Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles and Their Role in Future Nuclear Forces Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prepared by Textore, Inc. Peter Wood, David Yang, and Roger Cliff November 2020

AIR-TO-AIR MISSILES CAPABILITIES AND DEVELOPMENT IN CHINA Prepared by TextOre, Inc. Peter Wood, David Yang, and Roger Cliff November 2020 Printed in the United States of America by the China Aerospace Studies Institute ISBN 9798574996270 To request additional copies, please direct inquiries to Director, China Aerospace Studies Institute, Air University, 55 Lemay Plaza, Montgomery, AL 36112 All photos licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, or under the Fair Use Doctrine under Section 107 of the Copyright Act for nonprofit educational and noncommercial use. All other graphics created by or for China Aerospace Studies Institute Cover art is "J-10 fighter jet takes off for patrol mission," China Military Online 9 October 2018. http://eng.chinamil.com.cn/view/2018-10/09/content_9305984_3.htm E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.airuniversity.af.mil/CASI https://twitter.com/CASI_Research @CASI_Research https://www.facebook.com/CASI.Research.Org https://www.linkedin.com/company/11049011 Disclaimer The views expressed in this academic research paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Government or the Department of Defense. In accordance with Air Force Instruction 51-303, Intellectual Property, Patents, Patent Related Matters, Trademarks and Copyrights; this work is the property of the U.S. Government. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights Reproduction and printing is subject to the Copyright Act of 1976 and applicable treaties of the United States. This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This publication is provided for noncommercial use only. -

Navy Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) Program: Background and Issues for Congress

Navy Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) Program: Background and Issues for Congress Updated September 30, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL33745 SUMMARY RL33745 Navy Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) September 30, 2021 Program: Background and Issues for Congress Ronald O'Rourke The Aegis ballistic missile defense (BMD) program, which is carried out by the Missile Defense Specialist in Naval Affairs Agency (MDA) and the Navy, gives Navy Aegis cruisers and destroyers a capability for conducting BMD operations. BMD-capable Aegis ships operate in European waters to defend Europe from potential ballistic missile attacks from countries such as Iran, and in in the Western Pacific and the Persian Gulf to provide regional defense against potential ballistic missile attacks from countries such as North Korea and Iran. MDA’s FY2022 budget submission states that “by the end of FY 2022 there will be 48 total BMDS [BMD system] capable ships requiring maintenance support.” The Aegis BMD program is funded mostly through MDA’s budget. The Navy’s budget provides additional funding for BMD-related efforts. MDA’s proposed FY2021 budget requested a total of $1,647.9 million (i.e., about $1.6 billion) in procurement and research and development funding for Aegis BMD efforts, including funding for two Aegis Ashore sites in Poland and Romania. MDA’s budget also includes operations and maintenance (O&M) and military construction (MilCon) funding for the Aegis BMD program. Issues for Congress regarding the Aegis BMD program include the following: whether to approve, reject, or modify MDA’s annual procurement and research and development funding requests for the program; the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the execution of Aegis BMD program efforts; what role, if any, the Aegis BMD program should play in defending the U.S. -

A History of Ballistic Missile Development in the DPRK

Occasional Paper No. 2 A History of Ballistic Missile Development in the DPRK Joseph S. Bermudez Jr. Monitoring Proliferation Threats Project MONTEREY INSTITUTE CENTER FOR NONPROLIFERATION STUDIES OF INTERNATIONAL STUDIES THE CENTER FOR NONPROLIFERATION STUDIES The Center for Nonproliferation Studies (CNS) at the Monterey Institute of International Studies (MIIS) is the largest non-governmental organization in the United States devoted exclusively to research and training on nonproliferation issues. Dr. William C. Potter is the director of CNS, which has a staff of more than 50 full- time personnel and 65 student research assistants, with offices in Monterey, CA; Washington, DC; and Almaty, Kazakhstan. The mission of CNS is to combat the spread of weapons of mass destruction by training the next generation of nonproliferation specialists and disseminating timely information and analysis. For more information on the projects and publications of CNS, contact: Center for Nonproliferation Studies Monterey Institute of International Studies 425 Van Buren Street Monterey, California 93940 USA Tel: 831.647.4154 Fax: 831.647.3519 E-mail: [email protected] Internet Web Site: http://cns.miis.edu CNS Publications Staff Editor Jeffrey W. Knopf Managing Editor Sarah J. Diehl Copyright © Joseph S. Bermudez Jr., 1999. OCCASIONAL PAPERS AVAILABLE FROM CNS: No. 1 Former Soviet Biological Weapons Facilities in Kazakhstan: Past, Present, and Future, by Gulbarshyn Bozheyeva, Yerlan Kunakbayev, and Dastan Yeleukenov, June 1999 No. 2 A History of Ballistic Missile Development in the DPRK, by Joseph S. Bermudez Jr., November 1999 No. 3 Nonproliferation Regimes at Risk, Michael Barletta and Amy Sands, eds., November 1999 Please contact: Managing Editor Center for Nonproliferation Studies Monterey Institute of International Studies 425 Van Buren Street Monterey, California 93940 USA Tel: 831.647.3596 Fax: 831.647.6534 A History of Ballistic Missile Development in the DPRK [Note: Page numbers given do not correctly match pages in this PDF version.] Contents Foreword ii by Timothy V. -

Phillip Saunders Testimony

Testimony before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Hearing on China’s Nucle ar Force s June 10, 2021 Phillip C. Saunders Director, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs Institute of National Strategic Studies, National Defense University The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the National Defense University, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. government. Introduction The People’s Republic of China (PRC) is in the midst of an ambitious strategic modernization that will transform its nuclear arsenal from a limited ground-based nuclear force intended to provide an assured second strike after a nuclear attack into a much larger, technologically advanced, and diverse nuclear triad that will provide PRC leaders with new strategic options. China also fields an increasing number of dual-capable medium and intermediate-range ballistic missiles whose status within a future regional crisis or conflict may be unclear, potentially casting a nuclear shadow over U.S. and allied military operations. In addition to more accurate and more survivable delivery systems, this modernization includes improvements to the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) nuclear command, control, and communications (NC3) and strategic intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) systems that will provide PRC leaders with greater situational awareness in a crisis or conflict. These systems will also support development of ballistic missile defenses (BMD) and enable possible shifts in PRC nuclear -

HPCR Manual on International Law Applicable to Air and Missile Warfare

Manual on International Law Applicable to Air and Missile Warfare Bern, 15 May 2009 Program on Humanitarian Policy and Conflict Research at Harvard University © 2009 The President and Fellows of Harvard College ISBN: 978-0-9826701-0-1 No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitt ed in any form without the prior consent of the Program on Humanitarian Policy and Con- fl ict Research at Harvard University. This restriction shall not apply for non-commercial use. A product of extensive consultations, this document was adopted by consensus of an international group of experts on 15 May 2009 in Bern, Switzerland. This document does not necessarily refl ect the views of the Program on Humanitarian Policy and Confl ict Research or of Harvard University. Program on Humanitarian Policy and Confl ict Research Harvard University 1033 Massachusett s Avenue, 4th Floor Cambridge, MA 02138 United States of America Tel.: 617-384-7407 Fax: 617-384-5901 E-mail: [email protected] www.hpcrresearch.org | ii Foreword It is my pleasure and honor to present the HPCR Manual on International Law Applicable to Air and Missile Warfare. This Manual provides the most up-to-date restatement of exist- ing international law applicable to air and missile warfare, as elaborated by an international Group of Experts. As an authoritative restatement, the HPCR Manual contributes to the practical understanding of this important international legal framework. The HPCR Manual is the result of a six-year long endeavor led by the Program on Humanitarian Policy and Confl ict Research at Harvard University (HPCR), during which it convened an international Group of Experts to refl ect on existing rules of international law applicable to air and missile warfare. -

Explosive Weapon Effectsweapon Overview Effects

CHARACTERISATION OF EXPLOSIVE WEAPONS EXPLOSIVEEXPLOSIVE WEAPON EFFECTSWEAPON OVERVIEW EFFECTS FINAL REPORT ABOUT THE GICHD AND THE PROJECT The Geneva International Centre for Humanitarian Demining (GICHD) is an expert organisation working to reduce the impact of mines, cluster munitions and other explosive hazards, in close partnership with states, the UN and other human security actors. Based at the Maison de la paix in Geneva, the GICHD employs around 55 staff from over 15 countries with unique expertise and knowledge. Our work is made possible by core contributions, project funding and in-kind support from more than 20 governments and organisations. Motivated by its strategic goal to improve human security and equipped with subject expertise in explosive hazards, the GICHD launched a research project to characterise explosive weapons. The GICHD perceives the debate on explosive weapons in populated areas (EWIPA) as an important humanitarian issue. The aim of this research into explosive weapons characteristics and their immediate, destructive effects on humans and structures, is to help inform the ongoing discussions on EWIPA, intended to reduce harm to civilians. The intention of the research is not to discuss the moral, political or legal implications of using explosive weapon systems in populated areas, but to examine their characteristics, effects and use from a technical perspective. The research project started in January 2015 and was guided and advised by a group of 18 international experts dealing with weapons-related research and practitioners who address the implications of explosive weapons in the humanitarian, policy, advocacy and legal fields. This report and its annexes integrate the research efforts of the characterisation of explosive weapons (CEW) project in 2015-2016 and make reference to key information sources in this domain. -

Air-Directed Surface-To-Air Missile Study Methodology

H. T. KAUDERER Air-Directed Surface-to-Air Missile Study Methodology H. Todd Kauderer During June 1995 through September 1998, APL conducted a series of Warfare Analysis Laboratory Exercises (WALEXs) in support of the Naval Air Systems Command. The goal of these exercises was to examine a concept then known as the Air-Directed Surface-to-Air Missile (ADSAM) System in support of Navy Overland Cruise Missile Defense. A team of analysts and engineers from APL and elsewhere was assembled to develop a high-fidelity, physics-based engineering modeling process suitable for understanding and assessing the performance of both individual systems and a “system of systems.” Results of the initial ADSAM Study effort served as the basis for a series of WALEXs involving senior Flag and General Officers and were subsequently presented to the (then) Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Technology. (Keywords: ADSAM, Cruise missiles, Land Attack Cruise Missile Defense, Modeling and simulation, Overland Cruise Missile Defense.) INTRODUCTION In June 1995 the Naval Air Systems Command • Developing an analytical methodology that tied to- (NAVAIR) asked APL to examine the Air-Directed gether a series of previously distinct, “stovepiped” Surface-to-Air Missile (ADSAM) System concept for high-fidelity engineering models into an integrated their Overland Cruise Missile Defense (OCMD) doc- system that allowed the detailed analysis of a “system trine. NAVAIR was concerned that a number of impor- of systems” tant air defense–related decisions were being made -

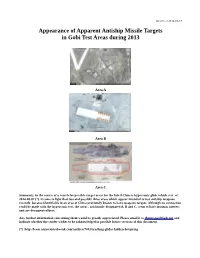

Appearance of Apparent Antiship Missile Targets in Gobi Test Areas During 2013

Version of 2014-09-15 Appearance of Apparent Antiship Missile Targets in Gobi Test Areas during 2013 Area A Area B Area C Summary: In the course of a search for possible target areas for the failed Chinese hypersonic glide vehicle test of 2014-08-07 (*), it came to light that two and possibly three areas which appear intended to test antiship weapons recently became identifiable in an area of China previously known to have weapons targets. Although no connection could be made with the hypersonic test, the areas , arbitrarily designated A, B and C, seem to have intrinsic interest and are documented here. Any further information concerning them would be greatly appreciated. Please email it to [email protected] and indicate whether the sender wishes to be acknowledged in possible future versions of this document. (*) http://lewis.armscontrolwonk.com/archive/7443/crashing-glider-hidden-hotspring Area A 40.466 N, 93.521 E Area A, 2013-11-04 The three shapes at lower left seem clearly meant to represent ships. The dark chevron around them may represent piers. The objects above them and to the right are unidentified, but might represent shore facilities. Warships in Su-ao Harbor, Taiwan The picture scale is almost the same as in the above image of Area A. Both the pair of actual ships at center and the presumed ship targets are about 170 meters long, closely matching the dimensions of Ticonderoga-class cruisers and Kee Lung-class (ex-Kidd) destroyers. Area A, 2013-08-01 Construction of the ship targets is almost complete. -

OSP11: Nuclear Weapons Policy 1967-1998

OPERATIONAL SELECTION POLICY OSP11 NUCLEAR WEAPONS POLICY 1967-1998 Revised November 2005 1 Authority 1.1 The National Archives' Acquisition Policy announced the Archive's intention of developing Operational Selection Policies across government. These would apply the collection themes described in the overall policy to the records of individual departments and agencies. 1.2 Operational Selection Policies are intended to be working tools for those involved in the selection of public records. This policy may therefore be reviewed and revised in the light of comments from users of the records or from archive professionals, the experience of departments in using the policy, or as a result of newly discovered information. There is no formal cycle of review, but comments would be welcomed at any time. The extent of any review or revision exercise will be determined according to the nature of the comments received. If you have any comments upon this policy, please e-mail records- [email protected] or write to: Acquisition and Disposition Policy Manager Records Management Department The National Archives Kew Richmond Surrey TW9 4DU 1.3 Operational Selection Policies do not provide guidance on access to selected records. 2 Scope 2.1 This policy relates to all public records on British nuclear weapons policy and development. The departments and agencies concerned are the Prime Minister’s Office, the Cabinet Office, the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (Security Policy Department, Defence Department, Atomic Energy and Disarmament Department, and Arms Control and Disarmament Department), HM Treasury (Defence and Material Department), the Department of Trade and Industry (Atomic Energy, and Export Control and Non-Proliferation Directorate), the Ministry of Defence (MOD), the Atomic Weapons Establishment (AWE) and the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority (UKAEA). -

NSIAD-90-146 Missile Procurement Executive Summary

I “1 .” II ..._ -111”1”~1~ . .. - _-.. .- _ _.._.l:rril.tvl-_._._ ._ _.._ _. Slillt3_” _.I .,..- I..-- i;tkrrtkral“1”_.1_.-..-- _..------ Ac~orlnt -.-.----.-..---._._- ing Ol’l’iw.._._..- .-...... I “. ~_I ..-.---------- ---_._--.lll__ .-..” ..” *“I,L,“^I.“m”-““-. .11it\ l’tO0. MISSILE PROCUREMENT Further Production of RAAM Should Not Be Approved Until Questions Are Resolved National Security and International Affairs Division H-22 1734 May 4,199O The Honorable Denny Smith I louse of Representatives Dear Mr. Smith: This report addresses the status of the Advanced Medium Range Air-to-Air Missile (AMRAAM) at the scheduled full-rate production milestone. As requested, we focused on the missile’s demonstrated operational performance, the contractors’ readiness to produce quality missiles at the required rates, and the latest program cost estimates. The report concludes that significant questions about AMRAAM'S performance, reliability, producibility, and affordability remain unresolved. It recommends that the Secretary of Defense not approve any additional AMRAAM production until (1) tests demonstrate that the missile can meet all of its critical performance requirements and that its reliability meets the established requirements, (2) both contractors demonstrate that they can consistently produce quality missiles at the rates required by their contracts, (3) the Air Force and the Navy complete their review of missile quantity requirements, and (4) the Department of Defense determines that the AMRAAM program is affordable within realistic future budget projections and consults with the Congress to ensure that the program complies with the adjusted statutory cost cap. The report also suggests that the Congress deny the $1.34 billion requested for AMRAAM procurement in fiscal year 1991. -

NUCLEAR WEAPONS Action Needed to Address the W80-4 Warhead Program’S Schedule Constraints

United States Government Accountability Office Report to Congressional Committees July 2020 NUCLEAR WEAPONS Action Needed to Address the W80-4 Warhead Program's Schedule Constraints GAO-20-409 July 2020 NUCLEAR WEAPONS Action Needed to Address the W80-4 Warhead Program’s Schedule Constraints Highlights of GAO-20-409, a report to congressional committees Why GAO Did This Study What GAO Found To maintain and modernize the U.S. The National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), a separately organized nuclear arsenal, NNSA and DOD agency within the Department of Energy (DOE), has identified a range of risks conduct LEPs. In 2014, they began facing the W80-4 nuclear warhead life extension program (LEP)—including risks an LEP to produce a warhead, the related to developing new technologies and manufacturing processes as well as W80-4, to be carried on the LRSO reestablishing dormant production capabilities. NNSA is managing these risks missile. In February 2019, NNSA using a variety of processes and tools, such as a classified risk database. adopted an FPU delivery date of However, NNSA has introduced potential risk to the program by adopting a date fiscal year 2025 for the W80-4 LEP, (September 2025) for the delivery of the program’s first production unit (FPU) at an estimated cost of about $11.2 that is more than 1 year earlier than the date projected by the program’s own billion over the life of the program. schedule risk analysis process (see figure). NNSA and Department of Defense The explanatory statement (DOD) officials said that they adopted the September 2025 date partly because accompanying the 2018 appropriation the National Defense Authorization Act for fiscal year 2015 specifies that NNSA included a provision for GAO to must deliver the first warhead unit by the end of fiscal year 2025, as well as to review the W80-4 LEP. -

Missilesmissilesdr Carlo Kopp in the Asia-Pacific

MISSILESMISSILESDr Carlo Kopp in the Asia-Pacific oday, offensive missiles are the primary armament of fighter aircraft, with missile types spanning a wide range of specialised niches in range, speed, guidance technique and intended target. With the Pacific Rim and Indian Ocean regions today the fastest growing area globally in buys of evolved third generation combat aircraft, it is inevitable that this will be reflected in the largest and most diverse inventory of weapons in service. At present the established inventories of weapons are in transition, with a wide variety of Tlegacy types in service, largely acquired during the latter Cold War era, and new technology 4th generation missiles are being widely acquired to supplement or replace existing weapons. The two largest players remain the United States and Russia, although indigenous Israeli, French, German, British and Chinese weapons are well established in specific niches. Air to air missiles, while demanding technologically, are nevertheless affordable to develop and fund from a single national defence budget, and they result in greater diversity than seen previously in larger weapons, or combat aircraft designs. Air-to-air missile types are recognised in three distinct categories: highly agile Within Visual Range (WVR) missiles; less agile but longer ranging Beyond Visual Range (BVR) missiles; and very long range BVR missiles. While the divisions between the latter two categories are less distinct compared against WVR missiles, the longer ranging weapons are often quite unique and usually much larger, to accommodate the required propellant mass. In technological terms, several important developments have been observed over the last decade.