GAO-21-378, HYPERSONIC WEAPONS: DOD Should Clarify

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prepared by Textore, Inc. Peter Wood, David Yang, and Roger Cliff November 2020

AIR-TO-AIR MISSILES CAPABILITIES AND DEVELOPMENT IN CHINA Prepared by TextOre, Inc. Peter Wood, David Yang, and Roger Cliff November 2020 Printed in the United States of America by the China Aerospace Studies Institute ISBN 9798574996270 To request additional copies, please direct inquiries to Director, China Aerospace Studies Institute, Air University, 55 Lemay Plaza, Montgomery, AL 36112 All photos licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, or under the Fair Use Doctrine under Section 107 of the Copyright Act for nonprofit educational and noncommercial use. All other graphics created by or for China Aerospace Studies Institute Cover art is "J-10 fighter jet takes off for patrol mission," China Military Online 9 October 2018. http://eng.chinamil.com.cn/view/2018-10/09/content_9305984_3.htm E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.airuniversity.af.mil/CASI https://twitter.com/CASI_Research @CASI_Research https://www.facebook.com/CASI.Research.Org https://www.linkedin.com/company/11049011 Disclaimer The views expressed in this academic research paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Government or the Department of Defense. In accordance with Air Force Instruction 51-303, Intellectual Property, Patents, Patent Related Matters, Trademarks and Copyrights; this work is the property of the U.S. Government. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights Reproduction and printing is subject to the Copyright Act of 1976 and applicable treaties of the United States. This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This publication is provided for noncommercial use only. -

Nasa X-15 Program

5 24,132 6 9 NASA X-15 PROGRAM By: T.D. Barnes - NASA Contractor - 1960s NASA contractors for the X-15 program were Bendix Field Engineering followed by Unitec, Inc. The NASA High Range Tracking stations were located at Ely and Beatty Nevada with main control being at Dryden/Edwards AFB in California. Personnel at the tracking stations consisted of a Station Manager, a Technical Advisor, and field engineers for the Mod-2 Radar, Data Transmission System, Communications, Telemetry, and Plant Maintenance/Generators. NASA had a site monitor at each tracking station to monitor our contractor operations. Though supporting flights of the X-15 was their main objective, they also participated in flights of the XB-70, the three Lifting Bodies, experimental Lunar Landing vehicles, and an occasional A-12/YF-12/SR-71 Blackbird flight. On mission days a NASA van picked up each member of the crew at their residence for the 4:20 a.m. trip to the tracking station 18 miles North of Beatty on the Tonopah Highway. Upon arrival each performed preflight calibrations and setup of their various systems. The liftoff of the B-52, with the X-15 tucked beneath its wing, seldom occurred after 9:00 a.m. due to the heat effect of the Mojave Desert making it difficult for the planes to acquire altitude. At approximately 0800 hours two pilots from Dryden would proceed uprange to evaluate the condition of the dry lake beds in the event of an emergency landing of the X-15 (always buzzing our station on the way up and back). -

Preparing for Nuclear War: President Reagan's Program

The Center for Defense Infomliansupports a strong eelens* but opposes e-xces- s~eexpenditures or forces It tetiev~Dial strong social, economic and political structures conifflaute equally w national security and are essential to the strength and welfareof our country - @ 1982 CENTER FOR DEFENSE INFORMATION-WASHINGTON, D.C. 1.S.S.N. #0195-6450 Volume X, Number 8 PREPARING FOR NUCLEAR WAR: PRESIDENT REAGAN'S PROGRAM Defense Monitor in Brief President Reagan and his advisors appear to be preparing the United States for nuclear war with the Soviet Union. President Reagan plans to spend $222 Billion in the next six years in an effort to achieve the capacity to fight and win a nuclear war. The U.S. has about 30,000 nuclear weapons today. The U.S. plans to build 17,000 new nuclear weapons in the next decade. Technological advances in the U.S. and U.S.S.R. and changes in nuclear war planning are major factors in the weapons build-up and make nuclear war more likely. Development of new U.S. nuclear weapons like the MX missile create the impression in the U.S., Europe, and the Soviet Union that the U.S.is buildinga nuclear force todestroy the Soviet nuclear arsenal in a preemptive attack. Some of the U.S. weapons being developed may require the abrogation of existing arms control treaties such as the ABM Treaty and Outer Space Treaty, and make any future agreements to restrain the growth of nuclear weapons more difficult to achieve. Nuclear "superiority" loses its meaning when the U.S. -

Navy Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

Navy Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) Program: Background and Issues for Congress Updated September 30, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL33745 SUMMARY RL33745 Navy Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) September 30, 2021 Program: Background and Issues for Congress Ronald O'Rourke The Aegis ballistic missile defense (BMD) program, which is carried out by the Missile Defense Specialist in Naval Affairs Agency (MDA) and the Navy, gives Navy Aegis cruisers and destroyers a capability for conducting BMD operations. BMD-capable Aegis ships operate in European waters to defend Europe from potential ballistic missile attacks from countries such as Iran, and in in the Western Pacific and the Persian Gulf to provide regional defense against potential ballistic missile attacks from countries such as North Korea and Iran. MDA’s FY2022 budget submission states that “by the end of FY 2022 there will be 48 total BMDS [BMD system] capable ships requiring maintenance support.” The Aegis BMD program is funded mostly through MDA’s budget. The Navy’s budget provides additional funding for BMD-related efforts. MDA’s proposed FY2021 budget requested a total of $1,647.9 million (i.e., about $1.6 billion) in procurement and research and development funding for Aegis BMD efforts, including funding for two Aegis Ashore sites in Poland and Romania. MDA’s budget also includes operations and maintenance (O&M) and military construction (MilCon) funding for the Aegis BMD program. Issues for Congress regarding the Aegis BMD program include the following: whether to approve, reject, or modify MDA’s annual procurement and research and development funding requests for the program; the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the execution of Aegis BMD program efforts; what role, if any, the Aegis BMD program should play in defending the U.S. -

HPCR Manual on International Law Applicable to Air and Missile Warfare

Manual on International Law Applicable to Air and Missile Warfare Bern, 15 May 2009 Program on Humanitarian Policy and Conflict Research at Harvard University © 2009 The President and Fellows of Harvard College ISBN: 978-0-9826701-0-1 No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitt ed in any form without the prior consent of the Program on Humanitarian Policy and Con- fl ict Research at Harvard University. This restriction shall not apply for non-commercial use. A product of extensive consultations, this document was adopted by consensus of an international group of experts on 15 May 2009 in Bern, Switzerland. This document does not necessarily refl ect the views of the Program on Humanitarian Policy and Confl ict Research or of Harvard University. Program on Humanitarian Policy and Confl ict Research Harvard University 1033 Massachusett s Avenue, 4th Floor Cambridge, MA 02138 United States of America Tel.: 617-384-7407 Fax: 617-384-5901 E-mail: [email protected] www.hpcrresearch.org | ii Foreword It is my pleasure and honor to present the HPCR Manual on International Law Applicable to Air and Missile Warfare. This Manual provides the most up-to-date restatement of exist- ing international law applicable to air and missile warfare, as elaborated by an international Group of Experts. As an authoritative restatement, the HPCR Manual contributes to the practical understanding of this important international legal framework. The HPCR Manual is the result of a six-year long endeavor led by the Program on Humanitarian Policy and Confl ict Research at Harvard University (HPCR), during which it convened an international Group of Experts to refl ect on existing rules of international law applicable to air and missile warfare. -

Air-Directed Surface-To-Air Missile Study Methodology

H. T. KAUDERER Air-Directed Surface-to-Air Missile Study Methodology H. Todd Kauderer During June 1995 through September 1998, APL conducted a series of Warfare Analysis Laboratory Exercises (WALEXs) in support of the Naval Air Systems Command. The goal of these exercises was to examine a concept then known as the Air-Directed Surface-to-Air Missile (ADSAM) System in support of Navy Overland Cruise Missile Defense. A team of analysts and engineers from APL and elsewhere was assembled to develop a high-fidelity, physics-based engineering modeling process suitable for understanding and assessing the performance of both individual systems and a “system of systems.” Results of the initial ADSAM Study effort served as the basis for a series of WALEXs involving senior Flag and General Officers and were subsequently presented to the (then) Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Technology. (Keywords: ADSAM, Cruise missiles, Land Attack Cruise Missile Defense, Modeling and simulation, Overland Cruise Missile Defense.) INTRODUCTION In June 1995 the Naval Air Systems Command • Developing an analytical methodology that tied to- (NAVAIR) asked APL to examine the Air-Directed gether a series of previously distinct, “stovepiped” Surface-to-Air Missile (ADSAM) System concept for high-fidelity engineering models into an integrated their Overland Cruise Missile Defense (OCMD) doc- system that allowed the detailed analysis of a “system trine. NAVAIR was concerned that a number of impor- of systems” tant air defense–related decisions were being made -

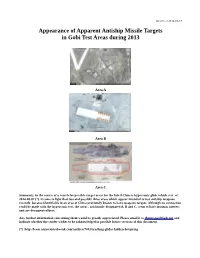

Appearance of Apparent Antiship Missile Targets in Gobi Test Areas During 2013

Version of 2014-09-15 Appearance of Apparent Antiship Missile Targets in Gobi Test Areas during 2013 Area A Area B Area C Summary: In the course of a search for possible target areas for the failed Chinese hypersonic glide vehicle test of 2014-08-07 (*), it came to light that two and possibly three areas which appear intended to test antiship weapons recently became identifiable in an area of China previously known to have weapons targets. Although no connection could be made with the hypersonic test, the areas , arbitrarily designated A, B and C, seem to have intrinsic interest and are documented here. Any further information concerning them would be greatly appreciated. Please email it to [email protected] and indicate whether the sender wishes to be acknowledged in possible future versions of this document. (*) http://lewis.armscontrolwonk.com/archive/7443/crashing-glider-hidden-hotspring Area A 40.466 N, 93.521 E Area A, 2013-11-04 The three shapes at lower left seem clearly meant to represent ships. The dark chevron around them may represent piers. The objects above them and to the right are unidentified, but might represent shore facilities. Warships in Su-ao Harbor, Taiwan The picture scale is almost the same as in the above image of Area A. Both the pair of actual ships at center and the presumed ship targets are about 170 meters long, closely matching the dimensions of Ticonderoga-class cruisers and Kee Lung-class (ex-Kidd) destroyers. Area A, 2013-08-01 Construction of the ship targets is almost complete. -

U.S. Strategic Nuclear Forces: Background, Developments, and Issues

Order Code RL33640 U.S. Strategic Nuclear Forces: Background, Developments, and Issues Updated January 24, 2008 Amy F. Woolf Specialist in National Defense Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division U.S. Strategic Nuclear Forces: Background, Developments, and Issues Summary During the Cold War, the U.S. nuclear arsenal contained many types of delivery vehicles for nuclear weapons. The longer range systems, which included long-range missiles based on U.S. territory, long-range missiles based on submarines, and heavy bombers that could threaten Soviet targets from their bases in the United States, are known as strategic nuclear delivery vehicles. At the end of the Cold War, in 1991, the United States deployed more than 10,000 warheads on these delivery vehicles. That number has declined to around 6,000 warheads today, and is slated, under the 2002 Moscow Treaty, to decline to 2,200 warheads by the year 2012. At the present time, the U.S. land-based ballistic missile force (ICBMs) consists of between 450 and 500 Minuteman III ICBMs, each deployed with between one and three warheads, for a total of 1,200 warheads. The Air Force recently deactivated all 50 of the 10-warhead Peacekeeper ICBMs; it plans to eventually deploy Peacekeeper warheads on some of the Minuteman ICBMs and has begun to deactivate 50 Minuteman III missiles. The Air Force is also modernizing the Minuteman missiles, replacing and upgrading their rocket motors, guidance systems, and other components. The Air Force had expected to begin replacing the Minuteman missiles around 2018, but has decided, instead, to continue to modernize and maintain the existing missiles. -

Conventional Prompt Global Strike (CPGS) Concept Calls for a Strike (CPGS) Capability Would U.S

February 2011 STRATEGIC FORUM National Defense University About the Author Conventional Prompt M. Elaine Bunn is a Distinguished Research Fellow in the Center for Global Strike: Strategic Strategic Research (CSR), Institute for National Strategic Studies, at Asset or Unusable Liability? the National Defense University. Vincent A. Manzo is a Research Analyst in CSR. by M. Elaine Bunn and Vincent A. Manzo Key Points ◆◆ A Conventional Prompt Global he Conventional Prompt Global Strike (CPGS) concept calls for a Strike (CPGS) capability would U.S. capability to deliver conventional strikes anywhere in the world be a valuable strategic asset for some fleeting, denied, and in approximately an hour. The logic of the CPGS concept is straight- difficult-to-reach targets. It would forward. The United States has global security commitments to deter and re- fill a gap in U.S. conventional T strike capability in some plausible spond to a diverse spectrum of threats, ranging from terrorist organizations to high-risk scenarios, contribute to near-peer competitors. The United States might need to strike a time-sensitive a more versatile and credible U.S. target protected by formidable air defenses or located deep inside enemy ter- strategic posture, and potentially enhance deterrence across a di- ritory. Small, high-value targets might pop up without warning in remote or verse spectrum of threats. sensitive areas, potentially precluding the United States from responding to the ◆◆ A small number of CPGS systems situation by employing other conventional weapons systems, deploying Special would not significantly affect the size of the U.S. deployed nuclear Operations Forces (SOF), or relying on the host country. -

A Low-Visibility Force Multiplier Assessing China’S Cruise Missile Ambitions

Gormley, Erickson, and Yuan and Erickson, Gormley, A Low-Visibility Force Multiplier ASSESSING CHINA’s CRUISE MISSILE AMBITIONS Dennis M. Gormley, Andrew S. Erickson, and Jingdong Yuan and Jingdong Yuan Jingdong and S. Erickson, Andrew Dennis M. Gormley, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs The Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs (China Center) was established as an integral part of the National Defense University’s Institute for National Strategic Studies on March 1, 2000, pursuant to Section 914 of the 2000 National Defense Authorization Act. The China Center’s mission is to serve as a national focal point and resource center for multidisciplinary research and analytic exchanges on the national goals and strategic posture of the People’s Republic of China and to focus on China’s ability to develop, field, and deploy an effective military instrument in support of its national strategic objectives. Cover photo: Missile launch from Chinese submarine during China-Russia joint military exercise in eastern China’s Shandong Peninsula. Photo © CHINA NEWSPHOTO/Reuters/Corbis A Low-Visibility Force Multiplier A Low-Visibility Force Multiplier ASSESSING CHINA’s CRUISE MISSILE AMBITIONS Dennis M. Gormley, Andrew S. Erickson, and Jingdong Yuan Published by National Defense University Press for the Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs Institute for National Strategic Studies Washington, D.C. 2014 The ideas expressed in this study are those of the authors alone. They do not represent the policies or estimates of the U.S. Navy or any other organization of the U.S. Government. All the resources referenced are unclassified, predominantly from non-U.S. -

NSIAD-90-146 Missile Procurement Executive Summary

I “1 .” II ..._ -111”1”~1~ . .. - _-.. .- _ _.._.l:rril.tvl-_._._ ._ _.._ _. Slillt3_” _.I .,..- I..-- i;tkrrtkral“1”_.1_.-..-- _..------ Ac~orlnt -.-.----.-..---._._- ing Ol’l’iw.._._..- .-...... I “. ~_I ..-.---------- ---_._--.lll__ .-..” ..” *“I,L,“^I.“m”-““-. .11it\ l’tO0. MISSILE PROCUREMENT Further Production of RAAM Should Not Be Approved Until Questions Are Resolved National Security and International Affairs Division H-22 1734 May 4,199O The Honorable Denny Smith I louse of Representatives Dear Mr. Smith: This report addresses the status of the Advanced Medium Range Air-to-Air Missile (AMRAAM) at the scheduled full-rate production milestone. As requested, we focused on the missile’s demonstrated operational performance, the contractors’ readiness to produce quality missiles at the required rates, and the latest program cost estimates. The report concludes that significant questions about AMRAAM'S performance, reliability, producibility, and affordability remain unresolved. It recommends that the Secretary of Defense not approve any additional AMRAAM production until (1) tests demonstrate that the missile can meet all of its critical performance requirements and that its reliability meets the established requirements, (2) both contractors demonstrate that they can consistently produce quality missiles at the rates required by their contracts, (3) the Air Force and the Navy complete their review of missile quantity requirements, and (4) the Department of Defense determines that the AMRAAM program is affordable within realistic future budget projections and consults with the Congress to ensure that the program complies with the adjusted statutory cost cap. The report also suggests that the Congress deny the $1.34 billion requested for AMRAAM procurement in fiscal year 1991. -

Hypersonic Weapons

HYPERSONIC WEAPONS A Challenge and Opportunity for Strategic Arms Control A Study Prepared on the Recommendation of the Secretary-General’s Advisory Board on Disarmament Matters United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research HYPERSONIC WEAPONS A Challenge and Opportunity for Strategic Arms Control A Study Prepared on the Recommendation of the Secretary-General’s Advisory Board on Disarmament Matters United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research New York, 2019 Note The United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs is publishing this material within the context of General Assembly resolution 73/79 on the United Nations Disarmament Information Programme in order to further an informed debate on topical issues of arms limitation, disarmament and security. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the United Nations or its Member States. Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. These documents are available in the official languages of the United Nations at http://ods.un.org. Specific disarmament- related documents can also be accessed through the disarmament reference collection at www.un.org/disarmament/publications/library. This publication is available from www.un.org/disarmament UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Copyright © United Nations, 2019 All rights reserved Printed at the United Nations, New York Contents Foreword v Summary vii Introduction 1 I. Current state of technology 3 Scope and general characteristics 3 Past and current development programmes 7 United States 7 Russian Federation 10 China 12 India 12 France 13 Japan 13 Possible countermeasures 13 II.