DONALD BARTHELME and WRITING AS POLITICAL ACT By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stephen F. Austin State University English 463, Elements of Craft

Stephen F. Austin State University English 463, Elements of Craft Professor: Andrew Brininstool Section Number: 090 Office: LAN-256 Classroom: Ferguson 177 Office Hours: Tue: 11-12:30; Wed: 9-2 Meeting: TR 12:30-1:45 Email: [email protected] Phone: 936 468- 5659 “Randomness I love. And I still love just a holler right in the middle of an ongoing narrative. Pain or joy, ecstasy.” - Barry Hannah Overview The purpose of Elements of Craft is to help fiction writers improve their writing by training them to actively engage with texts--to read as a writer, rather than as a reader. In this course, we will be reading and discussing six larger texts (mostly novels) and two packets of shorter texts (mostly short stories), and while we will be discussing all of the elements that make up a piece of narrative art--setting, dialogue, characterization--the main thrust of this particular Elements course is concerned with the examination of perhaps the two most important literary styles of the twentieth and twenty-first century. In one corner, we have Minimalism. Antonin Chekhov (1860-1904) is often considered the father of what we now consider minimalist prose style. Rather than use this space to launch into a theoretical thesis on what Minimalism is and is not (don't worry: we'll be doing plenty of that later), here are a few brief quotes from writers who wrote or have written in this vein: Joan Didion: "I had...a technical intention...to write a novel so elliptical and fast that it would be over before you noticed it, a novel so fast that it would scarcely exist on the page at all....white space. -

Elizabeth Bishop. Selected Poems T.S. Eliot. the Waste Land, Four

20TH-/21ST-CENTURY AMERICAN LITERATURE GRADUATE COMPREHENSIVE EXAMINATION READING LIST SELECTED BY THE GRADUATE FACULTY THE CANDIDATE IS RESPONSIBLE FOR ALL WRITERS AND WORKS FROM LIST A, AT LEAST THREE WRITERS FROM LIST B, AND AT LEAST THREE WRITERS FROM LIST C. LIST A POETRY: Elizabeth Bishop. Selected Poems T.S. Eliot. The Waste Land, Four Quartets Robert Frost. North of Boston, Mountain Interval. Langston Hughes. One of the Following Collections: The Weary Blues, Fine Clothes to the Jew, Shakespeare in Harlem. (Poems in these collections may be pieced together from works in Hughes’ Collected Poems.) Sylvia Plath. Selected Poems Wallace Stevens. “Sunday Morning” and Other Selected Poems PROSE: Ralph Ellison. Invisible Man William Faulkner. As I Lay Dying; Light in August or The Sound and the Fury; “Barn Burning”; “Dry September”; “The Bear” (version in Go Down, Moses) F. Scott Fitzgerald. The Great Gatsby Ernest Hemingway. A Farewell to Arms, In Our Time Zora Neale Hurston. Their Eyes Were Watching God Maxine Hong Kingston. The Woman Warrior Toni Morrison. Beloved and One of the Following: Sula or The Bluest Eye 20th-/21st-Century American Literature 1 Rev. 1 August 2014 Flannery O’Connor. A Good Man Is Hard to Find and Other Stories or Everything That Rises Must Converge. John Steinbeck. The Grapes of Wrath or Of Mice and Men Eudora Welty. A Curtain of Green DRAMA: Susan Glaspell. Trifles Arthur Miller. Death of a Salesman Eugene O’Neill. One of the Following: Long Day’s Journey into Night, The Ice Man Cometh, or Moon for the Misbegotten Tennessee Williams. -

Markets Not Capitalism Explores the Gap Between Radically Freed Markets and the Capitalist-Controlled Markets That Prevail Today

individualist anarchism against bosses, inequality, corporate power, and structural poverty Edited by Gary Chartier & Charles W. Johnson Individualist anarchists believe in mutual exchange, not economic privilege. They believe in freed markets, not capitalism. They defend a distinctive response to the challenges of ending global capitalism and achieving social justice: eliminate the political privileges that prop up capitalists. Massive concentrations of wealth, rigid economic hierarchies, and unsustainable modes of production are not the results of the market form, but of markets deformed and rigged by a network of state-secured controls and privileges to the business class. Markets Not Capitalism explores the gap between radically freed markets and the capitalist-controlled markets that prevail today. It explains how liberating market exchange from state capitalist privilege can abolish structural poverty, help working people take control over the conditions of their labor, and redistribute wealth and social power. Featuring discussions of socialism, capitalism, markets, ownership, labor struggle, grassroots privatization, intellectual property, health care, racism, sexism, and environmental issues, this unique collection brings together classic essays by Cleyre, and such contemporary innovators as Kevin Carson and Roderick Long. It introduces an eye-opening approach to radical social thought, rooted equally in libertarian socialism and market anarchism. “We on the left need a good shake to get us thinking, and these arguments for market anarchism do the job in lively and thoughtful fashion.” – Alexander Cockburn, editor and publisher, Counterpunch “Anarchy is not chaos; nor is it violence. This rich and provocative gathering of essays by anarchists past and present imagines society unburdened by state, markets un-warped by capitalism. -

Thomas Pynchon: a Brief Chronology

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications, UNL Libraries Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln 6-23-2005 Thomas Pynchon: A Brief Chronology Paul Royster University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libraryscience Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Royster, Paul, "Thomas Pynchon: A Brief Chronology" (2005). Faculty Publications, UNL Libraries. 2. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libraryscience/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications, UNL Libraries by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Thomas Pynchon A Brief Chronology 1937 Born Thomas Ruggles Pynchon Jr., May 8, in Glen Cove (Long Is- land), New York. c.1941 Family moves to nearby Oyster Bay, NY. Father, Thomas R. Pyn- chon Sr., is an industrial surveyor, town supervisor, and local Re- publican Party official. Household will include mother, Cathe- rine Frances (Bennett), younger sister Judith (b. 1942), and brother John. Attends local public schools and is frequent contributor and columnist for high school newspaper. 1953 Graduates from Oyster Bay High School (salutatorian). Attends Cornell University on scholarship; studies physics and engineering. Meets fellow student Richard Fariña. 1955 Leaves Cornell to enlist in U.S. Navy, and is stationed for a time in Norfolk, Virginia. Is thought to have served in the Sixth Fleet in the Mediterranean. 1957 Returns to Cornell, majors in English. Attends classes of Vladimir Nabokov and M. -

At the Tolstoy Museum’

UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ REPRESENTATIONS OF LEO TOLSTOY IN DONALD BARTHELME’S ‘AT THE TOLSTOY MUSEUM’ A proseminar paper by Kai Kajander DEPARTMENT OF LANGUAGES 2009 HUMANISTINEN TIEDEKUNTA KIELTEN LAITOS Kai Kajander REPRESENTATIONS OF LEO TOLSTOY IN DONALD BARTHELME’S ‘AT THE TOLSTOY MUSEUM’ Kandidaatintutkielma Englannin kieli Marraskuu 2009 25 sivua + 1 liite Käsillä oleva tutkielma on tulos mielenkiinnosta postmodernistiseksi kutsuttua kirjallisuu- den suuntausta kohtaan. Viimeisen viidenkymmenen vuoden ajan esillä ollutta kokeellista kirjallisuutta on yleisessä diskurssissa määritelty ennen kaikkea sotaisin metaforin. Post- modernistinen fiktio toisin sanoen tuhoaa, purkaa, rikkoo ja haastaa. Tämän kaltaiset ku- vaukset tyypittävät postmodernin kirjallisuuden ennen kaikkea reaktiiviseksi toiminnaksi. Kuitenkin postmoderni fiktio on ilmiönä moniselitteisempi ja laaja-alaisempi kuin yksin- kertaistavat luonnehdinnat antavat ymmärtää. Kandidaatintutkielmassani lähestyin ko. il- miötä tutkimalla yksittäistä, postmoderniksi luonnehdittavaa tekstiä. Amerikkalaiskirjailija Donald Barthelme on yksi postmodernistisen kirjallisuuden pionee- reista. Tämä tutkielma on analyysi hänen vuonna 1970 julkaisemastaan novellista ’At the Tolstoy Museum’. Tekstissä Barthelme parodioi venäläisen klassikkokirjailija Leo Tolstoin kirjallista ja kulttuurista perintöä. Tarkastelemalla Tolstoin representaatioita Barthelmen tekstissä tutkielma kartoitti Barthelmen suhdetta aikaisemman kirjallisuuden perintee- seen. Taustana tutkielmalle toimi joukko aikaisempia -

Dear Friends of the Kelly Writers House, Summertime at KWH Is Typically Dreamy

Dear Friends of the Kelly Writers House, Summertime at KWH is typically dreamy. We renovation of Writers House in 1997, has On pages 12–13 you’ll read about the mull over the coming year and lovingly plan guided the KWH House Committee in an sixteenth year of the Kelly Writers House programs to fill our calendar. Interns settle into organic planning process to develop the Fellows Program, with a focus on the work research and writing projects that sprawl across Kelly Family Annex. Through Harris, we of the Fellows Seminar, a unique course that the summer months. We clean up mailing lists, connected with architects Michael Schade and enables young writers and writer-critics to tidy the Kane-Wallace Kitchen, and restock all Olivia Tarricone, who designed the Annex have sustained contact with authors of great supplies with an eye toward fall. The pace is to integrate seamlessly into the old Tudor- accomplishment. On pages 14–15, you’ll learn leisurely, the projects long and slow. style cottage (no small feat!). A crackerjack about our unparalleled RealArts@Penn project, Summer 2014 is radically different. On May tech team including Zach Carduner (C’13), which connects undergraduates to the business 20, 2014, just after Penn’s graduation (when we Chris Martin, and Steve McLaughlin (C’08) of art and culture beyond the university. Pages celebrated a record number of students at our helped envision the Wexler Studio as a 16–17 detail our outreach efforts, the work we Senior Capstone event), we broke ground on student-friendly digital recording playground, do to find talented young writers and bring the Kelly Family Annex, a two-story addition chock-full of equipment ready for innovative them to Penn. -

The University of Oklahoma Graduate College

THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE THE SHORT WORKS OF DONALD BARTHELME A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY BARBARA LOUISE ROE Norman, Oklahoma 1982 THE SHORT WORKS OF DONALD BARTHELME APPROVED BY - ^ P L x/x/f — W Qa ^ — DISSERTATION COMMITTEE ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My gratitude extends to my friends, colleagues, and family members for supporting my efforts in writing this study. Those who considerately read this work during its tentative progress and helped to shape my ideas to their present form deserve a special thanks. I am particularly indebted to Professor Robert Murray Davis for encouraging my interest in Barthelme's literature, for patiently guiding me through the starts and stops of this project, and, above all, for his scrupulous editing of each chapter. I am also grateful to Farrar, Straus and Giroux for per mission to reproduce parts of Barthelme's collections. For my husband and children, the completion of this work is at once a source of joy, relief, and perhaps wonder. With unflagging devotion, they have cheered and sustained me, even though the task, I am sure, seemed endless. My deepest grati tude, therefore, is to T., T., and T .— a dynamite family. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS................. v Chapter I. INTRODUCTION ................... I II. THE PARODIES: FICTIONAL FORMS IN TRANSITION..................... 12 III. THE INVENTIVE FICTIONS: STRUCTURAL ALTERNATIVES FOR NARRATIVE AR T .................. 57 IV. THE INTERMEDIA COMPOSITIONS: EXTENDING THE PERIMETERS OF PLAY ............................. 112 V. AFTERWORD.........................190 BIBLIOGRAPHY ......................... 195 IV LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Page ILLUSTRATION 1 From Geoffrey Whitney: A Choice of Emblems ............... -

31295019149813.Pdf (6.632Mb)

WHY DO CITIZENS PROTEST IN NEW DEMOCRACIES?: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF PROTEST POTENTIAL IN MEXICO, SOUTH AFRICA, AND SOUTH KOREA by YOUNG-CHOUL KIM, B.S., M.A. A DISSERTATION IN POLITICAL SCIENCE Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Chairperson of the Committee " < • • "• ^ \ Accepted Dean of the Graduate School December, 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT vi LIST OF TABLES viii LIST OF FIGURES ix CHAPTER L INTRODUCTION 1 Organization of the Study and Summary 6 IL THE LITERATURE 9 Unconventional Forms of Political Participation 10 Concept of Unconventional Forms of Political Participation 12 Perspectives of Unconventional Forms of Political Participation 19 Socio-Psychological Perspective 21 Rational Choice Perspective 26 Cultural Change Perspective 30 The Other Perspective 34 Summary 35 m. CASE STUDIES 39 Mexico 40 Historical Background 40 Democratization 42 Summary and Unconventional Forms of Political Participation 44 South Africa 48 Historical Background 48 Democratization 50 Summary and Unconventional Forms of Political Participation 52 South Korea 55 Historical Background 55 Democratization 60 Summary and Unconventional Forms of Political Participation 62 Summary 64 IV. VARIABLES, DATA, AND METHOD 75 Introduction 75 Hypotheses 77 Indicators and Variables 78 The Dependent Variable: Unconventional Forms of Political Participation 78 The Independent Variables 80 Baseline 80 Cognitive Skills 82 Value Changes 83 Dissatisfaction -

New Social Movements"Of the Early Nineteenthcentury CRAIG CALHOUN

"New Social Movements"of the Early NineteenthCentury CRAIG CALHOUN SOMETIMEAFTER I968, analysts and participants began to speak of "new social movements" that worked outside formal institu- tional channels and emphasized lifestyle, ethical, or "identity" concerns ratherthan narrowlyeconomic goals. A variety of ex- amples informed the conceptualization.Alberto Melucci (I988: 247), for instance, cited feminism, the ecology movement or "greens," the peace movement, and the youth movement.Others added the gay movement, the animal rights movement, and the antiabortionand prochoice movements. These movements were allegedly new in issues, tactics, and constituencies. Above all, they were new by contrastto the labor movement,which was the paradigmatic"old" social movement,and to Marxismand social- ism, which assertedthat class was the centralissue in politics and that a single political economic transformationwould solve the whole rangeof social ills. They were new even by comparisonwith conventional liberalism with its assumptionof fixed individual Craig Calhounis Professorof Sociology and History at the Universityof North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Earlierversions of this paper were presentedin 1991 to the Social Science History Association, the Departmentof Sociology at the University of Oslo, and the Programin ComparativeStudy of Social Trans- formationsat the Universityof Michigan. The authoris gratefulfor comments from members of each audience and also for research assistance from Cindy Hahamovitch. Social Science History 17:3 (Fall I993) Copyright? I993 by the Social Science History Association. ccc oi45-5532/93/$I.50. 386 SOCIAL SCIENCE HISTORY identities and interests. The new social movements thus chal- lenged the conventionaldivision of politics into left and right and broadenedthe definitionof politics to includeissues thathad been consideredoutside the domainof political action (Scott 1990). -

Cogjm.Vol-6 Num-2.Pdf (2.183Mb)

THE END OF AMERICA State of —BOOK REVIEW— he End of America: Letter of Warning to an American Patriot (2007, Chelsea Green) is Disunion T a well-researched and informative survey of the attacks on American democracy during the Bush We Vote No NUMBER OF Administration. Best-selling author Naomi Wolf FEDERAL DOLLARS (The Beauty Myth) provides a solid compilation allocated to security for of examples that illustrate a “fascist shift” in our ESTIMATED NUMBER FEBRUARY 2008 VOL. 6 NO. 2 the DNC: OF PEOPLE society today: Rights being trampled on, voices 50,000,000 being silenced, and powers being abused, right that will attend the DNC: 35,000 here in the good old USA. Described by readers NUMBER OF U.S. as a pamphlet in the tradition of Paine’s “Common CITIES Sense,” the book is a very handy summary of AGE where protests or actions that Noam Chomsky MESA STATE HOUSING: the real state of our union in a tight 155 pages. occured on ‘Super The “fascist shift” Wolf refers to, consists wrote his fi rst book on A CLASSIST SYSTEM Tuesday’ including GJ: Anarchism: of ten steps that are universal tools for would-be 6 dictators trying to close down an open society, such 10 as we consider ours to be. Yes, all ten are visible in PERCENT OF PERCENT OF U.S. TV the U.S. today, from arbitrarily detaining citizens, THE AMERICAN to establishing secret prisons and developing STATIONS POPULATION that are owned by paramilitary forces. Wolf addresses each of the that are racial/ethnic ten steps in turn, showing with a multitude of minorities: minorities: 3.15 examples how these and other activities taking 34 place in post-9/11 America have chillingly NUMBER OF MEGA paralleled tactics and policies seen during NUMBER OF the transformations of Italy under Mussolini, MEDIA COMPANIES AMERICANS that control 90% of all Germany under Hitler, and Russia under Stalin, arrested in 2005 for drug among others. -

AMERICAN LITERARY MINIMALISM by ROBERT CHARLES

AMERICAN LITERARY MINIMALISM by ROBERT CHARLES CLARK (Under the Direction of James Nagel) ABSTRACT American Literary Minimalism stands as an important yet misunderstood stylistic movement. It is an extension of aesthetics established by a diverse group of authors active in the late-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that includes Amy Lowell, William Carlos Williams, and Ezra Pound. Works within the tradition reflect several qualities: the prose is “spare” and “clean”; important plot details are often omitted or left out; practitioners tend to excise material during the editing process; and stories tend to be about “common people” as opposed to the powerful and aristocratic. While these descriptors and the many others that have been posited over the years are in some ways helpful, the mode remains poorly defined. The core idea that differentiates American Minimalism from other movements is that prose and poetry should be extremely efficient, allusive, and implicative. The language in this type of fiction tends to be simple and direct. Narrators do not often use ornate adjectives and rarely offer effusive descriptions of scenery or extensive detail about characters’ backgrounds. Because authors tend to use few words, each is invested with a heightened sense of interpretive significance. Allusion and implication by omission are often employed as a means to compensate for limited exposition, to add depth to stories that on the surface may seem superficial or incomplete. Despite being scattered among eleven decades, American Minimalists share a common aesthetic. They were not so much enamored with the idea that “less is more” but that it is possible to write compact prose that still achieves depth of setting, characterization, and plot without including long passages of exposition. -

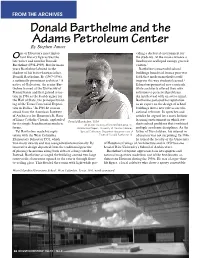

Donald Barthelme and the Adams Petroleum Center

FROM THE ARCHIVES Donald Barthelme and the Adams Petroleum Center By Stephen James ne of Houston’s most impor- viding a sheltered environment for Otant literary figures was the the students. At the main entrance a late writer and novelist Donald flamboyant scalloped canopy greeted Barthelme (1931–1989). But for many visitors.3 years Barthelme labored in the Barthelme’s successful school shadow of his better-known father, buildings benefitted from a post-war Donald Barthelme, Sr. (1907–1996), faith that modern methods could a nationally prominent architect.1 A improve the way students learned.4 native of Galveston, the senior Bar- Educators promoted new curricula thelme trained at the University of while architects offered their own Pennsylvania and first gained atten- solutions to perceived problems. tion in 1936 as the lead designer for An intellectual with an active mind, the Hall of State, the principal build- Barthelme parlayed his reputation ing of the Texas Centennial Exposi- as an expert on the design of school tion in Dallas.2 In 1948 he won an buildings into a new role as an edu- award from the American Institute cational reformer. In speeches and of Architects for Houston’s St. Rose articles he argued for a more holistic of Lima Catholic Church, applauded learning environment in which stu- Donald Barthelme, 1954. for its simple Scandinavian modern All photos courtesy of Donald Barthelme, Sr., dents solved problems that combined forms. Architectural Papers, University of Houston Libraries, multiple academic disciplines. As the Yet Barthelme made his repu- Special Collections Department by permission of father of five children, his interest in tation with the West Columbia Estate of Donald Barthelme, Sr.