Desire and Violence in Protests Against the Iraq War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 110 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 110 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 153 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 6, 2007 No. 22 House of Representatives The House met at 10:30 a.m. and was become true. It is Orwellian double- committee of initial referral has a called to order by the Speaker pro tem- think, an amazing concept. statement that the proposition con- pore (Mr. JOHNSON of Georgia). They believe that if you simply just tains no congressional earmarks. So f say you are lowering drug prices, poof, the chairman of the Appropriations it’s done, ignoring the reality that Committee, Mr. OBEY, conveniently DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO prices really won’t be lowered and submitted to the record on January 29 TEMPORE fewer drugs will be made available to that prior to the omnibus bill being The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- our seniors. considered, quote, ‘‘does not contain fore the House the following commu- They believe that if you just say you any congressional earmarks, limited nication from the Speaker: are implementing all of the 9/11 Com- tax benefits, or limited tariff benefits.’’ WASHINGTON, DC, mission’s recommendations, it changes But, in fact, Mr. Speaker, this omnibus February 6, 2007. the fact that the bill that was passed spending bill that the Democrats I hereby appoint the Honorable HENRY C. here on the floor doesn’t reflect the to- passed last week contained hundreds of ‘‘HANK’’ JOHNSON, Jr. to act as Speaker pro tality of those recommendations. -

House Section

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 109 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 151 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, JUNE 21, 2005 No. 83 House of Representatives The House met at 9 a.m. and was I would like to read an e-mail that there has never been a worse time for called to order by the Speaker pro tem- one of my staffers received at the end Congress to be part of a campaign pore (Miss MCMORRIS). of last week from a friend of hers cur- against public broadcasting. We formed f rently serving in Iraq. The soldier says: the Public Broadcasting Caucus 5 years ‘‘I know there are growing doubts, ago here on Capitol Hill to help pro- DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO questions and concerns by many re- mote the exchange of ideas sur- TEMPORE garding our presence here and how long rounding public broadcasting, to help The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- we should stay. For what it is worth, equip staff and Members of Congress to fore the House the following commu- the attachment hopefully tells you deal with the issues that surround that nication from the Speaker: why we are trying to make a positive important service. difference in this country’s future.’’ There are complexities in areas of le- WASHINGTON, DC, This is the attachment, Madam June 21, 2005. gitimate disagreement and technical I hereby appoint the Honorable CATHY Speaker, and a picture truly is worth matters, make no mistake about it, MCMORRIS to act as Speaker pro tempore on 1,000 words. -

Revisiting Maternalist Frames Across Cases of Women's Mobilization

WSIF-01856; No of Pages 12 Women's Studies International Forum 51 (2015) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Women's Studies International Forum journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/wsif “Resistance is fertile”1: Revisiting maternalist frames across cases of women’s mobilization Michelle E. Carreon a, Valentine M. Moghadam b a American Studies Program, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA b International Affairs Program and Dept. of Sociology, Northeastern University, Boston, MA, USA article info synopsis Available online xxxx Historically, governments and social movements have evoked images of mothers as nurturing, moral, peaceful, or combative agents. But how is a maternalist frame deployed in different contexts? Who deploys this frame, for what purposes and to what ends? In this article, we present a classification scheme to elucidate the diversity and versatility of maternalist frames through the examination of four distinct categories of cases of women's mobilization from the global South as well as North. Drawing on secondary literature and our own ongoing research, we construct a typology of maternalism-from-above and maternalism-from-below to demon- strate how maternalist frames may serve patriarchal or emancipatory purposes with implications for gender justice and the expansion of citizenship rights. © 2015 Published by Elsevier Ltd. In a 1984 photograph, Orlando Valenzuela depicts a smiling appear, and the diverse ways in which maternal identities are Sandinista woman breastfeeding an infant with an AK-47 invoked in political movements and processes, we revisit the strapped to her back. This image – as with previous ones literature and historical record to offer a classification that depicting Vietnamese militant mothers during the U.S. -

Markets Not Capitalism Explores the Gap Between Radically Freed Markets and the Capitalist-Controlled Markets That Prevail Today

individualist anarchism against bosses, inequality, corporate power, and structural poverty Edited by Gary Chartier & Charles W. Johnson Individualist anarchists believe in mutual exchange, not economic privilege. They believe in freed markets, not capitalism. They defend a distinctive response to the challenges of ending global capitalism and achieving social justice: eliminate the political privileges that prop up capitalists. Massive concentrations of wealth, rigid economic hierarchies, and unsustainable modes of production are not the results of the market form, but of markets deformed and rigged by a network of state-secured controls and privileges to the business class. Markets Not Capitalism explores the gap between radically freed markets and the capitalist-controlled markets that prevail today. It explains how liberating market exchange from state capitalist privilege can abolish structural poverty, help working people take control over the conditions of their labor, and redistribute wealth and social power. Featuring discussions of socialism, capitalism, markets, ownership, labor struggle, grassroots privatization, intellectual property, health care, racism, sexism, and environmental issues, this unique collection brings together classic essays by Cleyre, and such contemporary innovators as Kevin Carson and Roderick Long. It introduces an eye-opening approach to radical social thought, rooted equally in libertarian socialism and market anarchism. “We on the left need a good shake to get us thinking, and these arguments for market anarchism do the job in lively and thoughtful fashion.” – Alexander Cockburn, editor and publisher, Counterpunch “Anarchy is not chaos; nor is it violence. This rich and provocative gathering of essays by anarchists past and present imagines society unburdened by state, markets un-warped by capitalism. -

Dear Peace and Justice Activist, July 22, 1997

Peace and Justice Awardees 1995-2006 1995 Mickey and Olivia Abelson They have worked tirelessly through Cambridge Sane Free and others organizations to promote peace on a global basis. They’re incredible! Olivia is a member of Cambridge Community Cable Television and brings programming for the local community. Rosalie Anders Long time member of Cambridge Peace Action and the National board of Women’s Action of New Dedication for (WAND). Committed to creating a better community locally as well as globally, Rosalie has nurtured a housing coop for more than 10 years and devoted loving energy to creating a sustainable Cambridge. Her commitment to peace issues begin with her neighborhood and extend to the international. Michael Bonislawski I hope that his study of labor history and workers’ struggles of the past will lead to some justice… He’s had a life- long experience as a member of labor unions… During his first years at GE, he unrelentingly held to his principles that all workers deserve a safe work place, respect, and decent wages. His dedication to the labor struggle, personally and academically has lasted a life time, and should be recognized for it. Steve Brion-Meisels As a national and State Board member (currently national co-chair) of Peace Action, Steven has devoted his extraordinary ability to lead, design strategies to advance programs using his mediation skills in helping solve problems… Within his neighborhood and for every school in the city, Steven has left his handiwork in the form of peaceable classrooms, middle school mediation programs, commitment to conflict resolution and the ripping effects of boundless caring. -

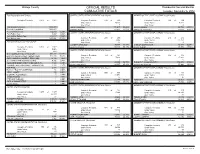

Official Results Cumulative Totals

Orange County OFFICIAL RESULTS Presidential General Election CUMULATIVE TOTALS Tuesday, November 6, 2012 Total Registration and Turnout UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE 45th District MEMBER OF THE STATE ASSEMBLY 55th District Complete Precincts: 1,977 of 1,977 Complete Precincts: 519 of 519 Complete Precincts: 160 of 160 Under Votes: 19,555 Under Votes: 8,377 Over Votes: 7 Over Votes: 4 Total Registered Voters 1,683,001 JOHN CAMPBELL 171,417 58.46% CURT HAGMAN 56,736 65.39% Precinct Registration 1,683,001 SUKHEE KANG 121,814 41.54% GREGG D. FRITCHLE 30,033 34.61% Precinct Ballots Cast 552,018 32.80% UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE 46th District MEMBER OF THE STATE ASSEMBLY 65th District Early Ballots Cast 5,343 0.32% Vote-by-Mail Ballots Cast 575,843 34.22% Total Ballots Cast 1,133,204 67.33% Complete Precincts: 290 of 290 Complete Precincts: 276 of 276 Under Votes: 7,682 Under Votes: 11,167 PRESIDENT AND VICE PRESIDENT Over Votes: 17 Over Votes: 8 LORETTA SANCHEZ 95,694 63.87% SHARON QUIRK-SILVA 68,988 52.04% Complete Precincts: 1,977 of 1,977 JERRY HAYDEN 54,121 36.13% CHRIS NORBY 63,576 47.96% Under Votes: 9,926 UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE 47th District MEMBER OF THE STATE ASSEMBLY 68th District Over Votes: 614 MITT ROMNEY PAUL RYAN (REP) 582,332 51.87% BARACK OBAMA JOSEPH BIDEN (DEM) 512,440 45.65% Complete Precincts: 184 of 184 Complete Precincts: 345 of 345 7,648 17,944 GARY JOHNSON JAMES P. GRAY (LIB) 14,132 1.26% Under Votes: Under Votes: 5 6 JILL STEIN CHERI HONKALA (GRN) 4,792 0.43% Over Votes: Over Votes: 49,599 54.72% 104,706 60.82% ROSEANNE BARR CINDY SHEEHAN (P-F) 3,348 0.30% GARY DELONG DONALD P. -

Speaking from the Heart: Mediation and Sincerity in U.S. Political Speech

Speaking from the Heart: Mediation and Sincerity in U.S. Political Speech David Supp-Montgomerie A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Communication Studies in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2013 Approved by: Christian Lundberg V. William Balthrop Carole Blair Lawrence Grossberg William Keith © 2013 David Supp-Montgomerie ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT David Supp-Montgomerie: Speaking from the Heart: Mediation and Sincerity in U.S. Political Speech (Under the direction of Christian Lundberg) This dissertation is a critique of the idea that the artifice of public speech is a problem to be solved. This idea is shown to entail the privilege attributed to purportedly direct or unmediated speech in U.S. public culture. I propose that we attend to the ēthos producing effects of rhetorical concealment by asserting that all public speech is constituted through rhetorical artifice. Wherever an alternative to rhetoric is offered, one finds a rhetoric of non-rhetoric at work. A primary strategy in such rhetoric is the performance of sincerity. In this dissertation, I analyze the function of sincerity in contexts of public deliberation. I seek to show how claims to sincerity are strategic, demonstrate how claims that a speaker employs artifice have been employed to imply a lack of sincerity, and disabuse communication, rhetoric, and deliberative theory of the notion that sincere expression occurs without technology. In Chapter Two I begin with the original problem of artifice for rhetoric in classical Athens in the writings of Plato and Isocrates. -

The Calhoun-Liberty Journal

LIBERTY COUNTY 50¢ UNOFFICIAL THE CALHOUN-LIBERTY INCLUDES NOV. 6 GENERAL TAX ELECTION RESULTS PRESIDENT AND VICE PRESIDENT Romney, Ryan (REP) .........2298 OURNAL Obama, Biden (DEM) .........0939 CLJNews.comJ WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 7, 2012 Vol. 32, No. 44 Thomas Robert Stevens, Alden Link (OBJ) ...006 Gary Johnson, James P. Gray (LBT) .............009 Virgil H. Goode, Jr., James N. Clymer (CPF) .....003 Jill Stein, Cheri Honkala (GRE) .......................002 Finch elected Liberty County Sheriff; Andre Barnett, Kenneth Cross (REF) ..............000 Stewart Alexander, Alex Mendoza (SOC) ....002 Peta Lindsay, Yari Osori (PSL) ...................000 Roseanne Barr, Cindy Sheehan (PFP) .......016 Calhoun voters put Kimbrel in office Tom Hoefling, Jonathan D. Ellis (AIP) ..........002 Ross C. Anderson, Luis J. Rodriguez (JPF) ..001 There were some close races and anx- ious moments Tuesday night as big UNITED STATES SENATOR Connie Mack (REP).......................1536 changes were made in the sheriff’s of- Bill Nelson (DEM) ........................1584 fice on both sides of the Apalachicola Bill Gaylor (NPA) ............................069 River. Nick Finch, shown at left, was vot- Chris Borgia (NPA) ........................042 ed in as the new Liberty County Sheriff REP. IN CONGRESS after beating incumbent Donnie Conyers DISTRICT 2 by 177 votes. Calhoun County voted in Steve Southerland (REP) ...........2081 retired Blountstown Police Chief Glenn Al Lawson (DEM) ..........................1185 Kimbrel, right, as the new Sheriff. He STATE ATTORNEY -

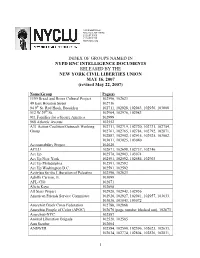

Index of Political Groups Mentioned in the Intelligence Documents

125 Broad Street New York, NY 10004 212.607.3300 212.607.3318 www.nyclu.org INDEX OF GROUPS NAMED IN NYPD RNC INTELLIGENCE DOCUMENTS RELEASED BY THE NEW YORK CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION MAY 16, 2007 (revised May 22, 2007) Name/Group Page(s) 1199 Bread and Roses Cultural Project 102596, 102623 49 East Houston Street 102716 94 9th St. Red Hook, Brooklyn 102711, 102928, 102943, 102956, 103008 512 W 29th St. 102964, 102976, 102983 911 Families for a Secure America 102999 968 Atlantic Avenue 102552 A31 Action Coalition/Outreach Working 102711, 102719, 102720, 102731, 102754, Group 102761, 102765, 102784, 102792, 102871, 102887, 102902, 102915, 102925, 103002, 103011, 103025, 103040 Accountability Project 102620 ACLU 102671, 102698, 102737, 102746 Act Up 102578, 102903, 103074 Act Up New York 102591, 102592, 102684, 102903 Act Up Philadelphia 102591, 102592 Act Up Washington D.C. 102591, 102592 Activists for the Liberation of Palestine 102596, 102623 Adolfo Carrion, Jr. 103099 AFL-CIO 102671 Alicia Keys 102698 All Stars Project 102928, 102943, 102956 American Friends Service Committee 102920, 102927, 102941, 102957, 103033, 103036, 103043, 103072 Anarchist Black Cross Federation 102788, 102868 Anarchist People of Color (APOC) 102670 (page number blacked out), 102673 Anarchist-NYC 102587 Animal Liberation Brigade 102520, 102585 Ann Stauber 102604 ANSWER 102584, 102590, 102596, 102623, 102633, 102634, 102774, 102804, 102826, 102831, 1 102843, 102884, 102900, 102906, 102916, 102919, 102926, 102940, 102952, 102959, 103068, 103076, 103092, 103096 Anthony -

2010-2019 Election Results-Moffat County 2010 Primary Total Reg

2010-2019 Election Results-Moffat County 2010 Primary Total Reg. Voters 2010 General Total Reg. Voters 2011 Coordinated Contest or Question Party Total Cast Votes Contest or Question Party Total Cast Votes Contest or Question US Senator 2730 US Senator 4681 Ken Buck Republican 1339 Ken Buck Republican 3080 Moffat County School District RE #1 Jane Norton Republican 907 Michael F Bennett Democrat 1104 JB Chapman Andrew Romanoff Democrat 131 Bob Kinsley Green 129 Michael F Bennett Democrat 187 Maclyn "Mac" Stringer Libertarian 79 Moffat County School District RE #3 Maclyn "Mac" Stringer Libertarian 1 Charley Miller Unaffiliated 62 Tony St John John Finger Libertarian 1 J Moromisato Unaffiliated 36 Debbie Belleville Representative to 112th US Congress-3 Jason Napolitano Ind Reform 75 Scott R Tipton Republican 1096 Write-in: Bruce E Lohmiller Green 0 Moffat County School District RE #5 Bob McConnell Republican 1043 Write-in: Michele M Newman Unaffiliated 0 Ken Wergin John Salazar Democrat 268 Write-in: Robert Rank Republican 0 Sherry St. Louis Governor Representative to 112th US Congress-3 Dan Maes Republican 1161 John Salazar Democrat 1228 Proposition 103 (statutory) Scott McInnis Republican 1123 Scott R Tipton Republican 3127 YES John Hickenlooper Democrat 265 Gregory Gilman Libertarian 129 NO Dan"Kilo" Sallis Libertarian 2 Jake Segrest Unaffiliated 100 Jaimes Brown Libertarian 0 Write-in: John W Hargis Sr Unaffiliated 0 Secretary of State Write-in: James Fritz Unaffiliated 0 Scott Gessler Republican 1779 Governor/ Lieutenant Governor Bernie Buescher Democrat 242 John Hickenlooper/Joseph Garcia Democrat 351 State Treasurer Dan Maes/Tambor Williams Republican 1393 J.J. -

War of Position on Neoliberal Terrain

Interface: a journal for and about social movements Article Volume 5 (2): 377 - 398 (November 2013) Brissette, War of position on neoliberal terrain Waging a war of position on neoliberal terrain: critical reflections on the counter-recruitment movement Emily Brissette Abstract This paper explores the relationship between neoliberalism and the contemporary movement against military recruitment. It focuses on the way that the counter-recruitment movement is constrained by, reproduces, and in some instances challenges the reigning neoliberal common sense. Engaging with the work of Antonio Gramsci on ideological struggle (what he calls a war of position), the paper critically examines three aspects of counter-recruitment discourse for whether or how well they contribute to a war of position against militarism and neoliberalism. While in many instances counter-recruitment discourse is found to be imbricated with neoliberal assumptions, the paper argues that counter-recruitment work around the poverty draft offers a significant challenge, especially if it can be linked to broader struggles of social transformation. For more than thirty years, a number of peace organizations have waged a (mostly) quiet battle against the presence of military recruiters in American public schools. The war in Iraq brought these efforts to greater public awareness and swelled the ranks of counter-recruitment activists, as many came to see counter-recruitment as a way not only to contest but also to interfere directly with the execution of the war—by disrupting the flow of bodies into the military. While some of this disruption took physical form, as in civil disobedience or guerrilla theater to force the (temporary) closure of recruiting offices, much more of it has been discursive, attempting to counter the narratives the military uses to recruit young people. -

Winter 2020-21 Newsletter

Winter 2020-21, volume XXIV, issue 4 VETERANS FOR PEACE NEWS MINNEAPOLIS/ST. PAUL VETERANS FOR PEACE, CHAPTER 27 Veterans For Peace News is published quar- Save Our VA gets national backing, terly by Mpls./St. Paul Veterans For Peace, continues collaboration with unions Chapter 27. Veterans For Peace works to increase awareness of the costs of war, restrain our government from intervening in the internal affairs of other nations, end the arms race, reduce and even- tually eliminate nuclear weapons, seek justice for veterans and victims of war, and abolish war as an instrument of national policy. We pledge to use democratic and non- violent means to achieve our purpose. To subscribe to this newsletter, Save Our VA and the American Federation of Government Employees rally to stop the please call our office: 612-821-9141 privatization of the VA. Pictured above are VFP members Barry Riesch, Tom Dimond, Mike McDonald, Andy Berman, Dave Logsdon, Tom Bauch, Craig Wood and Jeff Roy Or write: and a number of AFGE union members. Photo from Union Advocate. Veterans For Peace Ch. 27 4200 Cedar Ave, S. #7 Minneapolis, MN 55407 by Arlys Herem and Jeff Roy, expand our efforts. Or e-mail: VFP SOVA Action Committee Minnesota The Campaign’s Outreach Sub- [email protected] Committee contacted over 200 past SOVA he Save Our VA (SOVA) and American activists and is working to build a national net- Our website is: TFederation of Government Employees work of local VFP Action Groups. The www.vfpchapter27.org. rally on October 29th at Hiawatha and Hwy.