PHILOSOPHERS of FIRE I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Akasha (Space) and Shabda (Sound): Vedic and Acoustical Perspectives

1 Akasha (Space) and Shabda (Sound): Vedic and Acoustical perspectives M.G. Prasad Department of Mechanical Engineering Stevens Institute of Technology Hoboken, New Jersey [email protected] Abstract A sequential ordering of five elements on their decreasing subtlety, namely space, air fire, water and earth is stated by Narayanopanishat in Atharva Veda. This statement is examined from an acoustical point of view. The space as an element (bhuta) is qualified by sound as its descriptor (tanmatra). The relation between space and sound and their subtle nature in reference to senses of perception will be presented. The placement of space as the first element and sound as its only property will be discussed in a scientific perspective. Introduction The five elements and their properties are referred to in various places in the Vedic literature. An element is the substance (dravya) which has an associated property (of qualities) termed as guna. The substance-property (or dravya- guna) relationship is very important in dealing with human perception and its nature through the five senses. Several Upanishads and the darshana shastras have dealt with the topic of substance-property (see list of references at the end). The sequential ordering of the five elements is a fundamental issue when dealing with the role of five elements and their properties in the cosmological evolution of the universe. At the same time the order of the properties of elements is also fundamental issue when dealing with the perception of elements is also a through five senses. This paper focuses attention on the element-property (or dravya-guna) relation in reference to space as the element and sound as its property. -

Alchemical Culture and Poetry in Early Modern England

Alchemical culture and poetry in early modern England PHILIP BALL Nature, 4–6 Crinan Street, London N1 9XW, UK There is a longstanding tradition of using alchemical imagery in poetry. It first flourished at the end of the sixteenth century, when the status of alchemy itself was revitalised in European society. Here I explain the reasons for this resurgence of the Hermetic arts, and explore how it was manifested in English culture and in particular in the literary and poetic works of the time. In 1652 the English scholar Elias Ashmole published a collection of alchemical texts called Theatrum Chymicum Britannicum, comprising ‘Several Poeticall Pieces of Our Most Famous English Philosophers’. Among the ‘chemical philosophers’ represented in the volume were the fifteenth-century alchemists Sir George Ripley and Thomas Norton – savants who, Ashmole complained, were renowned on the European continent but unduly neglected in their native country. Ashmole trained in law, but through his (second) marriage to a rich widow twenty years his senior he acquired the private means to indulge at his leisure a scholarly passion for alchemy and astrology. A Royalist by inclination, he had been forced to leave his London home during the English Civil War and had taken refuge in Oxford, the stronghold of Charles I’s forces. In 1677 he donated his impressive collection of antiquities to the University of Oxford, and the building constructed to house them became the Ashmolean, the first public museum in England. Ashmole returned to London after the civil war and began to compile the Theatrum, which was intended initially as a two-volume work. -

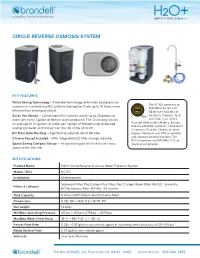

Circle Reverse Osmosis System

CIRCLE REVERSE OSMOSIS SYSTEM KEY FEATURES Water Saving Technology – Patented technology eliminates backpressure The RC100 conforms to common in conventional RO systems making the Circle up to 10 times more NSF/ANSI 42, 53 and efficient than existing products. 58 for the reduction of Saves You Money – Conventional RO systems waste up to 24 gallons of Aesthetic Chlorine, Taste water per every 1 gallon of filtered water produced. The Circle only wastes and Odor, Cyst, VOCs, an average of 2.1 gallons of water per 1 gallon of filtered water produced, Fluoride, Pentavalent Arsenic, Barium, Radium 226/228, Cadmium, Hexavalent saving you water and money over the life of the product!. Chromium, Trivalent Chromium, Lead, RO Filter Auto Flushing – Significantly extends life of RO filter. Copper, Selenium and TDS as verified Chrome Faucet Included – With integrated LED filter change indicator. and substantiated by test data. The RC100 conforms to NSF/ANSI 372 for Space Saving Compact Design – Integrated rapid refill tank means more low lead compliance. space under the sink. SPECIFICATIONS Product Name H2O+ Circle Reverse Osmosis Water Filtration System Model / SKU RC100 Installation Undercounter Sediment Filter, Pre-Carbon Plus Filter, Post Carbon Block Filter (RF-20): 6 months Filters & Lifespan RO Membrane Filter (RF-40): 24 months Tank Capacity 6 Liters (refills fully in less than one hour) Dimensions 9.25” (W) x 16.5” (H) x 13.75” (D) Net weight 14.6 lbs Min/Max Operating Pressure 40 psi – 120 psi (275Kpa – 827Kpa) Min/Max Water Feed Temp 41º F – 95º F (5º C – 35º C) Faucet Flow Rate 0.26 – 0.37 gallons per minute (gpm) at incoming water pressure of 20–100 psi Rated Service Flow 0.07 gallons per minute (gpm) Warranty One Year Warranty PO Box 470085, San Francisco CA, 94147–0085 brondell.com 888-542-3355. -

Bull. Hist. Chem. 13- 14 (1992-93)

ll. t. Ch. 13 - 14 (2 2 tr nnd p t Ar n lt nftr, vd lfr, th trdtnl prnpl f ltn r ldf qd nn ft n pr plnr nd fx vlttn, tn, rprntn "ttr." S " xt Alh", rfrn prnd fr t rrptn." , pp. 66, 886. 25. Ibid., p. 68: "... prpr & xt lnd n pr 4. W. n, "tn Clavis Str Key," Isis,1987, tll t n ..." 78, 644. 26. W. n, The "Summa perfectionis" of pseudo-Geber, 46. hllth, Introitus apertus, BCC, II, 66, "... lphr xtr dn, , pp. 42. n ..." 2. l, "tn Alht," rfrn , pp. 224. 4. frn 4, pp. 24. 28. [Ern hllth,] Sir George Ripley's Epistle to King 48. bb, Foundations , rfrn , p. 28. Edward Unfolded, MS. Gl Unvrt, rn 8, pp. 80, 4. l, " xt Alh", rfrn , p. 64. p. 0. bb, Foundations, rfrn , pp. 22222. 2. MS. rn 8, p. Cf. l Philalethes,Introitusapertus, . Wtfll, Never at Rest, rfrn 8, p. 8. in Bibliotheca chemica curiosa, n Mnt, rfrn 2, l. II, p. 2. r t ll b fl t v bth tn prphr 664. (Cbrd Unvrt brr, Kn MS. 0, f. 22r nd th 30. Ibid., MS. rn 8, pp. 2. rnl (hllth, Introitus apertus, in Bibliotheca chemica curi- 31. Ibid. osa, l. II, p. 66: 32. Ibid., pp. 6. Newton: h t trr prptr ltn , t 33. Ibid. nrl trx prptr nrl n p ltntr, t 4. l, "tn Alht," rfrn , p. 20. tn r vltl, t l [lphr] n tr rvlvntr . [Ern hllth,] Sir George Riplye' s Epistle to King ntnt n ntr , d ntr tt t & trrn d Edward Unfolded, n Chymical, Medicinal, and Chyrurgical AD- prf llnt. -

Sedimentation and Clarification Sedimentation Is the Next Step in Conventional Filtration Plants

Sedimentation and Clarification Sedimentation is the next step in conventional filtration plants. (Direct filtration plants omit this step.) The purpose of sedimentation is to enhance the filtration process by removing particulates. Sedimentation is the process by which suspended particles are removed from the water by means of gravity or separation. In the sedimentation process, the water passes through a relatively quiet and still basin. In these conditions, the floc particles settle to the bottom of the basin, while “clear” water passes out of the basin over an effluent baffle or weir. Figure 7-5 illustrates a typical rectangular sedimentation basin. The solids collect on the basin bottom and are removed by a mechanical “sludge collection” device. As shown in Figure 7-6, the sludge collection device scrapes the solids (sludge) to a collection point within the basin from which it is pumped to disposal or to a sludge treatment process. Sedimentation involves one or more basins, called “clarifiers.” Clarifiers are relatively large open tanks that are either circular or rectangular in shape. In properly designed clarifiers, the velocity of the water is reduced so that gravity is the predominant force acting on the water/solids suspension. The key factor in this process is speed. The rate at which a floc particle drops out of the water has to be faster than the rate at which the water flows from the tank’s inlet or slow mix end to its outlet or filtration end. The difference in specific gravity between the water and the particles causes the particles to settle to the bottom of the basin. -

Yin-Yang, the Five Phases (Wu-Xing), and the Yijing 陰陽 / 五行 / 易經

Yin-yang, the Five Phases (wu-xing), and the Yijing 陰陽 / 五行 / 易經 In the Yijing, yang is represented by a solid line ( ) and yin by a broken line ( ); these are called the "Two Modes" (liang yi 兩義). The figure above depicts the yin-yang cycle mapped as a day. This can be divided into four stages, each corresponding to one of the "Four Images" (si xiang 四象) of the Yijing: 1. young yang (in this case midnight to 6 a.m.): unchanging yang 2. mature yang (6 a.m. to noon): changing yang 3. young yin (noon to 6 p.m.): unchanging yin 4. mature yin (6 p.m. to midnight): changing yin These four stages of changes in turn correspond to four of the Five Phases (wu xing), with the fifth one (earth) corresponding to the perfect balance of yin and yang: | yang | yin | | fire | water | Mature| |earth | | | wood | metal | Young | | | Combining the above two patterns yields the "generating cycle" (below left) of the Five Phases: Combining yin and yang in three-line diagrams yields the "Eight Trigrams" (ba gua 八卦) of the Yijing: Qian Dui Li Zhen Sun Kan Gen Kun (Heaven) (Lake) (Fire) (Thunder) (Wind) (Water) (Mountain) (Earth) 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 The Eight Trigrams can also be mapped against the yin-yang cycle, represented below as the famous Taiji (Supreme Polarity) Diagram (taijitu 太極圖): This also reflects a binary numbering system. If the solid (yang) line is assigned the value of 0 and the broken (yin) line is 1, the Eight Trigram can be arranged to represent the numbers 0 through 7. -

Transfer of Islamic Science to the West

Transfer of Islamic Science to the West IMPORTANT NOTICE: Author: Prof. Dr. Ahmed Y. Al-Hassan Chief Editor: Prof. Dr. Mohamed El-Gomati All rights, including copyright, in the content of this document are owned or controlled for these purposes by FSTC Limited. In Production: Savas Konur accessing these web pages, you agree that you may only download the content for your own personal non-commercial use. You are not permitted to copy, broadcast, download, store (in any medium), transmit, show or play in public, adapt or Release Date: December 2006 change in any way the content of this document for any other purpose whatsoever without the prior written permission of FSTC Publication ID: 625 Limited. Material may not be copied, reproduced, republished, Copyright: © FSTC Limited, 2006 downloaded, posted, broadcast or transmitted in any way except for your own personal non-commercial home use. Any other use requires the prior written permission of FSTC Limited. You agree not to adapt, alter or create a derivative work from any of the material contained in this document or use it for any other purpose other than for your personal non-commercial use. FSTC Limited has taken all reasonable care to ensure that pages published in this document and on the MuslimHeritage.com Web Site were accurate at the time of publication or last modification. Web sites are by nature experimental or constantly changing. Hence information published may be for test purposes only, may be out of date, or may be the personal opinion of the author. Readers should always verify information with the appropriate references before relying on it. -

Magnes: Der Magnetstein Und Der Magnetismus in Den Wissenschaften Der Frühen Neuzeit Mittellateinische Studien Und Texte

Magnes: Der Magnetstein und der Magnetismus in den Wissenschaften der Frühen Neuzeit Mittellateinische Studien und Texte Editor Thomas Haye (Zentrum für Mittelalter- und Frühneuzeitforschung, Universität Göttingen) Founding Editor Paul Gerhard Schmidt (†) (Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg) volume 53 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/mits Magnes Der Magnetstein und der Magnetismus in den Wissenschaften der Frühen Neuzeit von Christoph Sander LEIDEN | BOSTON Zugl.: Berlin, Technische Universität, Diss., 2019 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Sander, Christoph, author. Title: Magnes : der Magnetstein und der Magnetismus in den Wissenschaften der Frühen Neuzeit / von Christoph Sander. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, 2020. | Series: Mittellateinische studien und texte, 0076-9754 ; volume 53 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2019053092 (print) | LCCN 2019053093 (ebook) | ISBN 9789004419261 (hardback) | ISBN 9789004419414 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Magnetism–History–16th century. | Magnetism–History–17th century. Classification: LCC QC751 .S26 2020 (print) | LCC QC751 (ebook) | DDC 538.409/031–dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019053092 LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019053093 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. See and download: brill.com/brill‑typeface. ISSN 0076-9754 ISBN 978-90-04-41926-1 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-41941-4 (e-book) Copyright 2020 by Christoph Sander. Published by Koninklijke -

Ethan Allen Hitchcock Soldier—Humanitarian—Scholar Discoverer of the "True Subject'' of the Hermetic Art

Ethan Allen Hitchcock Soldier—Humanitarian—Scholar Discoverer of the "True Subject'' of the Hermetic Art BY I. BERNARD COHEN TN seeking for a subject for this paper, it had seemed to me J- that it might prove valuable to discuss certain aspects of our American culture from the vantage point of my own speciality as historian of science and to illustrate for you the way in which the study of the history of science may provide new emphases in American cultural history—sometimes considerably at variance with established interpretations. American cultural history has, thus far, been written largely with the history of science left out. I shall not go into the reasons for that omission—they are fairly obvious in the light of the youth of the history of science as a serious, independent discipline. This subject enables us to form new ideas about the state of our culture at various periods, it casts light on the effects of American creativity upon Europeans, and it focuses attention on neglected figures whose value is appreciated abroad but not at home. For example, our opinion of American higher education in the early nineteenth century is altered when we discover that at Harvard and elsewhere the amount of required science and mathematics was exactly three times as great as it is today in an "age of science."^ In the eighteenth century when, according to Barrett Wendell, Harvard gave its » See "Harvard and the Scientific Spirit," Harvard Alumni Bull, 7 Feb. 1948. 3O AMERICAN ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY [April, students only "a fair training in Latin -

H67 2018 Dez06 Final

Mitteilungen der Wilhelm-Ostwald-Gesellschaft e.V. 23. Jg. 2018, Heft 2 ISSN 1433-3910 _________________________________________________________________ Inhalt Zur 67. Ausgabe der „Mitteilungen“ .................................................................... 3 Die Harmothek: 2. Std.: Unbunte Harmonien Wilhelm Ostwald ................................................................................. ……. 4 Chemie an der Alma Mater Lipsiensis von den Anfängen bis zum Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts Lothar Beyer ................................................................................................. 9 Studenten und Assistenten jüdischer Herkunft bei Wilhelm Ostwald Ulf Messow .......................................................................… ........................ 36 Aerogele: eine luftige Brücke zwischen Nano- und Makrowelt Christoph Ziegler und Alexander Eychmüller ............................................. 48 Der Forstwissenschaftler Eugen Ostwald - Bruder von Wilhelm Ostwald Ulf Messow .......................................................................… ........................ 55 Corrigendum .. .......................................................................… ............….. ........ 61 Gesellschaftsnachrichten .. ................................................................................... 63 Autorenhinweise................................................................................................... 64 _________________________________________________________________ © Wilhelm-Ostwald-Gesellschaft -

Björk's Biophilia Björk's Whole Career Has Been a Quest for the Ultimate Fusion of the Organic and the Electronic

Björk's Biophilia Björk's whole career has been a quest for the ultimate fusion of the organic and the electronic. With her new project Biophilia – part live show, part album, part iPad app – she might just have got there Michael Cragg The Guardian, Saturday 28 May 2011 larger | smaller Iceland's singer Bjork performs during the Rock en Seine music festival, 26 August 2007 in Saint-Cloud Photograph: Afp/AFP/Getty Images For Björk, technology, nature and art have always been inextricably linked. "In Iceland, everything revolves around nature, 24 hours a day," she told Oor magazine in 1997. "Earthquakes, snowstorms, rain, ice, volcanic eruptions, geysers … very elementary and uncontrollable. But on the other hand, Iceland is incredibly modern; everything is hi- tech." The Modern Things, a track from 1995's Post, playfully posits the theory that technology has always existed, waiting in mountains for humans to catch up. In fact, Björk has always seemed like an artist who's been waiting for technology to catch up with her. Finally, it seems to have done so. When Apple announced details of its iPad early last year, it acted as a catalyst for what would become Biophilia, Björk's seventh and most elaborate album, the title of which means "love of life or living systems". Along with a conventional album release, complete with music videos – at least one of which has been directed by Eternal Sunshine's Michel Gondry – Biophilia will also be released as an "app album" and premiered as a multimedia live extravaganza at MIF. Biophilia for iPad will include around 10 separate apps, all housed within one "mother" app. -

The Image and Identity of the Alchemist in Seventeenth-Century

THE IMAGE AND IDENTITY OF THE ALCHEMIST IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY NETHERLANDISH ART Dana Kelly-Ann Rehn Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the coursework requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Studies in Art History) School of History and Politics University of Adelaide July 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS TITLE PAGE i TABLE OF CONTENTS ii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS iii DECLARATION v ABSTRACT vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS vii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 ALCHEMY: A CONTROVERSIAL PROFESSION, PAST AND PRESENT 7 3 FOOLS AND CHARLATANS 36 4 THE SCHOLAR 68 5 CONCLUSION 95 BIBLIOGRAPHY 103 CATALOGUE 115 ii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS FIGURE 1 Philip Galle (After Pieter Bruegel the Elder), The Alchemist, c.1558 118 FIGURE 2 Adriaen van de Venne, Rijcke-armoede („Rich poverty‟), 1636 119 FIGURE 3 Adriaen van Ostade, Alchemist, 1661 120 FIGURE 4 Cornelis Bega, The Alchemist, 1663 121 FIGURE 5 David Teniers the Younger, The Alchemist, 1649 122 FIGURE 6 David Teniers the Younger, Tavern Scene, 1658 123 FIGURE 7 David Teniers the Younger, Tavern Scene, Detail, 1658 124 FIGURE 8 Jan Steen, The Alchemist, c.1668 125 FIGURE 9 Jan Steen, Title Unknown, 1668 126 FIGURE 10 Hendrik Heerschop, The Alchemist, 1671 128 FIGURE 11 Hendrik Heerschop, The Alchemist's Experiment Takes Fire, 1687 129 FIGURE 12 Frans van Mieris the Elder, An Alchemist and His Assistant in a Workshop, c.1655 130 FIGURE 13 Thomas Wijck, The Alchemist, c.1650 131 FIGURE 14 Pierre François Basan, 1800s, after David Teniers the Younger, Le Plaisir des Fous („The Pleasure of Fools‟), 1610-1690 132 FIGURE 15