MDA’s budget also includes operations and maintenance (O&M) and military construction (MilCon) funding for the Aegis BMD program. Issues for Congress regarding the Aegis BMD program include the following: whether to approve, reject, or modify MDA’s annual procurement and research and development funding requests for the program; the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the execution of Aegis BMD program efforts; what role, if any, the Aegis BMD program should play in defending the U.S. -

HPCR Manual on International Law Applicable to Air and Missile Warfare

Manual on International Law Applicable to Air and Missile Warfare Bern, 15 May 2009 Program on Humanitarian Policy and Conflict Research at Harvard University © 2009 The President and Fellows of Harvard College ISBN: 978-0-9826701-0-1 No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitt ed in any form without the prior consent of the Program on Humanitarian Policy and Con- fl ict Research at Harvard University. This restriction shall not apply for non-commercial use. A product of extensive consultations, this document was adopted by consensus of an international group of experts on 15 May 2009 in Bern, Switzerland. This document does not necessarily refl ect the views of the Program on Humanitarian Policy and Confl ict Research or of Harvard University. Program on Humanitarian Policy and Confl ict Research Harvard University 1033 Massachusett s Avenue, 4th Floor Cambridge, MA 02138 United States of America Tel.: 617-384-7407 Fax: 617-384-5901 E-mail: [email protected] www.hpcrresearch.org | ii Foreword It is my pleasure and honor to present the HPCR Manual on International Law Applicable to Air and Missile Warfare. This Manual provides the most up-to-date restatement of exist- ing international law applicable to air and missile warfare, as elaborated by an international Group of Experts. As an authoritative restatement, the HPCR Manual contributes to the practical understanding of this important international legal framework. The HPCR Manual is the result of a six-year long endeavor led by the Program on Humanitarian Policy and Confl ict Research at Harvard University (HPCR), during which it convened an international Group of Experts to refl ect on existing rules of international law applicable to air and missile warfare. -

Air-Directed Surface-To-Air Missile Study Methodology

H. T. KAUDERER Air-Directed Surface-to-Air Missile Study Methodology H. Todd Kauderer During June 1995 through September 1998, APL conducted a series of Warfare Analysis Laboratory Exercises (WALEXs) in support of the Naval Air Systems Command. The goal of these exercises was to examine a concept then known as the Air-Directed Surface-to-Air Missile (ADSAM) System in support of Navy Overland Cruise Missile Defense. A team of analysts and engineers from APL and elsewhere was assembled to develop a high-fidelity, physics-based engineering modeling process suitable for understanding and assessing the performance of both individual systems and a “system of systems.” Results of the initial ADSAM Study effort served as the basis for a series of WALEXs involving senior Flag and General Officers and were subsequently presented to the (then) Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Technology. (Keywords: ADSAM, Cruise missiles, Land Attack Cruise Missile Defense, Modeling and simulation, Overland Cruise Missile Defense.) INTRODUCTION In June 1995 the Naval Air Systems Command • Developing an analytical methodology that tied to- (NAVAIR) asked APL to examine the Air-Directed gether a series of previously distinct, “stovepiped” Surface-to-Air Missile (ADSAM) System concept for high-fidelity engineering models into an integrated their Overland Cruise Missile Defense (OCMD) doc- system that allowed the detailed analysis of a “system trine. NAVAIR was concerned that a number of impor- of systems” tant air defense–related decisions were being made -

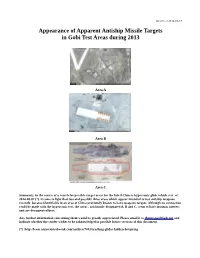

Appearance of Apparent Antiship Missile Targets in Gobi Test Areas During 2013

Version of 2014-09-15 Appearance of Apparent Antiship Missile Targets in Gobi Test Areas during 2013 Area A Area B Area C Summary: In the course of a search for possible target areas for the failed Chinese hypersonic glide vehicle test of 2014-08-07 (*), it came to light that two and possibly three areas which appear intended to test antiship weapons recently became identifiable in an area of China previously known to have weapons targets. Although no connection could be made with the hypersonic test, the areas , arbitrarily designated A, B and C, seem to have intrinsic interest and are documented here. Any further information concerning them would be greatly appreciated. Please email it to [email protected] and indicate whether the sender wishes to be acknowledged in possible future versions of this document. (*) http://lewis.armscontrolwonk.com/archive/7443/crashing-glider-hidden-hotspring Area A 40.466 N, 93.521 E Area A, 2013-11-04 The three shapes at lower left seem clearly meant to represent ships. The dark chevron around them may represent piers. The objects above them and to the right are unidentified, but might represent shore facilities. Warships in Su-ao Harbor, Taiwan The picture scale is almost the same as in the above image of Area A. Both the pair of actual ships at center and the presumed ship targets are about 170 meters long, closely matching the dimensions of Ticonderoga-class cruisers and Kee Lung-class (ex-Kidd) destroyers. Area A, 2013-08-01 Construction of the ship targets is almost complete. -

Missilesmissilesdr Carlo Kopp in the Asia-Pacific

MISSILESMISSILESDr Carlo Kopp in the Asia-Pacific oday, offensive missiles are the primary armament of fighter aircraft, with missile types spanning a wide range of specialised niches in range, speed, guidance technique and intended target. With the Pacific Rim and Indian Ocean regions today the fastest growing area globally in buys of evolved third generation combat aircraft, it is inevitable that this will be reflected in the largest and most diverse inventory of weapons in service. At present the established inventories of weapons are in transition, with a wide variety of Tlegacy types in service, largely acquired during the latter Cold War era, and new technology 4th generation missiles are being widely acquired to supplement or replace existing weapons. The two largest players remain the United States and Russia, although indigenous Israeli, French, German, British and Chinese weapons are well established in specific niches. Air to air missiles, while demanding technologically, are nevertheless affordable to develop and fund from a single national defence budget, and they result in greater diversity than seen previously in larger weapons, or combat aircraft designs. Air-to-air missile types are recognised in three distinct categories: highly agile Within Visual Range (WVR) missiles; less agile but longer ranging Beyond Visual Range (BVR) missiles; and very long range BVR missiles. While the divisions between the latter two categories are less distinct compared against WVR missiles, the longer ranging weapons are often quite unique and usually much larger, to accommodate the required propellant mass. In technological terms, several important developments have been observed over the last decade. -

GAO-21-378, HYPERSONIC WEAPONS: DOD Should Clarify

United States Government Accountability Office Report to Congressional Addressees March 2021 HYPERSONIC WEAPONS DOD Should Clarify Roles and Responsibilities to Ensure Coordination across Development Efforts GAO-21-378 March 2021 HYPERSONIC WEAPONS DOD Should Clarify Roles and Responsibilities to Ensure Coordination across Development Efforts Highlights of GAO-21-378, a report to congressional addressees Why GAO Did This Study What GAO Found Hypersonic missiles, which are an GAO identified 70 efforts to develop hypersonic weapons and related important part of building hypersonic technologies that are estimated to cost almost $15 billion from fiscal years 2015 weapon systems, move at least five through 2024 (see figure). These efforts are widespread across the Department times the speed of sound, have of Defense (DOD) in collaboration with the Department of Energy (DOE) and, in unpredictable flight paths, and are the case of hypersonic technology development, the National Aeronautics and expected to be capable of evading Space Administration (NASA). DOD accounts for nearly all of this amount. today’s defensive systems. DOD has begun multiple efforts to develop Hypersonic Weapon-related and Technology Development Total Reported Funding by Type of offensive hypersonic weapons as well Effort from Fiscal Years 2015 through 2024, in Billions of Then-Year Dollars as technologies to improve its ability to track and defend against them. NASA and DOE are also conducting research into hypersonic technologies. The investments for these efforts are significant. This report identifies: (1) U.S. government efforts to develop hypersonic systems that are underway and their costs, (2) challenges these efforts face and what is being done to address them, and (3) the extent to which the U.S. -

China Missile Chronology

China Missile Chronology Last update: June 2012 2012 18 May 2012 The Department of Defense releases the 2012 “Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China” report. The report highlights that the PLA Air force is modernizing its ground‐based air defense forces with conventional medium‐range ballistic missiles, which can “conduct precision strikes against land targets and naval ships, including aircraft carriers, operating far from China’s shores beyond the first island chain.” According to the Department of Defense’s report, China will acquire DF‐31A intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and enhanced, silo‐based DF‐5 (CSS‐4) ICMBs by 2015. To date, China is the third country that has developed a stealth combat aircraft, after the U.S. and Russia. J‐20 is expected conduct military missions by 2018. It will be equipped with “air‐to‐air missiles, air‐to‐surface missiles, anti‐radiation missiles, laser‐guided bombs and drop bombs.”J‐20 stealth fighter is a distinguished example of Chinese military modernization. – Office of Secretary of Defense, “Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2012,” distributed by U.S. Department of Defense, May 2012, www.defense.gov; Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense, David Helvey, “Press Briefing on 2012 DOD Report to Congress on ‘Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China,’” distributed by U.S. Department of Defense, 18 May 2012, www.defense.gov; “Chengdu J‐20 Multirole Stealth Fighter Aircraft, China,” Airforce‐Technology, www.airforce‐technology.com. 15 April 2012 North Korea shows off a potential new ICBM in a military parade. -

The Future of the U.S. Intercontinental Ballistic Missile Force

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that EDUCATION AND THE ARTS helps improve policy and decisionmaking through ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT research and analysis. HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from INFRASTRUCTURE AND www.rand.org as a public service of the RAND TRANSPORTATION Corporation. INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS NATIONAL SECURITY Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Support RAND Purchase this document TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Browse Reports & Bookstore Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND Project AIR FORCE View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. C O R P O R A T I O N The Future of the U.S. Intercontinental Ballistic Missile Force Lauren Caston, Robert S. -

Air and Missile Defense at a Crossroads New Concepts and Technologies to Defend America’S Overseas Bases

AIR AND MISSILE DEFENSE AT A CROSSROADS NEW CONCEPTS AND TECHNOLOGIES TO DEFEND AMERICA’S OVERSEAS BASES CARL REHBERG MARK GUNZINGER AIR AND MISSILE DEFENSE AT A CROSSROADS NEW CONCEPTS AND TECHNOLOGIES TO DEFEND AMERICA’S OVERSEAS BASES CARL REHBERG AND MARK GUNZINGER 2018 ABOUT THE CENTER FOR STRATEGIC AND BUDGETARY ASSESSMENTS (CSBA) The Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments is an independent, nonpartisan policy research institute established to promote innovative thinking and debate about national security strategy and investment options. CSBA’s analysis focuses on key questions related to existing and emerging threats to U.S. national security, and its goal is to enable policymakers to make informed decisions on matters of strategy, security policy, and resource allocation. ©2018 Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments. All rights reserved. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Carl D. Rehberg is a Non-resident Senior Fellow at the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments. Carl is a retired GS-15, Air Force Colonel and Command Pilot with over 6,200 hours flying time. Carl’s previous job was as Director of the Headquarters Air Force Asia-Pacific Cell, which played a pivotal role in the development of Air Force strategy, force development, planning, analysis and warfighting concepts supporting initiatives related to the Asia-Pacific and the DoD Third Offset Strategy. As Chief, Long-Range Plans of the Air Staff, Carl led the development of future force structure plans and courses of action for numerous Air Force and defense resource and tradespace analyses. In the late 1990s, he served in the Pentagon as a strategic planner, programmer, and analyst, leading several studies for the Secretary of Defense on the Total Force. -

The Missile Defense “Arms Race” Myth

STRATEGIC STUDIES QUARTERLY - POLICY FORUM The Missile Defense “Arms Race” Myth US policy toward ballistic missile defense (BMD) of the homeland is designed to stay ahead of the rogue state threat while relying on nuclear deterrence to prevent an attack from the nuclear missile arsenals of Russia or China. Today, the United States has 44 ground-based interceptors (GBI) and plans to increase the total number of its most capable interceptors to 64 by 2030 with the deployment of the Next Generation Interceptor. After its recent successful test against an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM)-type threat, the United States is also examining how the Standard Missile-3 (SM-3) Block IIA could complement GBIs in a layered home- land missile defense architecture. Domestic critics of US homeland missile defense, as well as Russia and China, claim that increased US missile defense capacity and capability will lead to an arms race. They assert that it will stimulate Russia and China to build more offensive missiles in response, ultimately making the United States less safe. The critics’ logic also assumes that US restraint in missile defense will obviate Russian and Chinese perceived needs for missile modernization and production. These individuals predict a proto- typical action-reaction dynamic that has little empirical support and de- serves great scrutiny. Russian Reaction to US Missile Defenses roadly speaking, Russia could react in two ways to overcome per- ceived advances in US missile defense: proportionally or dispro- portionately increase the overall number of missiles, launchers, and Breentry vehicles in an attempt to overwhelm US missile defense capacity, or develop specific weapon systems meant to evade US missile defenses. -

Post Cold War Air to Air Missile Evolution

Post Cold War Air to Air Missile evolution Dr Carlo Kopp defence focus THE AIR-TO-AIR MISSILE (AAM) IS THE BACKBONE OF MODERN WEAPON SUITES CARRIED BY FIGHTER AIRCRAFT. THERE HAS BEEN considerable evolution since the first AAMs deployed operationally in the late 1950s, and that evolution continues unabated. The past decade has been especially important, with the shift away from analogue guidance systems to digital, the appearance of Focal Plane Array imaging seekers, the commodification of Gallium Arsenide technology monolithic microwave integrated circuits, and the emergence of solid propellant ramjet engines – all impacting on the capabilities of these missiles. The matter of AAM effectiveness and lethality remains controversial and steeped in as much mythology as fact, as competing players and Services market the virtues of their favoured designs. Little has changed since the early 1960s when guided missile proponents declared that fighter performance was irrelevant in the face of the then new US AIM-9B Sidewinder missile and its UK sibling, the DH Firestreak. But the Vietnam war proved this prediction to be just fantasy. Today we see the same arguments, now peddled by bureaucratic and industry proponents of aerodynamically or stealth-wise underperforming fighters. The most widely used Beyond Visual Range missile in the Western world, the US AIM-120A/ B/C AMRAAM, has achieved a success rate in real combat of around 50 per cent, but this has been against Third World targets without modern countermeasures, modern warning systems, MBDA Meteor. or indeed pilot evasive skills. While test range claims for the latest AIM-120 variants sit around 85 per cent, these involved shots against QF-4 drones, which are not representative in turning target performs a major change in trajectory, which technologies used in the design of missiles, as performance of today’s targets, such as Sukhoi puts it outside of the kinematic envelope while the they reflect the competitive pressures of defeating Flanker fighters.